Tropical Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ast 443 / Phy 517

AST 443 / PHY 517 Astronomical Observing Techniques Prof. F.M. Walter I. The Basics The 3 basic measurements: • WHERE something is • WHEN something happened • HOW BRIGHT something is Since this is science, let’s be quantitative! Where • Positions: – 2-dimensional projections on celestial sphere (q,f) • q,f are angular measures: radians, or degrees, minutes, arcsec – 3-dimensional position in space (x,y,z) or (q, f, r). • (x,y,z) are linear positions within a right-handed rectilinear coordinate system. • R is a distance (spherical coordinates) • Galactic positions are sometimes presented in cylindrical coordinates, of galactocentric radius, height above the galactic plane, and azimuth. Angles There are • 360 degrees (o) in a circle • 60 minutes of arc (‘) in a degree (arcmin) • 60 seconds of arc (“) in an arcmin There are • 24 hours (h) along the equator • 60 minutes of time (m) per hour • 60 seconds of time (s) per minute • 1 second of time = 15”/cos(latitude) Coordinate Systems "What good are Mercator's North Poles and Equators Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?" So the Bellman would cry, and the crew would reply "They are merely conventional signs" L. Carroll -- The Hunting of the Snark • Equatorial (celestial): based on terrestrial longitude & latitude • Ecliptic: based on the Earth’s orbit • Altitude-Azimuth (alt-az): local • Galactic: based on MilKy Way • Supergalactic: based on supergalactic plane Reference points Celestial coordinates (Right Ascension α, Declination δ) • δ = 0: projection oF terrestrial equator • (α, δ) = (0,0): -

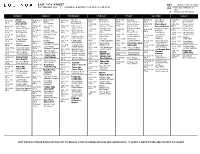

E a S T 7 4 T H S T R E E T August 2021 Schedule

E A S T 7 4 T H S T R E E T KEY St udi o key on bac k SEPT EM BER 2021 SC H ED U LE EF F EC T IVE 09.01.21–09.30.21 Bolld New Class, Instructor, or Time ♦ Advance sign-up required M O NDA Y T UE S DA Y W E DNE S DA Y T HURS DA Y F RII DA Y S A T URDA Y S UNDA Y Atthllettiic Master of One Athletic 6:30–7:15 METCON3 6:15–7:00 Stacked! 8:00–8:45 Cycle Beats 8:30–9:30 Vinyasa Yoga 6:15–7:00 6:30–7:15 6:15–7:00 Condiittiioniing Gerard Conditioning MS ♦ Kevin Scott MS ♦ Steve Mitchell CS ♦ Mike Harris YS ♦ Esco Wilson MS ♦ MS ♦ MS ♦ Stteve Miittchellll Thelemaque Boyd Melson 7:00–7:45 Cycle Power 7:00–7:45 Pilates Fusion 8:30–9:15 Piillattes Remiix 9:00–9:45 Cardio Sculpt 6:30–7:15 Cycle Beats 7:00–7:45 Cycle Power 6:30–7:15 Cycle Power CS ♦ Candace Peterson YS ♦ Mia Wenger YS ♦ Sammiie Denham MS ♦ Cindya Davis CS ♦ Serena DiLiberto CS ♦ Shweky CS ♦ Jason Strong 7:15–8:15 Vinyasa Yoga 7:45–8:30 Firestarter + Best Firestarter + Best 9:30–10:15 Cycle Power 7:15–8:05 Athletic Yoga Off The Barre Josh Mathew- Abs Ever 9:00–9:45 CS ♦ Jason Strong 7:00–8:00 Vinyasa Yoga 7:00–7:45 YS ♦ MS ♦ MS ♦ Abs Ever YS ♦ Elitza Ivanova YS ♦ Margaret Schwarz YS ♦ Sarah Marchetti Meier Shane Blouin Luke Bernier 10:15–11:00 Off The Barre Gleim 8:00–8:45 Cycle Beats 7:30–8:15 Precision Run® 7:30–8:15 Precision Run® 8:45–9:45 Vinyasa Yoga Cycle Power YS ♦ Cindya Davis Gerard 7:15–8:00 Precision Run® TR ♦ Kevin Scott YS ♦ Colleen Murphy 9:15–10:00 CS ♦ Nikki Bucks TR ♦ CS ♦ Candace 10:30–11:15 Atletica Thelemaque TR ♦ Chaz Jackson Peterson 8:45–9:30 Pilates Fusion 8:00–8:45 -

Ephemeris Time, D. H. Sadler, Occasional

EPHEMERIS TIME D. H. Sadler 1. Introduction. – At the eighth General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union, held in Rome in 1952 September, the following resolution was adopted: “It is recommended that, in all cases where the mean solar second is unsatisfactory as a unit of time by reason of its variability, the unit adopted should be the sidereal year at 1900.0; that the time reckoned in these units be designated “Ephemeris Time”; that the change of mean solar time to ephemeris time be accomplished by the following correction: ΔT = +24°.349 + 72s.318T + 29s.950T2 +1.82144 · B where T is reckoned in Julian centuries from 1900 January 0 Greenwich Mean Noon and B has the meaning given by Spencer Jones in Monthly Notices R.A.S., Vol. 99, 541, 1939; and that the above formula define also the second. No change is contemplated or recommended in the measure of Universal Time, nor in its definition.” The ultimate purpose of this article is to explain, in simple terms, the effect that the adoption of this resolution will have on spherical and dynamical astronomy and, in particular, on the ephemerides in the Nautical Almanac. It should be noted that, in accordance with another I.A.U. resolution, Ephemeris Time (E.T.) will not be introduced into the national ephemerides until 1960. Universal Time (U.T.), previously termed Greenwich Mean Time (G.M.T.), depends both on the rotation of the Earth on its axis and on the revolution of the Earth in its orbit round the Sun. There is now no doubt as to the variability, both short-term and long-term, of the rate of rotation of the Earth; U.T. -

An Introduction to Orbit Dynamics and Its Application to Satellite-Based Earth Monitoring Systems

19780004170 NASA-RP- 1009 78N12113 An introduction to orbit dynamics and its application to satellite-based earth monitoring systems NASA Reference Publication 1009 An Introduction to Orbit Dynamics and Its Application to Satellite-Based Earth Monitoring Missions David R. Brooks Langley Research Center Hampton, Virginia National Aeronautics and Space Administration Scientific and Technical Informalion Office 1977 PREFACE This report provides, by analysis and example, an appreciation of the long- term behavior of orbiting satellites at a level of complexity suitable for the initial phases of planning Earth monitoring missions. The basic orbit dynamics of satellite motion are covered in detail. Of particular interest are orbit plane precession, Sun-synchronous orbits, and establishment of conditions for repetitive surface coverage. Orbit plane precession relative to the Sun is shown to be the driving factor in observed patterns of surface illumination, on which are superimposed effects of the seasonal motion of the Sun relative to the equator. Considerable attention is given to the special geometry of Sun- synchronous orbits, orbits whose precession rate matches the average apparent precession rate of the Sun. The solar and orbital plane motions take place within an inertial framework, and these motions are related to the longitude- latitude coordinates of the satellite ground track through appropriate spatial and temporal coordinate systems. It is shown how orbit parameters can be chosen to give repetitive coverage of the same set of longitude-latitude values on a daily or longer basis. Several potential Earth monitoring missions which illus- trate representative applications of the orbit dynamics are described. The interactions between orbital properties and the resulting coverage and illumina- tion patterns over specific sites on the Earth's surface are shown to be at the heart of satellite mission planning. -

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

Captain Vancouver, Longitude Errors, 1792

Context: Captain Vancouver, longitude errors, 1792 Citation: Doe N.A., Captain Vancouver’s longitudes, 1792, Journal of Navigation, 48(3), pp.374-5, September 1995. Copyright restrictions: Please refer to Journal of Navigation for reproduction permission. Errors and omissions: None. Later references: None. Date posted: September 28, 2008. Author: Nick Doe, 1787 El Verano Drive, Gabriola, BC, Canada V0R 1X6 Phone: 250-247-7858, FAX: 250-247-7859 E-mail: [email protected] Captain Vancouver's Longitudes – 1792 Nicholas A. Doe (White Rock, B.C., Canada) 1. Introduction. Captain George Vancouver's survey of the North Pacific coast of America has been characterized as being among the most distinguished work of its kind ever done. For three summers, he and his men worked from dawn to dusk, exploring the many inlets of the coastal mountains, any one of which, according to the theoretical geographers of the time, might have provided a long-sought-for passage to the Atlantic Ocean. Vancouver returned to England in poor health,1 but with the help of his brother John, he managed to complete his charts and most of the book describing his voyage before he died in 1798.2 He was not popular with the British Establishment, and after his death, all of his notes and personal papers were lost, as were the logs and journals of several of his officers. Vancouver's voyage came at an interesting time of transition in the technology for determining longitude at sea.3 Even though he had died sixteen years earlier, John Harrison's long struggle to convince the Board of Longitude that marine chronometers were the answer was not quite over. -

Capricious Suntime

[Physics in daily life] I L.J.F. (Jo) Hermans - Leiden University, e Netherlands - [email protected] - DOI: 10.1051/epn/2011202 Capricious suntime t what time of the day does the sun reach its is that the solar time will gradually deviate from the time highest point, or culmination point, when on our watch. We expect this‘eccentricity effect’ to show a its position is exactly in the South? e ans - sine-like behaviour with a period of a year. A wer to this question is not so trivial. For ere is a second, even more important complication. It is one thing, it depends on our location within our time due to the fact that the rotational axis of the earth is not zone. For Berlin, which is near the Eastern end of the perpendicular to the ecliptic, but is tilted by about 23.5 Central European time zone, it may happen around degrees. is is, aer all, the cause of our seasons. To noon, whereas in Paris it may be close to 1 p.m. (we understand this ‘tilt effect’ we must realise that what mat - ignore the daylight saving ters for the deviation in time time which adds an extra is the variation of the sun’s hour in the summer). horizontal motion against But even for a fixed loca - the stellar background tion, the time at which the during the year. In mid- sun reaches its culmination summer and mid-winter, point varies throughout the when the sun reaches its year in a surprising way. -

Day-Ahead Market Enhancements Phase 1: 15-Minute Scheduling

Day-Ahead Market Enhancements Phase 1: 15-minute scheduling Phase 2: flexible ramping product Stakeholder Meeting March 7, 2019 Agenda Time Topic Presenter 10:00 – 10:10 Welcome and Introductions Kristina Osborne 10:10 – 12:00 Phase 1: 15-Minute Granularity Megan Poage 12:00 – 1:00 Lunch 1:00 – 3:20 Phase 2: Flexible Ramping Product Elliott Nethercutt & and Market Formulation George Angelidis 3:20 – 3:30 Next Steps Kristina Osborne Page 2 DAME initiative has been split into in two phases for policy development and implementation • Phase 1: 15-Minute Granularity – 15-minute scheduling – 15-minute bidding • Phase 2: Day-Ahead Flexible Ramping Product (FRP) – Day-ahead market formulation – Introduction of day-ahead flexible ramping product – Improve deliverability of FRP and ancillary services (AS) – Re-optimization of AS in real-time 15-minute market Page 3 ISO Policy Initiative Stakeholder Process for DAME Phase 1 POLICY AND PLAN DEVELOPMENT Issue Straw Draft Final June 2018 July 2018 Paper Proposal Proposal EIM GB ISO Board Implementation Fall 2020 Stakeholder Input We are here Page 4 DAME Phase 1 schedule • Third Revised Straw Proposal – March 2019 • Draft Final Proposal – April 2019 • EIM Governing Body – June 2019 • ISO Board of Governors – July 2019 • Implementation – Fall 2020 Page 5 ISO Policy Initiative Stakeholder Process for DAME Phase 2 POLICY AND PLAN DEVELOPMENT Issue Straw Draft Final Q4 2019 Q4 2019 Paper Proposal Proposal EIM GB ISO Board Implementation Fall 2021 Stakeholder Input We are here Page 6 DAME Phase 2 schedule • Issue Paper/Straw Proposal – March 2019 • Revised Straw Proposal – Summer 2019 • Draft Final Proposal – Fall 2019 • EIM GB and BOG decision – Q4 2019 • Implementation – Fall 2021 Page 7 Day-Ahead Market Enhancements Third Revised Straw Proposal 15-MINUTE GRANULARITY Megan Poage Sr. -

Solar Engineering Basics

Solar Energy Fundamentals Course No: M04-018 Credit: 4 PDH Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Solar Energy Fundamentals Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. COURSE CONTENT 1. Introduction Solar energy travels from the sun to the earth in the form of electromagnetic radiation. In this course properties of electromagnetic radiation will be discussed and basic calculations for electromagnetic radiation will be described. Several solar position parameters will be discussed along with means of calculating values for them. The major methods by which solar radiation is converted into other useable forms of energy will be discussed briefly. Extraterrestrial solar radiation (that striking the earth’s outer atmosphere) will be discussed and means of estimating its value at a given location and time will be presented. Finally there will be a presentation of how to obtain values for the average monthly rate of solar radiation striking the surface of a typical solar collector, at a specified location in the United States for a given month. Numerous examples are included to illustrate the calculations and data retrieval methods presented. Image Credit: NOAA, Earth System Research Laboratory 1 • Be able to calculate wavelength if given frequency for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Be able to calculate frequency if given wavelength for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Know the meaning of absorbance, reflectance and transmittance as applied to a surface receiving electromagnetic radiation and be able to make calculations with those parameters. • Be able to obtain or calculate values for solar declination, solar hour angle, solar altitude angle, sunrise angle, and sunset angle. -

Calculating Percentages for Time Spent During Day, Week, Month

Calculating Percentages of Time Spent on Job Responsibilities Instructions for calculating time spent during day, week, month and year This is designed to help you calculate percentages of time that you perform various duties/tasks. The figures in the following tables are based on a standard 40 hour work week, 174 hour work month, and 2088 hour work year. If a recurring duty is performed weekly and takes the same amount of time each week, the percentage of the job that this duty represents may be calculated by dividing the number of hours spent on the duty by 40. For example, a two-hour daily duty represents the following percentage of the job: 2 hours x 5 days/week = 10 total weekly hours 10 hours / 40 hours in the week = .25 = 25% of the job. If a duty is not performed every week, it might be more accurate to estimate the percentage by considering the amount of time spent on the duty each month. For example, a monthly report that takes 4 hours to complete represents the following percentage of the job: 4/174 = .023 = 2.3%. Some duties are performed only certain times of the year. For example, budget planning for the coming fiscal year may take a week and a half (60 hours) and is a major task, but this work is performed one time a year. To calculate the percentage for this type of duty, estimate the total number of hours spent during the year and divide by 2088. This budget planning represents the following percentage of the job: 60/2088 = .0287 = 2.87%. -

How Long Is a Year.Pdf

How Long Is A Year? Dr. Bryan Mendez Space Sciences Laboratory UC Berkeley Keeping Time The basic unit of time is a Day. Different starting points: • Sunrise, • Noon, • Sunset, • Midnight tied to the Sun’s motion. Universal Time uses midnight as the starting point of a day. Length: sunrise to sunrise, sunset to sunset? Day Noon to noon – The seasonal motion of the Sun changes its rise and set times, so sunrise to sunrise would be a variable measure. Noon to noon is far more constant. Noon: time of the Sun’s transit of the meridian Stellarium View and measure a day Day Aday is caused by Earth’s motion: spinning on an axis and orbiting around the Sun. Earth’s spin is very regular (daily variations on the order of a few milliseconds, due to internal rearrangement of Earth’s mass and external gravitational forces primarily from the Moon and Sun). Synodic Day Noon to noon = synodic or solar day (point 1 to 3). This is not the time for one complete spin of Earth (1 to 2). Because Earth also orbits at the same time as it is spinning, it takes a little extra time for the Sun to come back to noon after one complete spin. Because the orbit is elliptical, when Earth is closest to the Sun it is moving faster, and it takes longer to bring the Sun back around to noon. When Earth is farther it moves slower and it takes less time to rotate the Sun back to noon. Mean Solar Day is an average of the amount time it takes to go from noon to noon throughout an orbit = 24 Hours Real solar day varies by up to 30 seconds depending on the time of year. -

Sidereal Time Distribution in Large-Scale of Orbits by Usingastronomical Algorithm Method

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2013): 4.438 Sidereal Time Distribution in Large-Scale of Orbits by usingAstronomical Algorithm Method Kutaiba Sabah Nimma 1UniversitiTenagaNasional,Electrical Engineering Department, Selangor, Malaysia Abstract: Sidereal Time literally means star time. The time we are used to using in our everyday lives is Solar Time.Astronomy, time based upon the rotation of the earth with respect to the distant stars, the sidereal day being the unit of measurement.Traditionally, the sidereal day is described as the time it takes for the Earth to complete one rotation relative to the stars, and help astronomers to keep them telescops directions on a given star in a night sky. In other words, earth’s rate of rotation determine according to fixed stars which is controlling the time scale of sidereal time. Many reserachers are concerned about how long the earth takes to spin based on fixed stars since the earth does not actually spin around 360 degrees in one solar day.Furthermore, the computations of the sidereal time needs to take a long time to calculate the number of the Julian centuries. This paper shows a new method of calculating the Sidereal Time, which is very important to determine the stars location at any given time. In addition, this method provdes high accuracy results with short time of calculation. Keywords: Sidereal time; Orbit allocation;Geostationary Orbit;SolarDays;Sidereal Day 1. Introduction (the upper meridian) in the sky[6]. Solar time is what the time we all use where a day is defined as 24 hours, which is The word "sidereal" comes from the Latin word sider, the average time that it takes for the sun to return to its meaning star.