Birdsof Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brazil: the Pantanal and Amazon, July 2015

Tropical Birding Trip Report Brazil: The Pantanal and Amazon, July 2015 BRAZIL: The Pantanal and Amazon 1-15 July 2015 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos, except for the Blue Finch, by Nick Athanas. Thanks to Mark Gawn for sharing his Blue Finch photo Bare-eyed Antbird was one of many highlights from this fun trip From the unparalleled biodiversity of the primeval Amazonian forest to the amazing abundance of wildlife in the Pantanal, this tour is always fascinating and great fun, and the superb lodges and tasty food make it especially enjoyable. This year was wetter than normal and we even got soaked once in the Pantanal, which is almost unheard of in July; the extra water definitely helped the overall bird numbers, so I certainly was not complaining, and it was still pretty darn dry compared to most South American tours. When I asked the group at the end of the trip for favorite sightings, everyone mentioned something totally different. There were so many memorable sightings that trying to pick one, or even a few, was almost futile. Some that were mentioned, in no real order, included: superb close-ups of Bare-eyed Antbirds at an antswarm at Cristalino (photo above); the “ginormous” Yellow Anaconda we saw crossing the Transpantanal Highway on our last full day, the minute and fabulous Horned Sungem from the Chapada, a superb encounter with the rare White-browed Hawk from one of the towers at Cristalino, our very successful hunt for the newly-described Alta Floresta Antpitta, and last but far from least, the magnificent Jaguar we saw for an extended period of time along the banks of the Três Irmãos River. -

Guia Para Observação Das Aves Do Parque Nacional De Brasília

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234145690 Guia para observação das aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília Book · January 2011 CITATIONS READS 0 629 4 authors, including: Mieko Kanegae Fernando Lima Favaro Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Bi… 7 PUBLICATIONS 74 CITATIONS 17 PUBLICATIONS 69 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Fernando Lima Favaro on 28 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Brasília - 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA Aílton C. de Oliveira Mieko Ferreira Kanegae Marina Faria do Amaral Fernando de Lima Favaro Fotografia de Aves Marcelo Pontes Monteiro Nélio dos Santos Paulo André Lima Borges Brasília, 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO APRESENTAÇÃO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA É com grande satisfação que apresento o Guia para Observação REPÚblica FEDERATiva DO BRASIL das Aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília, o qual representa um importante instrumento auxiliar para os observadores de aves que frequentam ou que Presidente frequentarão o Parque, para fins de lazer (birdwatching), pesquisas científicas, Dilma Roussef treinamentos ou em atividades de educação ambiental. Este é mais um resultado do trabalho do Centro Nacional de Pesquisa e Vice-Presidente Conservação de Aves Silvestres - CEMAVE, unidade descentralizada do Instituto Michel Temer Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) e vinculada à Diretoria de Conservação da Biodiversidade. O Centro tem como missão Ministério do Meio Ambiente - MMA subsidiar a conservação das aves brasileiras e dos ambientes dos quais elas Izabella Mônica Vieira Teixeira dependem. -

Northeast Brazil

Northeast Brazil 10th December 2017 – 10th January 2018 Sjoerd Radstaak [email protected] Introduction This trip report describes a four-week-trip to Northeast-Brazil, together with good friends Pieter van Veelen, Jelmer Poelstra and Lars Buckx. For three of us, it was our first time of proper birding in South-America. Only Jelmer had been in Ecuador, Peru and Colombia before, but never in this part of the continent. Sjoerd did visit NE Brazil in December 2018 again as a tour leader for BirdingBreaks.nl. Based on the high degree of endemism, combined with the fact many of these endemics are critically endangered, we decided to visit NE-Brazil. Also, it appears to be a good destination to become familiar with the bird families of South-America without getting overwhelmed by the number of species. While Brazil has always been a birder’s destination, the north-eastern part of the country has long been the forgotten corner of Brazil. However, more than 15 birds new to science have been described here over the last 20 years. Of those, the most famous is - of course - Araripe Manakin: only discovered in 1996 and first described in 1998. Even today avian (re)discoveries are ‘regular’ here, for example the discovery of Blue-eyed ground-Dove in 2016 – a species that was believed to be extinct, as it had last been seen in 1941! Others include Alagoas Foliage-Gleaner, Orange-bellied Antwren and Pinto’s Spinetail. Sadly enough, many of these newly described species and others are now critically endangered or even extinct – with Alagoas Foliage-Gleaner last seen in 2012. -

The Birds of Serra Da Canastra National Park and Adjacent Areas, Minas Gerais, Brazil

COT/NGA 10 The birds of Serra da Canastra National Park and adjacent areas, Minas Gerais, Brazil Lufs Fabio Silveira E apresentada uma listagem da avifauna do Parque Nacional da Serra da Canastra e regi6es pr6ximas, e complementada corn observac;:6es realizadas por outros autores. Sao relatadas algumas observac;:6es sobre especies ameac;:adas ou pouco conhecidas, bem como a extensao de distribuic;:ao para outras. Introduction corded with photographs or tape-recordings, using Located in the south-west part of Minas Gerais a Sony TCM 5000EV and Sennheiser ME 66 direc state, south-east Brazil, Serra da Canastra Na tional microphone. Tape-recordings are deposited 8 9 tional Park (SCNP, 71,525 ha , 20°15'S 46°37'W) is at Arquivo Sonora Elias Pacheco Coelho, in the regularly visited by birders as it is a well-known Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil area in which to see cerrado specialities and a site (ASEC). for Brazilian Merganser Mergus octosetaceus. How A problem with many avifaunal lists concerns ever, Forrester's6 checklist constitutes the only the evidence of a species' presence in a given area. major compilation ofrecords from the area. Here, I Many species are similar in plumage and list the species recorded at Serra da Canastra Na vocalisations, resulting in identification errors and tional Park and surrounding areas (Appendix 1), making avifaunal lists the subject of some criti 1 with details of threatened birds and range exten cism . Several ornithologists or experienced birders sions for some species. have presented such lists without specifying the evidence attached to each record-in many cases Material and methods it is unknown if a species was tape-recorded, or a The dominant vegetation of Serra da Canastra specimen or photograph taken. -

Tocantins and Pará Tour

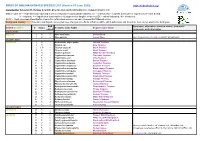

(Goiás, Tocantins, Pará) Day Location (state) Comments 1 Brasilia Arrival 2 Brasilia – São Domingos (370Km) AM Birding and transfer. 3 São Domingos – Taquaruçu (Palmas) (600Km) AM Birding and transfer. 4 Taquaruçu Full Day Birding. 5 Palmas – Lagoa da Confusão (240Km) AM Birding and transfer. 6 Lagoa da Confusão – Pium (200Km) AM Birding and transfer. 7 Pium (Canguçu Research Center) Full Day Birding. 8 Pium – Caseara (200Km) AM Birding and transfer. 9 Caseara – Miranorte (250Km) AM Birding and transfer. 10 Miranorte – 2 Irmãos – C. Magalhães (200Km) AM Birding and transfer. 11 Couto Magalhães – Carajás Nat. Forest (500Km) AM Birding and transfer. 12 Carajás National Forest Full Day Birding. 13 Carajás National Forest Full Day Birding. 14 Carajás National Forest Full Day Birding. 15 Carajás National Forest Departure. Suggested Period: From June to January. Brasilia (A), São Domingos (B), Taquaruçu (Palmas) (C) Porto Nacional e Miracema (D), Lagoa da Confusão (E), Canguçu Research Center (Pium) (F), Cantão State Park (Caseara) (G), Dois Irmãos (H), Couto Magalhães (I), Carajás National Forest (Parauapebas) (J). Day 1: Arrival in BRASILIA where we spend the night. Area description: is the capital of Brazil. The capital is located in the Center-West region of the country, along the geographic region known as Central Plateau (Planalto Central), with altitudes between 1,000 and 1,200 meters above sea level. The predominant vegetation in this region is the Cerrado. The climate of Brasilia is tropical with dry season, with average monthly temperatures higher than 18°C and rainfall around 1,540 mm (mm) annually, concentrated between October and April. -

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

A Cerrado Bird Community in the Northernmost Portion of Northeastern Brazil - Recommendations for Conservation

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 22(4), 347-362 ARTICLE December 2014 A Cerrado bird community in the northernmost portion of northeastern Brazil - recommendations for conservation Mauro Pichorim1,3, Marcelo da Silva2, Bruno Rodrigo de Albuquerque França2, Tonny Marques de Oliveira-Júnior1 and Marcelo Câmara Rodrigues1 1 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Departamento de Botânica, Ecologia e Zoologia, Campus Universitário, Lagoa Nova, CEP 59078- 900, Natal, RN, Brazil. 2 Universidade Potiguar, Escola da Saúde, Curso de Ciências Biológicas, Laureate International Universities, Av. Senador Salgado Filho, 1610, Lagoa Nova, CEP 59056-000, Natal, RN, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 27 April 2014. Accepted on 10 November 2014. ABSTRACT: TheCerrado is the largest savanna in South America and it is rich in fauna and flora and considered a biodiversity hotspot. Its contact with the surrounding Amazon, Atlantic Forest and Caatinga is irregular, forming large diffuse ecotones in some regions and disjointed patches in others. TheCerrado patches located in the Amazon are relatively studied, but little is known about those in the Atlantic Forest and Caatinga. This article presents information on the composition of a bird community in a savanna formation on the coast of the northernmost portion of northeast Brazil (5o23'25"S / 35o30'25"W). This site was visited 17 times between October 2006 and August 2013. The total richness was 87 species distributed into 32 families. The followingCerrado endemics were recorded: Charitospiza eucosma and Porphyrospiza caerulescens. Other species recorded associated mainly with the Cerrado biome were Heliactin bilophus, Cypsnagra hirundinacea and Coryphaspiza melanotis. Some vulnerable and near threatened species were also recorded for the first time in the northernmost portion of northeastern Brazil, with some of these more than 1,000 km from their previously known localities. -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Safari Brazil: The Pantanal & More 2019 Sep 21, 2019 to Oct 6, 2019 Marcelo Padua & Dan Lane For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. We experienced the amazing termitaria-covered landscape of Emas National Park, where participant Rick Thompson got this evocative image, including two Aplomado Falcons, and a Pampas Deer. Brazil is a big place, and it is home to a wide variety of biomes. Among its most famous are the Amazon and the Pantanal, both occupy huge areas and have their respective hydrologies to thank for their existence. In addition to these are drier regions that cut the humid Amazon from the humid Atlantic Forest, this is known as the “Dry Diagonal,” home to the grasslands we observed at Emas, the chapada de Cipo, and farther afield, the Chaco, Pampas, and Caatinga. We were able to dip our toes into several of these incredible features, beginning with the Pantanal, one of the world’s great wetlands, and home to a wide array of animals, fish, birds, and other organisms. In addition to daytime outings to enjoy the birdlife and see several of the habitats of the region (seasonally flooded grasslands, gallery forest, deciduous woodlands, and open country that does not flood), we were able to see a wide array of mammals during several nocturnal outings, culminating in such wonderful results as seeing multiple big cats (up to three Ocelots and a Jaguar on one night!), foxes, skunks, raccoons, Giant Anteaters, and others. To have such luck as this in the Americas is something special! Our bird list from the region included such memorable events as seeing an active Jabiru nest, arriving at our lodging at Aguape to a crowd of Hyacinth Macaws, as well as enjoying watching the antics of their cousins the Blue-and-yellow Macaws. -

Birds of British Honduras. Notes on Some of the Birds Resident in That

BIRDS OF BRITISH HONDURAS BY R. P. DEVAS, O.P., M.C. B ir d s o f British Honduras NOTES ON SOME OF THE BIRDS RESIDENT IN THAT PART OF CENTRAL AMERICA BY F a th e r RAYMUND DEVAS, O.P., M.C. Yuille’s Printerie Limited, 66 Marine Square, Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, B.W .I. C B 491 By the same Author VISITORS’ BOOK OF BIRDS TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO MUIR, MARSHALL & CO . Booksellers Marine Square, Port-of-Spain, Trinidad. CONTENTS Page Foreword (v) SEA BIRDS — Brown Pelican 1 Frigate Bird 1 Terns 3 Laughing Gull 4 Yellow-billed Tropic Bird 5 Boobies 6 BIRDS OF THE LAND — Hummingbirds 15 Swifts 17 Swallows 19 Flycatchers 23 Thrashers and Thrushes 29 Wren 31 Honeycreeper 31 Warblers 32 Troupials 33 Vireos 38 Tanagers 43 Finches 45 Woodpeckers 49 Wood-hewer 52 Shrike 52 Cotinga 52 Chatterers 54 Owls 56 CONTENTS — Cont’d. Nightjars, Nighthawks 57 Ani 58 Cuckoos 59 Trogons 59 Motmot 61 Jacamar 62 Puff Bird 63 Macaws 63 Parrots 64 Toucans 65 Vultures 66 Hawks 67 Magpie 69 Pigeons and Doves 70 Game Birds 71 River-birds, Ducks, Waders 73 INDEX 81 FOREWORD. The birds of British Honduras include many of the birds you may meet again in other parts of Central America. Among them, quite apart from the migrants, will be noticed some that are to be found north of Mexico, and others that are to be seen also south of the Panama Canal. And East? Yes, I am happy to say, British Honduras has a number of birds in common with the West Indies, though some of them, as we shall see, show considerable differences in habits and song and even appearance. -

Birds of the Chapada Diamantina, Bahia, Brazil

Birds of the Chapada Diamantina, Bahia, Brazil Ricardo Parrini, Marcos A. Raposo, José Fernando Pacheco, André M. P. Carvalhães, Tadeu A. Melo Júnior, Paulo Sérgio M. Fonseca and Jeremy Minns Cotinga 11 (1999): 86–95 A avifauna da Chapada Diamantina é, ainda, muito pouco conhecida. O presente estudo visou estabelecer um quadro representativo da distribuição das aves dessa região pelos diferentes ambientes aí presentes. Para isso, foram efetuadas várias excursões a campo, que abrangeram um total de 19 localidades, onde foram registradas, por observação ou coleta, 359 espécies. Além da sua importância para o conhecimento da biogeografia das aves do Neotrópico, esse trabalho demonstra a importância da conservação dos hábitats locais, que vêm sofrendo com a expansão das atividades humanas na região. Introduction The avifauna of the Chapada Diamantina is surprisingly little-known. No specific study of the area has been undertaken and the only information concerning its birds is scattered through general reference works, e.g. Meyer de Schauensee5, Sick18,19 and Ridgely & Tudor14,15, or in surveys of nearby areas, such as those by Pinto8 and Gonzaga et al.3. As the various biomes of this geographical formation have already been subject to changes through the actions of man, particularly in the forested areas, thorough studies of the local fauna are urgently required. In order to undertake an adequate survey of the main biomes of this region, namely campos rupestres (arid mountain scrub), caatingas (arid lowland scrub), cerrados, gallery forests, humid forests (sensu Rizzini16) and humid areas in general, we made a number of trips to various parts of the Chapada (see map). -

Pantanal and Interior Brazil

Hyacinth Macaw – the largest parrot in the world is always the most wanted on this tour! Easy to understand why… (Eduardo Patrial) PANTANAL AND INTERIOR BRAZIL 2 – 14/22 OCTOBER 2016 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL With some amazing news, the 2016 Pantanal and Interior was just a superb trip to Brazil before taking a year break in 2017. Two Birdquest life birds (Bald Parrot and Rock Tapaculo) and several write-ins to the list were part of the outstanding result which combined perfectly species quality and quantity. The news came in the main tour and mostly in the extension to the Amazon, respectively with a visit to an Atlantic Forest remnant at Cipó and the new stay at the fascinating Rio Azul Lodge, north of Alta Floresta. But as the tour name says, we still got the best from the Pantanal and the Cerrado (Brazilian savannah) from central Brazil. A total of 616 species of birds were recorded this time, plus 29 mammals. Simply memorable our time spent in Minas Gerais state visiting two fantastic mountain ranges, the Serra da Canastra and Serra do Cipó with their vast grasslands and rocky fields; and later in the huge Mato Grosso state where we visited the mighty 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Pantanal and Interior Brazil 2016 www.birdquest-tours.com Pantanal with its spectacular fauna, the scenic Chapada dos Guimarães and its fine Cerrado and gallery forests, and finally the very rich Amazon forest around Alta Floresta in northern Mato Grosso where we visited the lovely Rio Azul Lodge (this one actually in the extreme south of Pará state) and the famous Cristalino Lodge. -

Brazil – Pantanal Custom Tour

Brazil – Pantanal Custom tour 10th - 21st August, 2015 Tour leader: Charley Hesse Report by Charley Hesse. Photos by Charley Hesse, Jack Faller & Jerry Connolly. Our group at the geocentric centre of South America, Chapada dos Guimaraes (Jerry Connolly) The Pantanal of Brazil is one of South America’s natural wonders and one of the top places for wildlife viewing on the continent. In addition to many other interesting mammals such as Brazilian Tapir, Giant Otter, Marsh Deer, South American Coati, Capybara and several species of Primates, the Pantanal is now THE place to see the amazing Jaguar. One of the main goals of our trip was to see these incredible animals and we spent 2 days cruising the Rio Cuiaba and had 3 wonderful encounters. The Pantanal is also a bird-lover’s paradise and some of the highlights from our numerous boat rides, drives and walks, included: Greater Rhea, Jabiru, Maguari Stork, Bare-faced Currassow, Southern Screamer, Sunbittern, Sungrebe, Toco Toucan and Hyacinth Macaw. After the Pantanal we visited Chapada dos Guimaraes with spectacular scenery and some very different habitats, where we saw White-eared Puffbird, Swallow-tailed Hummingbird, Pale-crested Woodpecker, Coal-crested & Blue Finches. To finish the trip we visited the very southern edge of Amazonia and we were privileged to see the critically endangered and recently rediscovered Cone- billed Tanager along with oodles many other great birds, like Red-necked Aracari, Spotted Puffbird and Flame-crested Manakin. With 344 species of birds plus numerous mammals, reptiles and butterflies, it was an extremely productive and enjoyable trip in good company.