COMPLAINT of KILUSANG MAYO UNO LABOR CENTER (“KMU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If Not Us, Who?

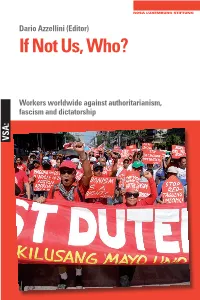

Dario Azzellini (Editor) If Not Us, Who? Workers worldwide against authoritarianism, fascism and dictatorship VSA: Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships The Editor Dario Azzellini is Professor of Development Studies at the Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas in Mexico, and visiting scholar at Cornell University in the USA. He has conducted research into social transformation processes for more than 25 years. His primary research interests are industrial sociol- ogy and the sociology of labour, local and workers’ self-management, and so- cial movements and protest, with a focus on South America and Europe. He has published more than 20 books, 11 films, and a multitude of academic ar- ticles, many of which have been translated into a variety of languages. Among them are Vom Protest zum sozialen Prozess: Betriebsbesetzungen und Arbei ten in Selbstverwaltung (VSA 2018) and The Class Strikes Back: SelfOrganised Workers’ Struggles in the TwentyFirst Century (Haymarket 2019). Further in- formation can be found at www.azzellini.net. Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships A publication by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de www.rosalux.de This publication was financially supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung with funds from the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) of the Federal Republic of Germany. The publishers are solely respon- sible for the content of this publication; the opinions presented here do not reflect the position of the funders. Translations into English: Adrian Wilding (chapter 2) Translations by Gegensatz Translation Collective: Markus Fiebig (chapter 30), Louise Pain (chapter 1/4/21/28/29, CVs, cover text) Translation copy editing: Marty Hiatt English copy editing: Marty Hiatt Proofreading and editing: Dario Azzellini This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–Non- Commercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License. -

Volume II, Number 16. 15 August 2020

UPDATES PHILIPPINES Released by the National Democratic Front of the Philippines Amsterdamsestraatweg 50, 3513AG Utrecht, The Netherlands T: : +31 30 2310431 | E: [email protected] | W: updates.ndfp.org vol iI no 16 15 AUGUST 2020 EDITORIAL Respect the dead, friend or foe It is a tradition in most cultures in the world to respect the dead, whether the deceased was a friend, a foe or an unknown. This culture of respect is even more ingrained among the Filipino people who honor, nay, even venerate, their departed. More so, many even extend the period of mourning up to forty days after the demise of their loved one. Thus, it was a shock to the people that Ka Randall Echanis, a respected champion for genuine land reform and a major consultant of the NDFP peace panel for social and economic reforms, was brutally murdered before dawn of August 10 by suspected state agents. Adding anger to the shock, on the evening of the same day, Ka Randy’s mutilated body was forcibly taken by the police from his widow, family and friends. The obvious aim for the abduction was to obliterate marks of torture from his body. This is in fact not the first time that armed minions of the regime maltreated the remains of their victims. After an armed encounter in Laguna province last 5 August, the police took the remains of three NPA members from a funeral home to their base, Camp Vicente Lim, without the knowledge much less the permission of the victims’ relatives. The three NPA victims and two more are still held in the base as of this writing. -

Since Aquino: the Philippine Tangle and the United States

OccAsioNAl PApERs/ REpRiNTS SERiEs iN CoNTEMpoRARY AsiAN STudiEs NUMBER 6 - 1986 (77) SINCE AQUINO: THE PHILIPPINE • TANGLE AND THE UNITED STATES ••' Justus M. van der Kroef SclloolofLAw UNivERsiTy of o• MARylANd. c:. ' 0 Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Jaw-ling Joanne Chang Acting Managing Editor: Shaiw-chei Chuang Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, International Legal Studies Korea University, Republic of Korea Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International Law Society All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion con tained therein. Subscription is US $15.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $20.00 for overseas. Check should be addressed to OPRSCAS and sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu. -

LEARNING from the KMU of the PHILIPPINES ---Kim Scipes, Ph.D

BUILDING GLOBAL LABOR SOLIDARITY TODAY: LEARNING FROM THE KMU OF THE PHILIPPINES ---Kim Scipes, Ph.D. Purdue University North Central, Westville, Indiana, USA New labor movements are currently emerging across the Global South. This is happening in countries as disparate as China, Egypt, and Iran. New developments are taking place within labor movements in places such as Colombia, Indonesia, Iraq, Mexico, Pakistan and Venezuela. Activists and leaders in these labor movements are seeking information from workers and unions around the world. It is exciting to see global labor solidarity develop.1 While personnel and/or resources might be in short supply for these new labor movements, one thing that should be available is information—not prescriptions saying “you must do this, you must do that,” but rather here are some of our experiences and our thoughts on them; feel free to consider and use anything that might be helpful today. However, many labor activists today know little or nothing about the last period of intense efforts to build international labor solidarity, the years 1978-2007. During these years, we saw the development of a totally new type of trade unionism—social movement unionism2—as developed by labor movements in Brazil, the Philippines and South Africa, respectively. We also saw powerful labor movements develop in Poland and South Korea. All five of these labor movements played central, if not the central role, in helping to overthrow the military dictatorship in their country: they were some of the leading proponents of popular democracy in the world! One of these labor movements from which the concept of “social movement unionism” was developed was the KMU Labor Center of the Philippines.3 It is this author’s contention that there is a lot unknown about the KMU that would help advance global labor solidarity today. -

Report Ka Fort Phillipinen07

Center for Trade Union and Human Rights Rm. 702 Culmat Building 127 E. Rodriguez Sr. Avenue, Brgy. Mariana, Quezon City telefax: 7210241 email address: [email protected] , [email protected] Fact-finding Mission Report on the Killing of Diosdado “Ka Fort” Fortuna Cabuyao and Calamba City, Laguna September 23, 2005 I. Objectives To investigate the circumstances surrounding the killing of Diosdado “Ka Fort” Fortuna as well as to gather information on the identity of the perpetrators II. Place and Date: Cabuyao and Calamba City, Laguna September 23, 2005 III. Methodology The team visited several key places relevant to Ka Fort’s death, such as the site of the murder in front of Sagara Plastics Manufacturing Co. in Brgy. Paciano Rizal, Calamba City, as well as the places he visited prior to the murder. The team conducted interviews on the witnesses, as well as the people whom Ka Fort encountered and talked to on September 22, 2005. IV. Participants The fact-finding mission was led by the Center for Trade Union and Human Rights (CTUHR) and was participated by the National Coalition for the Protection of Workers’ Rights (NCPWR), KARAPATAN National and Southern Tagalog, PAMANTIK, Pro-Labor Legal Assistance Center (PLACE), United Filipro Employees (Nestle workers’ union), Institute for Occupational Health and Safety Development, COURAGE, Gabriela-ST, Workers’ Assistance Center, Bulatlat.com, and Southern Tagalog Exposure. V. Sources of Data Witnesses from the OLALIA office, residents close to Nestle picketline and the murder site, security guards of Sagara Factory, the wife of Ka Fort and staff of PAMANTIK VI. Summary On September 22, around 5:20pm, Diosdado “Ka Fort or Ka Ding” Fortuna, 51, president of United Filipro Employees (Nestle Workers Union) and chairman of Kilusang Mayo Uno- Southern Tagalog, was shot twice while riding his motorbike by unidentified men also on board a motorbike in front of Sagara Factory in Barangay Paciano Rizal in Calamba City, Laguna while on his way home. -

Violations of ESCR in the Philippines 2008-2011

Violations of ESCR in the Philippines 2008-2011 This submission is made by the Bagong Alyansang Makabayan (New Patriotic Alliance, BAYAN) a multi- sectoral alliance composed of Kilusang Mayo Uno (May First Movement), Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (Peasant Movement of the Philippines), Anakbayan (Youth), League of Filipino Students, Kadamay (urban poor), Courage (government employees), Health Alliance for Democracy and Alliance of Concerned Teachers and other mass formations. BAYAN held a National Council meeting in February 2011 and a National Executive Committee meeting in June 2011 to gather data and consult its member organizations. It has previously made submissions for the UPR in 2007 together with IBON Foundation and has participated/observed the CESCR session on the Philippines in 2008. The period covered by the upcoming review consists of the tail-end of the Arroyo regime (2008-June 2010) and the start of the Aquino regime (July2010-Nov2011). This submission focuses on the Philippine Government’s compliance with the Convention on Economic Social and Cultural Rights after the previous UPR, as well pledges made by the Philippine Government in its candidature to the HRC1. These include: 1. Continuing to enhance domestic implementation of all human rights treaty obligations and programs, especially with regard to the eradication of poverty and fulfillment of the UN MDG 2. Continuing to be sensitive to current and emerging challenges which have an impact on human rights, such as climate change and globalization”. It bears stressing that many of the economic policies of past Arroyo regime covered in the previous UPR were merely continued by the Aquino government. -

Union Revitalization and Social Movement Unionism in the Philippines

Union Revitalization and Social Movement Unionism in the Philippines A Handbook Marie E. Aganon Melisa R. Serrano Ramon A. Certeza i Published in the Philippines by Friedrich Ebert Stiftung and U.P. School of Labor and Industrial Relations © 2009 Marie E. Aganon, Melisa R. Serrano and Ramon A. Certeza All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the authors. ISBN ____________________ Printed in the Philippines by Central Books Malaya EM G. Fernandez B.F.A Artwork Edagr Talusan Fernandez Artist Book layout Vera Eileen V. Pupos ii List of Tables Table 1 Union Membership and CBA/CNA Coverage in the 5 Philippines Table 2 Theories of Trade Union Purpose 23 Table 3 Nature of Alliances by Group 54 Box 1 Effects of Union Avoidance Tactics 10 Box 2 CLASS’s Length of Time for Organizing Due to Union 11 Avoidance by Employers List of Figures Figure 1 Map Showing Location of Hamburg 51 Figure 2 Types and Nature of Alliances Used by Philippine 63 Unions Figure 3 Alliances that Contribute to Union Aims 65 Figure 4 Success Factors of Alliances 66 Figure 5 Effectiveness of Philippine Unions 67 Figure 6 Effectiveness of Own Union 67 Figure 7 Proposed Alternatives by Number of Responses 71 Figure 8 On Whether SMU can Energize the Philippine Labor 72 Movement Figure 9 On Whether SMU can be Conducted Beyond the 73 Workplace iii CONTENTS Acknowledgment v Foreword vi Tables x Figures xiii Part 1 Unionism on the Defensive 1 What are the factors contributing to union -

Collective Memoirs of the Union of Democratic Filipinos (KDP), Edited by Rene Ciria Cruz, Cindy Domingo, and Bruce Occena

Book Review A Time to Rise: Collective Memoirs of the Union of Democratic Filipinos (KDP), edited by Rene Ciria Cruz, Cindy Domingo, and Bruce Occena. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2017. Pp. 330. ISBN 9780295742021. Sharon M. Quinsaat During its founding on 24 April 1973, the National Democratic Front (NDF) of the Philippines released a call for international support for the Philippine revolution: “To the American people, we issue a special appeal: Resolutely oppose the leaders of US imperialism for supporting and abetting the Marcos fascist regime. Stop them from converting our country into another Vietnam” (Kalayaan International, 24 April 1973). Simultaneously, the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the NDF sent messages to Filipino nationals in the US who were former members of Kabataang Makabayan, Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan, and the underground communist movement in the Philippines on the need for a united front organization in the US to support the revolutionary struggle.1 Through the leadership of Cynthia Maglaya, Bruce Occena, and Melinda Paras, about 70 young radical Filipino and Filipino-American activists formed the Katipunan ng Demokratikong Pilipino (KDP; Union of Democratic Filipinos) in Santa Cruz, California on 27 July 1973. KDP was the only anti-martial law organization that fought transnationally on two fronts: against the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines and against capitalism in the US. The connection between authoritarian rule in the Philippines and monopoly-capitalism in the US was a recurring trope that KDP deployed, not only to capture the ideological underpinnings that guided the organization, but also to reflect the lived experiences of its members. -

Chicago Sun-Times

Assassinated Filipino labor leader remembered by Zoltan Grossman Chicago Sun Times editorial, November 18, 1986 The radio news report came as a shock to me last Thursday morning. The leader of the Philippine leftist political party, Rolando Olalia, had been found dead. His hands had been tied behind his back, and his body mutilated. Followers of Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile were suspected in the assassination. I knew Rolando Olalia. The last time I saw him was in May of last year, when I was on a three- month visit to the Philippines. He hosted a feast of roast pig, pineapple and San Miguel beer for foreign unionists and journalists in Manila. They had been attending the conference of his trade union confederation Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU), or May First Movement -- founded by his father six years ago. I remember Lando as an especially warm yet shy person. His image was inconsistent with that of a fiery labor leader. Almost awkward in front of crowds, he nevertheless was respected as an heir to the Philippine tradition of uncompromising labor activism. The movement was based in the grassroots, not in any leader's personality. Nevertheless, Olalia's death may galvanize Filipino workers in the same way that the death of Benigno Aquino stirred the middle class three years ago. Lando was a mainstream lawyer until his father, Bert Olalia, urged him to take up the workers' cause. When his father died in 1984, Lando succeeded him as the head of KMU. The rank-and- file coalition grew rapidly to challenge the dictatorship of President Ferdinand Marcos, as well as Filipino and foreign industrialists. -

Philippines Unionism― Worker Voice

太田仁志編『新興国の新しい労働運動』調査研究報告書 アジア経済研究所 2019年 第4 章 Philippines Unionism ― Worker Voice, Representation and Pluralism in Industrial Relations ― Maragtas S.V. AMANTE Abstract After 117 years, Philippine unionism remain as a vehicle for worker voice and representation in industrial relations, guaranteed by the Constitution and labor laws. The first Philippine union was established in 1902. Interviews and analysis of availa- ble documents and statements of Philippine trade union leaders, labor political party groups and worker associations indicate various degrees of engagement in social and political unionism beyond economic unionism through collective bargaining. Yet, the number and membership of Philippine trade unions remained small and, therefore, weak in terms of collective bargaining. The fragmentation of unions is extreme, and competition among unions continues to make the labor movement weak. The fact that bargaining representation is subject to elections every five years leads to a lot of union raiding across and within industries, and thus unions spend their energies vying for existing membership rather than organizing new members. Without the ability to expand collective bargaining beyond these small numbers, un- ions would have no significant strength as a voice on the concerns of labor in the economic development process. The inability of unions to resolve jurisdictional problems and come together to cooperate also implies limited ability to focus on the development of solid solidarity work or collaboration. The diversity and history of Philippine trade unions also shows the need for policy reforms to move forward beyond narrow tripartism, towards greater pluralism 63 to balance competing interests. The promotion decent work and industrial democ- racy shall build on the historical experience and adjust to the emerging platforms ena- bled by technology, with changing job designs, employment relations for effective voice and representation of workers’ interest. -

Introduction

Philippine Civil Society and the Globalization Discourse INTRODUCTION The globalization process has vastly reorganized the economic, political and socio-cultural structures of many societies and countries of the world today.1 States have re-aligned their priorities and foreign policies in the name of global competitiveness and economic integration. World economic institutions have been formed to referee the rapidly collapsing trade barriers and facilitate a new world economic order brought about by globalization. Academics in various disciplines have tried to grapple with the notion of globalization by exploring and analyzing its interrelated dimension and implications. Civil society players are redefining their own missions and strategies to be able to expose, counteract, or work with the impact of a globalizing world order on various aspects of social life. The discourse on the globalization phenomenon, has certainly been rich but contentious. The debate over the nature and trajectory of globalization has been raging in local, regional, and international arenas over the past years. There is recognition of the need for further studies, more dialogues, and various venues that would enable policy-makers, civil society players and the academic community to gain fresh perspectives in analyzing the reality in which current tasks are framed. Before events within the globalizing environment completely overrun the relevance of this inquiry, the need to systematize new concepts and ideas into a more coherent pattern is seen as an important aspect of this over-all effort. This study compares and contrasts perspectives of selected organized civil society groups in the Philippines vis- a- vis the globalization discourse. Civil society groups in the Philippines define and address the impact of globalization on different fronts. -

Request for Review of the Gsp Status of the Republic of the Philippines for Violations of Worker Rights

REQUEST FOR REVIEW OF THE GSP STATUS OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FOR VIOLATIONS OF WORKER RIGHTS Submitted on June 22, 2007 to: The Office of the United States Trade Representative 600 17th Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20058 Submitted by the: International Labor Rights Fund 2001 S St., NW #420 Washington, DC 20009 Contact: Brian Campbell Phone: (202) 347-4100 ext. 102 Fax: (202) 347-4885 Email: [email protected] International Labor Rights Fund Request for Review of the Republic of the Philippines’ country eligibility under the Generalized System of Preferences Program (Country Practice Petition) Submission to the Office of the US Trade Representative in response to Federal Register Notice Regarding the Initiation of the 2007 Annual GSP Product and Country Eligibility Practices Review and Change in Deadlines for Filing Certain Petitions (FR Doc. E7-9756 Filed 5-18-07) Re: Philippines For further information contact Brian Campbell, Attorney, International Labor Rights Fund ([email protected], 202 347 4100 x 102) International Labor Rights Fund Suite 420 2001 S Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 Tel (202)347-4100 Fax (202)347-4885 I. Introduction The International Labor Rights Fund (ILRF) presents this petition pursuant to 15 C.F.R. §2007(b) to request a review of the Republic of the Philippines’ designation as a beneficiary country under the Trade Act of 1974, Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), 19 U.S.C. §2461 et seq., as amended. The Government of the Republic of the Philippines (or GRP) has failed to takes steps to afford its workers “internationally recognized worker rights" as required under 19 U.S.C.