Wouldn't It Be Nice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

2017 CATALOGUE for Over Forty Years Omnibus Press Has Been Publishing the Stories That Matter from the Music World

2017 CATALOGUE For over forty years Omnibus Press has been publishing the stories that matter from the music world. Omnibus Press is the World’s/Europe’s largest specialist publisher devoted to music writing, with around thirty new titles a year, with a backlist of over two hundred and seventy titles currently in print and many more as digital downloads. Omnibus Press covers pop, rock, classical, metal, country, psyche, prog, electronic, dance, rap, jazz and many more genres, in a variety of formats. With books that tell stories through graphic art and photography, memoirs and biographies, Omnibus has constantly evolved its list to challenge what a music book can be and this year we are releasing our first talking books. Among Omnibus Press’ earliest acquisitions was Rock Family Trees, by acclaimed music archivist Pete Frame, three editions of which remain in print to this day and have been the basis of two BBC TV series. Over the following decades Omnibus published many best-selling, definitive biographies on some of rock’s greatest superstars. These include Morrissey & Marr: The Severed Alliance by Johnny Rogan, Dear Boy: The Life Of Keith Moon by Tony Fletcher, Uptight: The Velvet Underground Story by Victor Bockris, Catch A Fire: The Life of Bob Marley by Timothy White, Stevie Nicks - Visions, Dreams & Rumours by Zoë Howe, Without Frontiers The Life And Music Of Peter Gabriel by Daryl Easlea and Under The Ivy: The Life & Music of Kate Bush and George Harrison: Behind The Locked Door, both by Graeme Thomson, all of which are regularly cited by magazines and critics as being amongst the finest rock biographies ever published. -

How the Documentary Film Functions for Bob Dylan Fans Theodore G

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2007 Documenting Dylan: How the documentary film functions for Bob Dylan fans Theodore G. Petersen University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Petersen, Theodore G., "Documenting Dylan: How the documentary film functions for Bob Dylan fans" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2321 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Documenting Dylan: How the Documentary Film Functions for Bob Dylan Fans by Theodore G. Petersen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Marcy Chvasta, Ph.D. Janna Jones, Ph.D. Mark Neumann, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 27, 2007 Keywords: music, popular culture, celebrity, rock ‘n’ roll, identity © Copyright 2007, Theodore G. Petersen ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Janna Jones. Enduring a move and a new position, Janna still found time to provide insights and encouragements throughout my writing and research process. Her contribution to this project and my education is much appreciated and will continue to help me throughout my academic career. I would like to thank my thesis committee members, Dr. -

Diversification and Post-Regionalism in North American Hip-Hop Flow

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "#$%&'#(#)*+#,-!*-.!/,'+01%2#,-*3#'4!#-!5,&+6!74%&#)*-!8#908,9!:3,;! ! ! "#$%&'($!)*($+#,! ! ! ! )#-&,.'#$.!/0!1*2(3!4#2#&,35! 635*7(35!635//7!/0!1*2(3! 138(77!9$(:#,2(.;! 1/$.,#&7<!=*#>#3<!?&$&@&! A-,(7!BCBC! ! ! A!.5#2(2!2*>'(..#@!./!138(77!9$(:#,2(.;!($!-&,.(&7!0*70(77'#$.!/0!.5#!,#D*(,#'#$.2!/0!.5#!@#E,##! /0!)/3./,!/0!F5(7/2/-5;G!1*2(3!H5#/,;! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! I!"#$%&'($!)*($+#,<!BCBC! 7<'+&*)+! ! "#E($$($E!($!.5#!7&.#!JKLC2<!M/,.5!A'#,(3&$!5(-N5/-!'*2(3!E,#O!($./!&!@/'($&$.! 3*7.*,&7!0/,3#P!4#E(/$&7!23#$#2!>/&2.#@!.5#(,!/O$!1?2!Q,&--#,2R!O5/2#!($@(:(@*&7!'*2(3&7!2.;7#2! E,#O!($3,#&2($E7;!2/-5(2.(3&.#@!&$@!@(:#,2#P!S,/'!&--,/T('&.#7;!BCCC!/$O&,@<!&!:&,(#.;!/0! 0&3./,2!5&:#!'/:#@!5(-N5/-!'*2(3!($./!&$!#,&!/0!-/2.N,#E(/$&7(2'P!A,.(2.2!0,/'!@(2-&,&.#! E#/E,&-5(3!,#E(/$2!,/*.($#7;!3/77&>/,&.#!O(.5!/$#!&$/.5#,<!&$@!.5#!($.#,$#.U2!&>(7(.;!./!0&3(7(.&.#! :(,.*&7!'*2(3&7!3/''*$(.(#2!&$@!E#$,#2!5&2!&,E*&>7;!,#$@#,#@!.5#!(@#&!/0!7/3&7!2-&3#!($!5(-!5/-! 7#22!&$@!7#22!('-/,.&$.P!V$!.5(2!@(22#,.&.(/$!V!0(,2.!#T-7/,#!5/O!,5;.5'!&$@!'#.#,!($!07/O! Q,&--($ER!#:/7:#@!&$@!>#3&'#!'/,#!@(:#,2#!@*,($E!5(-!5/-U2!#&,7(#,!;#&,2!&2!&!,#E(/$&7!E#$,#<! &$@!V!.5#$!&22#22!O5#.5#,!,5;.5'!&$@!'#.#,!($!07/O!5&:#!>#3/'#!'/,#!5/'/E#$#/*2!@*,($E!.5(2! E#$,#U2!'/,#!,#3#$.<!-/2.N,#E(/$&7!#,&P!H/!&35(#:#!.5#2#!E/&72<!V!@#:#7/-#@!&$@!&$&7;W#@!.O/! 2/$E!3/,-/,&!@,&O$!0,/'!!"##$%&'()"%*''&E&W($#!&$@!.5#!8,&'';!AO&,@!3&.#E/,;!/0!"#2.!4&-! 6/$EP!V!'&$*&77;!.,&$23,(>#@!&$@!&$&7;W#@!XYB!:#,2#2!/0!07/O!0,/'!JZC!2/$E2<!0/3*2($E!/$! -

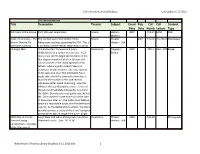

Web Historic Theatres Library Database 6-12-2016.Xlsx 1 STG Historical Library Database Last Update 6-12-2016

STG Historical Library Database Last Update 6-12-2016 STG Library Database Title Description Theater Subject Event Pub Call Call Content Date Date Numb Letters Type 100 Years at the Moore DVD 100 year celebration Moore History - 2007 792.09er MOO DVD Modern 100th Anniversary - The The contest was in the Seattle Times Moore Theater 2007 792.09 100 MOO Newspaper Moore Theatre My Newspaper and was sponsored by STG. This is History - USA Memories Contest a collection of the entries returned to STG on 12 Angry Men "12 Angry Men" focuses on a jury's Paramount Tragedy / 2007 792.1 AAA - FZZ Binder deliberations in a capital murder case. A 12- Drama man jury is sent to begin deliberations in the first-degree murder trial of an 18-year-old Latino accused in the stabbing death of his father - where a guilty verdict means an automatic death sentence. The case appears to be open-and-shut: The defendant has a weak alibi; a knife he claimed to have lost is found at the murder scene; and several witnesses either heard screaming - saw the killing or the boy fleeing the scene. Eleven of the jurors immediately vote guilty; only Juror No. 8 (Mr. Davis) casts a not guilty vote. At first Mr. Davis' bases his vote more so for the sake of discussion after all - the jurors must believe beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant is guilty. As the deliberations unfold - the story quickly becomes a study of the jurors' complex personalities (which range from wise - bright 1928 Shot of Seattle Large black and white photograph printed on Paramount Theater 1928 792.09 Photograph Theatre During stretched canvas. -

A Corpus Analysis of Rock Harmony

Popular Music (2011) Volume 30/1. Copyright © Cambridge University Press 2011, pp. 47–70 doi:10.1017/S026114301000067X A corpus analysis of rock harmony TREVOR DE CLERCQ and DAVID TEMPERLEY Eastman School of Music, Department of Music Theory, 26 Gibbs Street, Rochester, NY 14604, USA E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this study, we report a corpus analysis of rock harmony. As a corpus, we used Rolling Stone magazine’s list of the ‘500 Greatest Songs of All Time’; we took the 20 top-ranked songs from each decade (the 1950s through the 1990s), creating a set of 100 songs. Both authors analysed all 100 songs by hand, using conventional Roman numeral symbols. Agreement between the two sets of analyses was over 90 per cent. The analyses were encoded using a recursive notation, similar to a context-free grammar, allowing repeating sections to be encoded succinctly. The aggregate data was then subjected to a variety of statistical analyses. We examined the frequency of different chords and chord transitions. The results showed that IV is the most common chord after I and is especially common preceding the tonic. Other results concern the frequency of different root motions, patterns of co-occurrence between chords, and changes in harmonic practice across time. Introduction In the extensive scholarship on rock that has emerged over the last two decades, har- mony has been a central concern. Many analytical studies of individual songs have focused primarily or even exclusively on harmony and other aspects of pitch organ- isation (see for example many of the essays in Covach & Boone 1997, Holm-Hudson 2002 and Everett 2008a). -

The Development of the Beach Boys' Sound

When I Grow Up: The Development of the Beach Boys’ Sound (1962-1966) Author O'Regan, Jade Simone Published 2014 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Queensland Conservatorium DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2556 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367243 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au When I Grow Up: The Development of the Beach Boys’ Sound (1962-1966) Volume One Jade Simone O’Regan B.PopMus (Hons) Queensland Conservatorium of Music Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December, 2013 2 Abstract The Beach Boys are an American rock group whose career has spanned over fifty years. However, it was between 1962 and 1966 that the group had most of their chart success and that their unique ‘sound’ was crystallised. This study takes a broad, big- picture overview of the Beach Boy’s repertoire from this period and charts the development of their sound through the apprentice-craft-art (ACA) framework. The concept of a ‘sound’ is able to draw together the musical, technological, sociological and historical elements that, when combined, create the sound of the Beach Boys during the 1962-1966 period. The flexibility of this concept means that areas often overlooked in popular music studies and in studies on the Beach Boys in general (particularly the roles of production and instrument types), are able to be woven into analyses of more traditional musical elements (such as song structure or chord progressions). -

Jeff Wragg Phd Thesis

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. The High Art of Trip Hop: Extending the Bristol Sound by Incorporating Compositional Approaches from Classical Music A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music at The University of Waikato by Jeffrey Wragg 2018 ii Abstract ‘The High Art of Trip Hop’ defines the Bristol sound and extends it through new composition techniques. The two-part thesis combines musicological and practice-led research. Part one analyses the Bristol sound, a style of popular music that developed in Bristol, England during the 1990s and is also known as ‘trip hop’. It offers an historical overview of the style’s evolution, and identifies the principal composition, performance, and production traits. Part two is a portfolio of seven original songs that demonstrate ways of extending the style by incorporating compositional approaches from classical music.