Rehabilitation Guidelines for Historic Adobe Structures in Northern New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Inventory

N. H. L. - ARCHITECTURE IN THE PARKS Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES •• COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS_____ NAME HISTORIC Bandelier Buildings and Friloles Canyon Lodge__________________ AND/OR COMMON Bandelier National Monument CCC Historic District (Preferred') LOCATION STREET & NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Bandelier National Monument VICINITY OF 3 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New M 35 Los Alamos and Sandoval Q28 and Q&3 CLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _3jDISTRICT X_PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE. -XMUSEUM _BUILD ING(S) —PRIVATE -.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH -WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _.IN PROCESS %YES. RESTRICTED ^-GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED -XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -NO —MILITARY Q AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS. National Park Service Southwest Regional Office STREET & NUMBER P. 0. Box 728 CITY, TOWN STATE Santa Fe VICINITY OF New Mexico LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. National Park Service Southwest Regional Office STREET & NUMBER P.O. Box 728 CITY. TOWN STATE Santa Fe New Mexico REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE List of Classified Structures Inventory DATE 1984 X.FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D. C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED X.UNALTERED 2LORIGINALSITE X.GOOD _RUINS siALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Bandelier CCC Historic District contains 31 buildings all of pueblo revival design executed with a solid architectural unity that -romantically -mimicked a small New Mexican village. -

Bamboo House Building Manual

Manual on Building Bamboo Houses This manual on how to build a bamboo house comes as a result of research conducted at the Engineering Structures Research Centre at City University by a team of development engineers funded by Pell Frischmann Consulting Engineers. The purpose of their research is to help communities where this kind of information is not accessible and yet the most valuable. The aim of the information provided here is to share knowledge on how to construct low-rise housing that is resistant to earthquakes, particularly in developing countries. The design plans produced by this team require only basic construction skills and tools. The materials are sustainable, durable, and can often be locally obtained. The development team is headed by Professor Kuldeep S. Virdi of City University, London, and Mr. Rossen D. Rashkoff. We appreciate their efforts and commitment to making safe and sustainable housing more accessible. Building materials 1. Introduction The construction materials for building a bamboo house should be readily available and accessible. Traditionally used construction materials are considered. The bamboo based house has a very low weight therefore foundations can be minimised. For wall construction are used wall panels, assembled from split bamboo grids and chicken steel mesh and plastered with cement mortar. Basic materials for house components (bamboo, wire, bolts, chicken mesh, and cement) are inexpensive. Bamboo can tolerate high values of deformations in the elastic range i.e. possesses high elasticity. Therefore bamboo houses when properly constructed are ductile i.e. being able to sway back and forth during an earthquake, without any damage to the bamboo poles. -

Improved Adobe Mudbrick in Application – Child-Care Centre Construction in El Salvador

13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering Vancouver, B.C., Canada August 1-6, 2004 Paper No. 705 IMPROVED ADOBE MUDBRICK IN APPLICATION – CHILD-CARE CENTRE CONSTRUCTION IN EL SALVADOR Dominic DOWLING1 SUMMARY Major earthquakes in Latin America, Asia and The Middle East have served as recent reminders of the vulnerability of traditional adobe (mudbrick) dwellings to the force of earthquakes. A host of research, training and construction projects continue to address this precarious situation and there have been various publications describing the developments in improved adobe (mudbrick) design and construction in recent years. These publications have mostly originated from research institutions and have tended to focus on the technical and experimental details of a variety of improvement systems. The dissemination of this important information is a vital component in the challenge to promote and build safer homes. Furthermore, these advances in technical detail must be accompanied by practical information, which relates to the actual application of the proposed systems, addressing the advantages and disadvantages of each technique. This paper attempts to address the current deficiency of this practical information, and thus provide adobe constructors and proponents with a realistic understanding of some of the practical issues related to improved adobe construction. This paper describes the technical and practical aspects and ‘lessons learned’ from a recent improved adobe construction project in El Salvador, as well as drawing on field investigations, laboratory research and other literature. The paper concludes with a proposed addition to the current technical evaluation of the performance of improvement systems: the assessment of the skill level and resources required to effectively incorporate improved adobe systems. -

Comparison of Adobes from Pre-History To-Date

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 12 (2017) 437–448 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep Comparison of adobes from pre-history to-date Maria Costi de Castrillo, Maria Philokyprou, Ioannis Ioannou ⁎ School of Engineering, University of Cyprus, 75 Kallipoleos Av., P.O. Box 20537, 1678 Nicosia, Cyprus article info abstract Article history: This paper presents a comparative study between prehistoric, traditional (19th–20th century) and contemporary Received 23 September 2016 adobe bricks from Cyprus. Reported experimental results include grain size distribution analyses, qualitative and/ Received in revised form 7 February 2017 or quantitative mineralogical and chemical analyses, methylene blue and Atterberg Limits tests of the raw mate- Accepted 9 February 2017 rial used for the production of the aforementioned adobes. The experimental results are complemented by a thor- Available online xxxx ough literature review of Cypriot adobe production. fi Keywords: The ndings of the study show that contemporary as well as traditional adobes are to a great extent similar to the Adobe prehistoric ones tested in the framework of this research, taking into account the inherent non-homogeneity of Prehistory the material. This conclusion derives both from the literature review and from the tests conducted in the labora- Raw material tory. Although similarities are evident in the principles of production and curing, there are differences in the ac- Physico-chemical properties tual composition and mix design that may potentially influence the physico-mechanical characteristics and durability of adobe bricks. It is anticipated that the investigation of early adobe samples and the comparison of traditional methodologies and practices of adobe production with respective contemporary ones, will contribute towards the enhancement of existing knowledge regarding adobe production technology. -

Adobe: an Ancient Folk Technology by Peter Nabokov

Adobe: An Ancient Folk Technology By Peter Nabokov In the ancient world, Arabs mixed sand, clay, water, and a vegetal binding Peter Nabokov is a Research Associate for the material to make al-tob. The Spanish, principally because of contact with the Museum ofthe American Indian. He has writ ten extensively, his most recent work being, Arabic Moors of North Mrica, knew the process and called it adobe. When they Native American Testimony: An Anthology of arrived in the New World, the Spanish colonists found that the Indians in the Indian and White Relations. Forthcoming works Southwest had been using the same process for centuries. Today, we still know it include Native American Architecture to be by its Spanish name: adobe. published in 1982 by Oxford University Press with Robert Easton; and Indian Running, a It is not surprising that the Spanish and Indians shared an affinity for building study ofritual and athletics throughout the with adobe. The basic materials used to make it were common to both Americas, to bepublished this fall by Capra continents. In addition, it had unique qualities that made it an ideal building Press. material for arid climates. During the day, adobe absorbed the heat of the sun, leaving the house interior much cooler than the outside. As the outside air cooled in the evening, the walls reflected the stored heat into the houses, taking the chill off the night air. Adobe was also an infinitely adaptable construction medium: it could be shaped in many forms to meet a wide range of social, cultural, and physical housing needs. -

A Dobe C Onserva Tion a P R E S E R V a T I O N H a N D B O O K

A DOBE C ONSERVA TION A P R E S E R V A T I O N H A N D B O O K by THE TECHNICAL STAFF of CORNERSTONES COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS with illustrations by FRANCISCO UVIÑA CONTRERAS santa fe Adobe Conservation - a Preservation Handbook has been compiled by Cornerstones Community Partnerships, a 501(c)3 organization based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Since 1986, Cornerstones Community Partnerships has worked to preserve architectural heritage and community traditions in New Mexico and the Southwest. Cornerstones has assisted more than 300 rural communities preserve historic earthen structures by teaching tradi- tional building skills and engaging youth and elders in the process of understanding and maintaining their cultural connection to earthen architecture. Youth training and applied learning have proven to be key factors in historic preservation in New Mexico and the Southwest, where the labor-intensive nature of traditional building methods poses unique challenges. Cornerstones is committed to working in partnership with communities to preserve historic resources, encourage traditional building practices and affirm cultural values. Tax-deductible contributions may be sent to Cornerstones Community Partnerships, P.O. Box 2341, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 87501-2341. Funding for this publication was generously provided by the Historic Preservation Division of the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs, by the Santa Fe Community Foundation and by the New Mexico Historical Society. © 2006 by Cornerstones Community Partnerships. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Adobe conservation : a preservation handbook / compiled by the technical staff of Cornerstones Community Partnerships ; with illustrations by Francisco Uviña Contreras. -

Van Ayanis” Fort Temple Area and Documentation of Adobe (Mud-Brick ) Buildings Material for Conservation Purposes

Gazi University Journal of Science GU J Sci 28(3):433-444 (2015) Restoration Project for “Van Ayanis” Fort Temple Area and Documentation of Adobe (Mud-Brick ) Buildings Material for Conservation Purposes Ali Çetin İDİL1,♠, Mehmet IŞIKLI2, Alper GÜRER3, Derya GÜRER4 1Şeyh Şamil Mah. 180. Sk 17338 ada C4/5 Daire 3 Eryaman, Ankara/TÜRKİYE 2Atatürk Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Arkeoloji Bölümü, Protohistorya ve Önasya Arkeolojisi A.B.D. 25240 Erzurum/TÜRKİYE 3Ordu Blv. Turunç Apt. No:40/3 Afyonkarahisar /TÜRKİYE 4Ordu Blv. Turunç Apt. No:40/3 Afyonkarahisar /TÜRKİYE Received: 01/07/2014 Revised: Accepted:14/01/2015 ABSTRACT The target of this study is to systematically collect soil based adobe blocks that are obtained as the result of the excavations and to develop the methods of examination of that material. In line with this target, within the scope of the restoration project for the temple, which has been exposed in Ayanis Fort excavations, which is 500 m northern of Van Province, Ayanis/Ağartı Village, the geological and chemical structure of the soil based adobe blocks has been analyzed with SEM/EDS and XRD methods, the adobe material combination has been interpreted and preliminary intervention principles and restoration project have been prepared for the excavation pits with the purpose of in-situ conservation/ freezing. Keywords: Van, Ayanis, Ağartı, Fort, Soil, Clay, SEM/XRD, Adobe, Material. 1. INTRODUCTION performed in the past years, by using two samples. The geological and chemical structures of those soil based The roots of the buildings, which are constructed with adobe blocks have been analyzed with SEM/EDS and soil based adobe building material, in which XRD methods and the combination of adobe bricks has approximately 30-40% of the world population is still been interpreted. -

A Dobe C Onserva Tion a P R E S E R V a T I O N H a N D B O O K

A DOBE C ONSERVA TION A P R E S E R V A T I O N H A N D B O O K by THE TECHNICAL STAFF of CORNERSTONES COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS with illustrations by FRANCISCO UVIÑA CONTRERAS santa fe Adobe Conservation - a Preservation Handbook has been compiled by Cornerstones Community Partnerships, a 501(c)3 organization based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Since 1986, Cornerstones Community Partnerships has worked to preserve architectural heritage and community traditions in New Mexico and the Southwest. Cornerstones has assisted more than 300 rural communities preserve historic earthen structures by teaching tradi- tional building skills and engaging youth and elders in the process of understanding and maintaining their cultural connection to earthen architecture. Youth training and applied learning have proven to be key factors in historic preservation in New Mexico and the Southwest, where the labor-intensive nature of traditional building methods poses unique challenges. Cornerstones is committed to working in partnership with communities to preserve historic resources, encourage traditional building practices and affirm cultural values. Tax-deductible contributions may be sent to Cornerstones Community Partnerships, P.O. Box 2341, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 87501-2341. Funding for this publication was generously provided by the Historic Preservation Division of the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs, by the Santa Fe Community Foundation and by the New Mexico Historical Society. © 2006 by Cornerstones Community Partnerships. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Adobe conservation : a preservation handbook / compiled by the technical staff of Cornerstones Community Partnerships ; with illustrations by Francisco Uviña Contreras. -

Jornada Mogollon

National Park Service White Sands U.S. Department of the Interior White Sands National Monument Jornada Mogollon Archaeologists use broken pieces of pottery to identify Jornada Mogollon sites. (NPS Photo) he people who made pottery, lived in permanent houses, and farmed the Tularosa Basin are known as the TJornada Mogollon, a name given to them by archeologists. Evidence of their prehistoric presence dates back to about 200 C.E. (Common Era), over 1800 years ago. For 1,200 years, the Jornada Mogollon inhabited the Tularosa Basin, but then something changed. By 1350 C.E. the Jornada Mogollon moved away from the Tularosa Basin, leaving behind puddled adobe and broken pottery sherds. The Jornada Mogollon is the name local resources to make sure they Mogollon hunted: deer, rabbits, archaeologists use to identify the could survive. The most significant and birds. people who lived in the Tularosa technological difference in the Basin after the Archaic period, archaeological record between the We currently know of several which ended almost 2,000 years Archaic to the Jornada Mogollon Jornada Mogollon villages that ago. The Jornada Mogollon was a is the switch from woven fiber existed throughout the Tularosa group of farmers living in houses baskets to clay pottery. Identifying Basin, including two on White in small villages throughout the broken pieces of pottery is one Sands National Monument: Lake southwest. At first, they lived in of the ways archaeologists are Lucero and Huntington Site. pithouses. Pithouses are circular able to identify Jornada Mogollon The sheer number of artifacts houses dug out of the ground and sites. -

Adobe Structures As Our Cultural Heritage and Their Features

European Scientific Journal February 2015 /SPECIAL/ edition vol.1 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 ADOBE STRUCTURES AS OUR CULTURAL HERITAGE AND THEIR FEATURES Selma Tunalı, PhD Maltepe University, Turkey Abstract History indicates that the very first homes were built with the use of natural and local materials. Adobe (which is produced from soil) was an important building material and it was used by the groups that established the first settlements. The archaeological excavations (especially in Anatolia and Mesopotamia) continuously prove this indication. At first, humanity led a life in migrant shelters against the harsh and destructive conditions of the nature, but later gave the most beautiful examples of architecture by using materials that he found in his vicinity. Soil has been used as a building material until today and still continues to be so, especially in Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Yemen, Libya. Soil is a very economical material that can be easily shaped. It can keep its form against natural effects and has a very high temperature and permeability resistance. Technological developments have influenced the whole world and provided numerous conveniences and created many positive effects, however they also brought with them a lot of environmental problems that affect the nature and the mankind. To resolve such problems (such as the change in climatic conditions, the increase in temperature and drought, the extinction of some species), the humanity must design structures that are sensitive to the environment. Considering human health and unification with the nature in a building design that is sensitive to the environment, the most suitable material to provide such qualities would be the soil based adobe which has been used both in rural and urban settlements since the Çatalhöyük Neolitik settlement in Anatolia. -

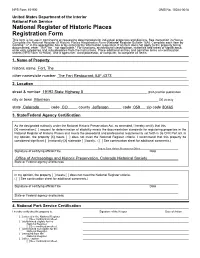

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking ``x'' in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter ``N/A'' for ``not applicable.'' For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Fort, The other names/site number The Fort Restaurant; 5JF.4373 2. Location street & number 19192 State Highway 8 [N/A] not for publication city or town Morrison [X] vicinity state Colorado code CO county Jefferson code 059 zip code 80465 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [X] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant [ ] nationally [X] statewide [ ] locally. -

DOWN to EARTH: the Story of Adobe in New Mexico

DOWN TO EARTH: The Story of Adobe in New Mexico FORMAT: 1 Hour Documentary PRODUCERS: Cathryn Keller Nestor and Mark Freeman SCRIPTWRITER: Rudolfo Anaya BUDGET: $233,700 TO BE RAISED: $228,700 DISTRIBUTION: National Broadcast, Educational Venues and Home Video SUMMARY DOWN TO EARTH, a one hour documentary, is a history of earthen architecture in New Mexico, the meeting place of Native American, Hispanic and Anglo cultures. From the soil itself people have fashioned distinct ways of being in the world. Earthen construction is not just a building technique. Its formal and structural aspects cannot be divorced from its social, cultural and environmental functions. The program examines the relationship between the built environment and the cultural traits, which distinguish each of the major communities in New Mexico. These include the role of religion, ritual and custom; the importance of families and kinship (including gender roles); and the relationship of the community to the larger society and to the natural environment. These concerns will be addressed as they are reflected in and symbolized by earthen architecture--vernacular and professional; sacred and mundane; domestic and institutional; traditional and innovative. Native American architecture in New Mexico originated as a distinctly indigenous art form, a direct response to the American western landscape. Hispanic missionaries and settlers combined adobe and European architectural concepts. Today Spanish Pueblo Style architecture continues as a living tradition serving as the basis for thoroughly contemporary design and innovation. DOWN TO EARTH will incorporate a variety of distinct voices. Historians, folklorists, anthropologists, architects, archaeologists, owner-builders, artists, community leaders, experts and amateurs, all will be heard from.