Aves: Dendrocolaptidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Book

Welcome to the Ornithological Congress of the Americas! Puerto Iguazú, Misiones, Argentina, from 8–11 August, 2017 Puerto Iguazú is located in the heart of the interior Atlantic Forest and is the portal to the Iguazú Falls, one of the world’s Seven Natural Wonders and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The area surrounding Puerto Iguazú, the province of Misiones and neighboring regions of Paraguay and Brazil offers many scenic attractions and natural areas such as Iguazú National Park, and provides unique opportunities for birdwatching. Over 500 species have been recorded, including many Atlantic Forest endemics like the Blue Manakin (Chiroxiphia caudata), the emblem of our congress. This is the first meeting collaboratively organized by the Association of Field Ornithologists, Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia and Aves Argentinas, and promises to be an outstanding professional experience for both students and researchers. The congress will feature workshops, symposia, over 400 scientific presentations, 7 internationally renowned plenary speakers, and a celebration of 100 years of Aves Argentinas! Enjoy the book of abstracts! ORGANIZING COMMITTEE CHAIR: Valentina Ferretti, Instituto de Ecología, Genética y Evolución de Buenos Aires (IEGEBA- CONICET) and Association of Field Ornithologists (AFO) Andrés Bosso, Administración de Parques Nacionales (Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable) Reed Bowman, Archbold Biological Station and Association of Field Ornithologists (AFO) Gustavo Sebastián Cabanne, División Ornitología, Museo Argentino -

Evolution of the Ovenbird-Woodcreeper Assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Б/ Major Shifts in Nest Architecture and Adaptive Radiatio

JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY 37: 260Á/272, 2006 Evolution of the ovenbird-woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) / major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation Á Martin Irestedt, Jon Fjeldsa˚ and Per G. P. Ericson Irestedt, M., Fjeldsa˚, J. and Ericson, P. G. P. 2006. Evolution of the ovenbird- woodcreeper assemblage (Aves: Furnariidae) Á/ major shifts in nest architecture and adaptive radiation. Á/ J. Avian Biol. 37: 260Á/272 The Neotropical ovenbirds (Furnariidae) form an extraordinary morphologically and ecologically diverse passerine radiation, which includes many examples of species that are superficially similar to other passerine birds as a resulting from their adaptations to similar lifestyles. The ovenbirds further exhibits a truly remarkable variation in nest types, arguably approaching that found in the entire passerine clade. Herein we present a genus-level phylogeny of ovenbirds based on both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA including a more complete taxon sampling than in previous molecular studies of the group. The phylogenetic results are in good agreement with earlier molecular studies of ovenbirds, and supports the suggestion that Geositta and Sclerurus form the sister clade to both core-ovenbirds and woodcreepers. Within the core-ovenbirds several relationships that are incongruent with traditional classifications are suggested. Among other things, the philydorine ovenbirds are found to be non-monophyletic. The mapping of principal nesting strategies onto the molecular phylogeny suggests cavity nesting to be plesiomorphic within the ovenbirdÁ/woodcreeper radiation. It is also suggested that the shift from cavity nesting to building vegetative nests is likely to have happened at least three times during the evolution of the group. -

South East Brazil, 18Th – 27Th January 2018, by Martin Wootton

South East Brazil 18th – 27th January 2018 Grey-winged Cotinga (AF), Pico da Caledonia – rare, range-restricted, difficult to see, Bird of the Trip Introduction This report covers a short trip to South East Brazil staying at Itororó Eco-lodge managed & owned by Rainer Dungs. Andy Foster of Serra Dos Tucanos guided the small group. Itinerary Thursday 18th January • Nightmare of a travel day with the flight leaving Manchester 30 mins late and then only able to land in Amsterdam at the second attempt due to high winds. Quick sprint (stagger!) across Schiphol airport to get onto the Rio flight which then parked on the tarmac for 2 hours due to the winds. Another roller-coaster ride across a turbulent North Atlantic and we finally arrived in Rio De Janeiro two hours late. Eventually managed to get the free shuttle to the Linx Hotel adjacent to airport Friday 19th January • Collected from the Linx by our very punctual driver (this was to be a theme) and 2.5hour transfer to Itororo Lodge through surprisingly light traffic. Birded the White Trail in the afternoon. Saturday 20th January • All day in Duas Barras & Sumidouro area. Luggage arrived. Sunday 21st January • All day at REGUA (Reserva Ecologica de Guapiacu) – wetlands and surrounding lowland forest. Andy was ill so guided by the very capable REGUA guide Adelei. Short visit late pm to Waldanoor Trail for Frilled Coquette & then return to lodge Monday 22nd January • All day around lodge – Blue Trail (am) & White Trail (pm) Tuesday 23rd January • Early start (& finish) at Pico da Caledonia. -

State of the Amazon: Freshwater Connectivity and Ecosystem Health WWF LIVING AMAZON INITIATIVE SUGGESTED CITATION

REPORT LIVING AMAZON 2015 State of the Amazon: Freshwater Connectivity and Ecosystem Health WWF LIVING AMAZON INITIATIVE SUGGESTED CITATION Macedo, M. and L. Castello. 2015. State of the Amazon: Freshwater Connectivity and Ecosystem Health; edited by D. Oliveira, C. C. Maretti and S. Charity. Brasília, Brazil: WWF Living Amazon Initiative. 136pp. PUBLICATION INFORMATION State of the Amazon Series editors: Cláudio C. Maretti, Denise Oliveira and Sandra Charity. This publication State of the Amazon: Freshwater Connectivity and Ecosystem Health: Publication editors: Denise Oliveira, Cláudio C. Maretti, and Sandra Charity. Publication text editors: Sandra Charity and Denise Oliveira. Core Scientific Report (chapters 1-6): Written by Marcia Macedo and Leandro Castello; scientific assessment commissioned by WWF Living Amazon Initiative (LAI). State of the Amazon: Conclusions and Recommendations (chapter 7): Cláudio C. Maretti, Marcia Macedo, Leandro Castello, Sandra Charity, Denise Oliveira, André S. Dias, Tarsicio Granizo, Karen Lawrence WWF Living Amazon Integrated Approaches for a More Sustainable Development in the Pan-Amazon Freshwater Connectivity Cláudio C. Maretti; Sandra Charity; Denise Oliveira; Tarsicio Granizo; André S. Dias; and Karen Lawrence. Maps: Paul Lefebvre/Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC); Valderli Piontekwoski/Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM, Portuguese acronym); and Landscape Ecology Lab /WWF Brazil. Photos: Adriano Gambarini; André Bärtschi; Brent Stirton/Getty Images; Denise Oliveira; Edison Caetano; and Ecosystem Health Fernando Pelicice; Gleilson Miranda/Funai; Juvenal Pereira; Kevin Schafer/naturepl.com; María del Pilar Ramírez; Mark Sabaj Perez; Michel Roggo; Omar Rocha; Paulo Brando; Roger Leguen; Zig Koch. Front cover Mouth of the Teles Pires and Juruena rivers forming the Tapajós River, on the borders of Mato Grosso, Amazonas and Pará states, Brazil. -

New Species Discoveries in the Amazon 2014-15

WORKINGWORKING TOGETHERTOGETHER TO TO SHARE SCIENTIFICSCIENTIFIC DISCOVERIESDISCOVERIES UPDATE AND COMPILATION OF THE LIST UNTOLD TREASURES: NEW SPECIES DISCOVERIES IN THE AMAZON 2014-15 WWF is one of the world’s largest and most experienced independent conservation organisations, WWF Living Amazon Initiative Instituto de Desenvolvimento Sustentável with over five million supporters and a global network active in more than 100 countries. WWF’s Mamirauá (Mamirauá Institute of Leader mission is to stop the degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to build a future Sustainable Development) Sandra Charity in which humans live in harmony with nature, by conserving the world’s biological diversity, General director ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable, and promoting the reduction Communication coordinator Helder Lima de Queiroz of pollution and wasteful consumption. Denise Oliveira Administrative director Consultant in communication WWF-Brazil is a Brazilian NGO, part of an international network, and committed to the Joyce de Souza conservation of nature within a Brazilian social and economic context, seeking to strengthen Mariana Gutiérrez the environmental movement and to engage society in nature conservation. In August 2016, the Technical scientific director organization celebrated 20 years of conservation work in the country. WWF Amazon regional coordination João Valsecchi do Amaral Management and development director The Instituto de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Mamirauá (IDSM – Mamirauá Coordinator Isabel Soares de Sousa Institute for Sustainable Development) was established in April 1999. It is a civil society Tarsicio Granizo organization that is supported and supervised by the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation, and Communications, and is one of Brazil’s major research centres. -

SPLITS, LUMPS and SHUFFLES Splits, Lumps and Shuffles Alexander C

>> SPLITS, LUMPS AND SHUFFLES Splits, lumps and shuffles Alexander C. Lees Crimson-fronted Cardinal Paroaria baeri, an endemic of the Araguaia Valley. Pousada Kuryala, Félix do Araguaia Mato Grosso, Brazil, November 2008 (Bradley Davis / Birding Mato Grosso). This series focuses on recent taxonomic proposals—be they entirely new species, splits, lumps or reorganisations—that are likely to be of greatest interest to birders. This latest instalment is a bumper one, dominated by the publication of the descriptions of 15 new species (and many splits) for the Amazon in the concluding Special Volume of the Handbook of the Birds of the World (reviewed on pp. 79–80). The last time descriptions of such a large number of new species were published in a single work was in 1871, with Pelzeln’s treatise! Most of these are suboscine passerines—woodcreepers, antbirds and tyrant flycatchers, but even include a new jay. Remaining novelties include papers describing a new tapaculo (who would have guessed), a major rearrangement of Myrmeciza antbirds, more Amazonian splits and oddments involving hermits, grosbeaks and cardinals. Get your lists out! 4 Neotropical Birding 14 Above left: Mexican Hemit Phaethornis mexicanus, Finca El Pacífico, Oaxaca, Mexico, April 2007 (Hadoram Shirihai / Photographic Handbook of the Birds of the World) Above right: Ocellated Woodcreeper Xiphorhynchus ocellatus perplexus, Allpahuayo-Mishana Reserved Zone, Loreto, Peru, October 2008 (Hadoram Shirihai / Photographic Handbook of the Birds of the World) Species status for Mexican endemic to western Mexico and sister to the Hermit remaining populations of P. longirostris. Splits, Lumps and Shuffles is no stranger to A presidential puffbird taxonomic revision of Phaethornis hermits, and The Striolated Puffbird Nystalus striolatus was not readers can look forward to some far-reaching an obvious candidate for a taxonomic overhaul, future developments from Amazonia, but the with two, very morphologically similar subspecies Phaethornis under the spotlight in this issue is recognised: N. -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Safari Brazil: The Pantanal & More 2019 Sep 21, 2019 to Oct 6, 2019 Marcelo Padua & Dan Lane For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. We experienced the amazing termitaria-covered landscape of Emas National Park, where participant Rick Thompson got this evocative image, including two Aplomado Falcons, and a Pampas Deer. Brazil is a big place, and it is home to a wide variety of biomes. Among its most famous are the Amazon and the Pantanal, both occupy huge areas and have their respective hydrologies to thank for their existence. In addition to these are drier regions that cut the humid Amazon from the humid Atlantic Forest, this is known as the “Dry Diagonal,” home to the grasslands we observed at Emas, the chapada de Cipo, and farther afield, the Chaco, Pampas, and Caatinga. We were able to dip our toes into several of these incredible features, beginning with the Pantanal, one of the world’s great wetlands, and home to a wide array of animals, fish, birds, and other organisms. In addition to daytime outings to enjoy the birdlife and see several of the habitats of the region (seasonally flooded grasslands, gallery forest, deciduous woodlands, and open country that does not flood), we were able to see a wide array of mammals during several nocturnal outings, culminating in such wonderful results as seeing multiple big cats (up to three Ocelots and a Jaguar on one night!), foxes, skunks, raccoons, Giant Anteaters, and others. To have such luck as this in the Americas is something special! Our bird list from the region included such memorable events as seeing an active Jabiru nest, arriving at our lodging at Aguape to a crowd of Hyacinth Macaws, as well as enjoying watching the antics of their cousins the Blue-and-yellow Macaws. -

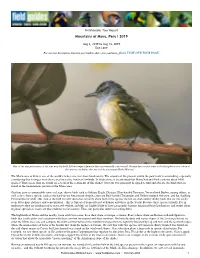

Field Guides Tour Report Mountains of Manu, Peru I 2019

Field Guides Tour Report Mountains of Manu, Peru I 2019 Aug 2, 2019 to Aug 13, 2019 Dan Lane For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. One of the star performers of the tour was this bold Yellow-rumped Antwren that was unusually extroverted! We may have gotten some of the best photos ever taken of this species, including this fine one by participant Becky Hansen! The Manu area of Peru is one of the world's richest sites for sheer biodiversity. The amount of life present within the park itself is astonishing, especially considering that it ranges from above treeline to the Amazon lowlands. In birds alone, it is estimated that Manu National Park contains about 1000 species! That's more than are found on several of the continents of this planet! Our tour was primarily designed to find and observe the birds that are found in the mountainous portion of the Manu area. Our tour gave us memorable views of large, showy birds such as Solitary Eagle, Hoatzin, Blue-banded Toucanet, Versicolored Barbet, among others, as well as less showy species such as the hard-to-see Amazonian Antpitta, the rare Buff-banded Tyrannulet and Yellow-rumped Antwren, and the skulking Peruvian Recurvebill. One look at the bird list will show that certainly about half of the species therein are drab and/or skulky birds that are not easily seen, but require patience and concentration... this is typical of tropical forest avifaunas anywhere in the world. Because these species usually live in understory, they are predisposed to not travel widely, and thus are highly likely to have geographic barriers fragment their distributions and render them regional specialists; many are thus endemic to the country. -

Phylogenetic and Ecological Determinants of the Neotropical Dawn Chorus Karl S

Proc. R. Soc. B (2006) 273, 999–1005 doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3410 Published online 17 January 2006 Phylogenetic and ecological determinants of the neotropical dawn chorus Karl S. Berg1,*, Robb T. Brumfield2 and Victor Apanius1,† 1Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, USA 2Museum of Natural Science, 119 Foster Hall, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA The concentration of avian song at first light (i.e. the dawn chorus) is widely appreciated, but has an enigmatic functional significance. One widely accepted explanation is that birds are active at dawn, but light levels are not yet adequate for foraging. In forest communities, the onset to singing should thus be predictable from the species’ foraging strata, which is ultimately related to ambient light level. To test this, we collected data from a tropical forest of Ecuador involving 57 species from 27 families of birds. Time of first song was a repeatable, species-specific trait, and the majority of resident birds, including non-passerines, sang in the dawn chorus. For passerine birds, foraging height was the best predictor of time of first song, with canopy birds singing earlier than birds foraging closer to the forest floor. A weak and opposite result was observed for non-passerines. For passerine birds, eye size also predicted time of first song, with larger eyed birds singing earlier, after controlling for body mass, taxonomic group and foraging height. This is the first comparative study of the dawn chorus in the Neotropics, and it provides the first evidence for foraging strata as the primary determinant of scheduling participation in the dawn chorus of birds. -

Panama's Canopy Tower and El Valle's Canopy Lodge

FIELD REPORT – Panama’s Canopy Tower and El Valle’s Canopy Lodge January 4-16, 2019 Orange-bellied Trogon © Ruthie Stearns Blue Cotinga © Dave Taliaferro Geoffroy’s Tamarin © Don Pendleton Ocellated Antbird © Carlos Bethancourt White-tipped Sicklebill © Jeri Langham Prepared by Jeri M. Langham VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DR., AUSTIN, TX 78746 Phone: 512-328-5221 or 800-328-8368 / Fax: 512-328-2919 [email protected] / www.ventbird.com Myriads of magazine articles have touted Panama’s incredible Canopy Tower, a former U.S. military radar tower transformed by Raúl Arias de Para when the U.S. relinquished control of the Panama Canal Zone. It sits atop 900-foot Semaphore Hill overlooking Soberania National Park. While its rooms are rather spartan, the food is Panama’s Canopy Tower © Ruthie Stearns excellent and the opportunity to view birds at dawn from the 360º rooftop Observation Deck above the treetops is outstanding. Twenty minutes away is the start of the famous Pipeline Road, possibly one of the best birding roads in Central and South America. From our base, daily birding outings are made to various locations in Central Panama, which vary from the primary forest around the tower, to huge mudflats near Panama City and, finally, to cool Cerro Azul and Cerro Jefe forest. An enticing example of what awaits visitors to this marvelous birding paradise can be found in excerpts taken from the Journal I write during every tour and later e- mail to participants. These are taken from my 17-page, January 2019 Journal. On our first day at Canopy Tower, with 5 of the 8 participants having arrived, we were touring the Observation Deck on top of Canopy Tower when Ruthie looked up and called my attention to a bird flying in our direction...it was a Black Hawk-Eagle! I called down to others on the floor below and we watched it disappear into the distant clouds. -

Assessing Bird Migrations Verônica Fernandes Gama

Assessing Bird Migrations Verônica Fernandes Gama Master of Philosophy, Remote Sensing Bachelor of Biological Sciences (Honours) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 School of Biological Sciences Abstract Birds perform many types of migratory movements that vary remarkably both geographically and between taxa. Nevertheless, nomenclature and definitions of avian migrations are often not used consistently in the published literature, and the amount of information available varies widely between taxa. Although comprehensive global lists of migrants exist, these data oversimplify the breadth of types of avian movements, as species are classified into just a few broad classes of movements. A key knowledge gap exists in the literature concerning irregular, small-magnitude migrations, such as irruptive and nomadic, which have been little-studied compared with regular, long-distance, to-and- fro migrations. The inconsistency in the literature, oversimplification of migration categories in lists of migrants, and underestimation of the scope of avian migration types may hamper the use of available information on avian migrations in conservation decisions, extinction risk assessments and scientific research. In order to make sound conservation decisions, understanding species migratory movements is key, because migrants demand coordinated management strategies where protection must be achieved over a network of sites. In extinction risk assessments, the threatened status of migrants and non-migrants is assessed differently in the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List, and the threatened status of migrants could be underestimated if information regarding their movements is inadequate. In scientific research, statistical techniques used to summarise relationships between species traits and other variables are data sensitive, and thus require accurate and precise data on species migratory movements to produce more reliable results. -

Northeast Argentina August - September 2007 Kini Roesler

TRIP REPORT Northeast Argentina August - September 2007 Kini Roesler WWW.SERIEMATOURS.COM INTRODUCCION A trip across Northeast Argentine allowed us to see one of the most impressive areas of temperate and subtropical South America. We explored many of the most amazing sceneries of the country: The pampas and savannas of Entre Rios, the Iberá Marshes and the Iguazú falls. The trip began with a short but very productive visit to Costanera Sur, the ecological reserve which is located only 10’ from the main center of Buenos Aires city. We found a large number of waterfowl and several other water related species, such as the Red Shoveler, Ringed Teal, Argentinean Lake-Duck, Masked Duck, Black- headed Duck, Red-fronted Coot, among others. While moving north, we entered woodland habitats such as the “Espinal”, in southern Entre Rios province. The “Espinal” is thorny woodland with several special birds such as the Brown Cacholote, the spectacular Scimitar- billed Woodcreeper, Short-billed Canastero and Little Thornbird, to name just some of them. We also explored the grassland areas, where two of the main target birds of the trip inhabit: Saffron-cowled Blackbird and Black- and-White Monjita. After a short visit to El Palmar National Park, an interesting palm-tree covered savanna, we moved ahead towards the Iberá Marshes. The Iberá is full of birds; however it is amazing how easy it is to see some mammals too, such as the Marsh Deer, River Otter and a famous giant rodent: the Capybaras. Speaking of wildlife, even more interesting are the caimans, the giant Yellow Anaconda and Tegu Lizard, among other fantastic vertebrates.