Query Optimization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Query Optimization Techniques - Tips for Writing Efficient and Faster SQL Queries

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 4, ISSUE 10, OCTOBER 2015 ISSN 2277-8616 Query Optimization Techniques - Tips For Writing Efficient And Faster SQL Queries Jean HABIMANA Abstract: SQL statements can be used to retrieve data from any database. If you've worked with databases for any amount of time retrieving information, it's practically given that you've run into slow running queries. Sometimes the reason for the slow response time is due to the load on the system, and other times it is because the query is not written to perform as efficiently as possible which is the much more common reason. For better performance we need to use best, faster and efficient queries. This paper covers how these SQL queries can be optimized for better performance. Query optimization subject is very wide but we will try to cover the most important points. In this paper I am not focusing on, in- depth analysis of database but simple query tuning tips & tricks which can be applied to gain immediate performance gain. ———————————————————— I. INTRODUCTION Query optimization is an important skill for SQL developers and database administrators (DBAs). In order to improve the performance of SQL queries, developers and DBAs need to understand the query optimizer and the techniques it uses to select an access path and prepare a query execution plan. Query tuning involves knowledge of techniques such as cost-based and heuristic-based optimizers, plus the tools an SQL platform provides for explaining a query execution plan.The best way to tune performance is to try to write your queries in a number of different ways and compare their reads and execution plans. -

SAQE: Practical Privacy-Preserving Approximate Query Processing for Data Federations

SAQE: Practical Privacy-Preserving Approximate Query Processing for Data Federations Johes Bater Yongjoo Park Xi He Northwestern University University of Illinois (UIUC) University of Waterloo [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Xiao Wang Jennie Rogers Northwestern University Northwestern University [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION A private data federation enables clients to query the union of data Querying the union of multiple private data stores is challeng- from multiple data providers without revealing any extra private ing due to the need to compute over the combined datasets without information to the client or any other data providers. Unfortu- data providers disclosing their secret query inputs to anyone. Here, nately, this strong end-to-end privacy guarantee requires crypto- a client issues a query against the union of these private records graphic protocols that incur a significant performance overhead as and he or she receives the output of their query over this shared high as 1,000× compared to executing the same query in the clear. data. Presently, systems of this kind use a trusted third party to se- As a result, private data federations are impractical for common curely query the union of multiple private datastores. For example, database workloads. This gap reveals the following key challenge some large hospitals in the Chicago area offer services for a cer- in a private data federation: offering significantly fast and accurate tain percentage of the residents; if we can query the union of these query answers without compromising strong end-to-end privacy. databases, it may serve as invaluable resources for accurate diag- To address this challenge, we propose SAQE, the Secure Ap- nosis, informed immunization, timely epidemic control, and so on. -

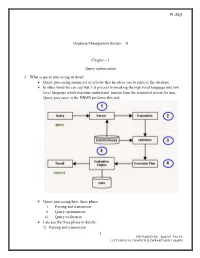

PL/SQL 1 Database Management System

PL/SQL Database Management System – II Chapter – 1 Query optimization 1. What is query processing in detail: Query processing means set of activity that involves you to retrieve the database In other word we can say that it is process to breaking the high level language into low level language which machine understand and perform the requested action for user. Query processor in the DBMS performs this task. Query processing have three phase i. Parsing and transaction ii. Query optimization iii. Query evaluation Lets see the three phase in details : 1) Parsing and transaction : 1 PREPARED BY: RAHUL PATEL LECTURER IN COMPUTER DEPARTMENT (BSPP) PL/SQL . Check syntax and verify relations. Translate the query into an equivalent . relational algebra expression. 2) Query optimization : . Generate an optimal evaluation plan (with lowest cost) for the query plan. 3) Query evaluation : . The query-execution engine takes an (optimal) evaluation plan, executes that plan, and returns the answers to the query Let us discuss the whole process with an example. Let us consider the following two relations as the example tables for our discussion; Employee(Eno, Ename, Phone) Proj_Assigned(Eno, Proj_No, Role, DOP) where, Eno is Employee number, Ename is Employee name, Proj_No is Project Number in which an employee is assigned, Role is the role of an employee in a project, DOP is duration of the project in months. With this information, let us write a query to find the list of all employees who are working in a project which is more than 10 months old. SELECT Ename FROM Employee, Proj_Assigned WHERE Employee.Eno = Proj_Assigned.Eno AND DOP > 10; Input: . -

An Overview of Query Optimization

An Overview of Query Optimization Why? Improving query processing time. Fast response is important in several db applications. Is it possible? Yes, but relative. A query can be evaluated in several ways. We can list all of them and then find the best among them. Sometime, we might not be able to do it because of the number of possible ways to evaluate the query is huge. We need to settle for a compromise: we try to find one that is reasonably good. Typical Query Evaluation Steps in DBMS. The DBMS has the following components for query evaluation: SQL parser, quey optimizer, cost estimator, query plan interpreter. The SQL parser accepts a SQL query and generates a relational algebra expression (sometime, the system catalog is considered in the generation of the expression). This expression is fed into the query optimizer, which works in conjunction with the cost estimator to generate a query execution plan (with hopefully a reasonably cost). This plan is then sent to the plan interpreter for execution. How? The query optimizer uses several heuristics to convert a relational algebra expression to an equivalent expres- sion which (hopefully!) can be computed efficiently. Different heuristics are (see explaination in textbook): (i) transformation between selection and projection; 1. Cascading of selection: σC1∧C2 (R) ≡ σC1 (σC2 (R)) 2. Commutativity of selection: σC1 (σC2 (R)) ≡ σC2 (σC1 (R)) 0 3. Cascading of projection: πAtts(R) = πAtts(πAtts0 (R)) if Atts ⊆ Atts 4. Commutativity of projection: πAtts(σC (R)) = σC (πAtts((R)) if Atts includes all attributes used in C. (ii) transformation between Cartesian product and join; 1. -

Veritas: Shared Verifiable Databases and Tables in the Cloud

Veritas: Shared Verifiable Databases and Tables in the Cloud Lindsey Alleny, Panagiotis Antonopoulosy, Arvind Arasuy, Johannes Gehrkey, Joachim Hammery, James Huntery, Raghav Kaushiky, Donald Kossmanny, Jonathan Leey, Ravi Ramamurthyy, Srinath Settyy, Jakub Szymaszeky, Alexander van Renenz, Ramarathnam Venkatesany yMicrosoft Corporation zTechnische Universität München ABSTRACT A recent class of new technology under the umbrella term In this paper we introduce shared, verifiable database tables, a new "blockchain" [11, 13, 22, 28, 33] promises to solve this conundrum. abstraction for trusted data sharing in the cloud. For example, companies A and B could write the state of these shared tables into a blockchain infrastructure (such as Ethereum [33]). The KEYWORDS blockchain then gives them transaction properties, such as atomic- ity of updates, durability, and isolation, and the blockchain allows Blockchain, data management a third party to go through its history and verify the transactions. Both companies A and B would have to write their updates into 1 INTRODUCTION the blockchain, wait until they are committed, and also read any Our economy depends on interactions – buyers and sellers, suppli- state changes from the blockchain as a means of sharing data across ers and manufacturers, professors and students, etc. Consider the A and B. To implement permissioning, A and B can use a permis- scenario where there are two companies A and B, where B supplies sioned blockchain variant that allows transactions only from a set widgets to A. A and B are exchanging data about the latest price for of well-defined participants; e.g., Ethereum [33]. widgets and dates of when widgets were shipped. -

Introduction to Query Processing and Optimization

Introduction to Query Processing and Optimization Michael L. Rupley, Jr. Indiana University at South Bend [email protected] owned_by 10 No ABSTRACT All database systems must be able to respond to The drivers relation: requests for information from the user—i.e. process Attribute Length Key? queries. Obtaining the desired information from a driver_id 10 Yes database system in a predictable and reliable fashion is first_name 20 No the scientific art of Query Processing. Getting these last_name 20 No results back in a timely manner deals with the age 2 No technique of Query Optimization. This paper will introduce the reader to the basic concepts of query processing and query optimization in the relational The car_driver relation: database domain. How a database processes a query as Attribute Length Key? well as some of the algorithms and rule-sets utilized to cd_car_name 15 Yes* produce more efficient queries will also be presented. cd_driver_id 10 Yes* In the last section, I will discuss the implementation plan to extend the capabilities of my Mini-Database Engine program to include some of the query 2. WHAT IS A QUERY? optimization techniques and algorithms covered in this A database query is the vehicle for instructing a DBMS paper. to update or retrieve specific data to/from the physically stored medium. The actual updating and 1. INTRODUCTION retrieval of data is performed through various “low-level” operations. Examples of such operations Query processing and optimization is a fundamental, if for a relational DBMS can be relational algebra not critical, part of any DBMS. To be utilized operations such as project, join, select, Cartesian effectively, the results of queries must be available in product, etc. -

SQL Database Management Portal

APPENDIX A SQL Database Management Portal This appendix introduces you to the online SQL Database Management Portal built by Microsoft. It is a web-based application that allows you to design, manage, and monitor your SQL Database instances. Although the current version of the portal does not support all the functions of SQL Server Management Studio, the portal offers some interesting capabilities unique to SQL Database. Launching the Management Portal You can launch the SQL Database Management Portal (SDMP) from the Windows Azure Management Portal. Open a browser and navigate to https://manage.windowsazure.com, and then login with your Live ID. Once logged in, click SQL Databases on the left and click on your database from the list of available databases. This brings up the database dashboard, as seen in Figure A-1. To launch the management portal, click the Manage icon at the bottom. Figure A-1. SQL Database dashboard in Windows Azure Management Portal 257 APPENDIX A N SQL DATABASE MANAGEMENT PORTAL N Note You can also access the SDMP directly from a browser by typing https://sqldatabasename.database. windows.net, where sqldatabasename is the server name of your SQL Database. A new web page opens up that prompts you to log in to your SQL Database server. If you clicked through the Windows Azure Management Portal, the database name will be automatically filled and read-only. If you typed the URL directly in a browser, you will need to enter the database name manually. Enter a user name and password; then click Log on (Figure A-2). -

Query Optimization for Dynamic Imputation

Query Optimization for Dynamic Imputation José Cambronero⇤ John K. Feser⇤ Micah J. Smith⇤ Samuel Madden MIT CSAIL MIT CSAIL MIT LIDS MIT CSAIL [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT smaller than the entire database. While traditional imputation Missing values are common in data analysis and present a methods work over the entire data set and replace all missing usability challenge. Users are forced to pick between removing values, running a sophisticated imputation algorithm over a tuples with missing values or creating a cleaned version of their large data set can be very expensive: our experiments show data by applying a relatively expensive imputation strategy. that even a relatively simple decision tree algorithm takes just Our system, ImputeDB, incorporates imputation into a cost- under 6 hours to train and run on a 600K row database. based query optimizer, performing necessary imputations on- Asimplerapproachmightdropallrowswithanymissing the-fly for each query. This allows users to immediately explore values, which can not only introduce bias into the results, but their data, while the system picks the optimal placement of also result in discarding much of the data. In contrast to exist- imputation operations. We evaluate this approach on three ing systems [2, 4], ImputeDB avoids imputing over the entire real-world survey-based datasets. Our experiments show that data set. Specifically,ImputeDB carefully plans the placement our query plans execute between 10 and 140 times faster than of imputation or row-drop operations inside the query plan, first imputing the base tables. Furthermore, we show that resulting in a significant speedup in query execution while the query results from on-the-fly imputation differ from the reducing the number of dropped rows. -

Plan Stitch: Harnessing the Best of Many Plans

Plan Stitch: Harnessing the Best of Many Plans Bailu Ding Sudipto Das Wentao Wu Surajit Chaudhuri Vivek Narasayya Microsoft Research Redmond, WA 98052, USA fbadin, sudiptod, wentwu, surajitc, [email protected] ABSTRACT optimizer chooses multiple query plans for the same query, espe- Query performance regression due to the query optimizer select- cially for stored procedures and query templates. ing a bad query execution plan is a major pain point in produc- The query optimizer often makes good use of the newly-created indexes and statistics, and the resulting new query plan improves tion workloads. Commercial DBMSs today can automatically de- 1 tect and correct such query plan regressions by storing previously- in execution cost. At times, however, the latest query plan chosen executed plans and reverting to a previous plan which is still valid by the optimizer has significantly higher execution cost compared and has the least execution cost. Such reversion-based plan cor- to previously-executed plans, i.e., a plan regresses [5, 6, 31]. rection has relatively low risk of plan regression since the deci- The problem of plan regression is painful for production applica- sion is based on observed execution costs. However, this approach tions as it is hard to debug. It becomes even more challenging when ignores potentially valuable information of efficient subplans col- plans change regularly on a large scale, such as in a cloud database lected from other previously-executed plans. In this paper, we service with automatic index tuning. Given such a large-scale pro- propose a novel technique, Plan Stitch, that automatically and op- duction environment, detecting and correcting plan regressions in portunistically combines efficient subplans of previously-executed an automated manner becomes crucial. -

Exploring Query Re-Optimization in a Modern Database System

Radboud University Nijmegen Institute of Computing and Information Sciences Exploring Query Re-Optimization In a Modern Database System Master Thesis Computing Science Supervisor: Prof. dr. ir. Arjen P. Author: de Vries BSc Laurens N. Kuiper Second reader: Prof. dr. ir. Djoerd Hiemstra May 2021 Abstract The standard approach to query processing in database systems is to optimize before executing. When available statistics are accurate, optimization yields the optimal plan, and execution is as quick as it can be. However, when queries become more complex, the quality of statistics degrades, which leads to sub-optimal query plans, sometimes up to several orders of magnitude worse. Improving statistics for these queries is infeasible because the cardinality estimation error propagates exponentially through the plan. This problem can be alleviated through re-optimization, which is to progressively optimize the query, executing parts of the plan at a time, improving plan quality at the cost of additional overhead. In this work, re-optimization is implemented and simulated in DuckDB, a main-memory database system designed for analytical workloads, and evaluated on the Join Order Benchmark. Total plan cost of the benchmark is reduced by up to 44% using this method, and a reduction in end-to-end query latency of up to 20% is observed using only simple re-optimization schemes, showing the potential of this approach. Acknowledgements The past year has been a challenging and exciting year. From breaking my leg to starting a job, and finally finishing my thesis. I would like to thank everyone who supported me during this period, and helped me get here. -

Scalable Query Optimization for Efficient Data Processing Using

1 Scalable Query Optimization for Efficient Data Processing using MapReduce Yi Shan #1, Yi Chen 2 # School of Computing, Informatics, and Decision Systems Engineering, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA School of Management, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, NJ, USA 1 [email protected] 2 [email protected] 1#*#!2_ Abstract—MapReduce is widely acknowledged by both indus- $0-+ --- try and academia as an effective programming model for query 5�# 0X0,"0X0,"0X0 processing on big data. It is crucial to design an optimizer which finds the most efficient way to execute an SQL query using Fig. 1. Query Q1 MapReduce. However, existing work in parallel query processing either falls short of optimizing an SQL query using MapReduce '8#/ '8#/ or the time complexity of the optimizer it uses is exponential. Also, industry solutions such as HIVE, and YSmart do not '8#/ optimize the join sequence of an SQL query and cannot guarantee '8#/ '8#/ '8#/ an optimal execution plan. In this paper, we propose a scalable '8#/ optimizer for SQL queries using MapReduce, named SOSQL. '8#/ Experiments performed on Google Cloud Platform confirmed '8#/ the scalability and efficiency of SOSQL over existing work. '8#/ '8#/ '8#/ '8#/ '8#/ (a) QP1 (b) QP2 I. INTRODUCTION Fig. 2. Query Plans of Query Q1 It becomes increasingly important to process SQL queries further generates a query execution plan consisting of three on big data. Query processing consists of two parts: query parallel jobs, one for each binary join operation, as illustrated optimization and query execution. The query optimizer first in Figure 3(a). -

Queryguard: Privacy-Preserving Latency-Aware Query Optimization for Edge Computing

QueryGuard: Privacy-preserving Latency-aware Query Optimization for Edge Computing Runhua Xu ∗, Balaji Palanisamy y and James Joshi z School of Computing and Information University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA USA ∗[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—The emerging edge computing paradigm has en- adopting distributed database techniques in edge computing abled applications having low response time requirements to brings new challenges and concerns. First, in contrast to meet the quality of service needs of applications by moving the cloud data centers where cloud servers are managed through computations to the edge of the network that is geographically closer to the end-users and end-devices. Despite the low latency strict and regularized policies, edge nodes may not have the advantages provided by the edge computing model, there are same degree of regulatory and monitoring oversight. This significant privacy risks associated with the adoption of edge may lead to higher privacy risks compared to that in cloud computing services for applications dealing with sensitive data. servers. In particular, when dealing with a join query, tra- In contrast to cloud data centers where system infrastructures are ditional distributed query processing techniques sometimes managed through strict and regularized policies, edge computing nodes are scattered geographically and may not have the same ship selected or projected data to different nodes, some of degree of regulatory and monitoring oversight. This can lead which may be untrusted or semi-trusted. Thus, such techniques to higher privacy risks for the data processed and stored at may lead to greater disclosure of private information within the edge nodes, thus making them less trusted.