017-030 Sugiyama(責)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Beautiful in Books TO

THE WORLD BEAUTIFUL IN BOOKS BY LILIAN WHITING Author of " The World Beautiful," in three volumes, First, Second, " " and Third Series ; After Her Death," From Dreamland Sent," " Kate Field, a Record," " Study of Elizabeth Barrett Browning," etc. If the crowns of the world were laid at my feet in exchange for my love of reading, 1 would spurn them all. — F^nblon BOSTON LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY ^901 PL Copyright, 1901, By Little, Brown, and Company. All rights reserved. I\17^ I S ^ November, 1901 UNIVERSITY PRESS JOHN WILSON AND SON • CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A. Lilian SMIjttins'fii glMoriiB The World Beautiful. First Series The World Beautiful. Second Series The World Beautiful. Third Series After her Death. The Story of a Summer From Dreamland Sent, and Other Poems A Studv of Elizabeth Barrett Browning The Spiritual Significance Kate Field: a Record The World Beautiful in Books TO One whose eye may fall upon these pages; whose presence in tlie world of thought and achievement enriches life ; whose genius and greatness of spirit inspire my every day with renewed energy and faith, — this quest for " The World Beautiful" in literature is inscribed by LILIAN WHITING. " The consecration and the poeVs dream" CONTENTS. BOOK I. p,,. As Food for Life 13 BOOK II. Opening Golden Doors 79 BOOK III. The Rose of Morning 137 BOOK IV. The Chariot of the Soul 227 BOOK V. The Witness of the Dawn 289 INDEX 395 ; TO THE READER. " Great the Master And sweet the Magic Moving to melody- Floated the Gleam." |0 the writer whose work has been en- riched by selection and quotation from " the best that is known and thought in* the world," it is a special pleasure to return the grateful acknowledgments due to the publishers of the choice literature over whose Elysian fields he has ranged. -

Sonoma County's Nineteenth Century Utopian Colonies

SHADOWS ON THE LAND: SONOMA COUNTY'S NINETEENTH CENTURY UTOPIAN COLONIES by Varene Anderson A thesis submitted to Sonoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Date Copyright 1992 By Varene Anderson ii AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER'S THESIS Permission to reproduce this thesis in its entirety must be obtained from me. Permission to reproduce parts of this thesis must be obtained from me. DATE: ~A 1,/99:2 I Signature City, State, Zip iii SHADOWS ON THE LAND: SONOMA COUNTY i S NINETEENTH CENTURY UTOPIAN COLONIES A thesis by Varene Anderson ABSTRACT purpose of the Study: Between 1875 and 1900, Sonoma county was the site of four utopian colonies, Fountaingrove, Preston, Icaria Speranza and Altruria. These colonies had religious and social reform origins, an agricultural economic base, and a message to present to the world. The purpose of this study is to examine generally the architecture, use of space and land, and community relationships of these colonies to determine if they builtin contemporary styles, used spatial arrangement to facilitate their communal lifestyle, were good stewards of the land, and perceived as good neighbors by nearby communities. This is intended as an overview of the four colonies to determine how they fit into Sonoma county culturally. Procedure: To determine how these colonies used architecture, space and land, and ,fit into their community, books, newspapers, and personal memOl.rs were consulted. In addition, personal interviews and inspection of the sites were conducted where possible. conclusions: The four Nineteenth century Sonoma county utopian colonies did not stand out architecturally from neighboring farms. -

Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit Futures in Dave Hutchinson’S Fractured Europe Quartet

humanities Article Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit Futures in Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe Quartet Hadas Elber-Aviram Department of English, The University of Notre Dame (USA) in England, London SW1Y 4HG, UK; [email protected] Abstract: Recent years have witnessed the emergence of a new strand of British fiction that grapples with the causes and consequences of the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union. Building on Kristian Shaw’s pioneering work in this new literary field, this article shifts the focus from literary fiction to science fiction. It analyzes Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe quartet— comprised of Europe in Autumn (pub. 2014), Europe at Midnight (pub. 2015), Europe in Winter (pub. 2016) and Europe at Dawn (pub. 2018)—as a case study in British science fiction’s response to the recent nationalistic turn in the UK. This article draws on a bespoke interview with Hutchinson and frames its discussion within a range of theories and studies, especially the European hermeneutics of Hans-Georg Gadamer. It argues that the Fractured Europe quartet deploys science fiction topoi to interrogate and criticize the recent rise of English nationalism. It further contends that the Fractured Europe books respond to this nationalistic turn by setting forth an estranged vision of Europe and offering alternative modalities of European identity through the mediation of photography and the redemptive possibilities of cooking. Keywords: speculative fiction; science fiction; utopia; post-utopia; dystopia; Brexit; England; Europe; Dave Hutchinson; Fractured Europe quartet Citation: Elber-Aviram, Hadas. 2021. Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit 1. Introduction Futures in Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe Quartet. -

Stae

GEORGE C. CARRINGTON, JR. STAe <ffnwnetibe The World and Art of the Howells Novel Ohio State University Press $6.25 THE IMMENSE COMPLEX DRAMA The World and Art of the Howells Novel GEORGE C. CARRINGTON, JR. One of the most productive and complex of the major American writers, William Dean Howells presents many aspects to his biogra phers and critics — novelist, playwright, liter ary critic, editor, literary businessman, and Christian Socialist. Mr. Carrington chooses Howells the novelist as the subject of this penetrating examination of the complex relationships of theme, subject, technique, and form in the world of Howells fiction. He attempts to answer such questions as, What happens if we look at the novels of Howells with the irreducible minimum of exter nal reference and examine them for meaning? What do their structures tell us? What are their characteristic elements? Is there significance in the use of these elements? In the frequency of their use? In the patterns of their use? Avoiding the scholar-critic's preoccupation with programmatic realism, cultural concerns, historical phenomena, and parallels and influ ences, Mr. Carrington moves from the world of technical criticism into Howells' fiction and beyond, into the modern world of anxious, struggling, middle-class man. As a result, a new Howells emerges — a Howells who interests us not just because he was a novelist, but because of the novels he wrote: a Howells who lives as an artist or not at all. George C. Carrington, Jr., is assistant pro fessor of English at the Case Institute of Tech nology in Cleveland, Ohio. -

William Dean Howells and the Antiurban Tradition 55

william dean howells and the antiurban tradition a reconsideration gregory I. crider The debate about William Dean Howells' attitudes toward the late nineteenth-century American city involve the much broader question of the place of antiurbanism in American thought. Responding to the charges of H. L. Mencken, Sinclair Lewis and other post-World War I critics who had condemned the author as a complacent symbol of the nineteenth-century literary establishment, scholars in the fifties and early sixties portrayed him as a Middle Western rural democrat who spent much of his adult life criticizing urban-industrial America.1 Unfortu nately, in attempting to revive Howells' reputation, these critics exag gerated his occasional nostalgia for the Ohio village of his youth, leaving the impression that he was an alienated critic of the city, if not genuinely antiurban. Although recent scholars have partly revised this view, critics have generally continued to accept the argument that the author's well- known affinity for socialism, together with his nostalgia for a vanishing countryside, left him an unswerving critic of the city.2 During the years in which scholars were discovering these antiurban sentiments, urban historians and sociologists began challenging the depth and cohesiveness of what had long been accepted as a monolithic, anti- urban tradition, dating back to Jefferson and Crevecoeur, and persisting through the transcendentalists, the pragmatists and literary naturalists, and the Chicago school of urban sociology, to the present. R. -

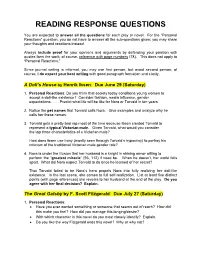

Reading Response Questions

READING RESPONSE QUESTIONS You are expected to answer all the questions for each play or novel. For the “Personal Reactions” question, you do not have to answer all the sub-questions given; you may share your thoughts and reactions instead. Always include proof for your opinions and arguments by defending your position with quotes form the work; of course, reference with page numbers (78). This does not apply to “Personal Reactions.” Since journal writing is informal, you may use first person, but avoid second person; of course, I do expect your best writing with good paragraph formation and clarity. A Doll’s House by Henrik IBsen: Due June 29 (Saturday) 1. Personal Reactions: Do you think that society today conditions young women to accept a doll-like existence? Consider fashion, media influence, gender expectations . Predict what life will be like for Nora or Torvald in ten years. 2. Notice the pet names that Torvald calls Nora. Give examples and analyze why he calls her these names. 3. Torvald gets a pretty bad rap most of the time because Ibsen created Torvald to represent a typical Victorian male. Given Torvald, what would you consider the top three characteristics of a Victorian male? How does Ibsen use irony (mostly seen through Torvald’s hypocrisy) to portray his criticism of the traditional Victorian male gender role? 4. Nora is under the illusion that her husband is a knight in shining armor willing to perform the “greatest miracle” (93, 112) if need be. When he doesn’t, her world falls apart. What did Nora expect Torvald to do once he learned of her secret? That Torvald failed to be Nora’s hero propels Nora into fully realizing her doll-like existence. -

The Utopia MEGAPACK™ Is Copyright © 2014 by Wildside Press, LLC

Contents COPYRIGHT INFO . 3 A NOTE FROM THE PUBLISHER . 4 . The MEGAPACK™ Ebook Series . 6. EREWHON, by Samuel Butler [Part 1] . 14 EREWHON, by Samuel Butler [Part 2] . 107 MOVING THE MOUNTAIN, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman . 227. HERLAND, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman . 367 EQUALITY, by Edward Bellamy [Part 1] . 518 EQUALITY, by Edward Bellamy [Part 2] . 636 CAESAR’S COLUMN, by Ignatius Donnelly [Part 1] . 937 . CAESAR’S COLUMN, by Ignatius Donnelly [Part 2] . .1034 . CAESAR’S COLUMN, by IgnatiusSample Donnelly file [Part 3] . .1135 . THE REPUBLIC OF THE FUTURE, by Anna Bowman Dodd . 1205. A CRYSTAL AGE, by W . H . Hudson [Part 1] . 1234 A CRYSTAL AGE, by W . H . Hudson [Part 2] . 1314 A TRAVELER FROM ALTRURIA, by W . D . Howells . 1387 FREELAND: A SOCIAL ANTICIPATION, by Dr . Theodor Hertzka [Part 1] . 1560 FREELAND: A SOCIAL ANTICIPATION, by Dr . Theodor Hertzka [Part 2] . 1691 FREELAND: A SOCIAL ANTICIPATION, by Dr . Theodor Hertzka Contents | 1 [Part 3] . 1812 FREELAND: A SOCIAL ANTICIPATION, by Dr . Theodor Hertzka [Part 4] . 1941 MIZORA: A PROPHECY, by Mary E . Bradley Lane . 2076 SOLARIS FARM, by Milan C . Edson [Part 1] . 2227 . SOLARIS FARM, by Milan C . Edson [Part 2] . 2337 . SOLARIS FARM, by Milan C . Edson [Part 3] . 2451 . LOOKING BACKWARD, by Edward Bellamy [Part 1] . 2777 . LOOKING BACKWARD, by Edward Bellamy [Part 2] . 2881 . SOME PICTURES OF A SOCIALIST FUTURE, by Eugene Richter . 2980 UTOPIA, by Thomas More . 2994 . THE COMMONWEALTH OF OCEANA, by James Harrington [Part 1] . 3097 THE COMMONWEALTH OF OCEANA, by James Harrington [Part 2] . 3202 THE COMMONWEALTH OF OCEANA, by James Harrington [Part 3] . -

Andover-1913.Pdf (7.550Mb)

TOWN OF ANDOVER ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Receipts and Expenditures ««II1IUUUI«SV FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING JANUARY 13, 1913 ANDOVER, MASS. THE ANDOVER PRESS *9 J 3 CONTENTS Almshouse Expenses, 7i Memorial Day, 58 Personal Property at, 7i Memorial Hall Trustees' Relief of, out 74 Report, 57, 121 Repairs on, 7i Miscellaneous, 66 Superintendent's Report, 75 Moth Suppression, 64 Animal Inspector, 86 Notes Given, Appropriations, 1912, 17 58 Art Gallery, 146 Notes Paid, 59 Assessors' Report 76 Overseers of Poor, 69 Assets, 93 Park Commissioner, 56 Auditor's Report, 105 Park Commissioners' Report 81 Board of Health, 65 Playstead, 55 Board of Public Works, Appen dix, Police, 53, 79 Sewer Maintenance, 63 Sewer Sinking Funds, 63 Printing and Stationery, 55 Water Maintenance, 62 Punchard Free School, Report Water Construction, 63 of Trustees, 101 Water Sinking Funds, 63 Repairs on old B. V. School, 68 Bonds, Redemption of, 62 Schedule of Town Property, 82 Collector's Account, 89 Schoolhouses, 29 Cornell Fund, 88 Schools, 23 County Tax, 56 School Books and Supplies, 3i Daughters of Revolution 68 Dog Tax 56 Selectmen's Report, 23 Dump, care of 58 Sidewalks, 42 Earnings Town Horses, 48 Soldiers' Relief, 74 Elm Square Improvements, 43 Snow, Removal of, 43 Fire Department, 51 77 Spring Grove Cemetery, 57, 87 Haggett's Pond Land, 68 State Aid, 74 Hay Scales, 58 State Tax, 55 Highways and Bridges, 33 Street Lighting, 50 Highway Surveyor, 46 Street List, 109 Horses and Drivers, 4i Town House, 54 Insurance, 63 Town Meeting, 7 Interest on Notes and Funds, 59 Town Officers, Liabilities, ior 4, 49 Town Warrant, 117 Librarian's Report, 125 Account, Macadam, 35 Treasurer's 93 Andover Street, 37 Tree Warden, 50 Salem Street, 39 Report, 85 TOWN OFFICERS, 1912 Selectmen, Assessors and Overseers of the Poor HARRY M. -

Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy

A Dissertation entitled “Keep Your Dirty Lights On:” Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy Exceptionalism in American Society by Daniel A. French Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in History _________________________________________ Dr. Diane F. Britton, Committee Chairperson _________________________________________ Dr. Peter Linebaugh, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Daryl Moorhead, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Kim E. Nielsen, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Patricia Komuniecki Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2014 Copyright 2014, Daniel A. French This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the express permission of the author. An Abstract of “Keep Your Dirty Lights On:” Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy Exceptionalism in American Society by Daniel A. French Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in History The University of Toledo December 2014 Electricity has been defined by American society as a modern and clean form of energy since it came into practical use at the end of the nineteenth century, yet no comprehensive study exists which examines the roots of these definitions. This dissertation considers the social meanings of electricity as an energy technology that became adopted between the mid- nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth centuries. Arguing that both technical and cultural factors played a role, this study shows how electricity became an abstracted form of energy in the minds of Americans. As technological advancements allowed for an increasing physical distance between power generation and power consumption, the commodity of electricity became consciously detached from the steam and coal that produced it. -

Sex Roles, Utopia and Change. 33

sex roles, utopia and change. the family in late nineteenth-century Utopian literature kenneth m. roemer I In a late nineteenth-century Utopian novel Fillmore Flagg, founder of an idealistic farm community, falls in love with Fern Fenwich, at attractive heiress. She finances his community, and in a "Twentieth Cen tury Love Letter" he expresses his appreciation and affection: "My Darling Fern: Noblest, purest and most beautiful of women!" Her "Reply" is more excessive in its praise: "Ah, my chosen one! So manly; so noble, so true! . my hero . gallant Knight of Most Excellent Agri culture." Fern completes the image by crowning her future husband with a shining helmet adorned with corn tassel plumes.1 Today, readers would mock these love letters as examples of the sentimental mush that pervaded nineteenth-century popular literature. Indeed even late nineteenth-century literary critics and the defenders of the status quo chastised the authors of Utopian works for sugarcoating radical ideas with love stories and glimpses of marital bliss. To some extent, as Edward Bellamy admitted, this criticism was valid.2 But the descriptions of present and future love affairs and family life found in the flood of Utopian novels and tracts produced between 1888 (the pub lication date of Bellamy's immensely popular Looking Backward) and 1900 do, nevertheless, provide revealing insights into American attitudes about sex roles, and, furthermore, illuminate the complex mixture of "radicalism" and "conservatism" that characterizes many American re form movements. No claims can be made for the completeness of the sample upon which this survey is based. -

The Unique Cultural & Innnovative Twelfty 1820

Chekhov reading The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre Group, Stanislavski, Olga Knipper THE UNIQUE CULTURAL & INNNOVATIVE TWELFTY 1820-1939, by JACQUES CORY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Page INSPIRATION 5 INTRODUCTION 6 THE METHODOLOGY OF THE BOOK 8 CULTURE IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES IN THE “CENTURY”/TWELFTY 1820-1939 14 LITERATURE 16 NOBEL PRIZES IN LITERATURE 16 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN 1820-1939, WITH COMMENTS AND LISTS OF BOOKS 37 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN TWELFTY 1820-1939 39 THE 3 MOST SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN 39 THE 3 MORE SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – SPANISH, RUSSIAN, ITALIAN 46 THE 10 SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – PORTUGUESE, BRAZILIAN, DUTCH, CZECH, GREEK, POLISH, SWEDISH, NORWEGIAN, DANISH, FINNISH 50 12 OTHER EUROPEAN LITERATURES – ROMANIAN, TURKISH, HUNGARIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, UKRAINIAN (20 EACH), AND IRISH GAELIC, BULGARIAN, ALBANIAN, ARMENIAN, GEORGIAN, LITHUANIAN (10 EACH) 56 TOTAL OF NOS. OF AUTHORS IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES BY CLUSTERS 59 JEWISH LANGUAGES LITERATURES 60 LITERATURES IN NON-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES 74 CORY'S LIST OF THE BEST BOOKS IN LITERATURE IN 1860-1899 78 3 SURVEY ON THE MOST/MORE/SIGNIFICANT LITERATURE/ART/MUSIC IN THE ROMANTICISM/REALISM/MODERNISM ERAS 113 ROMANTICISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 113 Analysis of the Results of the Romantic Era 125 REALISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 128 Analysis of the Results of the Realism/Naturalism Era 150 MODERNISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 153 Analysis of the Results of the Modernism Era 168 Analysis of the Results of the Total Period of 1820-1939 -

“The Spectre of Uncertainty”: Chance in Bellamy's Utopian Fictions

“The Spectre of Uncertainty”: Chance in Bellamy’s Utopian Fictions Thomas Dikant ABSTRACT Edward Bellamy’s utopian novels Looking Backward (1888) and Equality (1897) imagine a new society of equality, justice, and a life of plenty, where no one has to fear for the security and wellbeing of their own or future generations. In Bellamy’s utopian future, the “spectre of Uncer- tainty,” which had been a permanent threat to the lives of people in the late nineteenth century, is presented as having disappeared. And yet, for all of its emphasis on security, Bellamy’s uto- pian vision in fact does not exclude chance, risk, or accident. Placing statistics at the center of his utopian economy, Bellamy imagines a society that is based on probability rather than certainty. Bellamy’s industrial workforce of the utopian future is modeled on the ideal of the army, which he envisions as both a rational organization and an organization predicated on risk. Meanwhile, the possibility of accident not only plays a considerable role in the smooth workings of the uto- pian system but is also the very precondition for the transportation of the novel’s protagonist, Julian West, into the future of the year 2000. Thus, in both Looking Backward and Equality, the unpredictable event, the error, and the accident have to be possible for utopia to exist. I. Uncertain Conditions In Edward Bellamy’s 1888 Utopian novel Looking Backward 2000-1887, “[a] spectre is haunting” late nineteenth-century Boston, but it is not—Marx and En- gels notwithstanding—“the spectre of Communism” (Marx and Engels 218).1 At the end of the novel, Julian West, the first-person narrator, finds himself one night caught in a dream.