View PDF of Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005 Made - - - - 1st February 2005 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Boundary Committee for England(a), acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(b), has submitted to the Electoral Commission(c) recommendations dated October 2004 on its review of the county of Lancashire: And whereas the Electoral Commission have decided to give effect, with modifications, to those recommendations: And whereas a period of not less than six weeks has expired since the receipt of those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Electoral Commission, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by sections 17(d) and 26(e) of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling them in that behalf, hereby make the following Order: Citation and commencement 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005. (2) This Order shall come into force – (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005, on the day after that on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005. Interpretation 2. In this Order – (a) The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, established by the Electoral Commission in accordance with section 14 of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (c.41). The Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (S.I. -

Data Myout Ward Codes Contents Section One

CONTENTS DATA MYOUT SECTION ONE WARD CODES SECTION lWO vS4 ON TM? ICL 2900 Fonrat lqi3q S&m I Title: IAuthor: Irate: Isheet: 1 I ‘lLmm VS4 I OFWUSEC I SKP 1988 I oNMuNEI’Ic TAm I I I CcmwrER TAPE FILE sPEcrFIcATTm ***** ***************************** This pap de9mibee the intent ad fozmatof the megnetictape verelon of table VS4. I All erquiriescOnzermng the contentof the tebleeor arrerqeuents dietrilution”shcmldbe,a~ to: VlTf3L ST/W5TICS cu~I=Q C+L ICES Officeof Fqulation Cenewes an5 Sumeye Tltd.field Hante m15 5RR Tel: TiHield (0329)42511X305J3 ~lf ic emquuaee omcernwg -W ~ my be altermtiwly addresed to: cDstete Grulpu MR5 S ~EwJANE Tel: Titd_field(0329)42511 x342I Accpyof thewholetapewilllx providedbmstcmws. ‘13u6eonly ted in W will receivethe whole tape, ani ehmld mke their mm ~ for extractingthe :zequheddata. The magnetictepe will k in a formatsuitablefor ~ixJ on ICL (1900or 2900 s-e-rise)or H mahfram madbee. Title: IAuthor: Imte: Imeet: 2 { TAmE VS4 I oKs/aslK SEP 1988 I oNMAaa3rIc TAPE / / / ! KGICAL m SIFUCNJRE I The magnetictape v-ion of the tape will be set cat ae if the tables hadhenprapared using the OFCS tahlaticm utilityTAUerdtheta~ had / been writtenueiru the W utiliiwALCZNSAVEwhi~ savesteblee h a format I suitablefor data-intercimge. - This mans that the ffle is @ysically a file of fhed kqth 80 &aracter remzd.emth a logicalhierarchyof: Fm.E !mBL-5 ARE?+ Textuallabelswill be proviW &m to the ame lwel (naxrative daacriptim of the file,table identi~, area mme.s)hz tstubardmlmn labelseni explanatcq w will rxJtbe imll.kid. If ~ hevethe TAUeoftwareamiwiah tiuseit tiperfozm further analyeesof thedata, than they may baabletousethe~ utilitytoreadths dataintotha TAUsys&n. -

West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme

Regional Competitiveness and Employment Objective 2007 – 2013 West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme Version 3 July 2012 CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 – 5 2a SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS - ORIGINAL 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 6 – 14 2.2 Employment 15 – 19 2.3 Competition 20 – 27 2.4 Enterprise 28 – 32 2.5 Innovation 33 – 37 2.6 Investment 38 – 42 2.7 Skills 43 – 47 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 48 – 50 2.9 Rural 51 – 54 2.10 Urban 55 – 58 2.11 Lessons Learnt 59 – 64 2.12 SWOT Analysis 65 – 70 2b SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS – UPDATED 2010 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 71 – 83 2.2 Employment 83 – 87 2.3 Competition 88 – 95 2.4 Enterprise 96 – 100 2.5 Innovation 101 – 105 2.6 Investment 106 – 111 2.7 Skills 112 – 119 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 120 – 122 2.9 Rural 123 – 126 2.10 Urban 127 – 130 2.11 Lessons Learnt 131 – 136 2.12 SWOT Analysis 137 - 142 3 STRATEGY 3.1 Challenges 143 - 145 3.2 Policy Context 145 - 149 3.3 Priorities for Action 150 - 164 3.4 Process for Chosen Strategy 165 3.5 Alignment with the Main Strategies of the West 165 - 166 Midlands 3.6 Development of the West Midlands Economic 166 Strategy 3.7 Strategic Environmental Assessment 166 - 167 3.8 Lisbon Earmarking 167 3.9 Lisbon Agenda and the Lisbon National Reform 167 Programme 3.10 Partnership Involvement 167 3.11 Additionality 167 - 168 4 PRIORITY AXES Priority 1 – Promoting Innovation and Research and Development 4.1 Rationale and Objective 169 - 170 4.2 Description of Activities -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Draft Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Hyndburn in Lancashire

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Hyndburn in Lancashire February 2000 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND The Local Government Commission for England is an independent body set up by Parliament. Our task is to review and make recommendations to the Government on whether there should be changes to the structure of local government, the boundaries of individual local authority areas, and their electoral arrangements. Members of the Commission are: Professor Malcolm Grant (Chairman) Professor Michael Clarke CBE (Deputy Chairman) Peter Brokenshire Kru Desai Pamela Gordon Robin Gray Robert Hughes CBE Barbara Stephens (Chief Executive) We are statutorily required to review periodically the electoral arrangements – such as the number of councillors representing electors in each area and the number and boundaries of wards and electoral divisions – of every principal local authority in England. In broad terms our objective is to ensure that the number of electors represented by each councillor in an area is as nearly as possible the same, taking into account local circumstances. We can recommend changes to ward boundaries, and the number of councillors and ward names. We can also make recommendations for change to the electoral arrangements of parish councils in the borough. This report sets out the Commission’s draft recommendations on the electoral arrangements for the borough of Hyndburn in Lancashire. © Crown Copyright 2000 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Local Government Commission for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. -

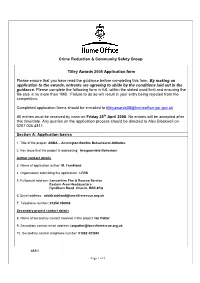

Crime Reduction & Community Safety Group Tilley Awards 2008 Application Form Please Ensure That You Have Read the Guidance B

Crime Reduction & Community Safety Group Tilley Awards 2008 Application form Please ensure that you have read the guidance before completing this form. By making an application to the awards, entrants are agreeing to abide by the conditions laid out in the guidance. Please complete the following form in full, within the stated word limit and ensuring the file size is no more than 1MB. Failure to do so will result in your entry being rejected from the competition. Completed application forms should be e-mailed to [email protected]. All entries must be received by noon on Friday 25th April 2008. No entries will be accepted after this time/date. Any queries on the application process should be directed to Alex Blackwell on 0207 035 4811. Section A: Application basics 1. Title of the project: ABBA – Accrington Bonfire Behavioural Attitudes 2. Key issue that the project is addressing: Irresponsible Behaviour Author contact details 3. Name of application author: M. Frankland 4. Organisation submitting the application: LFRS 5. Full postal address: Lancashire Fire & Rescue Service Eastern Area Headquarters Hyndburn Road, Church, BB5 4EQ 6. Email address: [email protected] 7. Telephone number: 01254 356988 Secondary project contact details 8. Name of secondary contact involved in the project: Ian Potter 9. Secondary contact email address: [email protected] 10. Secondary contact telephone number: 01282 423240 ABBA Page 1 of 3 Endorsing representative contact details 11. Name of endorsing senior representative from lead Organisation: AM Aspden 12. Endorsing representative’s email address: [email protected] 13. For all entries from England & Wales please state which Government Office or Welsh Assembly Government your organisation is covered by e.g. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No. 67 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND RETORT NO. b"7 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Sir Edmund Compton, GCB.KBE. DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J M Rankin,QC. MEMBERS The Countess Of Albemarle, DBE. Mr 0? C Benfield. Professor Michael Chisholm. Sir Andrew Wheatley,CBE. Mr P B Young, CBE. PH To the Rt Hon Roy. Jenkins MF Secretary of State for the Home -Department PROPOSALS FOR REVISED ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE BOROUGH OF HYNDBURN IN THE COUNTY OF LANCASHIRE 1. We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for the borough of Hyndburn in accordance with the requirements of section 63 and Schedule 9 to the Local Government Act 1972, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements for that borough. 2. In accordance with the procedure laid down in section 60 (1) and (2) of the 1972 Act, notice was given on 13 May 197^ that we were to undertake this review. This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to the Kyndburn Borough Council, copies of which were circulated to the Lancashire County Council, the Altham Parish Council, the Members of Parliament for the constituencies concerned and the headquarters of the main political parties,. Copies v/ere also sent to the editors of the local newspapers circulating ir. the area and.to the local government press. Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from any interested bodies. -

Notice of Elections Agents HBC May 2021

NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS' NAMES AND OFFICES Hyndburn Borough Council Election of a Borough Councillor for Altham on Thursday 6 May 21 I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them may be sent, have respectively been declared in writing to me as follows: Name of Correspondence Name of Election Agent Address Candidate MOLINEUX 10 Mill Gardens, Great Harwood, ALLEN Gareth Jason BB6 7FN Dominik Sean JONES 45 Warmden Avenue, Accrington, BUTTON Graham Lancashire, BB5 2PR Stephen Dated 08/04/2021 Jane Ellis Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Scaitcliffe House, Ormerod Street, Accrington, Lancashire, BB5 0PF NOTICE OF ELECTION AGENTS' NAMES AND OFFICES Hyndburn Borough Council Election of a Borough Councillor for Barnfield on Thursday 6 May 21 I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the names of election agents of the candidates at this election, and the addresses of the offices or places of such election agents to which all claims, notices, writs, summons, and other documents addressed to them may be sent, have respectively been declared in writing to me as follows: Name of Correspondence Name of Election Agent Address Candidate HURN 64 Oakwood Road, Accrington, CASSIDY Terry BB5 2PG Daniel PLUMMER 170 Bold Street, Accrington, MONTAGUE Joyce N Lancashire, BB5 6SR Caroline Elizabeth Dated 08/04/2021 Jane Ellis Returning Officer Printed -

2001 No. 2469 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2001 No. 2469 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Borough of Hyndburn (Electoral Changes) Order 2001 Made ----- 3rdJuly 2001 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated September 2000 on its review of the borough(b) of Hyndburn together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(c) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Borough of Hyndburn (Electoral Changes) Order 2001. (2) This Order shall come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 2nd May 2002, on 15th October 2001; (b) for all other purposes, on 2nd May 2002. (3) In this Order— “borough” means the borough of Hyndburn; “existing”, in relation to a ward, means the ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; and any reference to the map is a reference to the map prepared by the Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions marked “Map of the Borough of Hyndburn (Electoral Changes) Order 2001”, and deposited in accordance with regulation 27 of the Local Government Changes for England Regulations 1994(d). -

Hyndburn Borough Council Election Results 1973-2012

Hyndburn Borough Council Election Results 1973-2012 Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher The Elections Centre Plymouth University The information contained in this report has been obtained from a number of sources. Election results from the immediate post-reorganisation period were painstakingly collected by Alan Willis largely, although not exclusively, from local newspaper reports. From the mid- 1980s onwards the results have been obtained from each local authority by the Elections Centre. The data are stored in a database designed by Lawrence Ware and maintained by Brian Cheal and others at Plymouth University. Despite our best efforts some information remains elusive whilst we accept that some errors are likely to remain. Notice of any mistakes should be sent to [email protected]. The results sequence can be kept up to date by purchasing copies of the annual Local Elections Handbook, details of which can be obtained by contacting the email address above. Front cover: the graph shows the distribution of percentage vote shares over the period covered by the results. The lines reflect the colours traditionally used by the three main parties. The grey line is the share obtained by Independent candidates while the purple line groups together the vote shares for all other parties. Rear cover: the top graph shows the percentage share of council seats for the main parties as well as those won by Independents and other parties. The lines take account of any by- election changes (but not those resulting from elected councillors switching party allegiance) as well as the transfers of seats during the main round of local election. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Review

DECISION RIBBLE VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL REPORT TO POLICY AND FINANCE COMMITTEE Agenda Item No. meeting date: 24th JANUARY 2017 title: LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REVIEW – WARDING PROPOSALS submitted by: DIRECTOR OF RESOURCES principal author: MICHELLE HAWORTH – PRINCIPAL POLICY AND PERFORMANCE OFFICER 1 PURPOSE 1.1 The 2nd stage of the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s review of Ribble Valley is to respond to the consultation and put forward warding proposals. This report seeks approval for the proposals below. 1.2 Relevance to the Council’s ambitions and priorities: • Community Objectives – A main consideration for Council size is our Governance and • Corporate Priorities – decision making arrangements. Retaining 40 Councillors provides efficient and effective representation to the public. • Other Considerations - The distribution of the 40 Councillors has been considered - ensuring electoral equality and community representation. 2 BACKGROUND 2.1 The Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) confirmed, following its meeting on 15th November, that they agreed with the Council’s size submission - this being 40 elected members. They also advised that there was some flexibility if, when the Council looked at making its proposals, the Council felt that more or less Councillors would be a better reflection of communities (indicating between 38- 42 would be acceptable). 2.2 The LGBCE launched the consultation process on 22nd November and this runs until 30th January. The consultation can be found at - https://www.lgbce.org.uk/current- reviews/north-west/lancashire/ribble-valley 2.3 In order to meet the Commission’s submission deadline for our warding proposals, the proposals need to be agreed by this committee. -

Regional Identity in Late Nineteenth-Century England; Discursive Terrains and Rhetorical Strategies

International Journal of Regional and Local History ISSN: 2051-4530 (Print) 2051-4549 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yjrl20 Regional identity in late nineteenth-century England; discursive terrains and rhetorical strategies Bernard Deacon To cite this article: Bernard Deacon (2016) Regional identity in late nineteenth-century England; discursive terrains and rhetorical strategies, International Journal of Regional and Local History, 11:2, 59-74, DOI: 10.1080/20514530.2016.1252513 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20514530.2016.1252513 Published online: 16 Nov 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yjrl20 Download by: [University of Exeter] Date: 04 December 2016, At: 01:37 international journal of regional and local history, Vol. 11 No. 2, November, 2016, 59–74 Regional identity in late nineteenth- century England; discursive terrains and rhetorical strategies Bernard Deacon Institute of Cornish Studies, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Exeter, Cornwall Campus, Tremough, Penryn, UK Regional identity and regionalist politics in contemporary England seem muted and indistinct when compared with some other European regions. It is therefore unsurprising that historians have failed to discover unambiguous regional identities in the past. However, this article investigates one possible exception in a case study of a peripheral English region. Adopting concepts of narrative, discourse and rhetoric, it examines the discursive moments and rhe- torical strategies of spatial identity in nineteenth-century Cornwall. Evidence of a tentative regionalism is marshalled in order to reflect on the usefulness of social scientific approaches to discourse and rhetoric for understanding a specific place identity of late nineteenth-century England.