The Origins and Development of the Labour Movement in West London 1918-1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Runmed March 2001 Bulletin

No. 325 MARCH Bulletin 2001 RUNNYMEDE’S QUARTERLY Challenge and Change Since the release of our Commission’s report, The Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain, Runnymede has been living in interesting times. Substantial and ongoing media coverage – from the enlivening to the repellent – has fueled the debate.Though the press has focused on some issues at the expense of others, numerous events organised to broaden the discussion continue to explore the Report’s substantial content, and international interest has been awakened. At such a moment, it is a great external organisations wishing to on cultural diversity in the honour for me to be taking over the arrange events. workplace, Moving on up? Racial Michelynn Directorship of Runnymede.The 3. A National Conference to Equality and the Corporate Agenda, a Laflèche, Director of the challenges for the next three years mark the first anniversary of the Study of FTSE-100 Companies,in Runnymede Trust are a stimulus for me and our Report’s launch is being arranged for collaboration with Schneider~Ross. exceptional team, and I am facing the final quarter of 2001, in which This publication continues to be in them with enthusiasm and optimism. we will review the responses to the high demand and follow-up work to Runnymede’s work programme Report over its first year. A new that programme is now in already reflects the key issues and element will be introduced at this development for launching in 2001. recommendations raised in the stage – how to move the debate Another key programme for Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain Report, beyond the United Kingdom to the Runnymede is our coverage of for which a full dissemination level of the European Union. -

A31 Note: Gunnersbury Station Does Not Have OWER H91 E D

C R S D E A U T S A VE N E R A N B B D L W Based on Bartholomews mapping. Reproduced by permission of S R E i N U st A R O HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., Bishopbriggs, Glasgow. 2013Y ri E E A Y c W R A t D A AD www.bartholomewmaps.com N C R 272 O Y V L D R i TO T AM 272 OL E H D BB N n A O CAN CO By Train e N Digital Cartography by Pindar Creative N U L E n w i a L Getting to BSI m lk 5 i AVE 1 ng N A Acton0- t V 1 im • The London Overground runs between E t e e LD ROAD B491 D N a SOUTHFIE E Y Town fr R Address: Chiswick Tower, U imR B o B E U O 440 m Richmond and Stratford stopping at Travel to E x L D B A R o S L AD R r O E RO O s 389 Chiswick High Road, London, W4 4AL Y R G R E p EY L i SPELDHUR Gunnersbury. ID ST R A R R t RO M p NR B E A O N e D NU O H L A A UB E LL C D GS BO T Y British Standards 1 R E RSET E E 9 N L SOM T N All visitors must enter the building through F 44 U N H • The ‘Hounslow Loop’ has stations at G SOUTH ROAD BEDFORD B E3 E B E R the main entrance on Chiswick High Road O Kew Bridge, Richmond, Weybridge, N O L PARK D Institution S ACTON L A A A D N E O R E O D and report to Reception on arrival. -

Jacob (Jack) Gaster Archive (GASTER)

Jacob (Jack) Gaster Archive (GASTER) ©Bishopsgate Institute Catalogued by Zoe Darani and Barbara Vasey 2008, 2016. 1 Table of Contents Ref Title Page GASTER/1 London County Council Papers 6 GASTER/2 Press Cuttings 17 GASTER/3 Miscellaneous 19 GASTER/4 Political Papers 22 GASTER/5 Personal Papers 35 2 GASTER Gaster, Jacob (Jack) (1907-2007) 1977-1999 Name of Creator: Gaster, Jacob (Jack) (1907-2007) lawyer, civil rights campaigner and communist Extent: 6 Boxes Administrative/Biographical History: Jacob (Jack) Gaster was the twelfth of the thirteen children born to Moses Gaster, the Chief Rabbi of the Sephardic Community of England, and his wife, Leah (daughter of Michael Friedlander, Principal of Jews’ College). Rumanian by birth, Moses Gaster was a distinguished scholar and linguist. He was also keenly active in early twentieth century Zionist politics. Never attracted by Zionism and from 1946, a supporter of a “one state” solution to Israel/Palestine, Gaster still never broke with his father, merely with his father’s ideas, becoming acutely aware of working class politics (and conditions of life) during the General Strike in 1926. While his favourite brother, Francis actually worked as a blackleg bus driver, Jack Gaster sided with the strikers. It was at this time that he joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP), then headed by James Maxton. Despite his admiration for Maxton (who remained with the ILP), as a leading member of the Revolutionary Policy Committee (RPC) within the ILP, Jack Gaster led the 1935 “resignation en masse”, taking a substantial group within the ILP with him to join the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). -

Radical Nostalgia, Progressive Patriotism and Labour's 'English Problem'

Radical nostalgia, progressive patriotism and Labour©s ©English problem© Article (Accepted Version) Robinson, Emily (2016) Radical nostalgia, progressive patriotism and Labour's 'English problem'. Political Studies Review, 14 (3). pp. 378-387. ISSN 1478-9299 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/61679/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Author’s Post-Print Copy Radical nostalgia, progressive patriotism and Labour's 'English problem' Emily Robinson, University of Sussex ABSTRACT ‘Progressive patriots’ have long argued that Englishness can form the basis of a transformative political project, whether based on an historic tradition of resistance to state power or an open and cosmopolitan identity. -

Borough Wide Ealing Area Improvements

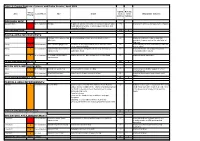

Table 2: Capital Projects - Leisure and Parks Service, April 2009 Capital Revenue Officer Area Lead Officer Title Details Costs Costs What will be delivered Priority (£000's) (£000s) BOROUGH WIDE Borough Wide 1 Steve Marshall Furniture Replace all old style bins with new standard (approx. 200). 173 Improved cleanliness and appearance of parks Install additional 50 bins. (Total includes installation and removal of old bins) BOROUGH WIDE TOTAL 173 0 EALING AREA IMPROVEMENTS: Ealing 1 Steve Marshall Pitshanger Park pavilion and Demolish buildings (tender process about to start) 50 Improved aesthetics, reduced ASB and toilet block provision of space required for installation of Superloo Ealing 1 Steve Marshall Dean Gardens playground Extension of the playground as part of the town centre 20 Improved play facilities; matched by £20k from regeneration programme Regeneration Ealing 2 Steve Marshall Lammas Park new entrance Review of layout and paths with the new entrance on 15 Improved access, visual appearance and improvements Culmington Road consultation with residents Ealing 2 Steve Marshall Cleveland Park boundary Improvement of the park railings on Cleveland Road 15 Improved visual appearance improvements EALING AREA IMPROVEMENTS TOTAL 100 0 ACTON AREA IMPROVEMENTS: Acton 2 Steve Marshall Bollo Brook sports field Works to pitch to include levelling 15 Improved sports facility, support of school (Berrymede JS) Acton 2 Steve Marshall Acton Park boundary Improvements to park boundary railings 20 Improved visual appeal and enhance park safety ACTON AREA IMPROVEMENTS TOTAL 35 0 PERIVALE AREA IMPROVEMENTS: Perivale 2 Julia Robertson Perivale Park Outdoor Gym at Perivale Park Athletics Track-Build an 20 Build an outdoor gym to compliment the existing outdoor gym to compliment the existing small indoor gym at small indoor gym at the Track to alleviate some the Track to alleviate some of the pressures on usage of the pressures on usage during opening during opening hours. -

Parliamentary Questions As Instruments of Substantive Representation: Visible Minorities in the UK House of Commons, 2005-2010

Parliamentary Questions as Instruments of Substantive Representation: Visible Minorities in the UK House of Commons, 2005-2010 Thomas Saalfeld University of Bamberg Faculty of Social Sciences, Economics and Business Administration Feldkirchenstr. 21 96045 Bamberg Germany Email [email protected] Abstract: Little is known about the parliamentary behaviour of immigrant-origin legislators in European democracies. Much of the literature is normative, theoretical and speculative. Where it exists, empirical scholarship tends to be based on qualitative interviews, anecdotal evidence and generalisations based on very few cases. Whether the growing descriptive representation of minority-ethnic legislators has any implications for the quality of substantive representation, remains an open question. Parliamentary questions can be used as a valid and reliable indicator of substantive representation in democratic parliaments. This study is based on a new data set of over 16,000 parliamentary questions tabled by 50 British backbench Members of Parliament (MPs) in the 2005-2010 Parliament. It includes the 16 immigrant-origin MPs with a ‘visible- minority’ background. The most innovative feature of its research design is the use of a matching contrast group of non-minority MPs. Based on a series of multivariate models, it is found that all British MPs sampled for this study – irrespective of their ethnic status – respond to electoral incentives arising from the socio-demographic composition of their constituencies: Minority and non-minority MPs alike ask more questions relating to minority concerns, if they represent constituencies with a high share of non-White residents. Controlling for that general effect, however, MPs with a visible-minority status ask significantly more questions about ethnic diversity and equality issues. -

30Hr Childcare: Analysis of Potential Demand and Sufficiency in Ealing

30hr Childcare: Analysis of potential demand and sufficiency in Ealing. Summer 2016 Introduction: Calculating the number of eligible children in each Ward of the borough The methodology utilised by the DfE to predict the number of eligible children in the borough cannot be replicated at Ward level (refer to page 14: Appendix 1 for DfE methodology) Therefore the calculations for the borough have been calculated utilising the most recent data at Ward level concerning the proportions of parents working, the estimates of 3& 4 year population and the number of those 4yr old ineligible as they are attending school. The graph below illustrates the predicted lower and upper estimates for eligible 3&4 year olds for each Ward Page 1 of 15 Executive Summary The 30hr eligibility criteria related to employment, income and the number of children aged 4 years attending reception class (who are ineligible for the funding) makes it much more likely that eligible children will be located in Wards with higher levels of employment and income (potentially up to a joint household income of £199,998) and lower numbers of children aged 4years in reception class. Although the 30hr. childcare programme may become an incentive to work in the future, in terms of the immediate capital bid, the data points to investment in areas which are quite different than the original proposal, which targeted the 5 wards within the Southall area. The 5 Southall Wards are estimated to have the fewest number of eligible children for the 30hr programme. The top 5 Wards estimated to have the highest number of eligible children are amongst the least employment and income deprived Wards in Ealing with the lowest numbers of children affected by income deprivation. -

The Theological Socialism of the Labour Church

‘SO PECULIARLY ITS OWN’ THE THEOLOGICAL SOCIALISM OF THE LABOUR CHURCH by NEIL WHARRIER JOHNSON A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The thesis argues that the most distinctive feature of the Labour Church was Theological Socialism. For its founder, John Trevor, Theological Socialism was the literal Religion of Socialism, a post-Christian prophecy announcing the dawn of a new utopian era explained in terms of the Kingdom of God on earth; for members of the Labour Church, who are referred to throughout the thesis as Theological Socialists, Theological Socialism was an inclusive message about God working through the Labour movement. By focussing on Theological Socialism the thesis challenges the historiography and reappraises the significance of the Labour -

Planning Committee 31/03/2010 Schedule Item:05

Planning Committee 31/03/2010 Schedule Item:05 Ref: P/2009/4361 Address: 54 MEADVALE ROAD EALING W5 1NR Ward: Cleveland Proposal: Single storey part rear infill extension Drawing numbers: 54MR/10 rev A and 54MR/11 rev A (all received 02/03/2010) Type of Application: Full Application Application Received: 21/12/2009 Revised: 02/03/2010 Report by: Beth Eite 1. Summary of Site and Proposal: The application site comprises a two storey semi-detached property which has a hipped roof with sproketed eaves which overhang the main walls. The property has a two storey outrigger with a roof pitch that matches the main roof, this outrigger spans the boundary with the adjoining semi-detached house and is shared between the two properties. To the rear of the outrigger of the subject property is a single storey extension. This has a monopitch roof which sits directly below the sill of the first floor window. The brickwork for this extension does not match the original brick on the main house. The property is located on the northern side of Meadvale Road which backs on to Brentham Sports Ground. To the western side of the property is an attached single storey garage which has a pitch roof. Permission has recently been granted to rebuild this garage with a flat roof up to a height of 2.7m. The property is situated within the Brentham Garden Estate which is a conservation area covered by an article 4 direction that restricts most types of development and alterations to properties. Brentham Garden Suburb in Ealing, west London, is no ordinary group of 620 houses. -

Harry Pollitt, Rhondda East and the Cold War Collapse of the British Communist Electorate

The University of Manchester Research Harry Pollitt, Rhondda East and the Cold War collapse of the British communist electorate Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K. (2011). Harry Pollitt, Rhondda East and the Cold War collapse of the British communist electorate. Llafur, 10(4), 16-31. Published in: Llafur Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:30. Sep. 2021 Harry Pollitt, Rhondda East and the Cold War collapse of the British communist electorate Kevin Morgan Visiting Britain a few weeks before the 1945 general election, the French communist Marcel Cachin summarised one conversation: ‘H. Pollitt: 22 candidates in England, 6 MPs anticipated.’1 Pollitt, secretary of the British communist party (CPGB), was not for the first time overly optimistic: of the twenty-one communist candidates who went to the poll, only two were returned to parliament. -

Buses from Ealing Common

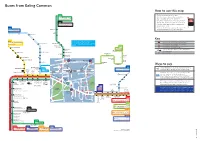

Buses from Ealing Common 483 towards Harrow Bus Station for Harrow-on-the-Hill Buses from Ealing Commonfrom stops EM, EP, ER N83 towards Golders Green from stops EM, EP, ER N7 483 towards Northolt Alperton towards Harrow Bus Station for Harrow-on-the-Hill from stops EH, EJ, EK, EL from stops EM, EP, ER 483 N83 N7 Argyle Road N83 towards Golders Green from stops EM, EP, ER N7 towardsE11 Northolt Alperton Route 112 towards North Finchley does not call at any bus stops within the central map. fromtowards stops Greenford EH, EJ, EK Broadway, EL Pitshanger Lane Ealing Road Route 112 towards North Finchley can be boarded from stops EW 483 at stops on Hanger Lane (Hillcrest Road, Station or N83 N7 Argyle Road Hanger Lane Gyratory). Quill Street 218 Castle Bar Park from stops Hanger Lane EA, ED, EE, EF Gyratory North Acton Woodeld Road Hanger Lane E11 Copley Close Route 112 towards North Finchley does not call 483 N83 at any bus stops within the central map. Northelds towards Greenford Broadway Road Pitshanger Lane Ealing Road Hanger Lane Route 112 towards North Finchley can be boarded Victoria from stops EW at stops on Hanger Lane (Hillcrest Road, Station or E11 Hillcrest Road 218 Road Browning Avenue N7 Hanger Lane Gyratory). 218 Quill Street Eastelds 218 Castle Bar Park Drayton Green Road North Ealing West Acton from stops Gypsy Hangerq Lane EA, ED, EE, EF Corner Eaton Rise IVE STATION APPROA GyratoryEEN’S DR CH e Westelds QU Road North Acton Woodeld Road ROAD Hanger Lane AD Copley Close 112 ELEY RO Noel Road MAD Northelds 483 N83‰ L Road -

1986 Peace Through Non-Alignment: the Case for British Withdrawal from NATO

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified 1986 Peace Through Non-Alignment: The case for British withdrawal from NATO Citation: “Peace Through Non-Alignment: The case for British withdrawal from NATO,” 1986, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Ben Lowe, Published by Verso, sponsored by The Campaign Group of Labor MP's, The Socialist Society, and the Campaign for Non-Alignment, 1986. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/110192 Summary: Pamphlet arguing for British withdrawal from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. It examines the origins of NATO, its role in U.S. foreign policy, its nuclear strategies, and its effect on British politics and national security. Original Language: English Contents: Scan of Original Document Ben Lowe is author of a book on NATO published in Spain as part of the campaign for Spanish withdrawal during the referendum of March 1986, La Cara Ocuita de fa OTAN; a contributor to Mad Dogs edited by Edward Thompson and Mary Kaldor; and a member of the Socialist Society, which has provided financial and research support for this pamphlet. Ben Lowe Peace through Non-Alignlllent The Case Against British Membership of NATO The Campaign Group of Labour MPs welcomes the publication of this pamphlet and believes that the arguments it contains are worthy of serious consideration. VERSO Thn Il11prlnt 01 New Left Books Contents First published 1986 Verso Editions & NLB F'oreword by Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn 15 Greek St, London WI Ben Lowe 1986 Introduction 1 ISBN 086091882 Typeset by Red Lion Setters 1. NATO and the Post-War World 3 86 Riversdale Road, N5 Printed by Wernheim Printers Forster Rd N17 Origins of the Alliance 3 America's Global Order 5 NATO's Nuclear Strategies 7 A Soviet Threat? 9 NA TO and British Politics 11 Britain's Strategic Role 15 Star Wars and Tension in NA TO 17 America and Europe's Future 19 2.