E Cacy of Home-Based Forti Ed Diet in Rehabilitation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality Vs Expectation)

Volume 3, Issue 2, February – 2018 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456 –2165 Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality vs Expectation) Dr. Faiza Mazhar TTS Assistant Professor Geography Department. Government College University Faisalabad, Pakistan Abstract—Sindh is our second largest populated province. Historical Populations Growth of Sindh It has a great role in culture and economy of Pakistan. Karachi the largest city of Pakistan in terms of population Census Year Total Population Urban Population also has a unique impact in development of Pakistan. Now 1951 6,047,748 29.23% according to the current census of 2017 Sindh is again 1961 8,367,065 37.85% standing on second position. Karachi is still on top of the list in Pakistan’s ten most populated cities. Population of 1972 14,155,909 40.44% Karachi has not grown on an expected rate. But it was due 1981 19,028,666 43.31% to many reasons like bad law and order situation, miss management of the Karachi and use of contraceptive 1998 29,991,161 48.75% measures. It would be wrong if it is said that the whole 2017 47,886,051 52.02% census were not conducted in a transparent manner. Source: [2] WWW.EN.WIKIPEDIA.ORG. Keywords—Component; Formatting; Style; Styling; Insert Table 1: Temporal Population Growth of Sindh (Key Words) I. INTRODUCTION According to the latest census of 2017 the total number of population in Sindh is 48.9 million. It is the second most populated province of Pakistan. -

Law and Order URC

Law and Order URC NEWSCLIPPINGS JANUARY TO JUNE 2019 LAW & ORDERS Urban Resource Centre A-2, 2nd floor, Westland Trade Centre, Block 7&8, C-5, Shaheed-e-Millat Road, Karachi. Tel: 021-4559317, Fax: 021-4387692, Email: [email protected], Website: www.urckarachi.org Facebook: www.facebook.com/URCKHI Twitter: https://twitter.com/urc_karachi 1 Law and Order URC Targeted killing: KMC employee shot dead in Hussainabad Unidentified assailants shot and killed an employee of the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC) at Hussainabad locality of Federal B Area in Central district on Monday. The deceased was struck by seven bullets in different parts of the body. Nine bullet shells of a 9mm pistol were recovered from the scene of the crime. According to police, the deceased was called to the location through a phone call. They said the late KMC employee was on his motorcycle waiting for someone. Two unidentified men killed him by opening fire at him at Hussainabad, near Okhai Memon Masjid, in the limits of Azizabad police station. The deceased, identified as Shakeel Ahmed, aged 35, son of Shafiq Ahmed, was shifted to Abbasi Shaheed Hospital for medico-legal formalities. He was a resident of house no. L-72 Sector 5C 4, North Karachi, and worked as a clerk in KMC‘s engineering department. Rangers and police officials reached the scene after receiving information of the incident. They recovered nine bullet shells of a 9mm pistol and have begun investigating the incident. According to Azizabad DSP Shaukat Raza, someone had phoned and summoned the deceased to Hussainabad, near Okhai Memon Masjid. -

Government of Sindh Finance Department

2021-22 Finance Department Government of Sindh 1 SC12102(102) GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT/ HOUSE Rs Charged: ______________ Voted: 51,652,000 ______________ Total: 51,652,000 ______________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT ____________________________________________________________________________________________ BUILDINGS ____________________________________________________________________________________________ P./ADP DDO Functional-Cum-Object Classification & Budget NO. NO. Particular Of Scheme Estimates 2021 - 2022 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Rs 01 GENERAL PUBLIC SERVICE 011 EXECUTIVE & LEGISLATIVE ORGANS, FINANCAL 0111 EXECUTIVE AND LEGISLATIVE ORGANS 011103 PROVINCIAL EXECUTIVE KQ5003 SECRETARY (GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT/ HOUSE) ADP No : 0733 KQ21221562 Constt. of Multi-storeyed Flats Phase-II at Sindh Governor's 51,652,000 House, Karachi (48 Nos.) including MT-s A12470 Others 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ Total Sub Sector BUILDINGS 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ TOTAL SECTOR GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ 2 SC12104(104) SERVICES GENERAL ADMIN & COORDINATION Rs Charged: ______________ Voted: 1,432,976,000 ______________ Total: 1,432,976,000 ______________ _____________________________________________________________________________ -

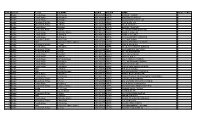

List of Dehs in Sindh

List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 1 Badin Badin 1 Abri 2 Badin Badin 2 Achh 3 Badin Badin 3 Achhro 4 Badin Badin 4 Akro 5 Badin Badin 5 Aminariro 6 Badin Badin 6 Andhalo 7 Badin Badin 7 Angri 8 Badin Badin 8 Babralo-under sea 9 Badin Badin 9 Badin 10 Badin Badin 10 Baghar 11 Badin Badin 11 Bagreji 12 Badin Badin 12 Bakho Khudi 13 Badin Badin 13 Bandho 14 Badin Badin 14 Bano 15 Badin Badin 15 Behdmi 16 Badin Badin 16 Bhambhki 17 Badin Badin 17 Bhaneri 18 Badin Badin 18 Bidhadi 19 Badin Badin 19 Bijoriro 20 Badin Badin 20 Bokhi 21 Badin Badin 21 Booharki 22 Badin Badin 22 Borandi 23 Badin Badin 23 Buxa 24 Badin Badin 24 Chandhadi 25 Badin Badin 25 Chanesri 26 Badin Badin 26 Charo 27 Badin Badin 27 Cheerandi 28 Badin Badin 28 Chhel 29 Badin Badin 29 Chobandi 30 Badin Badin 30 Chorhadi 31 Badin Badin 31 Chorhalo 32 Badin Badin 32 Daleji 33 Badin Badin 33 Dandhi 34 Badin Badin 34 Daphri 35 Badin Badin 35 Dasti 36 Badin Badin 36 Dhandh 37 Badin Badin 37 Dharan 38 Badin Badin 38 Dheenghar 39 Badin Badin 39 Doonghadi 40 Badin Badin 40 Gabarlo 41 Badin Badin 41 Gad 42 Badin Badin 42 Gagro 43 Badin Badin 43 Ghurbi Page 1 of 142 List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 44 Badin Badin 44 Githo 45 Badin Badin 45 Gujjo 46 Badin Badin 46 Gurho 47 Badin Badin 47 Jakhralo 48 Badin Badin 48 Jakhri 49 Badin Badin 49 janath 50 Badin Badin 50 Janjhli 51 Badin Badin 51 Janki 52 Badin Badin 52 Jhagri 53 Badin Badin 53 Jhalar 54 Badin Badin 54 Jhol khasi 55 Badin Badin 55 Jhurkandi 56 Badin Badin 56 Kadhan 57 Badin Badin 57 Kadi kazia -

Rapid Need Assessment Report Monsoon Rains Karachi Division Th Th 24 – 27 August 2020

Rapid Need Assessment Report Monsoon Rains Karachi Division th th 24 – 27 August 2020 Prepared by: Health And Nutrition Development Society (HANDS) Address: Plot #158, Off M9 (Karachi – Hyderabad) Motorway, Gadap Road, Karachi, Pakistan Web: www.hands.org.pk Email: [email protected] Ph: (0092-21) 32120400-9 , +92-3461117771 1 | P a g e Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Background............................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Objectives ............................................................................................................... 3 2. Methodology .................................................................................................................. 4 Situation at Model Town after Heavy Rains ....................................................................... 4 Situation at Model Town after Heavy Rains ....................................................................... 4 3. Findings ......................................................................................................................... 5 3.1. District East............................................................................................................. 6 3.2. Major disaterous events in East district ................................................................... 6 3.3. District Malir ........................................................................................................... -

Board Proceeding Ordinary Meeting Dated 15-09-2020 Present

Ch BOARD PROCEEDING ORDINARY MEETING DATED 15-09-2020 PRESENT 1 Air Vice Marshal, Nadeem Akhtar Khan Air Officer Commanding, President PAF Air Man Academy Korangi Creek 2 Mr. Nasratullah Vice President (as per court order) 3 Wing Commander, Shafiq Ahmed, Nominated OC Admin Member PAF Air Man Academy Korangi Creek 4 G.E Air. Xen Abbas Fakhruddin, Nominated PAF Air Man Academy Korangi Creek Member 5 Muhammad Farooq Ahmed Elected Member 6 Mst. Nasreen Stephen Elected Member 7 Mr. Omer Masoom Wazir, Cantt Executive Officer. Secretary Cantt Board Korangi Creek Page 1 of 18 Contents ACCOUNTS BRANCH ............................................................................................................................. 4 Item No. 01. ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Title: MONTHLY ACCOUNTS AND STATEMENT OF ARREARS ........................................ 4 Monthly statement of arrears of revenue Aug, 2020 ........................................................................................ 4 Item No. 02. ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Title: CONFIRMATION OF OFFICE NOTE UNDER SECTION 25 ......................................... 5 Item No. 03. ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Title: APPROVAL OF MOTOR -

2013-2014 Development Budget

1 SC22051(051) DEVELOPMENT (REVENUE) Rs Charged: ______________ Voted: 33,098,087,000 ______________ Total: 33,098,087,000 ______________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT ____________________________________________________________________________________________ AGRICULTURE RESEARCH ____________________________________________________________________________________________ P./ADP DDO Functional-Cum-Object Classification & Budget NO. NO. Particular Of Scheme Estimates 2013 - 2014 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Rs 04 ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 042 AGRI,FOOD,IRRIGATION,FORESTRY & FISHING 0421 AGRICULTURE 042103 AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH & EXTENSION SERVIC HD9337 DIRECTOR GENERAL AGRICULTURE RESEARCH SINDH. ADP No : 0001 HD09100137 Development and Promotion of Quality Seed through Public 134,896,000 Private Partnership in Sindh A03970 Others 134,896,000 TA9384 DY.DIRECTOR RICE RESEARCH STATION THATTA ADP No : 0002 TA12131410 Rehabilitation of Rice & Cotton Research Station Thatta 34,826,000 A03970 Others 34,826,000 KR9613 SECRETARY AGRICULTURE ADP No : 0003 HD12138010 Establishment of Agriculture Services Complex and Advisory 10,520,000 Centers in Sindh A03970 Others 10,520,000 HD9337 DIRECTOR GENERAL AGRICULTURE RESEARCH SINDH. ADP No : 0004 KA11120007 Development of Bio - Pesticide for mangement of vegetable 9,414,000 pests. A03970 Others 9,414,000 LA9404 DIRECTOR QUAID-E-AWAM ARI LARKANA ADP No : 0005 LA11120008 -

A Tribute to Heroes in Pakistan

Compassion, Resilience and Sacrifice – A tribute to Heroes in Pakistan Annual Report 2019-2020 Our Vision Create an excellence-driven, comprehensive, compassionate, free of charge, replicable healthcare system accessible to all to please Allah Subhanahu Wa Ta’ala. HealthHealth indicators indicators clearly clearly suggest suggest thatthat it itis is the the lack lack of of healthcare healthcare - [not- [not terrorismsecurity oror shortageshortage ofof waterwater oror thethe energyenergy crises] crises] - that- that is is the the greatest greatest adversityadversity facing facing Pakistan Pakistan today. today. DR.DR. ABDUL ABDUL BARI BARI KHAN KHAN ChiefChief Executive Executive Officer, Officer, Indus Indus Health Health Network Network ContentsContents MessagesMessages ChairmanChairman 04 04 ChiefChief Executive Executive Officer Officer (CEO) (CEO) 06 06 IndusIndus Health Health Network Network IndusIndus Health Health Network Network 10 10 EducationEducation 14 14 IndusIndus Hospital Hospital Research Research Center Center 20 20 PrimaryPrimary Care Care and and Global Global Health Health Initiatives Initiatives 26 26 GynecologyGynecology and and Obstetrics Obstetrics 45 45 PhysicalPhysical Health Health and and Rehabilitation Rehabilitation 48 48 TheThe Change Change Maker Maker PediatricPediatric Oncology Oncology Trailblazer: Trailblazer: Dr. ShamvilDr. Shamvil Ashraf Ashraf 55 55 CreatingCreating a new a new benchmark: benchmark: Dr. SabaDr. Saba Jamal Jamal 58 58 TheThe Indus Indus Hospital Hospital Blood Blood Center Center 60 60 ImpactImpact -

S NO. District Tehsil UC NAME SEMIS PREFIX NAME NO of STAFF 1

S NO. District Tehsil UC NAME SEMIS PREFIX NAME NO OF STAFF 1 Badin Tando Bago 1-Chabralo 401040676 GBPS KANDO FAQEER 1 2 Badin Tando Bago 8-Khadhro 401040043 GBPS HAJI ZAKIR KHOSO 2 3 Badin Tando Bago 6-Pangrio 401040084 GBPS JAMIA HANIFA SULTAN 1 4 Badin Golarchi-S.F.Rao 6-Gharo 401020165 GBPS SADDIQUE JAT 1 5 Badin Golarchi-S.F.Rao 6-Gharo 401020405 GBPS GHULAM SHAH 1 6 Badin Tando Bago 9-Dadah 401040131 GGPS BAKHO CHANDIO 1 7 Badin Golarchi-S.F.Rao 4-Tarai 401020424 GBPS ALI MUHAMMAD NOTKANI 1 8 Badin Tando Bago 3-Khalifo Qasim 401040242 GBPS AHMED ODHEJO 1 9 Badin Tando Bago 6-Pangrio 401040672 GBPS AMIR BUX LUND 1 10 Badin Tando Bago 6-Pangrio 401040223 GBPS HAJI GANHWER AHMDANI 1 11 Badin Golarchi-S.F.Rao 1-Khorwah 401020329 GBPS GUL MIR SHAH 1 12 Badin Matli 6-Ghulam Shah Laghari 401030169 GGPS JAN MUHAMMAD LAGHARI 1 13 Badin Golarchi-S.F.Rao 4-Tarai 401020357 GBPS SHADI NOTKANI 1 14 Badin Tando Bago 8-Khadhro 401040581 GBPS GHULAM HUSSAIN GURGAZ 1 15 Badin Golarchi-S.F.Rao 4-Tarai 401020526 GBPS HAJI LEEMON NOTKANI 1 16 Badin Golarchi-S.F.Rao 4-Tarai 401020419 GBPS DIL MURAD BROHI 1 17 Badin Tando Bago 9-Dadah 401040163 GGPS SULTAN SENHRO 1 18 Badin Tando Bago 4-Khoski 401040077 GBPS SOBHO KOLHI 1 19 Badin Tando Bago 10-Tando Bago 401040056 GBPS ALLAH DINO CHANDIO 1 20 Badin Tando Bago 8-Khadhro 401040537 GBPS GUL MUHAMMAD SHORO 1 21 Badin Tando Bago 9-Dadah 401040614 GBPS SACHAL MALLAH 1 22 Badin Tando Bago 8-Khadhro 401040547 GBPS KHAIR MUHAMMAD KHOSO 1 23 Badin Matli 3-Malhan 401030570 GBPS PIR BUX KHOSO 1 24 Badin Matli 12-Haji -

Preliminary Survey Report After Monsoon Rains in Karachi

Preliminary Survey Report After Monsoon Rains in Karachi Sarah Nizamani Research Fellow CBER & IBA Business Review Shah Munir Khan PhD Scholar Department of Economics Shujaat Hussain PhD Scholar Department of Economics SEPTEMBER 11, 2020 Department of Economics & Center for Business & Economic Research Institute of Business Administration 1 © Copyrights 2020 Institute of Business Administration Karachi, Pakistan Preliminary Survey Report After Monsoon Rains in Karachi Table of Contents Introduction – An overview of Karachi ............................................................................ 1 Environmental Risk and Karachi ...................................................................................... 1 Karachi - Monsoon 2020 .................................................................................................. 2 Districts of Karachi ........................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 3 Housing ......................................................................................................................... 3 Industry ......................................................................................................................... 4 Public Spaces ................................................................................................................ 4 Descriptive Characteristics of Questionnaire Respondents -

![Mini Research Are the on How to Use It in Day to Day Communication [20]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4949/mini-research-are-the-on-how-to-use-it-in-day-to-day-communication-20-5494949.webp)

Mini Research Are the on How to Use It in Day to Day Communication [20]

Sci.Int.(Lahore),29(5),1147-1153,2017 ISSN 1013-5316;CODEN: SINTE 8 1147 LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY AMONG THE STUDENTS OF GRADE-VIII STUDYING IN GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS OF SINDH 1Abdul Ghafoor Buriro, 2Shahid Hussain Mughal and 3Jawad Hussain Awan 1IBA Community College Dadu, Pakistan 2Education Department, Sukkur IBA University, Sukkur, Pakistan 3Institute of Information and Communication Technology, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan [email protected], 2shahid.mughal@iba•suk.edu.pk and [email protected] ABSTRACT: The objective of this study was to explore the language proficiency among the students of grade-VIII studying in government schools in Sindh province. The secondary data collected from the sample of all the middle schools of all districts of Sindh province through SAT-Project 2015-16 was used to reach at the findings. The students were given test booklet containing three areas of skills including mathematics and science along with language contents (Sindhi,, Urdu and English).The Results show that there is significant difference in language proficiency among the students of grade VIII studying various schools of all districts of Sindh. Key Words: Languages Proficiency, SAT Project, Middle Schools,Sindh Province, 2. Research background or context conducted by [8] reveals that teachers here in Pakistan who The increasing global advancement in ICT [1,2] and teach English have their own deficiencies in teaching. communication led the requirement of English language The results of Standardized Achievement Test(SAT),2012 making it the common language people learning. Nowadays which tested the capacity of grade VI students of Sindh more than 80% worldwide organizations make use of English province revealed that in languages Karachi was leading with language [1]. -

Ftd-Ll Lahore Samanabad Towrl Lahore, Aziz Bhatti 02(T).2021 06.01.2021 Town Lahore and Districs of Okam, Kasur, Gujranwal4 Gujrat, Hafizabad, and Mandi Bahauddin

List of Federal Insoector of Druqs as oer SRO 02(Tl/2021 Appointing Date of S, No Officer Designation Station Area jurisdiction sRo Appointment numb€r I Ms. Saadia FID.I Islamabad Industrial Triangle Kahuta Road 02(D.2021 06.01.2021 Mahwish Islamabad, District of Chakwal, Jehlum and GilgitBaltistan. 2 Mr. Khalid FID-II lslamabad Tehsil of Rawalpindi @xcluding South 02(t).2021 06.01.2021 Mehmood side of Main Avenue ofRawat Industrial Area) and Tehsil of Gujar Khan. l Mr. Babar Khan FID-III Islamabad Rawat lndustrial Area (South of Main 02(t).2021 06.01.2021 Avenue), Tehsil of Munee and Kotli Sattian, Azad Jammu & Kashmir. 4 Mst. Tehreem Sara FID-IV Islamabad Industrial Area I-9, l-10 and Nilore, ICT 02(r).2021 06.0r.2021 Excluding lndustrial Triargle Kahuta Road (Limited to Islamabad) from Sector E to Bazar of Rawat excluding Rawat Industrial area and from Toll Plaza after Sangaff to Bhara Kahu), Islamabad area Brahama Bahatar, Tehsil Taxila District ofAttock. 5 Mr. Faisal Shahzad FID.I Peshawar Districts of Nowshera, Mardan 02(D.2021 06.01.202r Abbottabad, Haripur, Mansehra, Batagram, Upper Dir, Lower Dir, Swat, Shangl4 Buner, Malakand, Kohistaru Chitral, Bajaur and Mohmand. 6 Mr. Atiq-ul-Bari FID-II Peshawar Districts of Peshawar, Kohat, Hangu, 02(D.202r 06.01 .2021 Charsadda, Swabi, Karalq Bannq Lakki Marwat, Dera Ismail Klan and Tank South Waziristan and North Waziristan. 7 Mrs. Majida FID.I Lahore Sundar industrial Estate, Lahore, 02(D.2021 06.0t.2021 Mujahid Cantonment Board Lahore, Manga- Raiwind Road Lahore, Allama lqbal Town Lahore (excluding Multan Road), Wahga Town, Lahore.