Master's Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

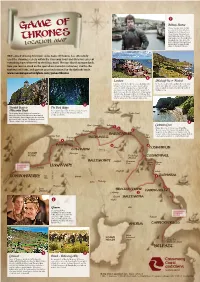

GAME of THRONES® the Follow Tours Include Guides with Special Interest and a Passion for the Game of Thrones

GAME OF THRONES® The follow tours include guides with special interest and a passion for the Game of Thrones. However you can follow the route to explore the places featured in the series. Meet your Game of Thrones Tours Guide Adrian has been a tour guide for many years, with a passion for Game of Thrones®. During filming he was an extra in various scenes throughout the series, most noticeably, a stand in double for Ser Davos. He is also clearly seen guarding Littlefinger before his final demise at the hands of the Stark sisters in Winterfell. Adrian will be able to bring his passion alive through his experience, as well as his love of Northern Ireland. Cairncastle ~ The Neck & North of Winterfell 1 Photo stop of where Sansa learns of her marriage to Ramsay Bolton, and also where Ned beheads Will, the Night’s Watch deserter. Cairncastle Refreshment stop at Ballygally Castle, Ballygally Located on the scenic Antrim coast facing the soft, sandy beaches of Ballygally Bay. The Castle dates back to 1625 and is unique in that it is the only 17th Century building still used as a residence in Northern Ireland today. The hotel is reputedly haunted by a friendly ghost and brave guests can visit the ‘ghost room’ in one of the towers to see for themselves. View Door No. 9 of the Doors of Thrones and collect your first stamp in your Journey of Doors passport! In the hotel foyer you will be able to admire the display cabinets of the amazing Steensons Game of Thrones® inspired jewellery. -

Mhysa Or Monster: Masculinization, Mimicry, and the White Savior in a Song of Ice and Fire

Mhysa or Monster: Masculinization, Mimicry, and the White Savior in A Song of Ice and Fire by Rachel Hartnett A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL August 2016 Copyright 2016 by Rachel Hartnett ii Acknowledgements Foremost, I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude to my advisor Dr. Elizabeth Swanstrom for her motivation, support, and knowledge. Besides encouraging me to pursue graduate school, she has been a pillar of support both intellectually and emotionally throughout all of my studies. I could never fully express my appreciation, but I owe her my eternal gratitude and couldn’t have asked for a better advisor and mentor. I also would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Dr. Eric Berlatsky and Dr. Carol McGuirk, for their inspiration, insightful comments, and willingness to edit my work. I also thank all of my fellow English graduate students at FAU, but in particular: Jenn Murray and Advitiya Sachdev, for the motivating discussions, the all-nighters before paper deadlines, and all the fun we have had in these few years. I’m also sincerely grateful for my long-time personal friends, Courtney McArthur and Phyllis Klarmann, who put up with my rants, listened to sections of my thesis over and over again, and helped me survive through the entire process. Their emotional support and mental care helped me stay focused on my graduate study despite numerous setbacks. Last but not the least, I would like to express my heart-felt gratitude to my sisters, Kelly and Jamie, and my mother. -

El Ecosistema Narrativo Transmedia De Canción De Hielo Y Fuego”

UNIVERSITAT POLITÈCNICA DE VALÈNCIA ESCOLA POLITE CNICA SUPERIOR DE GANDIA Grado en Comunicación Audiovisual “El ecosistema narrativo transmedia de Canción de Hielo y Fuego” TRABAJO FINAL DE GRADO Autor/a: Jaume Mora Ribera Tutor/a: Nadia Alonso López Raúl Terol Bolinches GANDIA, 2019 1 Resumen Sagas como Star Wars o Pokémon son mundialmente conocidas. Esta popularidad no es solo cuestión de extensión sino también de edad. Niñas/os, jóvenes y adultas/os han podido conocer estos mundos gracias a la diversidad de medios que acaparan. Sin embargo, esta diversidad mediática no consiste en una adaptación. Cada una de estas obras amplia el universo que se dio a conocer en un primer momento con otra historia. Este conjunto de historias en diversos medios ofrece una narrativa fragmentada que ayuda a conocer y sumergirse de lleno en el universo narrativo. Pero a su vez cada una de las historias no precisa de las demás para llegar al usuario. El mundo narrativo resultante también es atractivo para otros usuarios que toman parte de mismo creando sus propias aportaciones. A esto se le conoce como narrativa transmedia y lleva siendo objeto de estudio desde principios de siglo. Este trabajo consiste en el estudio de caso transmedia de Canción de Hielo y Fuego la saga de novelas que posteriormente se adaptó a la televisión como Juego de Tronos y que ha sido causa de un fenómeno fan durante la presente década. Palabras clave: Canción de Hielo y Fuego, Juego de Tronos, fenómeno fan, transmedia, narrativa Summary Star Wars or Pokémon are worldwide knowledge sagas. This popularity not just spreads all over the world but also over an age. -

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

Racialization, Femininity, Motherhood and the Iron Throne

THESIS RACIALIZATION, FEMININITY, MOTHERHOOD AND THE IRON THRONE GAME OF THRONES AS A HIGH FANTASY REJECTION OF WOMEN OF COLOR Submitted by Aaunterria Treil Bollinger-Deters Department of Ethnic Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2018 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Ray Black Joon Kim Hye Seung Chung Copyright by Aaunterria Bollinger 2018 All Rights Reserved. ABSTRACT RACIALIZATION, FEMININITY, MOTHERHOOD AND THE IRON THRONE GAME OF THRONES A HIGH FANTASY REJECTION OF WOMEN OF COLOR This analysis dissects the historic preconceptions by which American television has erased and evaded race and racialized gender, sexuality and class distinctions within high fantasy fiction by dissociation, systemic neglect and negating artistic responsibility, much like American social reality. This investigation of high fantasy creative fiction alongside its historically inherited framework of hierarchal violent oppressions sets a tone through racialized caste, fetishized gender and sexuality. With the cult classic television series, Game of Thrones (2011-2019) as example, portrayals of white and nonwhite racial patterns as they define womanhood and motherhood are dichotomized through a new visual culture critical lens called the Colonizers Template. This methodological evaluation is addressed through a three-pronged specified study of influential areas: the creators of Game of Thrones as high fantasy creative contributors, the context of Game of Thrones -

GAME of THRONES Itinerary Leaving Belfast and Heading North, Cairncastle Is Your Destination and We’Re Right Back to the Very First Episode

The Cushendun Caves GAME OF THRONES itinerary Leaving Belfast and heading north, Cairncastle is your destination and we’re right back to the very first episode. This three-day itinerary brings you right into It was here that Ned Stark took his long-sword Ice and the bloody heart of the Seven Kingdoms. struck off the head of a Night’s Watch deserter, as John, Along the route, we’ll pass through the most Bran, Rob and Theon looked on. Heading west from memorable locations from the show, where Cairncastle, the Shillanavogy Valley is your next stop. This was where the ferocious Dothraki hoard set up camp, and the wicked Lannisters, honourable Starks the verdant, green valley was seamlessly transformed and all the rest play out their parts. into the swaying grasslands of Vaes Dothrak. The journey continues to Glenariff Forest Park taking you to the Fight practice ground at Runestone, seat of House Royce in the So sharpen your sword, tighten your shield- Vale of Arryn which is located east of the Eyrie, on the strap and set forth on a journey into the real coast of the Narrow Sea. You will recall that Robin Arryn world Westeros. has been sent to Runestone, where Royce's men are training him to use a sword under the watchful eye of Littlefinger, Sansa Stark and Yohn Royce. Head north east towards Antrim’s stunning coastline: the Cushendun Caves are calling. Davos Seaworth acted against his better judgment when he escorted Lady Melisandre on her quest to assassinate Renly Baratheon. We travel from this small seaside town to explore several The Cushendun Caves were used for the unforgettable more Game of Thrones settings. -

Narrative Structure of a Song of Ice and Fire Creates a Fictional World

Narrative structure of A Song of Ice and Fire creates a fictional world with realistic measures of social complexity Thomas Gessey-Jonesa , Colm Connaughtonb,c , Robin Dunbard , Ralph Kennae,f,1 ,Padraig´ MacCarrong,h, Cathal O’Conchobhaire , and Joseph Yosee,f aFitzwilliam College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0DG, United Kingdom; bMathematics Institute, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, United Kingdom; cLondon Mathematical Laboratory, London W6 8RH, United Kingdom; dDepartment of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, e f 4 Oxford OX2 6GG, United Kingdom; Centre for Fluid and Complex Systems, Coventry University, Coventry CV1 5FB, United Kingdom; L Collaboration, Institute for Condensed Matter Physics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 79011 Lviv, Ukraine; gMathematics Applications Consortium for Science and Industry, Department of Mathematics & Statistics, University of Limerick, Limerick V94 T9PX, Ireland; and hCentre for Social Issues Research, University of Limerick, Limerick V94 T9PX, Ireland Edited by Kenneth W. Wachter, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved September 15, 2020 (received for review April 6, 2020) Network science and data analytics are used to quantify static and Schklovsky and Propp (11) and developed by Metz, Chatman, dynamic structures in George R. R. Martin’s epic novels, A Song of Genette, and others (12–14). Ice and Fire, works noted for their scale and complexity. By track- Graph theory has been used to compare character networks ing the network of character interactions as the story unfolds, it to real social networks (15) in mythological (16), Shakespearean is found that structural properties remain approximately stable (17), and fictional literature (18). To investigate the success of Ice and comparable to real-world social networks. -

“I'm All That Stands Between Them and Chaos:” a Monstrous Way of Ruling In

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00562-3 OPEN “I’m all that stands between them and chaos:” a monstrous way of ruling in A Song of Ice and Fire ✉ Györgyi Kovács 1 The article explores Tyrion Lannister’s rule in King’s Landing in the second volume of A Song of Ice and Fire books, A Clash of Kings. In the reception of ASOIAF and the TV show Game of Thrones, Tyrion was considered one of the best rulers, and the TV show ended by making him 1234567890():,; Hand to a king who delegated the greatest part of ruling to him. The analysis is based on Foucault’s notion of monstrosity in power, which is characterized by a monstrous conduct and includes the excess and potential abuse of power. The article argues that monstrosity in his rule reveals deeper layers in Tyrion’s personality, which is initially suggested to be defined by morality. The article also comes to the conclusion that his morality limits the scope of his monstrous methods, which eventually leads to his fall from power. ✉ 1 Eötvös Loránd University, Faculty of Humanities, Budapest, Hungary. email: [email protected] HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2020) 7:70 | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00562-3 1 ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00562-3 Introduction ne of the most compelling features of George R. R. of his character and anticipates that in the books Tyrion will turn OMartin’s A Song of Ice and Fire (ASOIAF) books is the a villain motivated by vengeance (Bryndenbfish, 2019), which is way they present a richly detailed medieval fantasy world exactly the opposite of how his storyline ended in the TV show. -

A Game of Thrones a Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin

A Game of Thrones A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin Book One: A Game of Thrones Book Two: A Clash of Kings Book Three: A Storm of Swords Book Four: A Feast for Crows Book Five: A Dance with Dragons Book Six: The Winds of Winter (being written) Book Seven: A Dream of Spring “ Fire – Dragons, Targaryens Lord of Light Ice – Winter, Starks, the Wall White Walkers Spoilers!! Humans as meaning-makers – Jerome Bruner Humans as story-tellers – narrative theory Humans as mythopoeic–Carl G. Jung, Joseph Campbell The mythic themes in A Song of Ice and Fire are ancient Carl Jung: Archetypes are powerful & primordial images & symbols Collective unconscious Carl Jung’s archetypes Great Mother; Father; Hero; Savior… Joseph Campbell – The Power of Myth The Hero’s Journey Carole Pearson – the 12 archetypes Ego stage: Innocent; Orphan; Caretaker; Warrior Soul transformation: Seeker; Destroyer; Lover; Creator; Self: Ruler; Magician; Sage; Fool Maureen Murdock – The Heroine’s Journey The Great Mother (& Maiden, & Crone), the Great Father, the child, the Shadow, the wise old man, the trickster, the hero…. In the mystery of the cycle of seasons In ancient gods & goddesses In myth, fairy tale & fantasy & the Seven in A Game of Thrones The Gods: The Old Gods The Seven (Norse mythology): Maiden, Mother, Crone Father, Warrior, Smith Stranger (neither male or female) R’hilor (Lord of light) Others: The Drowned God, Mother Rhoyne The family sigils Stark - Direwolf Baratheon – Stag Lannister – Lion Targaryen -

Game of Thrones Location

7 Ballintoy Harbour This picturesque inlet doubled as Lordsport Harbour (The Iron Islands) for the homecoming of Theon Greyjoy. The beach and bay at Ballintoy is where Theon was baptized into the faith of the ‘Drowned God’, and where the pirate Salladhor Sann met Davos Location Map and pledged his support (and ships) to Stannis Baratheon. © HBO HBO’s award-winning television series Game Of Thrones has extensively used the stunning scenery within the Causeway Coast and Glens to represent everything from Winterfell to the King’s Road, The Iron Islands to Stormlands. Now you too can stand on the spot where Lannisters schemed, stroll in the footsteps of Starks, and gaze on grasslands crossed by the Dothraki horde. www.causewaycoastandglens.com/gameofthrones 6 5 Larrybane Murlough Bay & Fairhead Larrybane hosted several key scenes, including where Used as the road to Pyke on which Theon Greyjoy Brienne beats Ser Loras in a tourney and is given and his sister Asha ride on horseback, and where a place in Renly’s Kingsguard as a reward. Renly Davos Seaworth is shipwrecked after the Battle of also swears to Lady Stark that he will avenge Ned’s Blackwater Bay. death, but meets his end at the hands of Melisandre’s shadow baby; Margaery confides to Littlefinger that she wants to be Queen; and Davos tries to tell Stannis what he witnessed in the cave with Melisandre. 9 8 Downhill Beach & T he Dark Hedges Mussenden Temple This is where Arya Stark, dressed as a boy, escaped The beautiful beach doubled as Dragonstone, from King’s Landing in the company of Yoren, Rathlin Island where the Seven Idols of Westeros were burned Gendry, and Hot Pie. -

Klawitter.Pdf

White olk Walkers Free F Night King Night Mance Rayder Ho tch us a e W Ta tʹs Tormund rg h ar ig ye N Alliser Thorne n Jeor Mormont se u Drogo o nt H o m r Osha o Ygri�e M Jorah Mormont Samwell Tarly Rickard Stark Olly Rhaegar Targaryen Rhaella Targaryen Brandon Stark Aerys II Targaryen Viserys Targaryen Jon Snow H o Varys D u a s y e Eddard Stark Daenerys Targaryen n e Ghost Missandei H Viserion Rhaegal Drogon o Grey Worm u Arthur Dayne s e M Robb Stark a r t e Elia Martell l l k r a t S Sansa Stark Oberyn Martell e s Grey Wind u o H S a Arya Stark Lady n d S n Nymeria Sand a k Nymeria e Bran Stark Obara Sand s Tyene Sand Summer Ellaria Sand Rickon Stark Shaggydog H o Catelyn Stark u s Margaery Tyrell e T Lyanna Stark y Olenna Tyrell r e l l Benjen Stark Melisandre Renly Baratheon Shireen Baratheon Howland Reed Meera Reed H o S7 Tommen Baratheon u Jojen Reed Stannis Baratheon s e Myrcella Baratheon R e e d S6 Joffrey Baratheon n o e h t a r Gendry a B Yara Greyjoy S5 Balon Greyjoy e Theon Greyjoy s u o H S4 Robert Baratheon H Podrick Payne o Brienne of Tarth u s e G Euron Greyjoy r S3 e y Aeron Greyjoy jo y Ramsay Bolton Lancel Lannister S2 Robin Arryn e Roose Bolton s u o th Ilyn Payne r S1 H a H T o u High Sparrow se B 297 o e l Tyrion Lannister n t Shae y o a n P Jon Arryn Kevan Lannister Lysa Arryn se u Petyr Baelish Jaime Lannister o Cersei Lannister Gregor Clegane H Edmure Tully Thoros H Tywin Lannister ou Beric Dondarrion s se ow A rr rr a yn Sp Sandor Clegane Ho Walder Frey use Tu r lly H 257 iste ous ann e se L Fr Hou ey Brot herhood use W Ho ithout Banners Clegane A llegian ces Subordinate Sovereign s Lover ip h Master s Direwolf n Lover o i Dragon t a l e Spouse R Victim Spouse s Mercy killer l l i Legend Victim K Sibling Killer Sibling Resurrected Deceased Child Season Parent Child F Alive a m i li es Year s ne eli Lif. -

2021 Rittenhouse Game of Thrones Iron Anniversary Series 1

2021 Game of Thrones Iron Ann. S1 Inscription Variations Beckett.com/News Aimee Richardson as Myrcella Baratheon Avoid Dragons PR: 25-50 Game of Thrones PR: 25-50 Hear Me Roar PR: 100-150 House Baratheon PR: 25-50 House Baratheon (or Lannister?) PR: 25-50 I'm a princess! PR: 25-50 Joffrey's Sister PR: 25-50 Myrcella Baratheon PR: 100-150 Ours is the Fury PR: 50-75 Princess for Hire PR: 50-75 Princess Myrcella PR: 50-75 Secretly a Lannister! PR: 25-50 Tommen's sister PR: 25-50 Alfie Allen as Theon Greyjoy Any last words? PR: 50-75 Do the Right Thing PR: 25-50 Game of Thrones PR: 50-75 HOUSE GREYJOY PR: 25-50 I chose wrong PR: 10-25 I did terrible things PR: 25-50 IRONBORN PR: 25-50 It can always be worse PR: 10-25 Pay the iron price! PR: 10-25 REEK PR: 25-50 Theon Greyjoy PR: 50-75 There is no escape PR: 10-25 Amrita Acharia as Irri Doreah Betrayed Me PR: 25-50 dothraki rule PR: 25-50 dothraki Translator PR: 25-50 Game of Thrones PR: 10-25 handmaiden PR: 50-75 I serve Khaleesi PR: 10-25 Irri PR: 100-150 it is known PR: 50-75 She is a Khaleesi PR: 25-50 The Great Stallion PR: 25-50 Ania Bukstein as Kinvara Game of Thrones PR: 25-50 High Pristess PR: 10-25 Kinvara (cursive) PR: 50-75 Kinvara (print) PR: 150-200 1 2021 Game of Thrones Iron Ann.