Greater Vancouver Economic Scorecard 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCHEDULE B – RECOGNIZED PRACTICAL NURSING EDUCATION PROGRAMS (Sections 88, 91, 93) ______

SCHEDULE B – RECOGNIZED PRACTICAL NURSING EDUCATION PROGRAMS (Sections 88, 91, 93) ___________ Educational Institution Campus Program Type Camosun College Victoria Generic CDI College Richmond Generic CDI College Surrey Generic Coast Mountain College Terrace Access College of New Caledonia Burns Lake Generic College of New Caledonia Prince George Generic College of the Rockies Cranbrook Generic Discovery Community College Campbell River Generic & Access Discovery Community College Nanaimo Generic & Access Nicola Valley Institute of Technology Merritt Access North Island College Campbell River Generic North Island College Port Alberni Generic Northern Lights College Dawson Creek Generic Okanagan College Kelowna Generic Okanagan College Penticton Generic Okanagan College Salmon Arm Generic Okanagan College Vernon Generic Sprott Shaw College Abbotsford Generic Sprott Shaw College Downtown Vancouver Generic & Access Sprott Shaw College East Vancouver Generic & Access Educational Institution Campus Program Type Sprott Shaw College Kamloops Generic & Access Sprott Shaw College Kelowna Generic & Access Sprott Shaw College New Westminster Generic & Access Sprott Shaw College Penticton Generic & Access Sprott Shaw College Surrey Generic Sprott Shaw College Victoria Generic Stenberg College Surrey Generic Thompson Rivers University Williams Lake Generic University of the Fraser Valley Chilliwack Generic Vancouver Career College Abbotsford Generic Vancouver Career College Burnaby Generic Vancouver Community College Vancouver (Broadway) Generic & -

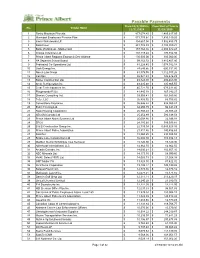

06-Payables Payments Report June-2021.Xlsx

Payables Payments From 6/1/2021 to From Start of Year to No. Vendor Name 6/30/2021 6/30/2021 1 PCL Construction Management Inc. $1,432,098.00 $4,202,885.16 2 Municipal Employees Pension Plan $865,122.32 $3,933,810.39 3 B & B Construction Group Inc. $413,794.41 $794,413.84 4 McDougall Gauley LLP $380,625.00 $380,625.00 5 JM Cuelenaere Library $355,457.00 $1,236,287.50 6 Raymax Equipment Sales Ltd. $294,232.28 $300,742.28 7 Saskatchewan Public Safety Agency $257,934.39 $812,357.75 8 Bank of Montreal - Mastercard $235,761.82 $1,144,650.98 9 SaskPower $191,693.85 $1,372,551.60 10 PA Separate School Board $137,484.12 $1,042,959.53 11 Emco Corporation $130,617.21 $279,969.15 12 AECOM Canada Ltd. $105,243.91 $433,914.10 13 Federated Co-Operatives Ltd. $102,688.03 $523,979.85 14 Community Service Centre $101,201.68 $354,205.88 15 Flocor $99,679.69 $161,309.91 16 Associated Fire Safety Group $86,413.50 $86,413.50 17 Novus Law Group $84,897.69 $282,297.38 18 Klearwater Equip & Technologies $79,336.00 $194,037.80 19 SPCA $75,660.01 $238,437.35 20 Iconix Waterworks LP $73,376.22 $151,087.79 21 Wheatland Builders & Concrete Ltd. $64,728.30 $221,492.63 22 Prince Albert Regional Economic Dev Alliance $61,250.00 $183,750.00 23 Group2 Architechture Engineering Inc $50,902.85 $397,732.08 24 Line West Ltd. -

Twenty-Four/Sevenoctober 18, 2010 Volume 5, Issue 23

October 18, 2010 Volume 5, Issue 23 CLARKtwenty-four/seven CLARKtwenty-four/seven Table of Contents October 18, 2010 Notes from the Smiles All Around Meet Your New Upcoming Events 2 Summit White 5 Dental Hygiene 7 Ambassadors! 12 House Summit on Anniversary Student Community Colleges Ambassadors From the HR A Voice from History 13 Department Breakfast for 6 David Hilliard speaks Penguin Patter 3 Champions on Black Panthers 10 News about people Advisory Committee from throughout the recognition Penguin Nation! Cover: Dean of Health Sciences Blake Bowers 2 and Associate Director of Instructional Operations Dedra Daehn attend the Advisory Committee Recognition Breakfast on Friday, October 15. 5 14 3 1 Notes from the Summit Clark hosts webcast of first-ever White House Summit on Community Colleges. “Community colleges are the unsung heroes of higher education.” That was a key message as President Obama convened the first White House Summit on Community Colleges on Tuesday, October 5. The event was led by Dr. Jill Biden, who has been a community college professor for 17 years. Among the highlights: • The administration has announced a new partnership called “Skills for America’s Future.” It’s designed to change the way business and labor leaders connect to community colleges. • President Obama has set a goal for America to once again lead the world in producing college graduates by 2020. That includes an additional 5 million community college degrees and certificates in the next 10 years. • The Bill and Melinda Gates foundation are launching the “Completion by Design” program. Investing $35 million over five years, the program hopes In a phrase that has special meaning at Clark College, two of the speakers— to dramatically improve graduation rates at community colleges. -

The Fastest 50 the Vancouver Sun Wed 31 Oct 2007 Page: F2 Section: Special Section Source: Vancouver Sun

The Fastest 50 The Vancouver Sun Wed 31 Oct 2007 Page: F2 Section: Special Section Source: Vancouver Sun British Columbia's fastest-growing publicly traded companies These lists detail two pillars of B.C.'s economy: Those companies with the fastest growth and those companies with the strongest fundamentals, hence the Fastest 50 and the Strongest 50 combine to form The Vancouver Sun's Top 100. The Fastest list is all about balanced growth, not just success in one category of financial performance. Where other ranking efforts look solely at revenue change, BusinessBC's sophisticated analysis is based on formulas developed by James Brander of the Sauder School of Business at the University of British Columbia. It takes into account employee growth, revenues, stock performance, and earnings. The Strongest 50 concentrates on total assets, market capitalization and how the company performs based on those fundamentals (more below.) Twenty-five companies, such as Teck Cominco, have both strong fundamentals and continue to grow, so they qualify for both lists. BusinessBC's other project partner, Ernst & Young LLP, began by looking at all publicly-traded companies with headquarters in B.C. and/or a significant proportion of business activities located in the province. Most but not all companies are traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange or the TSX Venture Exchange. Detailed financial information was drawn from annual reports and other sources. Employee numbers were volunteered by the companies and compiled by staff at The Vancouver Sun. Some 500 to 600 corporations were reviewed to arrive at this selection. James Brander's formula was applied to Ernst & Young's findings and the result was further refined to ensure that companies with balanced growth across the categories received due recognition. -

SPROTT SHAW COLLEGE Be Kind

SPROTT SHAW COLLEGE Be Kind. Be Calm. 2021 Be Safe. GRADUATION - Dr. Bonney Henry BE AMAZING! - Sprott Shaw College ORDER OF CEREMONY VALEDICTORIANS Processional Amanda McGregor Desiree Rouw-McCarron Abbotsford Penticton Business Administration Bookkeeping Practical Nursing National Anthem Mellissa Kimberley Chilliwack Sultana Sazia Afrin Special Education Teaching Assistant Richmond Early Childhood Education Master of Ceremonies Shane Gibson Jeunice Cyrille Ciruela Keynote Speaker, Author & Sales Trainer East Vancouver Mark Jayvin D. Manlapaz Practical Nursing Access Surrey President’s Address Victor Tesan Early Childhood Education President Bronwyn Beach Kamloops Sara Kohan Practical Nursing Access Vancouver Pender Speaker Krista Thompson Tourism and Hospitality Management Chief Executive Officer Keegan Mosher Conventant House Vancouver Kelowna Practical Nursing Mary Jane Igharas Premiers Address John Horgan Vancouver Seymour Tourism and Hospitality Management Premier, Lucy Evans British Columbia Maple Ridge Medical Office Assistant Health Unit Clerk Jennifer Celeste Valedictorians Address By Campus Victoria Taylor Gates Early Childhood Education Nanaimo Health Care Assistant Convocation Congratulations Class of 2021 Presentation Julia Bui New Westminster Business Administration Bookkeeping SPECIAL MESSAGES A MESSAGE FROM August, 2021 PREMIER JOHN HORGAN A Message from the Mayor As Premier of British Columbia I extend my warmest greetings to everyone taking part On behalf of Vancouver City Council, I wish to extend my sincere congratulations to the in the virtual Sprott Shaw College 2021 Graduation Ceremonies. 2020/2021 Graduating class of Sprott Shaw College. Sprott Shaw College has an outstanding record of academic performance, as the These ceremonies are an important way of connecting students with their loved ones to achievements of its graduates demonstrate. I know fulfilling your career goals has celebrate reaching this exciting milestone. -

Metro Vancouver Language Regional Meeting AGENDA October 20, 2016

Metro Vancouver Language Regional Meeting AGENDA October 20, 2016 | 9:00 a.m. – 3:30 p.m. Executive Hotel and Conference Centre 4201 Lougheed Hwy, Burnaby, BC V5C 3Y6 Room: Panorama SERVICE PROVIDER ORGANIZATIONS (SPO) Louise Thorburn, Burnaby Continuing Education (School District No. 41) Mark Batt, Burnaby/New West English Language Centres Marcela Mancilla-Fuller, Collingwood Neighbourhood House Alison Whitmore, Coquitlam Continuing Education (School District No. 43) Mary Daniel, Douglas College Rajeeta Samala, Collège Éducacentre College Ewa Karczewska, ISS of BC (Coquitlam) Eysa Alvarez, ISS of BC (New West/Burnaby/Cottonwood) Katie Graham, ISS of BC (Richmond) Tara Ramsey, ISS of BC (Squamish) Diana Smolic, ISS of BC (Vancouver) Lisa Herrera, ISS of BC (Vancouver) Carla Morales, ISS of BC (Vancouver) Susan Schachter, Little Mountain Neighbourhood House Chantelle MacIsaac, MOSAIC (Brentwood) Diana Ospina, MOSAIC (Vancouver) Linda Davies, MOSAIC (Vancouver) Anita Schuller, MOSAIC/North Shore Multicultural Society Barbara Anne Steed, Richmond - Blundell Adult Learning Centre (School District No. 38) Ryan Drew, S.U.C.C.E.S.S. Shae Viswanathan, S.U.C.C.E.S.S. (Tri-Cities) Elise Emnacen, S.U.C.C.E.S.S. (Richmond) Aaron Kilner, S.U.C.C.E.S.S. (Vancouver) Jessica Hannah, S.U.C.C.E.S.S. (Vancouver) Wei Wei Siew, South Vancouver Neighbourhood House Janet Theny, Vancouver Community College Julia Tajiri, Vancouver Formosa Academy Wes Schroeder, Western ESL Services IMMIGRATION, REFUGEES and CITIZENSHIP CANADA (IRCC): Cindy Wong, Manager, Integration, -

Negotiating a Quantum Computation Network: Mechanics, Machines, Mindsets

Negotiating a Quantum Computation Network: Mechanics, Machines, Mindsets by Derek Noon A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016, Derek Noon Abstract This dissertation describes the origins, development, and distribution of quantum computing from a socio-technical perspective. It depicts quantum computing as a result of the negotiations of heterogeneous actors using the concepts of ANT and socio-technical analyses of computing and infrastructure more generally. It draws on two years of participant observation and interviews with the hardware and software companies that developed, sold, and distributed both machines and a mindset for a new approach to computing: adiabatic quantum computation (AQC). It illustrates how a novel form of computation and software writing was developed by challenging and recoding the usual distinctions between digital and analogue computing, and discusses how the myriad controversies and failures attending quantum computing were resolved provisionally through a series of human and non-human negotiations. These negotiations disrupted, scrambled, and reconstituted what we usually understand as hardware, software, and mindset, and permitted a ‗disruptive‘ technology to gain common acceptance in several high profile scientific, governmental, and financial institutions. It is the relationalities established across these diverse processes that constitute quantum computing, and consequences of this account of computation are considered in the context of digital media theory, industrial histories of computing, and socio-technical theories of technological innovation. Noon ii Acknowledgements Many sources of support helped me through the PhD program. I‘m grateful to Mitacs for its financial support of this research, and for providing me such good STEM peers/research subjects. -

Expiring Contracts January 1, 2021 — December 31, 2021 Contract Company Union Expiry

Volume 53, Issue 1, Feb/Mar 2021 EXPIRING CONTRACTS JANUARY 1, 2021 — DECEMBER 31, 2021 CONTRACT COMPANY UNION EXPIRY PRIVATE SECTOR United Food & Commercial Workers Rossdown Farms and Natural Foods 2021-01-24 Union AJ Forsyth (Russell Metals) United Steelworkers 2021-01-31 Coast Coal Harbour Hotel Unifor 2021-01-31 Ideal Gear and Machine Works United Steelworkers 2021-01-31 Mitchell Press Unifor (MediaUnion) 2021-01-31 Ringball Corporation and Vanguard United Steelworkers 2021-01-31 Steel Ltd. British Columbia Government & Servomation/Centerplate Inc. 2021-01-31 Service Employees' Union The Hudson's Bay Company United Steelworkers 2021-01-31 British Columbia Government & Union Bay Credit Union 2021-01-31 Service Employees' Union British Columbia Government & Canadian Diabetes Association 2021-02-17 Service Employees' Union British Columbia Government & Freshwater Fisheries Society 2021-02-17 Service Employees' Union Marine Workers and Boilermakers Allied Shipbuilders Limited Industrial Union Local 1, Pipe Fitters 2021-02-28 UA, Local 170, IBEW Local 213 Interior Savings Credit Union British Columbia Government & 2021-02-28 (Thompson) Service Employees' Union International Union of Operating Lafarge Asphalt Technologies 2021-02-28 Engineers International Brotherhood of Seaspan Victoria Shipyards Co Ltd. 2021-02-28 Boilermakers Sprott Shaw Language (formerly KGIC Education and Training Employees' 2021-02-28 Language College) Association Cascade Aerospace Unifor 2021-03-30 IATSE 891, Teamsters 155, BC and Yukon Council of Film Unions International -

The Lower Mainland Food System: the Role of Fruit and Vegetable Processing

The Lower Mainland Food System: The Role of Fruit and Vegetable Processing by Grant Rice B.Comm., Royal Roads University, 2008 Research Project Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Urban Studies in the Urban Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Grant Rice 2014 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2014 Approval Name: Grant Rice Degree: Master of Urban Studies Title of Thesis: The Lower Mainland Food System: The Role of Fruit and Vegetable Processing Examining Committee: Chair: Anthony Perl Professor, Urban Studies and Political Science Hannah Wittman Senior supervisor Adjunct Professor, Urban Studies Program, SFU. Associate Professor, Faculty of Land and Food Systems, UBC. Peter Hall Co-supervisor Associate Professor Herb Barbolet External examiner Independent food consultant Date Defended/Approved: January 08, 2014 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Ethics Statement iv Abstract In this paper I explore the transformation of the fruit and vegetable processing industry in BC’s Lower Mainland region from the late 1980s to 2011. I look at how the industry has adapted to the globalization of the fruit and vegetable processing sector and how it has evolved since the introduction of free trade agreements in 1989 and 1994. This research is based on the analysis of media reports, statistical data, survey results, and a series of interviews. The fruit and vegetable processing industry works within a globalized, competitive food system, while remaining an important component of the local food system. The paper contributes to the growing body of literature on Alternative Food Networks and Short Food Supply Chains in an often understudied link in that chain. -

Fish-July-Aug 03

AGREEMENT NUMBER 40012128 VOL. 73NO.2 Season’s Greetings I DECEMBER, 2008 I VANCOUVER, B.C. VANCOUVER, $1 SHOREWORKERS THE FISHERMAN, DECEMBER 2008 2 SAFETY A Merry Christmas NS court decision puts and Happy New Year to all our friends and fishermen. off WorkSafe challenge Thanks for your support in 2008. Appeal Court rules province can Part II (which includes occupa- tional health and safety regula- govern worker safety on boats tions). For fishermen working in company challenge month that the case was “still in provincial jurisdiction in Nova to the jurisdiction of the process” but noted that other Scotia, he said, the Occupational WorkSafeBC on related cases will likely have to be Health and Safety Act effectively A board fishing vessels resolved before the trial judge takes the place of Part II of the has been sidelined by the court brings it forward. He added that it Canada Labour Code. after the Court of Appeal in Nova may come back some time in the “As Mersey Seafoods ... is a Scotia overturned a key ruling new year. provincial undertaking, Part II of that had prompted the challenge Among the other cases is one the Canada Labour Code and the S.M. PRODUCTS (BC)LTD. in the first place. involving ferries, as well as the regulations are replaced by the PROVEN MARKETERS OF NORTH PACIFIC HALIBUT SINCE 1990 Jim Pattison Enterprises, Nova Scotia Court of Appeal rul- Nova Scotia’s OHS Act,” Justice owner of Canadian Fishing ing in the Mersey Seafoods case, Michaud wrote. “But that substi- LONG LINE HALIBUT, Company, and Kevin Smith, which came down last May. -

Vancouver Cross-Border Investment Guide

Claire to try illustration idea as one final cover option Vancouver Cross-Border Investment Guide Essential legal, tax and market information for cross-border investment into Vancouver, Canada Digital Download 1 Vancouver Cross-Border Contents Investment Guide Published October 2020 Why Invest in Vancouver ............................................................................1 Sectors to Watch ........................................................................................... 3 About the Vancouver Economic Commission Technology ..................................................................................................3 The Vancouver Economic Commission (VEC) serves one of the world’s fastest-growing, low- Cleantech .................................................................................................... 4 carbon economies. As the economic development agency for the city’s businesses, investors and citizens, VEC works to strengthen Vancouver’s economic future by supporting local companies, attracting high-impact investment, conducting and publishing leading-edge industry research, Media and Entertainment ............................................................................5 and promoting international trade. VEC works collaboratively to position Vancouver as a global destination for innovative, creative, diverse and sustainable development. Life Sciences ............................................................................................... 6 VEC respectfully acknowledges that it is located -

Payable Payment Report December 2019.Xlsx

Payable Payments From 12/1/2019 to From Start of Year to No. Vendor Name 12/31/2019 12/31/2019 1 Rocky Mountain Phoenix $ 877,674.45 $ 1,485,617.03 2 Municipal Employees Pension Plan $ 573,779.64 $ 7,836,149.25 3 Iconix Waterworks LP $ 334,667.04 $ 3,982,455.79 4 SaskPower $ 281,782.39 $ 3,185,850.21 5 Bank of Montreal - Mastercard $ 157,762.36 $ 2,300,672.48 6 Thorpe Industries Ltd $ 138,119.24 $ 170,852.98 7 Prince Albert Regional Economic Dev Alliance $ 100,000.00 $ 100,000.00 8 PA Separate School Board $ 99,152.72 $ 3,815,407.80 9 Federated Co-Operatives Ltd. $ 81,228.45 $ 1,078,782.18 10 Sask Energy Inc. $ 74,549.56 $ 600,331.80 11 Novus Law Group $ 61,375.95 $ 1,112,017.26 12 CanOps $ 55,921.51 $ 126,676.23 13 Basler Construction Ltd. $ 49,728.00 $ 206,460.00 14 Arctic Refrigeration Inc. $ 49,435.68 $ 305,905.55 15 Clear Tech Industries Inc. $ 45,722.70 $ 673,512.40 16 Playgrounds-R-Us $ 41,445.18 $ 167,340.27 17 Stantec Consulting Ltd. $ 39,956.41 $ 162,585.80 18 Toter, LLC $ 36,803.52 $ 83,793.82 19 Cornerstone Insurance $ 36,546.22 $ 932,953.87 20 Exact Fencing Ltd. $ 34,295.79 $ 94,841.23 21 Sask Housing Corporation $ 25,708.48 $ 25,708.48 22 AECOM Canada Ltd. $ 25,454.99 $ 580,339.53 23 Prince Albert Alarm Systems Ltd $ 25,008.86 $ 32,936.04 24 SPCA $ 24,185.60 $ 389,039.81 25 B & B Construction Group Inc.