A Model of Academic Mentoring to Suppoet Pasifika Achievement: An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Our Principal Important Dates Our Commitments

Otahuhu College Newsletter Friday 19 October 2019 From our Principal It has been a very good start to the final term at Otahuhu College. All students have settled into their classwork well, and in particular it is good to see the numbers staying behind for tutorials to help with preparation for exams. On Thursday I was talking to a father who said his son has started studying at home as well, this is great and must be encouraged. At this time of year extra sacrifices by the wider family which allows students to study has a long term benefit to the family and our community. This week we also found out that a number of our students have been awarded scholarships from various universities. Many of these are for substantial sums of money. So far over Otahuhu College students have been awarded over $140 000 worth of scholarships. It is important that families recognise that these scholarships are applied using Level 2 results and then confirmed by excellent Level 3 results. Important Dates 22 October Labour Day 23-26 October Tokelau Language Week 23 October Junior Boys Futsal Tournament 24-26 October Year 9&10 Leadership Camp 24 October Service Awards Evening 29 Oct – 2 Nov Smilecare Dentist 30 October Achievement Reports posted or emailed. Our Commitments Regular attendance means attending school at least ninety percent of the time. Like other top schools we expect all our students to be at school on time each day. Students who are late three times in a week will be given a detention. -

RESULTS - DAY 1 Waka Ama - Senior Regatta Sat, 02 Mar 2019

RESULTS - DAY 1 Waka Ama - Senior Regatta Sat, 02 Mar 2019 001 U16 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single Heat 1 / 2 8:55 AM Lane Time 1st Kaipara Blue Kaipara College 2 1:27.11 2nd Kaipara Red Kaipara College 3 1:27.71 3rd Manurewa Mokaela Manurewa High School 1 1:30.12 002 U16 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single Heat 2 / 2 8:58 AM Lane Time 1st Kaipara White Kaipara College 3 1:10.40 2nd TKM Nga Tapuwae Te Kura Maori o Nga Tapuwae 2 1:19.04 3rd Nga Puna O Waiorea 16 Mix Western Springs College 1 1:27.96 003 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single Heat 1 / 7 9:08 AM Lane Time 1st Auckland Girls J19 Blue/De La Auckland Girls Grammar School 1 1:03.79 2nd Nga Puna O Waiorea 19 Mix Western Springs College 3 1:20.20 3rd Otahuhu College Otahuhu College 2 1:28.87 004 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single Heat 2 / 7 9:11 AM Lane Time 1st Aorere Mixed 12 Aorere College 3 1:23.62 2nd James Cook - Puutake James Cook High School 2 1:24.20 005 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single Heat 3 / 7 9:19 AM Lane Time 1st Auckland Girls J19 Gold/ Rosmini Auckland Girls Grammar School 3 1:07.39 2nd Manurewa Keisha Manurewa High School 1 1:23.18 3rd Pukekohe High Pukekohe High School 2 1:27.90 006 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single Heat 4 / 7 9:22 AM Lane Time 1st Manurewa Mapenzi Manurewa High School 1 1:11.45 2nd Auckland Girls WHITE 2/ Rosmini Auckland Girls Grammar School 3 1:18.29 3rd Papatoetoe Papatoetoe High School 2 1:27.85 007 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single Heat 5 / 7 9:29 AM Lane Time 1st Tamaki Tamaki College 3 1:24.30 2nd TKM Nga Tapuwae Te Kura Maori o Nga Tapuwae 2 1:26.94 008 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m -

ASB Polyfest 2013 Cook Islands Stage Results

ASB Polyfest 2013 Cook Islands Stage Results NON-COMPETITION SECTION 1st Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate 2nd Epsom Girls Grammar School 3rd St Cuthbert’s College Merit Cup Auckland Girls’ Grammar School Special Awards Rakei (Costume) 1st Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate 2nd Mangere College 3rd Tangaroa College Best Composition 1st Mangere College 2nd Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate 3rd Tangaroa College Best Drummers 1st Mangere College 2nd Tangaroa College 3rd Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate Pere Pere Tane 1st Alfriston College 2nd Mangere College 3rd Otahuhu College Pere Pere Vaine 1st Mangere College 2nd Avondale College 3rd Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate Most Improved Group 1st Southern Cross Campus 2nd Alfriston College 3rd Papatoetoe High School COMPETITION SECTION Rangatira Tane/Vaine 1st Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate 2nd Mangere College 3rd Southern Cross Campus Imene Tuki/Reo Metua 1st Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate 2nd Mangere College 3rd Alfriston College Ute 1st Mangere College 2nd Sir Edmund Hillary College 3rd Tangaroa College Tua Peu Tupuna 1st Sir Edmund Hillary College 2nd Mangere College 3rd Tangaroa College Kapa Rima 1st Mangere College 2nd Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate 3rd Southern Cross Campus Ura Pa’u 1st Mangere College 2nd Tangaroa College 3rd Southern Cross Campus Overall Competitive Section 1st Mangere College 2nd Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate 3rd Tangaroa College SPEECH COMPETITION Year 9 1st Matangaro Hagai – Mangere College 2nd Tungane Tomokino - Mangere College 3rd Davinia Nati – Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate Year 10 1st Aman Ngatuakana – Papatoetoe High School 2nd Tuahinimaru Pepe – Alfriston College 3rd Ngametua Pareanga – Otahuhu College Year 11 1st Munokoa Charlie – Tangaroa College 2nd Callia Newnham – Epsom Girls’ Grammar School 3rd Louisa Nookura – Tangaroa College Year 12 1st Mahutase Rahai Nanua - Sir Edmund Hillary College 2nd Metuariki Paniora – Tangaroa College 3rd Edwina Ngatae – One Tree Hill College Year 13 1st Tumanova Wilmott – Wesley College 2nd Memory Teii – Tangaroa College 3rd Loreta Brown – Papatoetoe High School . -

Schools Advisors Territories

SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews Northland Gaynor Matthews Auckland Gaynor Matthews Coromandel Gaynor Matthews Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Bay of Plenty Angela Spice-Ridley Gisborne Angela Spice-Ridley Central Plateau Angela Spice-Ridley Taranaki Angela Spice-Ridley Hawke’s Bay Angela Spice-Ridley Wanganui, Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Welington, Kapiti, Wairarapa Sonia Tiatia Nelson / Marlborough Sonia Tiatia West Coast Sonia Tiatia Canterbury / Northern and Southern Sonia Tiatia Otago Sonia Tiatia Southland SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews NORTHLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION CONTINUED Bay of Islands College Albany Senior High School St Mary’s College Bream Bay College Alfriston College St Pauls College Broadwood Area School Aorere College St Peters College Dargaville High School Auckland Girls’ Grammar Takapuna College Excellere College Auckland Seven Day Adventist Tamaki College Huanui College Avondale College Tangaroa College Kaitaia College Baradene College TKKM o Hoani Waititi Kamo High School Birkenhead College Tuakau College Kerikeri High School Botany Downs Secondary School Waiheke High School Mahurangi College Dilworth School Waitakere College Northland College Diocesan School for Girls Waiuku College Okaihau College Edgewater College Wentworth College Opononi Area School Epsom Girls’ Grammar Wesley College Otamatea High School Glendowie College Western Springs College Pompallier College Glenfield College Westlake Boys’ High -

NCEA How Your School Rates: Auckland

NCEA How your school rates: Auckland Some schools oer other programmes such as Level 1 Year 11 NA Results not available L1 International Baccalaureate and Cambridge Exams L2 Level 2 Year 12 L3 Level 3 Year 13 point increase or decrease since 2012 UE University Entrance % of students who passed in 2013 % Decile L1 L2 L3 UE Al-Madinah School 2 84.6 -15.4 95.6 -4.4 100 0 93.3 -0.8 Albany Senior High School 10 90.7 5.3 91.7 3.2 91 11 84.1 14.5 Alfriston College 3 75.4 9 70.3 -5.1 66 -0.1 46.9 5.4 Aorere College 2 58.8 0.3 75.3 5.8 68.8 9.8 57.7 13.7 Auckland Girls’ Grammar School 5 80 5.7 81.5 3.9 68.2 -10.6 61.3 -12.4 Auckland Grammar School 10 46.1 37.8 79 2.1 66.4 1.4 54.9 -15.7 Auckland Seventh-Day Adventist High School 2 54.1 -3 45.6 -42.9 73 3.6 57.6 7.6 Avondale College 4 78.8 3.7 87.5 6.7 79.9 8.3 78.9 12.3 Baradene College of the Sacred Heart 9 98.7 5.2 100 0 97.8 4 96.3 4 Birkenhead College 6 80.5 4.4 80.1 -12.8 73.3 0.3 62 -2 Botany Downs Secondary College 10 90.6 -0.4 91.8 -0.1 88.3 8 84.8 6.9 Carmel College 10 97.4 -1.2 99.2 2 97 2.7 93.4 4.7 De La Salle College 1 79.7 9.5 75.1 5.5 59.1 -5.1 54.8 15.6 Dilworth School 4 81.7 -0.3 88.3 4.3 77.9 -7.1 71.1 -7.2 Diocesan School for Girls 10 98.3 0.2 96.6 -2.7 96.4 3.3 96.4 2.5 Edgewater College 4 89.5 8 80.6 -3.7 73.2 10.4 51.7 3.4 Elim Christian College 8 93.3 15.1 88.8 5.8 86.9 -3.2 91.3 5.1 Epsom Girls’ Grammar School 9 92.3 0.7 94.5 2.8 86.7 2.4 89.2 4.9 Glendowie College 9 90 -2.5 91.1 0.8 82.4 -3.8 81.8 1.5 Gleneld College 7 67.2 -9.3 78.6 5.4 72.5 -6.9 63.2 0.5 Green Bay High -

Past Winners

Aerobics 1996 Angela McMillan Rutherford College 1997 Angela McMillan Rutherford College 1998 Danica Aitken Epsom Girls Grammar School 1999 Danica Aitken Epsom Girls Grammar School 2000 Melissa Marcinkowski Westlake Girls High School 2001 Kylie O’Loughlin Epsom Girls Grammar School 2002 Katy McMillan Avondale College 2003 Tony Donaldson Avondale College Katy McMillan Avondale College 2004 Tony Donaldson Avondale College Eleanor Cripps Epsom Girls Grammar School 2005 Michelle Barnett Mt Albert Grammar School 2006 Jennifer Ayers Mt Albert Grammar School 2007 Honor Lock Avondale College Artistic Gymnastics 1993 Rachel Vickery Rangitoto College 1994 Nicholas Hall Wesley College Sarah Thompson Westlake Girls High School 1995 David Phillips Mt Roskill Grammar School Pania Howe Kelston Girls’ High School 1996 Wayne Laker Manurewa High School Laura Robertson Westlake Girls High School 1997 Renate M Nicholson St Cuthbert’s College 1997 Tim De Alwis Rangitoto College Laura Robertson Westlake Girls High School 1998 Tim De Alwis Rangitoto College Laura Robertson Westlake Girls High School 1999 Slarik Shorinor Glenfield College Laura Robertson Westlake Girls High School 2000 Umesh Perinpanayagam Westlake Boys High School Fiona Gunn Baradene College 2001 Daniel Good Saint Kentigern College Alethea Boon Westlake Girls High School 2002 Adrian Coman Massey High School Melynne Rameka Pukekohe High School 2003 Patrick Peng Auckland Grammar School Kate Brocklehurst Baradene College 2004 Kane Rutene Glendowie College Georgia Cervin Westlake Girls High School -

The King's Collegian 2016

AUCKLAND | NEW ZEALAND | VOLUME CXV The King’s Collegian 2016 The King’s Collegian | 2016 | Volume CXV Canice McElroy (Year 13, Middlemore) The King’s Collegian 2016 AUCKLAND | NEW ZEALAND | VOLUME CXV Contents People of King’s 3 Visual Arts 61 Cross Country and Design 67 Middle Distance Running 135 Address from the Headmaster 4 Photography 71 Cycling 138 Chairman’s Address 5 Math Olympiad 73 Equestrian 140 King’s College personnel 7 Technology Department 75 Football 141 Golf 149 Academic success 11 Hockey 150 Houses 77 Half Colours and Full Colours 12-13 Netball 159 Averill House 78 Orienteering 162 Greenbank House 80 Rowing 163 Major House 82 Campus life 15 Rugby 171 Marsden House 84 Heart of the College - our Chapel 16 Sailing 182 Middlemore House 86 Community Service at King’s 18 Skiing 183 King’s Mid-Winter Formal Parnell House 88 20 Squash 184 Peart House Counselling and Wellbeing at King’s 26 90 Swimming 185 School House Careers Centre 27 92 Tennis 186 PIHA 28 Selwyn House 94 Touch 193 Special Assemblies 29 St John’s House 96 Triathlon and Duathlon 194 Out and about 31 Taylor House 98 Water polo Te Putake Lodge 100 195 Cultural life 33 Sport 103 King’s Class of 2016 199 Cultural activities 34 Head Boy’s Address 200 Music at King’s 35 Head of Sport’s report 104 House Music 42 Sports Roll of Honour 106 Head Girl’s Address 201 Glee Club 45 Special Awards 107 King’s Class of 2016 202 Senior Drama 48 Sports Prizes and Awards 111 Autographs 230 Junior Drama 50 Archery 117 Debating 52 Athletics 118 Kapa Haka 54 Badminton 120 Library 56 Basketball 122 Literacy week 57 Clay Target Shooting 126 Creative writing at King’s 59 Cricket 127 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We acknowledge and thank all contributors for their input into the 2016 edition of The King’s Collegian. -

ZONE SWIMMING 28 Feb – 19 March 2019 North Harbour, Central/East, Central/West, Counties Manukau

ZONE SWIMMING 28 Feb – 19 March 2019 North Harbour, Central/East, Central/West, Counties Manukau NORTH HARBOUR (entries close 12 March) Tuesday 19 March, Millennium Pool, North Harbour – 25m pool 9.30 am- 9.50am warm up for a 10.00 am race start; approx. 1.00pm finish. Schools: Albany Junior High School, Albany Senior High School, Birkenhead College, Carmel College, City Impact Church School, Glenfield College, Hato Petera College, Hobsonville Point Secondary School, Kaipara College, Kingsway School, Kristin School, Long Bay College, Mahurangi College, Northcote College, Orewa College, Pinehurst School, Rangitoto College, Rosmini College, Takapuna Grammar, TKKM o Te Raki Paewhenua, Vanguard Military School, Wentworth College, Westlake Boys High, Westlake Girls High, Whangaparaoa College. CENTRAL/EAST AUCKLAND (entries close 21 February) Thursday 28 February, Diocesan School Aquatic Centre, Clyde St, Epsom – 25m pool 9.30 am- 9.50am warm up for a 10.00 am race start; approx. 1.00pm finish. Schools: Auckland Grammar, Auckland International College, Baradene College, Dilworth School, , Epsom Girls Grammar School, Glendowie College, Kings College, Marist College, McAuley College, Michael Park School, Mt Albert Grammar, Mt Hobson Middle School, Mt Roskill Grammar, Onehunga High School, Otahuhu College, One Tree Hill College, Sacred Heart College, Selwyn College, St Cuthbert’s College, St Peter’s College, Tamaki College, TKKM O Puau Te Moana Nui a Kiwa, Waiheke High School. CENTRAL/WEST AUCKLAND (entries close 12 March) Monday 18 March, West -

DRAFT LANE DRAW Waka Ama - Senior Regatta Sat, 2 Mar 2019

DRAFT LANE DRAW Waka Ama - Senior Regatta Sat, 2 Mar 2019 001 U16 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single School) Heat 1 / 2 8:30 AM 1 Manurewa High School Manurewa Mokaela 2 Kaipara College Kaipara Blue 3 Kaipara College Kaipara Red 002 U16 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single School) Heat 2 / 2 8:35 AM 1 Western Springs College Nga Puna O Waiorea 16 Mix 2 Te Kura Maori o Nga Tapuwae TKM Nga Tapuwae 3 Kaipara College Kaipara White 003 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single School) Heat 1 / 7 8:40 AM 1 Auckland Girls Grammar School Auckland Girls J19 Blue/De La Salle 2 Otahuhu College Otahuhu College 3 Western Springs College Nga Puna O Waiorea 19 Mix 004 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single School) Heat 2 / 7 8:45 AM 1 Auckland Girls Grammar School Auckland Girls WHITE 1/ De La Salle 2 2 James Cook High School James Cook - Puutake 3 Aorere College Aorere Mixed 12 005 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single School) Heat 3 / 7 8:50 AM 1 Manurewa High School Manurewa Keisha 2 Pukekohe High School Pukekohe High 3 Auckland Girls Grammar School Auckland Girls J19 Gold/ Rosmini College 006 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single School) Heat 4 / 7 8:55 AM 1 Manurewa High School Manurewa Mapenzi 2 Papatoetoe High School Papatoetoe 3 Auckland Girls Grammar School Auckland Girls WHITE 2/ Rosmini 2 007 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single School) Heat 5 / 7 9:00 AM 1 Papatoetoe High School Papatoetoe 2 Te Kura Maori o Nga Tapuwae TKM Nga Tapuwae 3 Tamaki College Tamaki 008 U19 - Mixed WT12 250m (Single School) Heat 6 / 7 9:05 AM 1 Rutherford College Rutherford Mixed 2 Epsom Girls Grammar School Epsom Girls Gold/ -

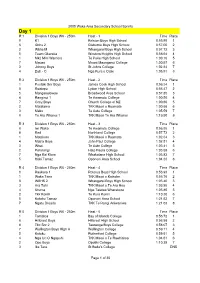

2005 Secondary School Sprints

2005 Waka Ama Secondary School Sprints Day 1 R 1 Division 1 Boys W6 - 250m Heat - 1 Time Place 8K1 Kelston Boys High School 0:55.88 1 6 Gbhs 2 Gisborne Boys High School 0:57.00 2 2 Wbhs M Whangarei Boys High School 0:57.72 3 5Team Okareka Western Heights High School 0:58.64 4 1 Mk2 Mini Warriors Te Puke High School 1:00.10 5 7 Mauao Mount Maunganui College 1:00.97 6 3 Johnny Boys St Johns College 1:02.84 7 4 Dub - C Nga Kura o Otaki 1:05.91 8 R 2 Division 1 Boys W6 - 250m Heat - 2 Time Place 1Puutaki Snr Boys James Cook High School 0:56.34 1 8 Ruatapu Lytton High School 0:56.47 2 5 Manganuiowae Broadwood Area School 0:57.85 3 4 Ranginui 1 Te Awamutu College 1:00.56 4 7Ccnz Boys Church College of NZ 1:00.60 5 2 Matatama TKK Maori o Ruamata 1:00.66 6 3 Mako Te Aute College 1:05.59 7 6 Te Ara Whanui 1 TKK Maori Te Ara Whanui 1:19.90 8 R 3 Division 1 Boys W6 - 250m Heat - 3 Time Place 6 Iwi Waka Te Awamutu College 0:56.55 1 8 Red Northland College 0:57.73 2 1 Matakoro TKK Maori o Ruamata 1:02.34 3 4 Matrix Boys John Paul College 1:02.51 4 3 Whai Te Aute College 1:03.41 5 2 Parorangi Hato Paora College 1:03.59 6 7 Nga Kai Kiore Whakatane High School 1:03.82 7 5 Hoki Tamaz Opononi Area School 1:04.33 8 R 4 Division 1 Boys W6 - 250m Heat - 4 Time Place 6 Raukura 1 Rotorua Boys High School 0:53.93 1 1 Waka Tane TKK Maori o Kaikohe 0:58.76 2 8 WBHS 2 Whangarei Boys High School 1:03.40 3 3 Ara Tahi TKK Maori o Te Ara Hou 1:03.95 4 4 Ururoa Nga Taiatea Wharekura 1:05.80 5 2 Tkk Kokiri Te Kura Kokiri 1:10.30 6 5 Kotahu Tamaz Opononi Area School 1:21.62 -

AUT School Leaver Scholarships Closing Date: 1 September

AUT School Leaver Scholarships Closing date: 1 September Auckland University of Technology (AUT) provides undergraduate scholarships to recognise student academic achievement and contribution to school and community. As well as recognising academic achievement these scholarships also recognise potential leadership ability and contribution to the school, community or cultural pursuits or sport at a representative level. CATEGORY OF AWARD AUT School Leaver Scholarships are available under the categories below, applicants are encouraged to apply for all categories for which they are eligible. • Academic Excellence: High academic achievement. • Significant Student: Contribution at a high level to the school or community. Applicants under this category must hold leadership positions and/or be active in cultural pursuits or sport at a representative level. • Kiwa: Māori and Pacific students demonstrating all-round ability and leadership potential. Applicants applying under this category must declare that they are of Māori or Pacific descent and also declare this ethnicity when applying for admission to AUT. • New Horizons: Students from a Decile 1 - 4 Auckland Region School. See list of eligible schools attached - Appendix 1 (pages 4 -5). TENURE • The scholarship is awarded for one year only. • Recipients of this award who pass all papers and meet the eligibility requirements at the completion of their first year should apply for the AUT Undergraduate Scholarship (Fees) available for all subsequent years of study in an AUT Bachelor’s degree under the categories listed above. VALUE OF AWARD An award of up to $6,500 to support full-time study in a degree programme at AUT. This will either be paid as: • Option 1: A contribution towards accommodation in an approved Hall of Residence to be paid directly to the relevant Halls of Residence; or Option 2: Payment into the student’s personal bank account in three instalments throughout the year commencing in mid-March. -

Swimming Zones 25 Feb – 15 March 2021

Swimming Zones 25 Feb – 15 March 2021 North Harbour, Central/East, Central/West, Counties Manukau NORTH HARBOUR (entries close 25 February) Thursday 4 March, Owens Glenn Pool North Harbour – 25m pool 9.00 am- 9.20am warm up for a 9.30 am race start; approx. 1.00pm finish. Schools: Albany Junior High School, Albany Senior High School, Birkenhead College, Carmel College, City Impact Church School, Glenfield College, Harbour Montessori College, Horizon School,Hato Petera College, Hobsonville Point Secondary School, Kaipara College, Kingsway School, Kristin School, Long Bay College, Mahurangi College, Northcote College, Orewa College, Pinehurst School, Rangitoto College, Rosmini College, Summit Point, Takapuna Grammar, TKKM o Te Raki Paewhenua, Vanguard Military School, Wentworth College, Westlake Boys High, Westlake Girls High, Whangaparaoa College. CENTRAL/EAST AUCKLAND (entries close 18 February) Thursday 25 February, Diocesan School Aquatic Centre, Clyde St, Epsom – 25m pool 9.00 am- 9.20am warm up for a 9.30 am race start; approx. 1.00pm finish. Schools: Auckland Grammar, Auckland International College, Baradene College, Dilworth School, Epsom Girls Grammar School, Glendowie College, Kings College, Marist College, McAuley College, Michael Park School, Mt Albert Grammar, Mt Hobson Middle School, Mt Roskill Grammar, Onehunga High School, Otahuhu College, One Tree Hill College, Sacred Heart College, Selwyn College, St Cuthbert’s College, St Peter’s College, Tamaki College, TKKM O Puau Te Moana Nui a Kiwa, Waiheke High School. CENTRAL/WEST AUCKLAND (entries close 1 March) Tuesday 9 March, West Wave Aquatic Centre – 25m pool 9.00 am- 9.20am warm up for a 9.30 am race start; approx.