Introduction to Phantoms of the Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher's Notes

PENGUIN READERS Teacher’s notes LEVEL 5 Teacher Support Programme The Phantom of the Opera Gaston Leroux underground house on the lake below the Opera. She believes he is the Angel of Music, who her father promised to send after he died. To her horror she discovers, when she sees him for the first time that she is in the grip of a terrible monster. Count Chagny’s brother Raoul, the viscount, is also in love with Christine but she cannot return his love for fear of what the monster will do if he finds them together. The monster and the viscount are jealous of each other, but the monster is far cleverer and Raoul ends up in Erik’s torture room with the Persian who is helping him find Christine. When it seems that there is no hope and that they will die in the torture room, the Persian reminds Erik that he once saved Erik’s About the author life. This saves the two men. When Christine touches the monster’s hand, mixes her tears with his, and allows the Gaston Leroux, born in Paris in 1868, was trained in monster to kiss her, he has his first and last taste of human law, but chose a career in writing. He wrote stories, plays, affection and love. How can he now allow Christine to poems, novels and screenplays. His own extensive travels go away with Raoul? We learn towards the end of the around the world and his knowledge of the layout of the story that Erik was born with no nose and yellow eyes. -

The Life Artistic: July / August 2016 Wes Anderson + Mark Mothersbaugh

11610 EUCLID AEUE, CLEELAD, 44106 THE LIFE ARTISTIC: JULY / AUGUST 2016 WES ANDERSON + MARK MOTHERSBAUGH July and August 2016 programming has been generously sponsored by TE LIFE AUATIC ... AUATIC TE LIFE 4 FILMS! ALL 35MM PRINTS! JULY 7-29, 2016 THE CLEVELAND INSTITUTE OF ART CINEMATHEQUE 11610 EUCLID AVENUE, UNIVERSITY CIRCLE, CLEVELAND OHIO 44106 The Cleveland Institute of Art Cinematheque is Cleveland’s alternative film theater. Founded in 1986, the Cinematheque presents movies in CIA’s Peter B. Lewis Theater at 11610 Euclid Avenue in the Uptown district of University Circle. This new, 300-seat theater is equipped with a 4K digital cinema projector, two 35mm film projectors, and 7.1 Dolby Digital sound. Free, lighted parking for filmgoers is currently available in two CIA lots located off E. 117th Street: Lot 73 and the Annex Lot. (Those requiring disability park- ing should use Lot 73.) Enter the building through Entrance C (which faces E. 117th) or Entrance E (which faces E. 115th). Unless noted, admission to each screening is $10; Cinematheque members, CIA and Cleveland State University I.D. holders, and those age 25 & under $7. A second film on LOCATION OF THE the same day generally costs $7. For further information, visit PETER B. LEWIS THEATER (PBL) cia.edu/cinematheque, call (216) 421-7450, or send an email BLACK IL to [email protected]. Smoking is not permitted in the Institute. TH EACH FILM $10 • MEMBERS, CIA, AGE 25 & UNDER $7 • ADDITIONAL FILM ON SAME DAY $7 OUR 30 ANNIVERSARY! FREE LIGHTED PARKING • TEL 216.421.7450 • CIA.EDU/CINEMATHEQUE BLOOD SIMPLE TIKKU INGTON TE LIFE ATISTIC: C I N E M A T A L K ES ADES AK TESBAU ul 72 (4 lms) obody creates cinematic universes like es Anderson. -

Allusions and Historical Models in Gaston Leroux's the Phantom of the Opera

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 2004 Allusions and Historical Models in Gaston Leroux's The Phantom of the Opera Joy A. Mills Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mills, Joy A., "Allusions and Historical Models in Gaston Leroux's The Phantom of the Opera" (2004). Honors Theses. 83. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/83 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gaston Leroux's 1911 novel, The Phantom of the Opera, has a considerable number of allusions, some of which are accessible to modern American audiences, like references to Romeo and Juilet. Many of the references, however, are very specific to the operatic world or to other somewhat obscure fields. Knowledge of these allusions would greatly enhance the experience of readers of the novel, and would also contribute to their ability to interpret it. Thus my thesis aims to be helpful to those who read The Phantom of the Opera by providing a set of notes, as it were, to explain the allusions, with an emphasis on the extended allusion of the Palais Garnier and the historical models for the heroine, Christine Daae. Notes on Translations At the time of this writing, three English translations are commercially available of The Phantom of the Opera. -

Phantom of the Paradise De Brian De Palma (1974)

Thème de la musique avant toute chose. Fiche cinéma 1 Phantom of the Paradise de Brian de Palma (1974) Synopsis : Un compositeur talentueux, Wislow Leach, inconnu et pauvre, vient d’écrire l’œuvre de sa vie : Faust,l’opéra rock, il vient proposer sa musique à une Major ; celle de Swan. Il sera dépouillé de son œuvre, emprisonné à Sing Sing sans raison et, dans un acte de folie, voulant récupérer son bien, va être victime d’un accident terrible dans les presses de la maison de disque. Devenant le « phantom » de lui-même, et du théâtre « Paradise » où doit se jouer son œuvre, il signera finalement un contrat avec Swan qui sera aussi celui de sa mort et dans lequel, sans s’en rendre compte, il se dépouille de son œuvre et de son âme. Dans ce film Brian de Palma fait le portrait d’une industrie liée au monde de la musique peu glorieuse, il nous en montre tous les travers. Il est une évidence, ce film colle au thème de la musique avant toute chose. Nous sommes dans l’univers musical de la production : maison de disque « Death Records », interprétation de Juicy Fruits « juteux pour le producteur ». Le producteur Swan, pour lui la musique n’est qu’une question d’argent. I/Les thèmes évoqués : -La drogue : Être sous stupéfiants pour se dépasser et aussi pour profiter de l’autre. -Le sexe : Il n’est pas tant libéré que cela, on comprend rapidement que le sexe n’existe que pour le bénéfice que l’on peut en retirer «de la musique avant toute chose » mis en place d’une certaine ironie. -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence. -

Film Reviews

Page 104 FILM REVIEWS “Is this another attack?”: Imagining Disaster in C loverfield, Diary of the Dead and [ Rec] Cloverfield (Dir. Matt Reeves) USA 2007 Paramount Home Entertainment Diary of the Dead (Dir. George A. Romero) USA 2007 Optimum Home Entertainment [Rec] (Dir. Jaume Balagueró & Paco Plaza) S pain 2007 Odeon Sky Filmworks In 1965, at the height of the Cold War, Susan Sontag declared in her famous essay ‘The Imagination of Disaster’ that the world had entered an “age of extremity” in which it had become clear that from now until the end of human history, every person on earth would “spend his individual life under the threat not only of individual death, which is certain, but of something almost insupportable psychologically – collective incineration which could come at any time”. Sontag went on to claim that narratives in which this fate was dramatised for the mass audience in fantastical form – like the monster movies of the 1950s – helped society deal with this stress by distracting people from their fate and normalising what was psychologically unbearable: a kind of vaccination of the imagination, if you will. If this is the case, then Cloverfield, in which Manhattan is destroyed by an immensely powerful sea monster, George A. Romero’s latest zombie movie, Diary of the Dead, and claustrophobic Spanish hit [Rec] are not so much preemptive vaccinations against probable catastrophe, but intermittently powerful, if flawed, reminders of actual calamity. In all three films some of the most destabilising events and anxieties of the past decade – including 9/11 (and the fear of terrorist attacks striking at the heart of American and European cities), Hurricane Katrina, the 2004 Tsunami, and the SARS virus– are reconfigured as genrebased mass market entertainment. -

THE MASK of ERIK by Rick Lai © 2007 Rick Lai [email protected] In

THE MASK OF ERIK by Rick Lai © 2007 Rick Lai [email protected] In The Phantom of the Opera (1910), Gaston Leroux (1868-1927) created a colorful past for the title character who was also known as Erik. Leroux pretended that his novel was not a work of fiction. He perpetrated the hoax that the Phantom’s story had been unearthed through interviews with actual people including former employees of the Paris Opera House. A careful reading of the novel indicates that its events transpired decades before its year of publication. The novel’s prologue indicated that the story took place “not more than thirty years ago.” At one point, Erik made the farcical prediction that a young girl, Meg Giry, would be an Empress in 1885. The novel happened sometime between 1880 and 1884. Of the years available, I favor 1881 (1). The Phantom was born in a French town not far from Rouen. His exact year of birth was unstated, but it was probably around 1830 (2). The Phantom’s skeletal visage was a defect from birth. The makeup of Lon Chaney Sr. in the famous 1925 silent movie faithfully followed Leroux’s description of the Phantom’s face. Since the silent film was made in black and white, Chaney could never duplicate the bizarre yellow eyes of the Phantom. Very little is known of the Phantom’s parents (3). His father was a stonemason. The Phantom’s mother was repelled by her son’s ugliness. She refused to ever let him kiss her. Furthermore, she insisted that he wear a mask at all times. -

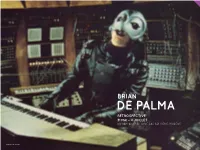

Brian De Palma Brian De Programmation

BRIAN DE PALMA BRIAN DE PROGRAMMATION BRIAN DE PALMA RÉTROSPECTIVE 31 MAI – 4 JUILLET EN PARTENARIAT AVEC LES ÉDITIONS RIVAGES Phantom of the Paradise 28 29 MÉCANIQUES FATALES Brian De Palma est l’auteur d’un cinéma politique et critique au cœur même de Hollywood et de l’Amérique de l’après-Vietnam (Phantom of the Paradise, Blow Out, Scarface, Outrages…). C’est une œuvre tout à la fois sombre et spec- taculaire, référentielle et constamment inventive : comme si De Palma n’avait jamais cessé de reprendre des images venant du cinéma, celles de Hitchcock en particulier, et de leur redonner vie dans un véritable feu d’artifice formel BRIAN DE PALMA BRIAN DE (Obsession, Pulsions, Body Double…). Rétrospective intégrale des films de ce cinéaste-inventeur à l’occasion de sa venue en France pour la sortie de son pre- mier roman, co-écrit avec Susan Lehman : Les serpents sont-ils nécessaires ? (éditions Rivages). Scarface LA CHAMBRE NOIRE Adolescent, découvrir les films de Brian De Palma c’était rencontrer le cinéma lui- Au cours d’une carrière qui épousa parfois celle de ses compagnons de route : même. Lorsque Carrie embrasait le bal de l’école, il n’y avait pas seulement une Scorsese, Coppola ou Spielberg, il a connu le succès avec des épopées mafieuses image sur l’écran mais deux et même trois. Dans Pulsions, pendant dix minutes (Scarface, Les Incorruptibles), joué les artificiers pour Tom Cruise (Mission : muettes, la caméra en apesanteur suivait Angie Dickinson dans les allées d’un Impossible), adapté des best-sellers (Le Bucher des vanités) ou abordé les « grands musée, en une sidérante anamorphose de la mort et du désir. -

The Phantom on Film: Guest Editor’S Introduction

The Phantom on Film: Guest Editor’s Introduction [accepted for publication in The Opera Quarterly, Oxford University Press] © Cormac Newark 2018 What has the Phantom got to do with opera? Music(al) theater sectarians of all denominations might dismiss the very question, but for the opera studies community, at least, it is possible to imagine interesting potential answers. Some are historical, some technical, and some to do with medium and genre. Others are economic, invoking different commercial models and even (in Europe at least) complex arguments surrounding public subsidy. Still others raise, in their turn, further questions about the historical and contemporary identities of theatrical institutions and the productions they mount, even the extent to which particular works and productions may become institutions themselves. All, I suggest, are in one way or another related to opera reception at a particular time in the late nineteenth century: of one work in particular, Gounod’s Faust, but even more to the development of a set of popular ideas about opera and opera-going. Gaston Leroux’s serialized novel Le Fantôme de l’Opéra, set in and around the Palais Garnier, apparently in 1881, certainly explores those ideas in a uniquely productive way.1 As many (but perhaps not all) readers will recall, it tells the story of the debut in a principal role of Christine Daaé, a young Swedish soprano who is promoted when the Spanish prima donna, Carlotta, is indisposed.2 In the course of a gala performance in honor of the outgoing Directors of the Opéra, she is a great success in extracts of works 1 The novel was serialized in Le Gaulois (23 September 1909–8 January 1910) and then published in volume-form: Le Fantôme de l’Opéra (Paris: Lafitte, 1910). -

DE PALMA, Brían (Newark, New Jersey, 1940). Menos Respetado

DE PALMA, Brían (Newark, New Jersey, 1940). Menos respetado por la critica que Scorsese, de carrera menos comercial que Spielberg, De Palma ocupa una posición relativamente frágil e inestable (si bien nunca marginal) dentro del panteón de los movie brats. Pero sus películas, quizá más que las de ninguno, revelan un genuino plaisir du cinéma, una dionisiaca utilización del tren eléctrico más caro del mundo; una notable perversidad, siempre a un paso de entrar de lleno en la estética trash (es famosa su réplica a la feminista Marcia Pally de que nada es comparable al impacto plástico de asesinar a una chica sexy; y en alguna ocasión ha tenido la idea de hacer cine porno); y una residual pero notable voluntad modernista, procedente de su etapa underground, que se traduce en su perceptible desinterés por la dramaturgia y la narrativa convencionales y, desde luego, por la verosimilitud: rueda con desgana las escenas transicionales o explicativas que en su cine, y sobre todo en el menos conseguido; son casi todas menos aquellas escenas fuertes en las que concentra todo su aparato formal, sus famosas set- pieces: un virtuoso ejercicio de estilo o de lucimiento cinemático traducido en la condensación/dilatación de la acción en una coreografía plástica de la violencia. Su actitud posclásica se revela también en su gusto por la repetición (el último y brillante ejemplo: Femme Fatale, [2002]), la split-screen (desde Dyonisos in '69 [1970]) Y el falso final (que patentó en Carrie [1976]); las secuencias oníricas (a menudo su cine parece una ilustración del traumwerk freudiano) y las metáforas sobre la visión (tecnológicas: el video; y narrativas: el voyeurismo); y por supuesto en su posmoderna afición a la cita y el pastiche, de Hitchcock principalmente, De Palma empieza a hacer sus primeras películas amateur cuando todavía se encuentra cursando estudios en la Columbia University, en donde conoce el cine de Hitchcock y descubre que la esencia del cine radica en la manipulación del punto de vista. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Into the Light a Phantom of the Opera Story by Debra P. Whitehead Into the Light: a Phantom of the Opera Story by Debra P

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Into the Light A Phantom of the Opera Story by Debra P. Whitehead Into the Light: A Phantom of the Opera Story by Debra P. Whitehead. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 660859611d062bc6 • Your IP : 116.202.236.252 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Into the Light: A Phantom of the Opera Story by Debra P. Whitehead. Published Mar 20, 2008 448 Pages Genre: HUMOR / General. Looking for Kindle/Audio editions? Browse Amazon for all formats. Searching for the Nook edition? Browse Barnes & Noble. Book Details. What Do You Do When a Dead Man Moves to Town? Millie would not be intimidated, not by the likes of him. As if he read her thoughts, his mouth curled at one corner in a crude caricature of a smile. A wave of foreboding clawed its way up her spine. She was going to regret selling him the house. Hanover, Tennessee is a community of honest family values and simple pleasures, a place comfortably wrapped in generations of sameness. -

The PHANTOM of the OPERA

ELBERT COUNTY TRIBUNE. nin»-- your cer- known to FRIENDS SAID risk life for her! You "It’s not turning! . , , a Mcret paa«*«. lon* MY must And U“* tainly Christine, alone and contrlYed at bate Erik!" sir, Christine?" aolf u»e ( Could Never Get Well “No, sir,” the sadly, said coldly: of the Commune to allow said Persian Tbe Persian Paris ®° their P rl ner to Peruna I am Well. "I do not hate him. If I hated him, "We shall do ail that It Is humanly to convey Thanks Jailers that naa he would long ago have ceased doing possible to straight to the dungeons In the cel- barm." stop us at the first step! ... constructed for them He been occupied "Has begone you harm?" commands tbe walls, the doors and lars; for tbe Federates had after the "I have forgiven him the barm the trap-doors. In my country, he was the opera-house immediately The PHANTOM which he has done me." known a and had made a by name which means the eighteenth of March " or "I not you. You ‘trap-door starting-place right at the top do understand lover.' car- treat him as a monster, you or “But why do walla their Mongolfler balloons, which speak tbe6e obey him to his crime, he has done you barm and alone? He did not build them!” ried their incendiary proclamations prison 1 find In you the same Inexplicable “Yes, sir, that Is Just what he did!" the departments, and a state OF OPERA pity that drove me to despair when i Raoul looked at him in amazement; right at the bottom.