CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE the OBOE and ITS PLACE in MUSIC HISTORY a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

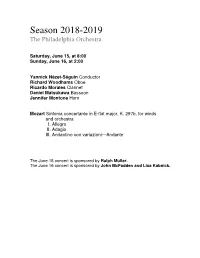

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

Leihmaterial Bote & Bock

Leihmaterial Bote & Bock - Stand: November 2015 - Komponist / Titel Instrumentation Komp. / Dauer Aa, Michel van der 2 After Life B 2S,M,A,2Ba; 2005-06/ 95' Oper nach dem Film von Hirokazu Kore-Eda 0.1.1.BKl.0-0.1.0.1-Org(=Cemb)-Str(3.3.3.2.2); 2009 elektr Soundtrack; Videoprojektionen 1 The Book of DisquietB 1.0.1.1-0.1.0.0-Perc(1): 2008 75' Musiktheater für Schauspieler, Ensemble und Film Vib/Glsp/3Metallstücke/Cabasa/Maracas/Egg Shaker/ 4Chin.Tomt/grTr/Bambusglocken/Ratsche/Peitsche(mi)/ HlzBl(ti)/2Logdrum/Tri(ho)/2hgBe-4Vl.3Va.2Vc.Kb- Soundtrack(Laptop,1Spieler)-Film(2Bildschirme) 0 Here [enclosed] B 0.0.1.1-0.1.1.0-Perc(1)-Str(6.6.6.4.2)- 2003 17' für Kammerorchester und Soundtrack Soundtrack(Laptop, 1Spieler); Theaterobjekt K Here [in circles] B Kl.BKl.Trp-Perc(1)-Str(1.1.1.1.1); 2002 15' für Sopran und Ensemble kl Kassetten-Rekorder (z.B. Sony TCM-939) 0 Here [to be found]B 0.0.1.1-0.1.1.0-Perc(1)-Str(6.6.6.4.2)- 2001 18' für Sopran, Kammerorchester und Soundtrack Soundtrack(Laptop, 1 Spieler) Here Trilogy B 2001-03 50' siehe unter Here [enclosed], Here [in circles], Here [to be found] F Hysteresis B Fg-Trp-Perc(1)-Str*; Soundtrack(Laptop,1 Spieler); 2013 17' für Solo-Klarinette, Ensemble und Soundtrack *Streicher: 1.0.1.1.1 (alle vertärkt) oder 4.0.3.2.1 oder 6.0.5.4.2; Kb mit tiefer C-Saite 2 Imprint B 2Ob-Cemb-Str(4.4.3.2.1); 2005 14' für Barock-Orchester Portativ-Orgel zu spielen vom Solo-Violinisten; Historische Instrumente (415 Hz Stimmung) oder moderne Instrumente in Barock-Manier gespielt 1 Mask B 1.0.1.0-1.1.1.0-Perc(1)-Str(1.1.1.1.1)- -

Tuba Syllabus / 2003 Edition

74058_TAP_SyllabusCovers_ART_Layout 1 2019-12-10 10:56 AM Page 36 Tuba SYLLABUS / 2003 EDITION SHIN SUGINO SHIN Message from the President The mission of The Royal Conservatory—to develop human potential through leadership in music and the arts—is based on the conviction that music and the arts are humanity’s greatest means to achieve personal growth and social cohesion. Since 1886 The Royal Conservatory has realized this mission by developing a structured system consisting of curriculum and assessment that fosters participation in music making and creative expression by millions of people. We believe that the curriculum at the core of our system is the finest in the world today. In order to ensure the quality, relevance, and effectiveness of our curriculum, we engage in an ongoing process of revitalization, which elicits the input of hundreds of leading teachers. The award-winning publications that support the use of the curriculum offer the widest selection of carefully selected and graded materials at all levels. Certificates and Diplomas from The Royal Conservatory of Music attained through examinations represent the gold standard in music education. The strength of the curriculum and assessment structure is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of outstanding musicians and teachers from Canada, the United States, and abroad who have been chosen for their experience, skill, and professionalism. An acclaimed adjudicator certification program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in helping all people to open critical windows for reflection, to unleash their creativity, and to make deeper connections with others. -

Music in the Baroque Period

MUSIC A.D. 450–1995 BY MARK AMMONS, D.M.A. COPYRIGHT © 1995 Mark Twain Media, Inc. ISBN 978-1-58037-976-2 Printing No. 1890-EB Mark Twain Media, Inc., Publishers Distributed by Carson-Dellosa Publishing LLC The purchase of this book entitles the buyer to reproduce the student pages for classroom use only. Other permissions may be obtained by writing Mark Twain Media, Inc., Publishers. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Music: A.D. 450–1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................................................................................... iii Time Line ......................................................................................................................... iv Music in the Middle Ages ..................................................................................................1 Pope Gregory I and the Dove ...........................................................................................4 Leonin and Perotin Go to School ......................................................................................6 Troubadours, Trouvères, and Jongleurs............................................................................9 “New Art” vs. “Old Art” .....................................................................................................11 Music in the Renaissance ...............................................................................................13 Josquin: The Man, the Myth, the Great...........................................................................15 -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Elliott Carter Works List

W O R K S Triple Duo (1982–83) Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation Basel ORCHESTRA Adagio tenebroso (1994) ............................................................ 20’ (H) 3(II, III=picc).2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(4):BD/ 4bongos/glsp/4tpl.bl/cowbells/vib/2susp.cym/2tom-t/2wdbl/SD/xyl/ tam-t/marimba/wood drum/2metal block-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Allegro scorrevole (1996) ........................................................... 11’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-perc(4):timp/glsp/xyl/vib/ 4bongos/SD/2tom-t/wdbl/3susp.cym/2cowbells/guiro/2metal blocks/ 4tpl.bl/BD/marimba-harp-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Anniversary (1989) ....................................................................... 6’ (H) 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2):vib/marimba/xyl/ 3susp.cym-pft(=cel)-strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Boston Concerto (2002) .............................................................. 19’ (H) 3(II,III=picc).2.corA.3(III=bcl).3(III=dbn)-4.3.3.1-perc(3):I=xyl/vib/log dr/4bongos/high SD/susp.cym/wood chime; II=marimba/log dr/ 4tpl.bl/2cowbells/susp.cym; III=BD/tom-t/4wdbls/guiro/susp.cym/ maracas/med SD-harp-pft-strings A Celebration of Some 100 x 150 Notes (1986) ....................... 3’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(1):glsp/vib-pft(=cel)- strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Concerto for Orchestra (1969) .................................................. -

JS BACH (1685-1750): Violin and Oboe Concertos

BACH 703 - J. S. BACH (1685-1750) : Violin and Oboe Concertos Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21 st , l685, the son of Johann Ambrosius, Court Trumpeter for the Duke of Eisenach and Director of the Musicians of the town of Eisenach in Thuringia. For many years, members of the Bach family throughout Thuringia had held positions such as organists, town instrumentalists, or Cantors, and the family name enjoyed a wide reputation for musical talent. By the year 1703, 18-year-old Johann Sebastian had taken up his first professional position: that of Organist at the small town of Arnstadt. Then, in 1706 he heard that the Organist to the town of Mülhausen had died. He applied for the post and was accepted on very favorable terms. However, a religious controversy arose in Mülhausen between the Orthodox Lutherans, who were lovers of music, and the Pietists, who were strict puritans and distrusted art. So it was that Bach again looked around for more promising possibilities. The Duke of Weimar offered him a post among his Court chamber musicians, and on June 25, 1708, Bach sent in his letter of resignation to the authorities at Mülhausen. The Weimar years were a happy and creative time for Bach…. until in 1717 a feud broke out between the Duke of Weimar at the 'Wilhelmsburg' household and his nephew Ernst August at the 'Rote Schloss’. Added to this, the incumbent Capellmeister died, and Bach was passed over for the post in favor of the late Capellmeister's mediocre son. Bach was bitterly disappointed, for he had lately been doing most of the Capellmeister's work, and had confidently expected to be given the post. -

Unifying Elements of John Corigliano's

UNIFYING ELEMENTS OF JOHN CORIGLIANO'S ETUDE FANTASY By JANINA KUZMAS Undergraduate Diploma with honors, Sumgait College of Music, USSR, 1985 B. Mus., with the highest honors, Vilnius Conservatory, Lithuania, 1991 Performance Certificate, Lithuanian Academy of Music, 1993 M. Mus., Bowling Green State University, USA, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Music We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 2002 © Janina Kuzmas 2002 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. ~':<c It CC L Department of III -! ' The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date J/difc-L DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT John Corigliano's Etude Fantasy (1976) is a significant and challenging addition to the late twentieth century piano repertoire. A large-scale work, it occupies a particularly important place in the composer's output of music for piano. The remarkable variety of genres, styles, forms, and techniques in Corigliano's oeuvre as a whole is also evident in his piano music. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

The Blake Collection in Memory of Nancy M

The Blake Collection In Memory of Nancy M. Blake BELLINI’S NORMA featuring CECILIA BARTOLI This tragic opera is set in Roman-occupied, first-century Gaul, features a title character, who although a Druid priestess, is in many ways a modern woman. Norma has secretly taken the Roman proconsul Pollione as her lover and had two children with him. Political and personal crises arise when the locals turn against the occupiers and Pollione turns to a new paramour. Norma “is a role with emotions ranging from haughty and demanding, to desperately passionate, to vengeful and defiant. And the singer must convey all of this while confronting some of the most vocally challenging music ever composed. And if that weren't intimidating enough for any singer, Norma and its composer have become almost synonymous with the specific and notoriously torturous style of opera known as bel canto — literally, ‘beautiful singing’” (“Love Among the Druids: Bellini's Norma,” NPR World of Opera, May 16, 2008). And Bartoli, one of the greatest living opera divas, is up to the challenges the role brings. (New York Public Radio’s WQXR’s “OperaVore” declared that “Bartoli is Fierce and Mercurial in Bellini's Norma,” Marion Lignana Rosenberg, June 09, 2013.) If you’re already a fan of this opera, you’ve no doubt heard a recording spotlighting the great soprano Maria Callas (and we have such a recording, too), but as the notes with the Bartoli recording point out, “The role of Norma was written for Giuditta Pasta, who sang what today’s listeners would consider to be mezzo-soprano roles,” making Bartoli more appropriate than Callas as Norma. -

An Analysis and Performance Considerations for John

AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN (Under the Direction of D. RAY MCCLELLAN) ABSTRACT John Harbison is an award-winning and prolific American composer. He has written for almost every conceivable genre of concert performance with styles ranging from jazz to pre-classical forms. The focus of this study, his Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, was premiered in 1985 as a product of a Consortium Commission awarded by the National Endowment of the Arts. The initial discussions for the composition were with oboist Sara Bloom and clarinetist David Shifrin. Harbison’s Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings allows the clarinet to finally be introduced to the concerto grosso texture of the Baroque period, for which it was born too late. This document includes biographical information on John Harbison including his life and career, compositional style, and compositional output. It also contains a brief history of the Baroque concerto grosso and how it relates to the Harbison concerto. There is a detailed set-class analysis of each movement and information on performance considerations. The two performers as well as the composer were interviewed to discuss the commission, premieres, and theoretical/performance considerations for the concerto. INDEX WORDS: John Harbison, Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, clarinet concerto, oboe concerto, Baroque concerto grosso, analysis and performance AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN B.M., Tennessee Technological University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Katherine Belvin All Rights Reserved AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN Major Professor: D. -

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter SUN / OCT 21 / 11:00 AM Michele Zukovsky Robert deMaine CLARINET CELLO Robert Davidovici Kevin Fitz-Gerald VIOLIN PIANO There will be no intermission. Please join us after the performance for refreshments and a conversation with the performers. PROGRAM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Trio in B-flat major, Op. 11 I. Allegro con brio II. Adagio III. Tema: Pria ch’io l’impegno. Allegretto Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) Quartet for the End of Time (1941) I. Liturgie de cristal (“Crystal liturgy”) II. Vocalise, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Vocalise, for the Angel who announces the end of time”) III. Abîme des oiseau (“Abyss of birds”) IV. Intermède (“Interlude”) V. Louange à l'Éternité de Jésus (“Praise to the eternity of Jesus”) VI. Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes (“Dance of fury, for the seven trumpets”) VII. Fouillis d'arcs-en-ciel, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Tangle of rainbows, for the Angel who announces the end of time) VIII. Louange à l'Immortalité de Jésus (“Praise to the immortality of Jesus”) This series made possible by a generous gift from Barbara Herman. PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE 20 ABOUT THE ARTISTS MICHELE ZUKOVSKY, clarinet, is an also produced recordings of several the Australian National University. American clarinetist and longest live performances by Zukovsky, The Montréal La Presse said that, serving member of the Los Angeles including the aforementioned Williams “Robert Davidovici is a born violinist Philharmonic Orchestra, serving Clarinet Concerto. Alongside her in the most complete sense of from 1961 at the age of 18 until her busy performing schedule, Zukovsky the word.” In October 2013, he retirement on December 20, 2015.