ARSC Journal, Xiil:L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal, Spring 1992 69 Sound Recording Reviews

SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First Hundred Years CS090/12 (12 CDs: monaural, stereo; ADD)1 Available only from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 220 S. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL, for $175 plus $5 shipping and handling. The Centennial Collection-Chicago Symphony Orchestra RCA-Victor Gold Seal, GD 600206 (3 CDs; monaural, stereo, ADD and DDD). (total time 3:36:3l2). A "musical trivia" question: "Which American symphony orchestra was the first to record under its own name and conductor?" You will find the answer at the beginning of the 12-CD collection, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First 100 Years, issued by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). The date was May 1, 1916, and the conductor was Frederick Stock. 3 This is part of the orchestra's celebration of the hundredth anniversary of its founding by Theodore Thomas in 1891. Thomas is represented here, not as a conductor (he died in 1904) but as the arranger of Wagner's Triiume. But all of the other conductors and music directors are represented, as well as many guests. With one exception, the 3-CD set, The Centennial Collection: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, from RCA-Victor is drawn from the recordings that the Chicago Symphony made for that company. All were released previously, in various formats-mono and stereo, 78 rpm, 45 rpm, LPs, tapes, and CDs-as the technologies evolved. Although the present digital processing varies according to source, the sound is generally clear; the Reiner material is comparable to RCA-Victor's on-going reissues on CD of the legendary recordings produced by Richard Mohr. -

Bsolive.Com Concert Programme Autumn 2020 Bsolive.Com Concert

Concert Programme Autumn 2020 bsolive.com Welcome It’s my great pleasure to welcome you to this What amazing musical portraits Elgar week’s BSO concert of two British created in this dazzling sequence of masterworks, and a gem by Fauré. inventive musical vignettes, for instance, to name but three - the humorous Troyte, the The Britten and Elgar works hold special serious intellect of A.J Jaeger aka ‘Nimrod’, resonances for me. I’d been taken on holiday and the bulldog Dan, the beloved pet of to the Suffolk coast as a child, and when, George Sinclair, organist of Hereford aged fourteen, I first saw Peter Grimes, I was Cathedral, paddling furiously up the river totally bowled over by the power of the Wye. music, and the way it evoked, especially in the Four Sea Interludes, those East Anglican In between, I’m relishing the prospect of the landscapes and coast seascapes that I BSO’s Principal Cello, Jesper Svedberg, remembered. Later, at university in Norwich, bringing his poetic musicianship to Fauré’s I had the privilege of singing under Britten at haunting Élégie. I’m also looking forward to the Aldeburgh Festival, as well as meeting hearing the Britten and Elgar conducted by him at his home, The Red House. For me, David Hill, whose interpretations of English these memories are unforgettable. music are second to none, witnessed, not just in his performances, but also in his Elgar was another discovery of my teens; superb recordings, many, of course, with the when growing up in Birmingham, BSO. Worcestershire and Elgar country was only a couple of hours bus ride away. -

Csoa-Announces-November-2020

For Immediate Release: Press Contacts: October 22, 2020 Eileen Chambers 312-294-3092 Dana Navarro 312-294-3090 CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ASSOCIATION ANNOUNCES NOVEMBER 2020 DIGITAL PROGRAMS Highlights include Two New Episodes of CSO Sessions, Free Thanksgiving Day Digital Premiere of CSO/Solti Beethoven Fifth Symphony Archival Broadcast, Veteran’s Day Tribute Program from CSO Trumpet John Hagstrom, and More CSO Sessions Episode 7 features Former Solti Conducting Apprentice Erina Yashima Leading Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale with Actor James Earl Jones II New On-Demand Recital from Symphony Center Presents features Pianist Jorge Federico Osorio NOVEMBER 5-29 CHICAGO—The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association (CSOA) announces details for its November 2020 digital programs that provide audiences both locally and around the world a way to connect with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra online. Highlights include the premiere of two new episodes in the CSO Sessions series, two archival CSO television broadcast programs, a new piano recital from Symphony Center Presents and a Veteran’s Day digital premiere of a tribute to veterans that highlights the trumpet’s key role in military and orchestral music. Programs will be available via CSOtv, the new video portal for free and premium on-demand videos. A chronological list of November 2020 digital programs is available here. CSO Sessions The new digital series of on-demand, high-definition video recordings of chamber music and chamber orchestra concerts feature performances by Chicago Symphony Orchestra musicians filmed in Orchestra Hall at Symphony Center. Programs for the CSO Sessions series are developed with artistic guidance from Music Director Riccardo Muti. -

Tomasz Konieczny

Tomasz Konieczny BASSBARITON Altenkamp 40 Tomasz Konieczny 40885 Ratingen, Deutschland Tel.: +49 2102 5889606 Ratingen, 02.10.2014 Mobil.: +49 172 3469559 Fax: +49 321 21247271 E-Mail: [email protected] www.tomasz-konieczny.com AUSGEWÄHLTES REPERTOIR Komponist Oper Partie Sprache Wo und wann zuletzt gesungen Beethoven L. van Fidelio Pizarro Deutsch Nationaltheater Mannheim 2004/05, Burgarena Reinsberg 2008, Dirigent Martin Haselböck, NSO Washington 2012, Dirigent Christoph Eschenbach, Bayerische Staatsoper München 2012, Staatsoper Wien 2013, Dirigent Franz Welser-Möst Berlioz H. Les Troyens Narbal, Französisch Nationaltheater Mannheim 2003-2005, Oper Leipzig 2003/04 Berlioz H. Les Troyens L’Ombre d’Hecto Französisch Nationaltheater Mannheim 2003-2005 Bizet G. Carmen Escamillo Französisch Nationaltheater Mannheim 2002-04, Deutsche Oper am Rhein 2012 - 2013 Britten B. Peter Grimes Balstrode Deutsch Deutsche Oper am Rhein Düsseldorf 2009-11 Dirigent Axel Kober, Deutsche Oper am Rhein 2013, Dirigent Wen-Pin Chien Britten B. Sommernachtstraum Zettel/Bottom Deutsch Deutsche Oper am Rhein 2006/07 Debussy C. Pelleas und Melisande Golaud Französisch Deutsche Oper am Rhein 2007-09 Haendel G.F Acis und Galatea Polyphemus Englisch Burgarena Reinsberg 2010, Dirigent Martin Haselböck Hindemith P. Cardillac Goldhändler Deutsch Staatsoper Wien, Dirigent Franz Welser-Möst, 2010, 2012 Janáček L. Die Sache Makropulos Kolenatý, Dr. Tschechisch Teatro Real Madrid 2008 Massenet J. Cendrillon Pandolfe Französisch Theater Lübeck 2000/01 Mozart W.A. Don Giovanni Commendatore Italienisch Salzburger Festspiele 2014, Dirigent Christoph Eschenbach Mozart W.A. Zauberflöte Sarastro Deutsch Nationaltheater Mannheim 2003-2005, Dirigent Adam Fischer. Staatsoper Stuttgart 2005-2006, Dirigent Lothar Zagrosek Mozart W.A Hochzeit des Figaro Figaro Italienisch Oper Posen (Polen) Polnisch Nyman M. -

January 1946) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 1-1-1946 Volume 64, Number 01 (January 1946) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 64, Number 01 (January 1946)." , (1946). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/199 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7 A . " f ft.S. &. ft. P. deed not Ucende Some Recent Additions Select Your Choruses conceit cuid.iccitzt fotidt&{ to the Catalog of Oliver Ditson Co. NOW PIANO SOLOS—SHEET MUSIC The wide variety of selections listed below, and the complete AND PUBLISHERS in the THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS, AUTHORS BMI catalogue of choruses, are especially noted as compo- MYRA ADLER Grade Pr. MAUDE LAFFERTY sitions frequently used by so many nationally famous edu- payment of the performing fee. Christmas Candles .3-4 $0.40 The Ball in the Fountain 4 .40 correspondence below reaffirms its traditional stand regarding ?-3 Happy Summer Day .40 VERNON LANE cators in their Festival Events, Clinics and regular programs. BERENICE BENSON BENTLEY Mexican Poppies 3 .35 The Witching Hour .2-3 .30 CEDRIC W. -

LIVE from LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 P.M. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 p.m. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East.Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East. Celebrating the New Year with music is nothing new for Maazel: he holds the modern record for most appearances as conductor of the celebrated New Year’s Day concerts in Vienna by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. There, of course, the fare is made up mostly of music by the waltzing Johann Strauss family, father and sons. For his New Year’s Eve concert with the New York Philharmonic Maazel has chosen quintessentially American music by the composer considered by many to be America’s closest equivalent to the Strausses, George Gershwin. -

Programme Scores 180627Da

Symposium Richard Wagner and his successors in the Austro-German conducting tradition Friday/Saturday, 2/3 November 2018 Bern University of the Arts, Papiermühlestr. 13a/d A symposium of the Research Area Interpretation – Bern University of the Arts, in collaboration with the Royal Academy of Music, London www.hkb-interpretation.ch/annotated-scores Richard Wagner published the first major treatise on conducting and interpretation in 1869. His ideas on how to interpret the core Classical and early Romantic orchestral repertoire were declared the benchmark by subsequent generations of conductors, making him the originator of a conducting tradition by which those who came after him defined their art – starting with Wagner’s student Hans von Bülow and progressing from him to Arthur Nikisch, Felix Weingartner, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Wilhelm Furtwängler and beyond. This conference will bring together leading experts in the research field in question. A workshop and concert with an orchestra with students of the Bern University of the Arts, the Hochschule Luzern – Music and the Royal Academy of Music London, directed by Prof. Ray Holden from the project partner, the Royal Academy of Music, will offer a practical perspective on the interpretation history of the Classical repertoire. A symposium of the Research Area Interpretation – Bern University of the Arts, in collaboration with the Royal Academy of Music, London Head Research Area Interpretation: Martin Skamletz Responsible for the conference: Chris Walton Scientific collaborator: Daniel Allenbach Administration: Sabine Jud www.hkb.bfh.ch/interpretation www.hkb-interpretation.ch Funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation SNSF Media partner Symposium Richard Wagner and his successors Friday, 2 November 2018 HKB, Kammermusiksaal, Papiermühlestr. -

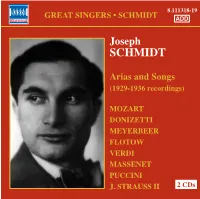

111318-19 Bk Jschmidt EU 10/15/07 2:47 PM Page 8

111318-19 bk JSchmidt EU 10/15/07 2:47 PM Page 8 8.111318-19 CD 1: CD 2: GREAT SINGERS • SCHMIDT Tracks 1, 2, 5 and 9: Tracks 1, 5 and 16: ADD Berlin State Opera Orchestra • Selmar Meyrowitz Orchestra • Felix Günther Tracks 3 and 4: Tracks 2, 6-9, 20-23: Vienna Parlophon Orchestra • Felix Günther Berlin State Opera Orchestra Selmar Meyrowitz Joseph Track 6: Berlin State Opera Orchestra • Clemens Schmalstich Tracks 3, 4, and 13: Berlin State Opera Orchestra SCHMIDT Tracks 7 and 8: Frieder Weissmann Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra • Selmar Meyrowitz Tracks 10-12, 14, 15, 18, and 19: Track 10: Orchestra • Otto Dobrindt With Max Saal, harp Arias and Songs Track 17: Track 11: Orchestra • Clemens Schmalstich Orchestra and Chorus • Clemens Schmalstich (1929-1936 recordings) Tracks 12 and 13: Languages: Berlin Symphony Orchestra • Frieder Weissmann CD 1: MOZART Tracks 14, 15, 17, 18 and 24: Tracks 1, 3-6, 9-13, 16-18, 21-24 sung in German Orchestra of the Staatsoper Berlin Tracks 2, 7, 8, 14, 15, 19, 20 sung in Italian Frieder Weissmann DONIZETTI CD 2: Track 16: Tracks 1-16 sung in German MEYERBEER Orchestra • Leo Blech Track 17 sung in Spanish Tracks 18-23 sung in Italian Tracks 19 and 20: FLOTOW Orchestra • Walter Goehr Tracks 21-23: VERDI Orchestra • Otto Dobrindt MASSENET PUCCINI J. STRAUSS II 2 CDs 8.111318-19 8 111318-19 bk JSchmidt EU 10/15/07 2:47 PM Page 2 Joseph Schmidt (1904-1942) LEHAR: Das Land des Lächelns: MAY: Ein Lied geht um die Welt: 8 Von Apfelblüten eine Kranz (Act I) 3:43 ^ Wenn du jung bist, gehört dir die Welt 3:09 Arias and Songs (1929-1936 recordings) Recorded on 24th October 1929; Recorded in January 1934; Joseph Schmidt’s short-lived career was like that of a 1924 he decided to take the plunge into a secular Mat. -

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ Masterpiece the Pinnacle of a High-Octane Year: Karabits, Montero and More

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ masterpiece the pinnacle of a high-octane year: Karabits, Montero and more 2 October 2019 – 13 May 2020 Kirill Karabits, Chief Conductor of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra [credit: Konrad Cwik] EMBARGO: 08:00 Wednesday 15 May 2019 • Kirill Karabits launches the season – his eleventh as Chief Conductor of the BSO – with a Weimar- themed programme featuring the UK premiere of Liszt’s melodrama Vor hundert Jahren • Gabriela Montero, Venezuelan pianist/composer, is the 2019/20 Artist-in-Residence • Concert staging of Richard Strauss’s opera Elektra at Symphony Hall, Birmingham and Lighthouse, Poole under the baton of Karabits, with a star-studded cast including Catherine Foster, Allison Oakes and Susan Bullock • The Orchestra celebrates the second year of Marta Gardolińska’s tenure as BSO Leverhulme Young Conductor in Association • Pianist Sunwook Kim makes his professional conducting debut in an all-Beethoven programme • The Orchestra continues its Voices from the East series with a rare performance of Chary Nurymov’s Symphony No. 2 and the release of its celebrated Terterian performance on Chandos • Welcome returns for Leonard Elschenbroich, Ning Feng, Alexander Gavrylyuk, Steven Isserlis, Simone Lamsma, John Lill, Carlos Miguel Prieto, Robert Trevino and more • Main season debuts for Jake Arditti, Stephen Barlow, Andreas Bauer Kanabas, Jeremy Denk, Tobias Feldmann, Andrei Korobeinikov and Valentina Peleggi • The Orchestra marks Beethoven’s 250th anniversary, with performances by conductors Kirill Karabits, Sunwook Kim and Reinhard Goebel • Performances at the Barbican Centre, Sage Gateshead, Cadogan Hall and Birmingham Symphony Hall in addition to the Orchestra’s regular venues across a 10,000 square mile region in the South West Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra announces its 2019/20 season with over 140 performances across the South West and beyond. -

WAGNER Die Walküre

660172-74 bk Walküre US 17/7/06 10:28 Page 16 3 CDs Recorded at the Staatsoper Stuttgart, Germany, WAGNER on 29th September 2002 and 2nd January 2003. General Director: Prof. Klaus Zehelein Die Walküre Executive Producers: Dr Reinhard Ermen (SWR Radio), Gambill • Jun • Rootering • Denoke • Behle • Vaughn Dr Dietrich Mack (SWR TV) and Paul Smaczny (EuroArts) Staatsoper Stuttgart • Staatsorchester Stuttgart Producer: Thomas Angelkorte Editor: Irmgard Bauer Lothar Zagrosek Engineers: Brigitte Hermann and Karl-Heinz Runde This performance of Die Walküre is the second part of Wagner’s Ring cycle recorded live during Stuttgart Opera’s 2002/2003 season. For the first time in the history of the Ring cycle each of the four operas was staged with separate producers and casts. A production of EuroArts Music International GmbH and Südwestrundfunk in co-operation with ARTE Gefördert von der Medien- und Filmgesellschaft Baden-Württemberg 8.660172-74 16 660172-74 bk Walküre US 17/7/06 10:28 Page 2 Die Walküre Stuttgart Staatsorchester (The Valkyrie) Established in 1589 as the Court Orchestra of Württemberg, the Württemberg Stuttgart State Orchestra has a history The First Day of over four hundred years. Over the generations there have been collaborations with musicians of distinction, among them Leonhard Lechner, the Frobergers, Niccolò Jommelli, Johann Rudolf Zumsteeg, Konradin Kreutzer, of Johann Nepomuk Hummel and Carl Maria von Weber. Berlioz praised the orchestra, when he appeared with it as Der Ring des Nibelungen conductor, and in the 1880s Stuttgart was one of the first to stage the complete Ring cycle, conducted by the then (The Ring of the Nibelung) General Music Director Herman Zumpe, who had assisted Wagner at the first Bayreuth Festival. -

Festival of Strings 2017 Flier

Festival of Strings 2017 Five Consecutive days of Concerts and Master Classes with Internationally Recognized Artists and our own SHSU faculty Dylana Jenson (violin), The Solera String Quartet with Josu de Solaun (piano), The Kolonneh String Quartet (SHSU faculty) • Thursday, October 5, Concert Hall, 2:30-5:00 pm Master class with Dylana Jenson • Friday, October 6, Recital Hall 1:00-3:00 pm Master class with Dylana Jenson • Friday, October 6, Concert Hall, 7:30 pm SHSU Symphony Orchestra Concert with guest soloist Daniel Saenz (cello) VENUE CHANGE! • Saturday, October 7, Recital Hall, 7:30 pm University Heights Baptist Church Guest Artist Recital 2400 Sycamore Ave, Huntsville, TX 77340 Dylana Jenson, (violin) with Josu de Solaun (piano) •Sunday, October 8, Recital Hall, 3:30 pm Guest Artist Recital The Solera String Quartet with Josu de Solaun (piano) • Monday, October 9, Recital Hall, 7:30 pm The Kolonneh String Quartet www.shsu.edu/music/events Sam Houston State University Festival of Strings 2017 Guest Artists DYLANA JENSON Dylana Jenson has performed with most major orchestras in the United States and traveled to Europe, Australia, Japan and Latin America for concerts, recitals and recordings. After her triumphant success at the Tchaikovsky Competi- tion, where she became the youngest and first American woman to win the Silver Medal, she made her Carnegie Hall debut playing the Sibelius Concerto with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Following her most recent Carnegie Hall performance, Jenson again electrified both audience and critics in her per- formance of Karl Goldmark's violin concerto. According to Strad Magazine, "In Jenson's hands, even lyrical passages had an intense, tremulous quality.. -

N E W S R E L E A

N E W S R E L E A S E CONTACT: Katherine Blodgett Vice President of Public Relations and Communications Phone: 215.893.1939 E-mail: [email protected] Jesson Geipel Public Relations Manager FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Phone: 215.893.3136 DATE: October 18, 2012 E-mail: [email protected] YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN’S INAUGURAL SEASON AS MUSIC DIRECTOR OF THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA BEGINS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2012, WITH A GALA CONCERT FEATURING THE INCOMPARABLE RENÉE FLEMING Opening Weeks of Nézet-Séguin’s Tenure to Feature Verdi’s Requiem, His Carnegie Hall Debut, and Concerts with Violinist Joshua Bell (Philadelphia, October 18, 2012)—Yannick Nézet-Séguin officially begins his tenure as The Philadelphia Orchestra’s eighth music director with a gala Opening Concert on October 18, 2012, two weeks of subscription concerts at the Orchestra’s home in Verizon Hall at the Kimmel Center, and with his Carnegie Hall debut on October 23 in New York City. Nézet-Séguin was named music director designate of the legendary ensemble in 2010. The gala concert, featuring soprano Renée Fleming, includes Ravel’s Shéhérazade, Brahms’s Symphony No. 4, and “Mein Elemer!” from Arabella by Richard Strauss. For the Orchestra’s first subscription series at the Kimmel Center and for his Carnegie Hall debut, Nézet-Séguin has chosen Verdi’s Requiem, featuring soprano Marina Poplavskaya, mezzo-soprano Christine Rice, tenor Rolando Villazón, bass Mikhail Petrenko, and the Westminster Symphonic Choir. Philadelphia Orchestra Association President and CEO Allison Vulgamore said, “This is the launch of a new chapter for The Philadelphia Orchestra. We have been anticipating this moment for what seems a very long time, and the entire organization couldn’t be more thrilled that it is finally upon us.