Virtual Dakota County Planning Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community Testimony in Response to the Department of Army

OFFICERS Shakopee Mdewakanton Charlie Vig Chairman Sioux Community Keith B. Anderson 2330 SIOUX TRAIL NW • PRIOR LAKE, MINNESOTA Vice Chairman TRIBAL OFFICE: 952-445-8900 • FAX: 952-445-8906 Freedom Brewer Secretary/Treasurer Testimony in Response to the Department of Army, Department of Interior, and Department of Justice’s Tribal Consultation on Infrastructure Development Projects November 15, 2016 Federal Agency Consultation Prior Lake, MN The Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community (“SMSC” or “Tribe”) is a federally-recognized tribal government, located in Prior Lake, Minnesota. In recent decades, there has been a steady march of economic development toward our Reservation community. We are now surrounded by it. Our Tribe has been fortunate to play a significant role in the economic revitalization of our neighbors. With 4,200 employees, SMSC is the largest employer in Scott County. Our success with our tribal enterprises has allowed SMSC to provide a range of governmental services to our members. It has also enabled SMSC to partner with local governments to meet our broader community’s shared needs such as roads, water and sewer systems, and emergency services. Our Tribe administers social services for children and families, mental health and chemical dependency counseling, employee assistance, emergency assistance, public works, roads, water and sewer systems, health programs and a dental clinic, vehicle fleet and physical plant maintenance, membership enrollment, education assistance, regulatory commissions, economic planning and development, enterprise management and operations, cultural programs, an active judicial system, and many other governmental services. Our tribal government assumes full responsibility for the construction of all on-Reservation infrastructure. And in many instances, our infrastructure serves the needs of the neighboring communities surrounding our Reservation. -

Was Gen. Henry Sibley's Son Hanged in Mankato?

The Filicide Enigma: Was Gen. Henry Sibley’s Son Ha nged in Ma nkato? By Walt Bachman Introduction For the first 20 years of Henry Milord’s life, he and Henry Sibley both lived in the small village of Mendota, Minnesota, where, especially during Milord’s childhood, they enjoyed a close relationship. But when the paths of Sibley and Milord crossed in dramatic fashion in the fall of 1862, the two men had lived apart for years. During that period of separation, in 1858 Sibley ascended to the peak of his power and acclaim as Minnesota’s first governor, presiding over the affairs of the booming new state from his historic stone house in Mendota. As recounted in Rhoda Gilman’s excellent 2004 biography, Henry Hastings Sibley: Divided Heart, Sibley had occupied key positions of leadership since his arrival in Minnesota in 1834, managing the regional fur trade and representing Minnesota Territory in Congress before his term as governor. He was the most important figure in 19th century Minnesota history. As Sibley was governing the new state, Milord, favoring his Dakota heritage on his mother’s side, opted to live on the new Dakota reservation along the upper Minnesota River and was, according to his mother, “roaming with the Sioux.” Financially, Sibley was well-established from his years in the fur trade, and especially from his receipt of substantial sums (at the Dakotas’ expense) as proceeds from 1851 treaties. 1 Milord proba bly quickly spe nt all of the far more modest benefit from an earlier treaty to which he, as a mixed-blood Dakota, was entitled. -

The Prairie Island Community a Remnant of MINNESOTA SIOUX

MR. MEYER is a member of the English faculty in Mankato State College. His familiarity with the history of Goodhue County, of which he is a native, combined with an interest in the Minnesota Sioux, led him to undertake the present study. The Prairie Island Community A Remnant of MINNESOTA SIOUX ROY W. MEYER A FAMILIAR THEME in American Indian recognition by the government and were al history concerns the tribe or fragment of a lowed to remain on Prairie Island, where tribe who either avoid government removal their children and grandchildren make up to some far-off reservation or who return to one of the few surviving Sioux communities their original homeland after exile. The in Minnesota today. Cherokee offer the most celebrated example. The Mdewakanton were one of the seven When they were removed from their native bands that composed the Sioux nation, and territory in the Southeastern Uplands and re the first white men to visit the Minnesota located west of the Mississippi in 1838-39, a country found them living near Mille Lacs few families remained behind and were Lake. The advance of the Chippewa, who later joined by others who fled the new area had obtained firearms from the whites, set aside for them. Their descendants hve forced them out of this region about the today on the Qualla Reservation in North middle of the eighteenth century, and they Carolina. moved southward to the lower Minnesota A Minnesota band of Mdewakanton Sioux River and the Mississippi below the Falls of provide another instance of this sort of back- St. -

2020-2023 MN STIP.Pdf

395 John Ireland Blvd. St. Paul, MN 55155 October 15, 2019 To the Reader: The State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) is a comprehensive four-year schedule of planned transportation projects in Minnesota for state fiscal years 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023. These projects are for state trunk highways, local roads and bridges, rail crossings and transit capital and operating assistance. This document represents an investment of over $6.7 billion in federal, state, and local funds over the four years. This document is the statewide transportation program in which MnDOT, local governments, and community and business interest groups worked together in eight District Area Transportation Partnerships (ATPs) to discuss regional priorities and reach agreement on important transportation investments. This state process was developed in response to the Federal “Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA) of 1991” which focused on enhanced planning processes, greater state and local government responsibility, and more citizen input to decision making. The process has continued under the following acts: The 1998 Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21); the 2005 Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU); the 2012 Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21); and the 2015 Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (FAST), signed into law December 4, 2015. Any questions and comments on specific projects included in this program may be directed to the identified MnDOT District Transportation office listed in the Program Listing sections of the document. To further assist you in using this information, a searchable database will be available by October 2019 on the Internet at: http://www.dot.state.mn.us/planning/program/stip.html To request any MnDOT document in an alternative format, please call 651-366-4720. -

Appendix Tables

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp METROPOLITAN COUNCIL’S REGIONAL PARKS SYSTEM ANNUAL USE ESTIMATE: APPENDIX TABLES July 2018 The Council’s mission is to foster efficient and economic growth for a prosperous metropolitan region Metropolitan Council Members Alene Tchourumoff Chair Edward Reynoso District 9 Katie Rodriguez District 1 Marie McCarthy District 10 Lona Schreiber District 2 Sandy Rummel District 11 Jennifer Munt District 3 Harry Melander District 12 Deb Barber District 4 Richard Kramer District 13 Steve Elkins District 5 Jon Commers District 14 Gail Dorfman District 6 Steven T. Chávez District 15 Gary L. Cunningham District 7 Wendy Wulff District 16 Cara Letofsky District 8 The Metropolitan Council is the regional planning organization for the seven-county Twin Cities area. The Council operates the regional bus and rail system, collects and treats wastewater, coordinates regional water resources, plans and helps fund regional parks, and administers federal funds that provide housing opportunities for low- and moderate-income individuals and families. The 17-member Council board is appointed by and serves at the pleasure of the governor. On request, this publication will be made available in alternative formats to people with disabilities. Call Metropolitan Council information at 651-602-1140 or TTY 651-291-0904. Appendix Tables: 2017 Regional Parks System Use Estimate Summer Winter1 Spring/Fall1 Other2 Camping Special Events Total Visits Agency/Park visits (1,000's) use multiplier visits (1,000's) use multiplier visits (1,000's) (1,000's) (1,000's) (1,000's) ANOKA COUNTY: Anoka Co. -

Dakota County Minnesota River Greenway Cultural Resources Interpretive Plan

DAKOTA COUNTY MINNESOTA RIVER GREENWAY CULTURAL RESOURCES INTERPRETIVE PLAN DRAFT - May 18th, 2017 This project has been financed in part with funds provided by the State of Minnesota from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society. TEN X TEN JIM ROE MONA SMITH TROPOSTUDIO ACKNOWLEDGMENTS DAKOTA COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS ADVISORY COMMITTEE • District 1 - Mike Slavik (chair) Julie Dorshak, City of Burnsville • District 2 - Kathleen A. Gaylord Liz Forbes, City of Burnsville • District 3 - Thomas A. Egan Jeff Jerde, Burnsville Historical Society • District 4 - Joe Atkins Kurt Chatfield, Dakota County • District 5 - Liz Workman Josh Kinney, Dakota County • District 6 - Mary Liz Holberg Beth Landahl, Dakota County • District 7 - Chris Gerlach Lil Leatham, Dakota County John Mertens, Dakota County Matthew Carter, Dakota County Historical Society DESIGN TEAM Joanna Foote, City of Eagan TEN X TEN Landscape Architecture Paul Graham, City of Eagan JIM ROE Interpretive Planning Eagan Historical Society MONA SMITH Multi-media Artist City of Lilydale TROPOSTUDIO Cost Management Friends of the Minnesota Valley Linda Loomis, Lower Minnesota River Watershed Kathy Krotter, City of Mendota Sloan Wallgren, City of Mendota Heights Aaron Novodvorsky, Minnesota Historical Society Retta James-Gasser, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources This project has been financed in part with funds Kao Thao, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources provided by the State of Minnesota from the Arts Leonard Wabash, Shakopee Mdewakanton -

Demand Based on Amount of Funding Requested Bicycle

Bicycle and Pedestrian Facilities (1 of 1) DEMAND BASED ON AMOUNT OF FUNDING REQUESTED BICYCLE AND PEDESTRIAN FACILITIES Multiuse Trails and Bicycle Facilities Federal Federal Total Rank ID Applicant Project Name Year Requested Cumulative Scores 1 2086 Hennepin County Southwest LRT Regional Trail Crossings 2018 $5,500,000 $5,500,000 899 TAB‐Approved Modal Funding Mid‐Point of Range ($21,870,000) 2 2220 Minneapolis University of Minnesota Protected Bikeways 2018 $953,976 $6,453,976 885 App Value % Cost of Funded % 3 2233 Minneapolis High Quality Connection ‐ Midtown Greenway to Lake 2018 $2,880,000 $9,333,976 848 Trail/Bike $54,741,365 86% $20,923,183 89% 4 2189 St Paul Margaret St Bicycle Boulevard & McKnight Trail 2018 $1,251,549 $10,585,525 847 Pedestrian $7,456,226 12% $1,640,000 7% 5 2114 MnDOT 5th St. SE Pedestrian/Bicycle Bridge Replacement 2018 $2,089,738 $12,675,263 841 SRTS $1,131,484 2% $953,884 4% 6 2184 Coon Rapids Coon Rapids Boulevard Trail Project 2018 $1,100,000 $13,775,263 835 TOTAL $63,329,075 100% $23,517,067 100% 7 2160 St Paul Indian Mounds Regional Park Trail 2019 $1,326,400 $15,101,663 832 REMAINING ($1,647,067) 8 2015 3 Rivers Park District Nine Mile Creek Regional Trail: West Edina Segment 2018 $5,500,000 $20,601,663 809 9 2102 Carver County TH 5 Regional Trail from CSAH 17 to CSAH 101 2018 $321,520 $20,923,183 785 10 2230 Fridley West Moore Lake Trail and Bicycle Lanes 2018 $458,832 $21,382,015 782 11 2115 MN‐DNR Gateway State Trail ‐ Hadley Ave Tunnel 2019 $1,000,000 $22,382,015 781 TAB‐Approved Modal Funding -

The Life and Times of Cloud Man a Dakota Leader Faces His Changing World

RAMSEY COUNTY All Under $11,000— The Growing Pains of Two ‘Queen Amies’ A Publication o f the Ramsey County Historical Society Page 25 Spring, 2001 Volume 36, Number 1 The Life and Times of Cloud Man A Dakota Leader Faces His Changing World George Catlin’s painting, titled “Sioux Village, Lake Calhoun, near Fort Snelling.” This is Cloud Man’s village in what is now south Minneapolis as it looked to the artist when he visited Lake Calhoun in the summer of 1836. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. See article beginning on page 4. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Farnham Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz RAMSEY COUNTY Volume 36, Number 1 Spring, 2001 HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Howard M. Guthmann CONTENTS Chair James Russell 3 Letters President Marlene Marschall 4 A ‘Good Man’ in a Changing World First Vice President Cloud Man, the Dakota Leader, and His Life and Times Ronald J. Zweber Second Vice President Mark Dietrich Richard A. Wilhoit Secretary 25 Growing Up in St. Paul Peter K. Butler All for Under $11,000: ‘Add-ons,’ ‘Deductions’ Treasurer The Growing Pains of Two ‘Queen Annes’ W. Andrew Boss, Peter K. Butler, Norbert Conze- Bob Garland mius, Anne Cowie, Charlotte H. Drake, Joanne A. Englund, Robert F. Garland, John M. Harens, Rod Hill, Judith Frost Lewis, John M. Lindley, George A. Mairs, Marlene Marschall, Richard T. Publication of Ramsey County History is supported in part by a gift from Murphy, Sr., Richard Nicholson, Linda Owen, Clara M. Claussen and Frieda H. Claussen in memory of Henry H. -

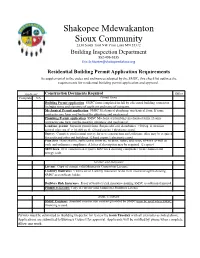

Permit: Requirements Checklist

Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community 2330 Sioux Trail NW Prior Lake MN 55372 Building Inspection Department 952‐496‐6135 [email protected] Residential Building Permit Application Requirements As supplemental to the codes and ordinances adopted by the SMSC, this checklist outlines the requirements for residential building permit application and approval. Applicant Construction Documents Required Office Complete NA Permit Items Building Permit application SMSC form completed in full by a licensed building contractor. Includes name and signature of applicant and name of company. Mechanical Permit application SMSC Mechanical plumbing/ mechanical form. If same contractor one form may be used for plumbing and mechanical. Plumbing Permit application SMSC Mechanical plumbing/ mechanical form. If same contractor one form may be used for plumbing and mechanical. Land use permit Separate permit form. Required if soil disturbance .>500 sq. ft. Erosion control plan req. if > 10,000 sq. ft. (2 hard copies 1 electronic copy). Survey Complete professional survey for new construction and additions. Also may be required for pools and other out buildings. (2 hard copies 1 electronic copy) Plan Sets Plans shall be sufficient to show the location, nature and scope of work as well as code and ordinance compliance. A letter of description may be required. (2 copies) MNCheck New construction requires MNCheck showing compliance to mechanical and energy code. License and Insurance License Copy of current valid Minnesota Contractors License Liability Insurance Certificate of Liability Insurance faxed from insurance agent showing SMSC as certificate holder. Builders Risk Insurance Proof of builder's risk insurance naming SMSC as additional insured. Plumbers License Copy of current valid Minnesota Plumbers License SMSC Contract SMSC Contract Standard construction contract provided by SMSC must be used when SMSC financing is used. -

City of West St. Paul 1616 Humboldt Avenue, West St

CITY OF WEST ST. PAUL 1616 HUMBOLDT AVENUE, WEST ST. PAUL, MN 55118 _______________________________________________________ OPEN COUNCIL WORK SESSION MUNICIPAL CENTER LOBBY CONFERENCE ROOM FEBRUARY 25, 2019 5:00 P.M. 1. Roll Call 2. Review and Approve the OCWS Agenda 3. Review the Regular Meeting Consent Agenda 4. Agenda Item(s) A. Appointment of Councilmember Eng-Sarne to Environmental Committee, Public Safety Committee and Thompson Park Advisory Board Documents: COUNCIL REPORT - APPOINTMENTS TO COMMITTEES AND COMMISSIONS.PDF B. Update on House Bills Documents: 2019 BILL INTRODUCTIONS.PDF RESOLUTION - GRANTING BILL SUPPORT 022519.PDF C. Debrief on the February 21, 2019 Listening Session (Neighborhood Meeting) Documents: MINUTES - NEIGHBORHOOD MTG 2-21-19.PDF D. Strategic Plan Update and Review Agenda Documents: WEST ST. PAUL STRATEGIC INITIATIVES AGENDA (FINAL).PDF E. Right of Way Obstruction Permit, No Parking Ordinance Language Addition Documents: COUNCIL REPORT - RIGHT OF WAY OBSTRUCTION PERMIT.PDF F. Sidewalk District/Funding Analysis Documents: COUNCIL REPORT - OCWS SIDEWALK DISTRICT FUNDING ANALYSIS.PDF ATTACHMENT - PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE MASTER PLAN.PDF 5. Adjourn If you need an accommodation to participate in the meeting, please contact the ADA Coordinator at 651-552-4100, TDD 651-322-2323 at least 5 business days prior to the meeting www.wspmn.gov EOE/AA CITY OF WEST ST. PAUL 1616 HUMBOLDT AVENUE, WEST ST. PAUL, MN 55118 _______________________________________________________ OPEN COUNCIL WORK SESSION MUNICIPAL CENTER LOBBY CONFERENCE ROOM FEBRUARY 25, 2019 5:00 P.M. 1. Roll Call 2. Review and Approve the OCWS Agenda 3. Review the Regular Meeting Consent Agenda 4. Agenda Item(s) A. -

Minnesota Bounties on Dakota Men During the U.S.-Dakota War Colette Routel Mitchell Hamline School of Law, [email protected]

Mitchell Hamline School of Law Mitchell Hamline Open Access Faculty Scholarship 2013 Minnesota Bounties On Dakota Men During The U.S.-Dakota War Colette Routel Mitchell Hamline School of Law, [email protected] Publication Information 40 William Mitchell Law Review 1 (2013) Repository Citation Routel, Colette, "Minnesota Bounties On Dakota Men During The .SU .-Dakota War" (2013). Faculty Scholarship. Paper 260. http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/facsch/260 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Minnesota Bounties On Dakota Men During The .SU .-Dakota War Abstract The .SU .-Dakota War was one of the formative events in Minnesota history, and despite the passage of time, it still stirs up powerful emotions among descendants of the Dakota and white settlers who experienced this tragedy. Hundreds of people lost their lives in just over a month of fighting in 1862. By the time the year was over, thirty-eight Dakota men had been hanged in the largest mass execution in United States history. Not long afterwards, the United States abrogated its treaties with the Dakota, confiscated their reservations along the Minnesota River, and forced most of the Dakota to remove westward. While dozens of books and articles have been written about these events, scholars have largely ignored an important legal development that occurred in Minnesota during the following summer. The inneM sota Adjutant General, at the direction of Minnesota Governors Alexander Ramsey and Henry Swift, issued a series of orders offering rewards for the killing of Dakota men found within the State. -

Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings and Standards

Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings & Standards (Draft Revision) Oceti Sakowin [oh-CHEH-tee SHAW-koh-we] means “Seven Council Fires” and refers collectively to the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota people. TABLE OF CONTENTS History of Development of the Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings and Standards . 1 OSEU at a Glance . 3 OSEU 1 . 4 OSEU 2 . 6 OSEU 3 . 8 OSEU 4 . 10 OSEU 5 . 12 OSEU 6 . 14 OSEU 7 . 17 OSEU Standards with Suggested Approaches for Instruction . 19 History Tables of the Oceti Sakowin & Teton . 21 Current Locations of Oceti Sakowin Bands . 30 Map of South Dakota Reservations . 31 Glossary of Terms . 32 Bibliography . 33 About the Cover Artist: Merle Locke Merle is an Oglala Lakota artist who resides in Porcupine, South Dakota. His paintings are very symbolic in nature depicting traditional tribal scenes and imagery. The symbolism of the cover painting for the Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings and Standards Project is representative of several meanings. TheOceti Sakowin tradition of oral teaching among generations is depicted by showing an elder in the center. The elder is surrounded by seven people who represent different generations. The people, as well as the seven tipis, represent theOceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires). The dragon flies represent hope and prosperity with the thoughts of bringing goodness to the tribes and people. A HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE OCETI SAKOWIN ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDINGS AND STANDARDS “The hope is that citizens who are well educated about theOceti Sakowin history and culture will be more likely to make better decisions in the arena of Indian issues and to get along better with one another.” - Lakota Scholar, Dr.