A Proposed Football Signal System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of an Offensive Signal System Using Words Rather Than Numbers and Including Automatics

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1958 A study of an offensive signal system using words rather than numbers and including automatics Don Carlo Campora University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Health and Physical Education Commons Recommended Citation Campora, Don Carlo. (1958). A study of an offensive signal system using words rather than numbers and including automatics. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/ 1369 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r, i I l I I\ IIi A ..STUDY OF AN OFFENSIVE SIGNAL SYSTEM USING WORDS RATHER THAN NUMBERS AND INCLUDING AUTOMATICS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Physical Education College of the Pacific In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree .Master of Arts by Don Carlo Campora .. ,.. ' TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION • . .. • . .. • • 1 Introductory statement • • 0 • • • • • • • 1 The Problem • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. 4 Statement of the problem • • • • • • 4 Importance of the topic • • • 4 Related Studies • • • • • • • • • • • 9 • • 6 Definitions of Terms Used • • • • • • • • 6 Automatics • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Numbering systems • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Defense • • • • • • • • • • o- • • • 6 Offense • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Starting count • • • • • • • • 0 6 "On" side • • • • • • • • 0 • 6 "Off" side • " . • • • • • • • • 7 Scouting report • • • • • • • • 7 Variations • • .. • 0 • • • • • • • • • 7 Organization of the Study • • • • • • • • • • • 7 Review of the literature • • • • . -

The Debut of 6-Man Football

The Debut of 6-Man Football at Coeymans High School [CHS] & Ravena High School [RHS] Seasons 1938 - 1943 Prepared by: Chuck Friday September 2008 Dedication Claude B. Friday Coeymans High School Class of 1927 The Debut of 6-Man Football Prologue The introduction of high school football in this community began in 1934 when the Coeymans High School fielded an 11-man team. One year later, Ravena High School [less than 1 mile away from Coeymans High School] introduced its 11-man football squad. Both high schools continued to play 11-man football until the 1938 season. Beginning in 1938 both Coeymans and Ravena high schools converted to the 6-man football format. Each high school had an independent football squad and the rivalry between the two schools was intense. In 1944 Coeymans and Ravena merged their school districts and fielded a single 6-man football team. Local high school football continued using the 6-man format until the 1958 season, when 8-man football was introduced. In the 1963 season 11-man football was, once again, reinstated. This paper attempts to capture some of the early history of 6-man football from the perspective of those years that Coeymans and Ravena competed against each other (i.e., the 1938-1943 seasons). The first three years of competition between these two schools (1938-1940) was captured by a young sports journalist named Fred (Doc) Martino. Shortly after the 1940 football season Fred left his journalist position and enlisted in the military. The last three seasons (1941-1943) that Coeymans and Ravena fielded separate teams are sparsely covered by the local newspaper. -

Yet Do We Love to Toss the Ball of Chance, and in the Relish of Uncertainty, We Find a Spring for Action."

"Yet do we love to toss the ball of chance, And in the relish of uncertainty, We find a spring for action." ATHLETICS THE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION SEATED, LEFT TO RIGHT: Prof. Wyatt Whit- ley, L. W. "Chip" Robert, Prof. Tom Evans, Coach W. A. Alexander, Mr. Charlie Griffin, Jimmy Castleberry, Prof. H. A. Wyckoff, Dean Phil Narmore. STANDING, LEFT TO RIGHT: President Blake Van Leer, Mr. lake Harris, George Brodnax, Al Newton, lack Todd. THE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION WILLIAM A. ALEXANDER, Athletic Director Under the constant vigil of Coach Alexander, Techs athletic facilities have been considerably broadened. from his position as Head Football Coach from 1920 to 1941 he stepped into the role of Athletic Director for the Yellow Jackets. During the past ten years under his guidance, conference championships have fallen to Tech in football, basketball, track, cross country, swimming, fencing, and tennis, while the A.A. has sponsored the first collegiate gymnastic team in the South. In the 1942 poll taken by the Neu . York World-Telegram Coach "Alex" was named "Football Coach of the Year." Coach Alexander is a former president of the American Football Coaches Association and has served as a member of the National Football Rules committee. COACH ROBERT LEE DODD, Hear! Football Coach In 1931 Coach Bobby Dodd came to Georgia Tech to assume his duties as coach of the varsity backfield. varsity baseball, and freshman basketball. His acceptance of these positions followed his nomination the preceding year as All-American quarterback on the University of Tennessee eleven. Upon the retirement of Coach Alexander in 1945, Coach Dood stepped into the position of Head Football Coach at Tech. -

UA19/17/4 Football Program - WKU Vs Morehead State University WKU Athletics

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® WKU Archives Records WKU Archives 10-17-1942 UA19/17/4 Football Program - WKU vs Morehead State University WKU Athletics Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_ua_records Recommended Citation WKU Athletics, "UA19/17/4 Football Program - WKU vs Morehead State University" (1942). WKU Archives Records. Paper 638. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_ua_records/638 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in WKU Archives Records by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STE REH B o W L I N s G D A Y SATURDAY, OCTOBER 17, 1942 - HOWDY FOLKS! HOW YOU rrDOIN~~? AFTER THE " GAME, OR ANY OLD TIME ,"TANK UP" AT SHELLEY PAXTON SERVe STA. 13th and Center ,24 Hour Service Phone 999 After 9 P. M. Phone 359 STANDARD OIL PRODUCTS - "I, ATLAS TIRES-BATTERIES-ACCESSORIES ',' Winterize With The Station That Has Personalized Service. ", I ' • .~ • "i"1 , NOTHING NEW BUT SOMETHING DIFFERENT The Front Cov{!r Wf/$ Designed and Printed by DoN SPENCER COMPANY, INC., 271 Madison Ave., New York. 1942 FOOTBALL SCHEDULE Sept. 26. University of Mississippi . .... .. .. .. Away Oct. 3. Marshall College ... ... .. ... .. .. Home ::: Oct. 9. Youngstown College . .... .. ...... .. Away Oct. 17. Morehead (Dads Day) .. ... .. ........ Home :::Oct. 23. Union University .. .. .. ... ... .. Away Oct. 31. Eastern .. .. .. .. ... .... .. Away Nov. 7. T. P. I. (Homecoming) .. .. .. ... ... .. Home Nov. 14. Union University .... ..... .. ..... ... Home Nov. 21. Murray . .... .. .. .. .. .... Away ::: Night games ~ 1--. 2:J~j ftL 10 () () - "OCTOf»ER DAD~S DAY PROGRAM Football Game 2:30 P. -

Honors & Awards

HONORS & AWARDS 1981 * Morten Andersen, placekicker (TSN, UPI, WC) SPARTAN FIRST-TEAM ALL-AMERICANS * James Burroughs, defensive back (TSN) 1915 #* Neno Jerry DaPrato, halfback (INS, Detroit Times) 1983 * Carl Banks, linebacker (AP, UPI, TSN) Blake Miller, end (Atlanta Constitution) * Ralf Mojsiejenko, punter (TSN) 1930 Roger Grove, quarterback (B) 1985 #* Lorenzo White, tailback (AP, UPI, FWAA, WC, AFCA, TSN) 1935 #* Sidney Wagner, guard (UP, INS, NYS, Liberty Magazine) 1986 * Greg Montgomery, punter (FWAA) 1936 Arthur Brandstatter, fullback (B) 1987 Tony Mandarich, offensive tackle (FN) 1938 * John Pingel, halfback (AP) Greg Montgomery, punter (FN, GNS, MTS) 1949 * Lynn Chandnois, halfback (INS, UP, CP, FN, Collier’s) #* Lorenzo White, tailback (FN, WC, FWAA, GNS, UPI, FCAK, MTS) Donald Mason, guard (PN, FN) 1988 #* Tony Mandarich, offensive tackle #* Edward Bagdon, guard (Look, UP, TSN, NYN, CP, NEA, Tele-News) (AP, UPI, FCAK, WC, FWAA, TSN, GNS, FN, MTS) 1950 * Dorne Dibble, end (Look) Andre Rison, split end (GNS) * Sonny Grandelius, halfback (AP, INS, CP) * Percy Snow, linebacker (TSN) 1951 #* Robert Carey, end (UP, AP, TSN, NEA, NYN, B) 1989 Harlon Barnett, defensive back (TSN, MTS) #* Don Coleman, tackle #* Bob Kula, offensive tackle (FCAK, AP) (AP, UP, Collier’s, Look, TSN, NYN, FN, NEA, CP, Tele-News, INS, CTP, B) #* Percy Snow, linebacker (FCAK, AP, UPI, FWAA, FN, TSN, WC, MTS) * Albert Dorow, quarterback (INS) 1997 * Flozell Adams, offensive tackle (WC) James Ellis, halfback (CTP) Scott Shaw, offensive guard (GNS) 1952 * Frank -

The Ice Bowl: the Cold Truth About Football's Most Unforgettable Game

SPORTS | FOOTBALL $16.95 GRUVER An insightful, bone-chilling replay of pro football’s greatest game. “ ” The Ice Bowl —Gordon Forbes, pro football editor, USA Today It was so cold... THE DAY OF THE ICE BOWL GAME WAS SO COLD, the referees’ whistles wouldn’t work; so cold, the reporters’ coffee froze in the press booth; so cold, fans built small fires in the concrete and metal stands; so cold, TV cables froze and photographers didn’t dare touch the metal of their equipment; so cold, the game was as much about survival as it was Most Unforgettable Game About Football’s The Cold Truth about skill and strategy. ON NEW YEAR’S EVE, 1967, the Dallas Cowboys and the Green Bay Packers met for a classic NFL championship game, played on a frozen field in sub-zero weather. The “Ice Bowl” challenged every skill of these two great teams. Here’s the whole story, based on dozens of interviews with people who were there—on the field and off—told by author Ed Gruver with passion, suspense, wit, and accuracy. The Ice Bowl also details the history of two legendary coaches, Tom Landry and Vince Lombardi, and the philosophies that made them the fiercest of football rivals. Here, too, are the players’ stories of endurance, drive, and strategy. Gruver puts the reader on the field in a game that ended with a play that surprised even those who executed it. Includes diagrams, photos, game and season statistics, and complete Ice Bowl play-by-play Cheers for The Ice Bowl A hundred myths and misconceptions about the Ice Bowl have been answered. -

Woody Hayes; a Case Study in Public Communication, 1973

75-3155 NUGENT, Beatrice Louise, 1943- WOODY HAYES; A CASE STUDY IN PUBLIC COMMUNICATION, 1973. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1974 Speech Xerox University Microfilms,Ann Arbor, Michigan48ice © 1974 BEATRICE LOUISE NUGENT ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED. WOODY HAYES I A CASE STUDY IN PUBLIC COMMUNICATION, 1973 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Beatrice Louise Nugent, B.A., M.A. The Ohio State University 1974 Reading Committeei Approved By Dr. John J. Makay, Adviser Dr. Keith Brooks Dr. James L. Golden Department of Communicamon ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In this space, it would be impossible for me to thank all the people who provided help and encouragement while this work was being prepared. However, I hope I expressed ray sincere appreciation to each along the way. There are those who deserve a special "thank you," though, for without their help and encouragement, it is doubtfiol Tdiether this task could have been completed. Certainly, Coach Hayes and his secretary, Ms, Lena Biscuso, were indispensable. They provided me with information that could not have been acquired elsewhere. Dr. John J, Makay, Chairman of my dissertation committee, provided excellent guidance and gave generously of his time. The other two members of my committee - Dr, Keith Brooks and Dr, James L. Golden - were also most helpful and supportive, I deeply appreciate their efforts. To my parents and family - words are inadequate to fully thank them for the emotional stability they provided. That stability was further enhanced by the constant encouragement of Mrs, Isabelle Pierce and her family and by fellow doctoral candidate, Ms, Jude Yablonsky, TO MY MOM AND DAD March 19, 1 9 ^ 3 ......... -

036-046 Moments in History NO FOOTER.Indd

10 20 30 40 50 40 30 20 10 NFF CELEBRATES 70TH ANNIVERSARY Third Decade Milestones: 1967-1976 1967 1968 THREE U.S. PRESIDENTS CLAIM NFF GOLD: During the NFF’s third decade, one sit- DICK KAZMAIER, the Hall of Famer from Prince- DOLLY COHEN, a well-known philanthropist, ton and 1951 Heisman Trophy winner, serves as the becomes the fi rst woman recognized during ting U.S. president and two future U.S. presidents, all of whom played college football, national chairman of chapters and membership, the NFF Annual Awards Dinner at the Waldorf would accept the NFF Gold Medal, the organization’s highest honor. (From Left) Richard addressing the Seventh Annual NFF Chapter Con- Astoria. NFF Secretary Robert Hall presents the Nixon, a substitute tackle at Whittier College (Calif.), took the NFF stage in 1969. Cal- vention at the New York Racquet Club on Dec. 5 special commendation, which praised her service prior to the 10th NFF Annual Awards Dinner the to the game and youth. Cohen served as pres- ifornia Governor Ronald Reagan, a guard at Eureka College (Ill.), accepted the award same day. Membership continues to grow, dou- ident of the NFF Cincinnati Chapter, donating two years later in 1971, and U.S. House Republican Leader Gerald Ford, a star center and bling from 2,300 to 5,326 in two and a half years. thousands of dollars to the organization as one of Kazmaier would later serve as NFF Awards Chair- the original supporters. She passed away in 1970, linebacker at Michigan, received the medal in 1972. -

Notre Dame Scholastic Football Review

WORDEN PETiTBON OSTROWSKI HUNTER HOWMAIIYTIMESAMY DOYOUINHAIE? 50?] (iOO?H200? IF YOU'RE AH AVERAGE SMOKER THE RIGHT AHSWER IS OVER 200! Yes, 200 times every day your nose ond throat are exposed to irritation... 200 GOOD REASONS WHY YOU'RE BEHER OFF SiNOiaNG PHILIP MORRIS! PROVED definitely milder . PROVED definitely less irritating than any other leading brand . PROVED by outstanding nose and throat specialists. YES, you'll be glad tomorrow . .. you smoked PHILIP MORRIS today! CALL FOR PHILIP MORRIS Football Review e P**' .. ///, / ^ AT INDIANA TYPESETTING CORPORATION 211 SERVICE COURT •SOUTH BEND 1, INDIANA In South Bend GILBERT'S is th^ place to go for the names you know. — TAKE THE MICHIGAN STREET BUS \ \ \STATE GILBERT'S 813-817 S. Michigan Si. Open every evening till 9 December 7, 1951 but Cigars are a ^an!; Smoke! Y>u need not inhale to ei^oy a cigar/ CIGAR INSTITUTE OF AMERICA, INC. The Manhattan Shirt Company, makers of Manhattan shirts, neck wear, undertvear, pajamas, sportshirts, beachwear and handkerchiefs. Football Review 107 N. D. MEN DID IT You Can Do It Too! SAVE TIME The records of 107 Notre Dame men who have BETTER READING means reading faster, understanding completed our training show: more of what you read, knowing how to approach various kinds of reading and how to get the most out average reading rate before training 292 WPM of it in the shortest time. average reading rate after training 660 WPM You can do all your reading in half the average comprehension before training 81 % time it takes you now. -

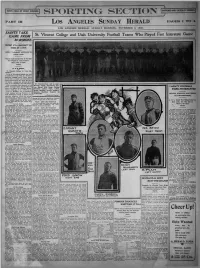

Sporting Section Gathered and Editedby Experts

EVERY FIELD OF SPORT COVERED SPORTING SECTION GATHERED AND EDITEDBY EXPERTS PART 111 Los Angeles Sunday Herald. PAGES 1 TO 4 LOS ANGELES HERALD: SUNDAY MORNING, NOVEMBER 3, 1907. SAINTS TAKE Fast Interstate Game GAME FROM St. Vincent College and Utah University Football Teams Who Played MORMONS DEFEAT UTAH UNIVERSITY BY SCORE OF 11 TO 5 REBULT PLEASANT SURPRISE TO LOCAL FANS Experts Call Contest One of the Best Ever Played on Local Gridiron. Heavy Men on Both Teams R. M. BEERE St. Vtocent'a College 11, Utah TJnl- vernltr 5. Inone of the greatest games ever seen in California or the west, St. Vincent's yestarday dragged proud Utah's colors In the dust of defeat and demonstrated beyond peradventure of a doubt that it Is the fastest, headiest and grittiest eleven west of the Mississippi river this season. St. Vincent—From left to right: ¦ After conquering every opponent In the Brinkop, Taylor, Rheinschild, Mur-] Hocky mountain region for the last two 1 VARSITYFOOTBALL ray, Stonoy, Gait, Casey, Phillips,' years and taking tho Colorado Miners' Holleran, Lamer, Kelm, Leffert, ecalps week U., to the WORK INTERRUPTED - a ago, U. trained Bourg, Brannen, Grlndle (captain), 1 Inute by Maddock, one of America's Beatson, Dechman, Huppert, De ', wisest coaches, met Its Waterloo In a Yuberrando — HOLMES' SCHEDULE BHATTERED most humiliating at park by manner Fiesta I>lio<<> Vincent . yesterday afternoon before 5000 rooters. BY CIRCUMSTANCES The stand blaze was a of color! and a through guard, birt Russell of femininity added beauty to the St. Vincent's mass missed the goal kick In the first scene. -

NCAA Division I Football Records (Coaching Records)

Coaching Records All-Divisions Coaching Records ............. 2 Football Bowl Subdivision Coaching Records .................................... 5 Football Championship Subdivision Coaching Records .......... 15 Coaching Honors ......................................... 21 2 ALL-DIVISIONS COachING RECOrds All-Divisions Coaching Records Coach (Alma Mater) Winningest Coaches All-Time (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct.† 35. Pete Schmidt (Alma 1970) ......................................... 14 104 27 4 .785 (Albion 1983-96) BY PERCENTAGE 36. Jim Sochor (San Fran. St. 1960)................................ 19 156 41 5 .785 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four-year colleges (regardless (UC Davis 1970-88) of division or association). Bowl and playoff games included. 37. *Chris Creighton (Kenyon 1991) ............................. 13 109 30 0 .784 Coach (Alma Mater) (Ottawa 1997-00, Wabash 2001-07, Drake 08-09) (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct.† 38. *John Gagliardi (Colorado Col. 1949).................... 61 471 126 11 .784 1. *Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) ........................ 24 289 22 3 .925 (Carroll [MT] 1949-52, (Mount Union 1986-09) St. John’s [MN] 1953-09) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) ......................... 13 105 12 5 .881 39. Bill Edwards (Wittenberg 1931) ............................... 25 176 46 8 .783 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Case Tech 1934-40, Vanderbilt 1949-52, 3. Frank Leahy (Notre Dame 1931) ............................. 13 107 13 9 .864 Wittenberg 1955-68) (Boston College 1939-40, 40. Gil Dobie (Minnesota 1902) ...................................... 33 180 45 15 .781 Notre Dame 41-43, 46-53) (North Dakota St. 1906-07, Washington 4. Bob Reade (Cornell College 1954) ......................... 16 146 23 1 .862 1908-16, Navy 1917-19, Cornell 1920-35, (Augustana [IL] 1979-94) Boston College 1936-38) 5. -

The Wild Bunch a Side Order of Football

THE WILD BUNCH A SIDE ORDER OF FOOTBALL AN OFFENSIVE MANUAL AND INSTALLATION GUIDE BY TED SEAY THIRD EDITION January 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION p. 3 1. WHY RUN THE WILD BUNCH? 4 2. THE TAO OF DECEPTION 10 3. CHOOSING PERSONNEL 12 4. SETTING UP THE SYSTEM 14 5. FORGING THE LINE 20 6. BACKS AND RECEIVERS 33 7. QUARTERBACK BASICS 35 8. THE PLAYS 47 THE RUNS 48 THE PASSES 86 THE SPECIALS 124 9. INSTALLATION 132 10. SITUATIONAL WILD BUNCH 139 11. A PHILOSOPHY OF ATTACK 146 Dedication: THIS BOOK IS FOR PATSY, WHOSE PATIENCE DURING THE YEARS I WAS DEVELOPING THE WILD BUNCH WAS MATCHED ONLY BY HER GOOD HUMOR. Copyright © 2006 Edmond E. Seay III - 2 - INTRODUCTION The Wild Bunch celebrates its sixth birthday in 2006. This revised playbook reflects the lessons learned during that period by Wild Bunch coaches on three continents operating at every level from coaching 8-year-olds to semi-professionals. The biggest change so far in the offense has been the addition in 2004 of the Rocket Sweep series (pp. 62-72). A public high school in Chicago and a semi-pro team in New Jersey both reached their championship game using the new Rocket-fueled Wild Bunch. A youth team in Utah won its state championship running the offense practically verbatim from the playbook. A number of coaches have requested video resources on the Wild Bunch, and I am happy to say a DVD project is taking shape which will feature not only game footage but extensive whiteboard analysis of the offense, as well as information on its installation.