Tomasso Brothers Fine Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michelangelo's Locations

1 3 4 He also adds the central balcony and the pope’s Michelangelo modifies the facades of Palazzo dei The project was completed by Tiberio Calcagni Cupola and Basilica di San Pietro Cappella Sistina Cappella Paolina crest, surmounted by the keys and tiara, on the Conservatori by adding a portico, and Palazzo and Giacomo Della Porta. The brothers Piazza San Pietro Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano facade. Michelangelo also plans a bridge across Senatorio with a staircase leading straight to the Guido Ascanio and Alessandro Sforza, who the Tiber that connects the Palace with villa Chigi first floor. He then builds Palazzo Nuovo giving commissioned the work, are buried in the two The long lasting works to build Saint Peter’s Basilica The chapel, dedicated to the Assumption, was Few steps from the Sistine Chapel, in the heart of (Farnesina). The work was never completed due a slightly trapezoidal shape to the square and big side niches of the chapel. Its elliptical-shaped as we know it today, started at the beginning of built on the upper floor of a fortified area of the Apostolic Palaces, is the Chapel of Saints Peter to the high costs, only a first part remains, known plans the marble basement in the middle of it, space with its sail vaults and its domes supported the XVI century, at the behest of Julius II, whose Vatican Apostolic Palace, under pope Sixtus and Paul also known as Pauline Chapel, which is as Arco dei Farnesi, along the beautiful Via Giulia. -

On the Spiritual Matter of Art Curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi 17 October 2019 – 8 March 2020

on the spiritual matter of art curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi 17 October 2019 – 8 March 2020 JOHN ARMLEDER | MATILDE CASSANI | FRANCESCO CLEMENTE | ENZO CUCCHI | ELISABETTA DI MAGGIO | JIMMIE DURHAM | HARIS EPAMINONDA | HASSAN KHAN | KIMSOOJA | ABDOULAYE KONATÉ | VICTOR MAN | SHIRIN NESHAT | YOKO ONO | MICHAL ROVNER | REMO SALVADORI | TOMÁS SARACENO | SEAN SCULLY | JEREMY SHAW | NAMSAL SIEDLECKI with loans from: Vatican Museums | National Roman Museum | National Etruscan Museum - Villa Giulia | Capitoline Museums dedicated to Lea Mattarella www.maxxi.art #spiritualealMAXXI Rome, 16 October 2019. What does it mean today to talk about spirituality? Where does spirituality fit into a world dominated by a digital and technological culture and an ultra-deterministic mentality? Is there still a spiritual dimension underpinning the demands of art? In order to reflect on these and other questions MAXXI, the National Museum of XXI Century Arts, is bringing together a number of leading figures from the contemporary art scene in the major group show on the spiritual matter of art, strongly supported by the President of the Fondazione MAXXI Giovanna Melandri and curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi (from 17 October 2019 to 8 March 2020). Main partner Enel, which for the period of the exhibition is supporting the initiative Enel Tuesdays with a special ticket price reduction every Tuesday. Sponsor Inwit. on the spiritual matter of art is a project that investigates the issue of the spiritual through the lens of contemporary art and, at the same time, that of the ancient history of Rome. In a layout offering diverse possible paths, the exhibition features the works of 19 artists, leading names on the international scene from very different backgrounds and cultures. -

AH/CU/MU 340 CITIES AS LIVING MUSEUMS IES Abroad Paris BIA – Rome – Madrid

AH/CU/MU 340 CITIES AS LIVING MUSEUMS IES Abroad Paris BIA – Rome – Madrid COURSE DESCRIPTION: Through an interdisciplinary approach, students will be able to appreciate how throughout their long histories the cities of Paris, Rome and Madrid have developed around the central idea of cultural heritage and patrimony. The program offers a unique opportunity to examine how art, architecture and monuments have at different times and in different ways affected urban development, life and culture in three European capitals. The complex relationship between artistic development, politics, economics and ideology will be analyzed in detail by considering how museums, monuments and archaeological sites developed in different periods of modern European history. The course considers the history of art collections, museum centers and attitudes towards antiquities, monuments and archaeological sites. Special attention is given to how underlying concepts in conservation and preservation theory and cultural management have evolved through time. CREDITS: 3 LANGUAGE OF INSTRUCTION: English PREREQUISITES: None ADDITIONAL COST: None METHOD OF PRESENTATION: Lectures, class discussions, course-related trips to monuments, museums and archaeological sites REQUIRED WORK AND FORMS OF ASSESSMENT: Paris Portion: 25% • Class participation: 10% • Daily comment on visit (Journal): 40% • Paris City Exam: 50% Rome Portion: 25% • Class participation: 10% • Daily comment on visit (Journal): 40% • Rome City Exam: 50% Madrid Portion: 25% • Class participation: 10% • Daily comment on visit (Journal): 40% • Madrid City Exam: 50% Cumulative Final Paper: 25% The final paper will be a cumulative, take-home essay. It should be turned into Moodle. Work will be assessed on the basis of students’ visual observations, mastery of course material, and critical interventions. -

Roma Aeterna I: Ancient and Medieval Rome

Dr. Max Grossman Art History 3399 ACCENT Rome Study Abroad Center Summer 2020 [email protected] CRN# ????? Cell +39 340-4586937 T/Th 9:00am-1:00pm Roma Aeterna I: Ancient and Medieval Rome Art History 3399 is a specialized upper-division course on the urbanism, architecture, sculpture and painting of the city of Rome from the founding of the city in 753 BC through 1420. Through its artistic treasures, we will trace the rise of Rome from an obscure village to the largest and most populous metropolis on earth, to its medieval transformation into a modest community of less than thirty thousand inhabitants—from the political and administrative capital of the Roman Empire to the spiritual epicenter of medieval Europe. The first part of the course will cover the ancient period (up until 476 AD) and will focus on the artistic patronage of the Roman state and its leading citizens, and on the historic, social and political context of the artworks they produced. We will investigate the use of art for propagandistic and ideological purposes on the part of the emperors and their families, and on the stylistic and iconographic trends in the capital city. Moreover, we will explore what Roman artworks reveal about the complex interconnections among social classes, the relationship between Rome and its subject territories, the role of the military and the official state religion, and the emergence of Christianity and its rapid spread throughout the West. The second part of the course will treat the development of the Catholic Church and the papacy; the artistic patronage of popes, cardinals, monasteries, and seignorial families; the cult of relics and the institution of pilgrimage; and the careers of various masters, both local and foreign, who were active in the city. -

Top Attractions

TOP ROME ATTRACTIONS The Pantheon Constructed to honor all pagan gods, this best preserved temple of ancient Rome was rebuilt in the 2nd century AD by Emperor Hadrian, and to him much of the credit is due for the perfect dimensions: 141 feet high by 141 feet wide, with a vast dome that was the largest ever designed until the 20th century. The Vatican Though its population numbers only in the few hundreds, the Vatican—home base for the Catholic Church and the pope—makes up for them with the millions who visit each year. Embraced by the arms of the colonnades of St. Peter’s Square, they attend Papal Mass, marvel at St. Peter’s Basilica, and savor Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling. The Colosseum Legend has it that as long as the Colosseum stands, Rome will stand; and when Rome falls, so will the world. One of the seven wonders of the world, the mammoth amphitheater was begun by Emperor Vespasian and inaugurated by Titus in the year 80. For “the grandeur that was Rome,” this obstinate oval can’t be topped. Piazza Navona You couldn’t concoct a more Roman street scene: caffè and crowded tables at street level, coral- and rust-color houses above, most lined with wrought-iron balconies, street performers and artists and, at the center of this urban “living room,” Bernini’s spectacular Fountain of the Four Rivers and Borromini’s super-theatrical Sant’Agnese. Roman Forum This fabled labyrinth of ruins variously served as a political playground, a commerce mart, and a place where justice was dispensed during the days of the emperors (500 BC to 400 AD). -

Return International Airfares 3-4 Star Accommodation Professional

D aily Breakfast & dinner R eturn International Ai rfares 3 - 4 star accommodation P rDoafeilsys ional loca&l guide AiRrpeoturrtn T Irnatnesrfneartsi onal TrAiainrf atircekse ts 3-4 star accommodation Professional local guide Airport Transfers Train tickets Day 1: Melbourne - - Rome Departure from Melbourne, begin your journey of Italy. Day 2: Rome Arrive in Rom e , a C ity of 3 00 0 yea rs histor y. Italy ’ s capital is a sprawling , cosmopolitan city with nearly 3,000 years of globally influential art , architecture and culture on display . Ancient ruins such as the Roman Forum and the Colosseum evoke the power of the former Roman Empire .Up on arrival , your tour gu ide will meet you at the airport with the warmest greeting. Transfer to hotel . Day 3: Rome Empire Explore Rome after breakfast . You ’ll understand soon why it is defined an “open air mu seum”: as you walk aroun d the ci ty center, yo u’ll s ee the remains of it s glorio us past all around y ou, as you’re making a time travel back to the ancient Rome empire era. Visit C olosseum *, Arch of Constantine, Roman Forum*. Walk over to Venice Square and way up the Campidoglio Hill you will visit Capitoline Museums*. opened to the public since 1734.The Capitoline Museums are considered the first museum in the world including a large number of ancient Roman statues , inscriptions , and other artifacts ; a collection of medieval and Renaissance art ; and collections of jewels , coins and other items . Transfer ba c k to ho t el after din ner . -

Writing Rome

TRAVEL SEMINAR TO ROME JACKIE MURRAY “Writing Rome” (TX201) is a one-credit travel seminar that will introduce students to interdisciplinary perspectives on Rome. “All roads lead to Rome.” This maxim guides our study tour of the Eternal City. In “Writing Rome” students will travel to KAITLIN CURLEY ANDERS, Rome and compare the city constructed in texts with the city constructed of brick, concrete, marble, wood, and metal. This travel seminar will offer tours of the major ancient sites (includ- ing the Fora, the Palatine, the Colosseum, the Pantheon), as well as the Vatican, the major museums, churches and palazzi, Fascist monuments, the Jewish quarter and other locales ripe with the PHOTOS BY: DAN CURLEY, DAN CURLEY, PHOTOS BY: historical and cultural layering that is the city’s hallmark. In addi- OFF-CAMPUS STUDY & EXCHANGES tion, students will keep travel journals and produce a culminat- ing essay (or other written work) about their experiences on the tour, thereby continuing the tradition of writing Rome. WHY ROME? Rome is the Eternal City, a cradle of western culture, and the root of the English word “romance.” Founded on April 21, 753 BCE (or so tradition tells us), the city was the heart of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and today serves as the capitol of Italy. Creative Thought Matters Bustling, dense, layered, and sublime, Rome has withstood tyrants, invasions, disasters, and the ravages of the centuries. The Roman story is the story of civilization itself, with chapters ? written by citizens and foreigners alike. Now you are the author. COURSE SCHEDULE “Reading Rome,” the 3-credit lecture and discussion-based course, will be taught on the Skidmore College campus during the Spring 2011 semester. -

Best Sculpture in Rome"

"Best Sculpture in Rome" Créé par: Cityseeker 11 Emplacements marqués Wax Museum "History in Wax" Linked to the famed Madame Tussaud's in London, the Museo delle Cere recreates historical scenes such as Leonardo da Vinci painting the Mona Lisa surrounded by the Medici family and Machiavelli. Another scene shows Mussolini's last Cabinet meeting. There is of course a chamber of horrors with a garrotte, a gas chamber and an electric chair. The museum by _Pek_ was built to replicate similar buildings in London and Paris. It is a must visit if one is ever in the city in order to take home some unforgettable memories. +39 06 679 6482 Piazza dei Santi Apostoli 68/A, Rome Capitoline Museums "Le premier musée du monde" Les musées Capitoline sont dans deux palais qui se font face. Celui sur la gauche des marches de Michelange est le Nouveau Palais, qui abrite l'une des plus importantes collections de sculptures d'Europe. Il fut dessiné par Michelange et devint le premier musée public en 1734 sur l'ordre du pape Clément XII. L'autre palais, le Conservatori, abrite d'importantes peintures by Anthony Majanlahti comme St Jean Baptiste de Caravaggio et des oeuvres de titian, veronese, Rubens et Tintoretto. Une sculpture d'un énorme pied se trouve dans la cours, et faisait autrefois partie d'une statue de l'empereur Constantin. Une des ouvres fameuses est sans aucun doute la louve, une sculpture étrusque du 5ème siècle avant J-C à laquelle Romulus et Rémus furent ajoutés à la Renaissance. +39 06 0608 www.museicapitolini.org/s info.museicapitolini@comu Piazza Campidoglio, Rome ede/piazza_e_palazzi/pala ne.roma.it zzo_dei_conservatori#c Museo Barracco di Scultura Antica "Sculpturally Speaking" The Palazzo della Piccola Farnesina, built in 1523, houses the Museo Barracco di Scultura Antica, formed from a collection of pre-Roman art sculptures, Assyrian bas-reliefs, Attic vases, Egyptian hieroglyphics and exceptional Etruscan and Roman pieces. -

Museums & Attractions

MUSEUMS & ATTRACTIONS Hidden Neighborhood DERNA O Discover an area of Rome that no longer exists. Tiffany Parks fills you in. RTE M RTE A t may be called the Eternal City, but in reality, since its inception well boulevard that leads from Castel Sant’Angelo to St. Peter’s Basilica. over 2000 years ago, Rome has been in constant flux. Every building On this site, until well into the 20th century, stood a narrow ridge or Iwas built upon the foundations of an older one; every street has “spine” of medieval homes and shops, a continuation of the Borgo. In changed its course at least once. Like the tip of an iceberg, for all the the 1930s, Mussolini decided to raze this area to make way for the wide ancient ruins and medieval houses that you can see, there are myriad thoroughfare we have today. Rome gained a glorious approach to the more hidden from view, either buried underground or incorporated basilica, facilitating the access for the millions of tourists and pilgrims ELISCHI 1950 GALLERIA D’ ELISCHI 1950 into more recent buildings. In many cases, historic sites have been that visit it each year, but at the same time, hundreds of residents were B purposely destroyed, all in the name of modern city planning. displaced and a historic slice of the city disappeared. Such is the case for the so-called Spina del Borgo, literally the On occasion of this year’s jubilee, the Capitoline Museums “backbone” of the Borgo. A neighborhood of densely packed medieval is hosting an exhibit that explores this missing piece of the urban buildings clustered around St. -

Trastevere (Map P. 702, A3–B4) Is the Area Across the Tiber

400 TRASTEVERE 401 TRASTEVERE rastevere (map p. 702, A3–B4) is the area across the Tiber (trans Tiberim), lying below the Janiculum hill. Since ancient times there have been numerous artisans’ Thouses and workshops here and the inhabitants of this essentially popular district were known for their proud and independent character. It is still a distinctive district and remains in some ways a local neighbourhood, where the inhabitants greet each other in the streets, chat in the cafés or simply pass the time of day in the grocery shops. It has always been known for its restaurants but today the menus are often provided in English before Italian. Cars are banned from some of the streets by the simple (but unobtrusive) method of laying large travertine blocks at their entrances, so it is a pleasant place to stroll. Some highlights of Trastevere ª The beautiful and ancient basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere with a wonderful 12th-century interior and mosaics in the apse; ª Palazzo Corsini, part of the Gallerie Nazionali, with a collection of mainly 17th- and 18th-century paintings; ª The Orto Botanico (botanic gardens); ª The Renaissance Villa Farnesina, still surrounded by a garden on the Tiber, built in the early 16th century as the residence of Agostino Chigi, famous for its delightful frescoed decoration by Raphael and his school, and other works by Sienese artists, all commissioned by Chigi himself; HISTORY OF TRASTEVERE ª The peaceful church of San Crisogono, with a venerable interior and This was the ‘Etruscan side’ of the river, and only after the destruction of Veii by remains of the original early church beneath it; Rome in 396 bc (see p. -

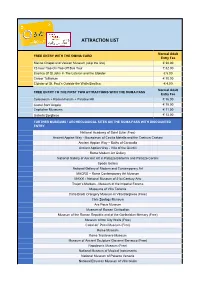

Attraction List

ATTRACTION LIST Normal Adult FREE ENTRY WITH THE OMNIA CARD Entry Fee Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museum (skip the line) € 30.00 72-hour Hop-On Hop-Off Bus Tour € 32.00 Basilica Of St.John In The Lateran and the Cloister € 5.00 Carcer Tullianum € 10.00 Cloister of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls Basilica € 4.00 Normal Adult FREE ENTRY TO THE FIRST TWO ATTRACTIONS WITH THE ROMA PASS Entry Fee Colosseum + Roman Forum + Palatine Hill € 16.00 Castel Sant’Angelo € 15.00 Capitoline Museums € 11.50 Galleria Borghese € 13.00 FURTHER MUSEUMS / ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE ROMA PASS WITH DISCOUNTED ENTRY National Academy of Saint Luke (Free) Ancient Appian Way - Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella and the Castrum Caetani Ancient Appian Way – Baths of Caracalla Ancient Appian Way - Villa of the Quintili Rome Modern Art Gallery National Gallery of Ancient Art in Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Corsini Spada Gallery National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art MACRO – Rome Contemporary Art Museum MAXXI - National Museum of 21st Century Arts Trajan’s Markets - Museum of the Imperial Forums Museums of Villa Torlonia Carlo Bilotti Orangery Museum in Villa Borghese (Free) Civic Zoology Museum Ara Pacis Museum Museum of Roman Civilization Museum of the Roman Republic and of the Garibaldian Memory (Free) Museum of the City Walls (Free) Casal de’ Pazzi Museum (Free) Rome Museum Rome Trastevere Museum Museum of Ancient Sculpture Giovanni Barracco (Free) Napoleonic Museum (Free) National Museum of Musical Instruments National Museum of Palazzo Venezia National Etruscan -

Tour Highlights.ICAA Secret Rome.6.9

Secret Rome & the Countryside: Exemplary Private Palaces, Villas & Gardens and Archeological Sites Sponsored by The Institute of Classical Architecture & Art Organized by Pamela Huntington Darling Saturday, October 3rd to Sunday, October 11th, 2015 – 8 days/8 nights Called the Eternal City, Rome is a treasure of architecture and art, history and culture, and has been an essential destination for sophisticated travelers for centuries. Yet behind the city's great monuments and museums lies a Rome unknown to even the most seasoned visitors. Our exceptional program offers an intimate group of discerning travelers unprecedented access to Rome's most exclusive and evocative treasures—a secret Rome of exquisite palazzi, villas and gardens, world-class art collections and momentous and behind-the-scenes sites accessible only to the privileged few. By exclusive personal invitation of Italian nobility, ambassadors, curators and eminent members of the Roman elite, for eight unprecedented days we will discover, with their owners, exemplary private palazzi, castles and villas—rarely, if ever, opened to the public—in the city and surrounding countryside, as well as legendary archeological sites open only by special request. During our privileged, exclusive discovery, we will observe the development of Roman architecture, décor, art and landscape design with expert lecturers, architect Thomas Rankin, historian Anthony Majanlahti and art historians Sara Magister and Frank Dabell. Program Day 1: Saturday, October 3rd Afternoon welcome and visit to the Capitoline Museums, with Professor Thomas Greene Rankin. Professor Rankin and Pamela Hunting Darling will welcome you with a brief introduction to our exceptional program, followed by a walk with Professor Rankin to the Capitoline, the most important of the Seven Hills of Rome, where we will visit the Capitoline Museums to view masterpieces of classical sculpture to set the context of the “Grand Tour.” Late afternoon private reception at the Cavalieri di Rodi, headquarters of the Knights of Malta.