WANG-DISSERTATION.Pdf (2.823Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chinese Civil War (1927–37 and 1946–49)

13 CIVIL WAR CASE STUDY 2: THE CHINESE CIVIL WAR (1927–37 AND 1946–49) As you read this chapter you need to focus on the following essay questions: • Analyze the causes of the Chinese Civil War. • To what extent was the communist victory in China due to the use of guerrilla warfare? • In what ways was the Chinese Civil War a revolutionary war? For the first half of the 20th century, China faced political chaos. Following a revolution in 1911, which overthrew the Manchu dynasty, the new Republic failed to take hold and China continued to be exploited by foreign powers, lacking any strong central government. The Chinese Civil War was an attempt by two ideologically opposed forces – the nationalists and the communists – to see who would ultimately be able to restore order and regain central control over China. The struggle between these two forces, which officially started in 1927, was interrupted by the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, but started again in 1946 once the war with Japan was over. The results of this war were to have a major effect not just on China itself, but also on the international stage. Mao Zedong, the communist Timeline of events – 1911–27 victor of the Chinese Civil War. 1911 Double Tenth Revolution and establishment of the Chinese Republic 1912 Dr Sun Yixian becomes Provisional President of the Republic. Guomindang (GMD) formed and wins majority in parliament. Sun resigns and Yuan Shikai declared provisional president 1915 Japan’s Twenty-One Demands. Yuan attempts to become Emperor 1916 Yuan dies/warlord era begins 1917 Sun attempts to set up republic in Guangzhou. -

Rudong County Jinxin Transportation Engineering Construction Investment Co., Ltd

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. This announcement is for information purposes only and does not constitute an invitation or a solicitation of an offer to acquire, purchase or subscribe for securities or an invitation to enter into an agreement to do any such things, nor is it calculated to invite any offer to acquire, purchase or subscribe for any securities. This announcement does not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any securities in the United States or any other jurisdiction in which such offer, solicitation or sale would be unlawful prior to registration or qualification under the securities laws of any such jurisdiction. No securities may be offered or sold in the United States absent registration or an exemption from applicable registration requirements. There will be no public offering of securities in the United States. None of the Bonds will be offered to the public in Hong Kong. This announcement is not for distribution, directly or indirectly, in or into the United States. This announcement and the listing document referred to herein have been published for information purposes only as required by the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Listing Rules”) and do not constitute an offer to sell nor a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. -

Produzent Adresse Land Allplast Bangladesh Ltd

Zeitraum - Produzenten mit einem Liefertermin zwischen 01.01.2020 und 31.12.2020 Produzent Adresse Land Allplast Bangladesh Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaliganj, Gazipur, Rfl Industrial Park Rip, Mulgaon, Sandanpara, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. (Unit - 3) Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh HKD International (Cepz) Ltd. Plot # 49-52, Sector # 8, Cepz, Chittagong Bangladesh Lhotse (Bd) Ltd. Plot No. 60 & 61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Plastoflex Doo Branilaca Grada Bb, Gračanica, Federacija Bosne I H Bosnia-Herz. ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Spueu Cambodia Powerjet Home Product (Cambodia) Co., Ltd. Manhattan (Svay Rieng) Special Economic Zone, National Road 1, Sangkat Bavet, Krong Bavet, Svaay Rieng Cambodia AJS Electronics Ltd. 1st Floor, No. 3 Road 4, Dawei, Xinqiao, Xinqiao Community, Xinqiao Street, Baoan District, Shenzhen, Guangdong China AP Group (China) Co., Ltd. Ap Industry Garden, Quetang East District, Jinjiang, Fujian China Ability Technology (Dong Guan) Co., Ltd. Songbai Road East, Huanan Industrial Area, Liaobu Town, Donggguan, Guangdong China Anhui Goldmen Industry & Trading Co., Ltd. A-14, Zongyang Industrial Park, Tongling, Anhui China Aold Electronic Ltd. Near The Dahou Viaduct, Tianxin Industrial District, Dahou Village, Xiegang Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Aurolite Electrical (Panyu Guangzhou) Ltd. Jinsheng Road No. 1, Jinhu Industrial Zone, Hualong, Panyu District, Guangzhou, Guangdong China Avita (Wujiang) Co., Ltd. No. 858, Jiaotong Road, Wujiang Economic Development Zone, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Bada Mechanical & Electrical Co., Ltd. No. 8 Yumeng Road, Ruian Economic Development Zone, Ruian, Zhejiang China Betec Group Ltd. -

September 04, 1954 Chinese Foreign Ministry Intelligence Department Report on the Asian-African Conference

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified September 04, 1954 Chinese Foreign Ministry Intelligence Department Report on the Asian-African Conference Citation: “Chinese Foreign Ministry Intelligence Department Report on the Asian-African Conference,” September 04, 1954, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, PRC FMA 207-00085-19, 150-153. Obtained by Amitav Acharya and translated by Yang Shanhou. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112440 Summary: The Chinese Foreign Ministry reported Indonesia’s intention to hold the Asian-African Conference, its attitude towards the Asian-African Conference, and the possible development of the Conference. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Secret Compiled by the Intelligence Department of the Foreign Ministry (1) At the end of 1953 when Ceylon proposed to convene the Asian Prime Ministers’ Conference in Colombo, Indonesia expressed its hope of expanding the scope of the conference, including African countries. In January this year, the Indonesian Prime Minister Ali accepted the invitation to participate in the Colombo Five States’ Conference while stating that the Asian-African Conference should be listed in the agenda. (Note: During the period of the Korean War, the Asian Arab Group in the UN was rather active, which probably inspired Indonesia to put forward this proposal.) The Indonesian Foreign Minister Soenarjo believed that the Colombo Conference was the springboard to the Asian-African Conference. Ali proposed to convene the Asian-African Conference at the first day meeting of the Colombo Conference (April 28), but he didn’t get definite support or a resolution from the conference. -

SGS-Safeguards 04910- Minimum Wages Increased in Jiangsu -EN-10

SAFEGUARDS SGS CONSUMER TESTING SERVICES CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 MINIMUM WAGES INCREASED IN JIANGSU Jiangsu becomes the first province to raise minimum wages in China in 2010, with an average increase of over 12% effective from 1 February 2010. Since 2008, many local governments have deferred the plan of adjusting minimum wages due to the financial crisis. As economic results are improving, the government of Jiangsu Province has decided to raise the minimum wages. On January 23, 2010, the Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Jiangsu Province declared that the minimum wages in Jiangsu Province would be increased from February 1, 2010 according to Interim Provisions on Minimum Wages of Enterprises in Jiangsu Province and Minimum Wages Standard issued by the central government. Adjustment of minimum wages in Jiangsu Province The minimum wages do not include: Adjusted minimum wages: • Overtime payment; • Monthly minimum wages: • Allowances given for the Areas under the first category (please refer to the table on next page): middle shift, night shift, and 960 yuan/month; work in particular environments Areas under the second category: 790 yuan/month; such as high or low Areas under the third category: 670 yuan/month temperature, underground • Hourly minimum wages: operations, toxicity and other Areas under the first category: 7.8 yuan/hour; potentially harmful Areas under the second category: 6.4 yuan/hour; environments; Areas under the third category: 5.4 yuan/hour. • The welfare prescribed in the laws and regulations. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 P.2 Hourly minimum wages are calculated on the basis of the announced monthly minimum wages, taking into account: • The basic pension insurance premiums and the basic medical insurance premiums that shall be paid by the employers. -

The Chinese Phonetic Transcriptions of Old Turkish Words in the Chinese Sources from 6Th -9Th Century Focused on the Original Word Transcribed As Tujue 突厥*

The Chinese Phonetic Transcriptions of Old Title Turkish Words in the Chinese Sources from 6th - 9th Century : Focused on the Original Word Transcribed as Tujue 突厥 Author(s) Kasai, Yukiyo Citation 内陸アジア言語の研究. 29 P.57-P.135 Issue Date 2014-08-17 Text Version publisher URL http://hdl.handle.net/11094/69762 DOI rights Note Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/ Osaka University 57 The Chinese Phonetic Transcriptions of Old Turkish Words in the Chinese Sources from 6th -9th Century Focused on the Original Word Transcribed as Tujue 突厥* Yukiyo KASAI 0. Introduction The Turkish tribes which originated from Mongolia contacted since time immemorial with their various neighbours. Amongst those neighbours China, one of the most influential countries in East Asia, took note of their activities for reasons of its national security on the border areas to the North of its territory. Especially after an political unit of Turkish tribes called Tujue 突厥 had emerged in the middle of the 6th c. as the first Turkish Kaganate in Mongolia and become threateningly powerful, the Chinese dynasties at that time followed the Turks’ every move with great interest. The first Turkish Kaganate broke down in the first half of the 7th c. and came under the rule of the Chinese Tang 唐–dynasty, but * I would like first to express my sincere thanks to Prof. Dr. DESMOND DURKIN-MEISTERERNST who gave me useful advice about the contents of this article and corrected my English, too. My gratitude also goes to Prof. TAKAO MORIYASU and Prof. -

New China and Its Qiaowu: the Political Economy of Overseas Chinese Policy in the People’S Republic of China, 1949–1959

1 The London School of Economics and Political Science New China and its Qiaowu: The Political Economy of Overseas Chinese policy in the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1959 Jin Li Lim A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, September 2016. 2 Declaration: I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98,700 words. 3 Abstract: This thesis examines qiaowu [Overseas Chinese affairs] policies during the PRC’s first decade, and it argues that the CCP-controlled party-state’s approach to the governance of the huaqiao [Overseas Chinese] and their affairs was fundamentally a political economy. This was at base, a function of perceived huaqiao economic utility, especially for what their remittances offered to China’s foreign reserves, and hence the party-state’s qiaowu approach was a political practice to secure that economic utility. -

1. Adaptive Moving Shadows Detection Using Local Neighboring

www.engineeringvillage.com Citation results: 500 Downloaded: 3/5/2018 1. Adaptive moving shadows detection using local neighboring information Wang, Bingshu (School of Electronic and Computer Engineering, Shenzhen Graduate School of Peking University, Shenzhen, China); Yuan, Yule; Zhao, Yong; Zou, Wenbin Source: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), v 10117 LNCS, p 521-535, 2017, Computer Vision - ACCV 2016 Workshops, ACCV 2016 International Workshops, Revised Selected Papers Database: Compendex Compilation and indexing terms, Copyright 2018 Elsevier Inc. Data Provider: Engineering Village 2. Matrix completion based direction-of-Arrival estimation in nonuniform noise Liao, Bin (College of Information Engineering, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen; 518060, China); Guo, Chongtao; Huang, Lei; Wen, Jun Source: International Conference on Digital Signal Processing, DSP, p 66-69, March 1, 2017, Proceedings - 2016 IEEE International Conference on Digital Signal Processing, DSP 2016 Database: Compendex Compilation and indexing terms, Copyright 2018 Elsevier Inc. Data Provider: Engineering Village 3. Computing the personalized HRTFs based on weighted anthropometric parameters matching Yuan, Xiang (Shenzhen University, China); Zheng, Nengheng; Cai, Sudao Source: INTER-NOISE 2017 - 46th International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering: Taming Noise and Moving Quiet, v 2017- January, 2017, INTER-NOISE 2017 - 46th International Congress and -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

The Rise of Communism in China∗

The Rise of Communism in China∗ Ting CHENy James Kai-sing KUNGz This version, December 2020 Abstract We show that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) experienced significantly faster growth in counties occupied by the Japanese Army than those garrisoned by the Kuomingtang (KMT) during the Sino-Japanese War (c. 1940-45), using the density of middle-to-upper rank Communist cadres (5.4%) and the size of the guerilla base (10.3%) as proxies. The struggle for survival and humiliation caused by wartime sex crimes are the channels through which the CCP ascended to power. We also find that people who live in former Japanese- occupied counties today are significantly more nationalistic and exhibit greater trust in the government than those who reside elsewhere. Keywords: Communist Revolution, Peasant Nationalism, Struggle for Survival, Humilia- tion and Hatred, Puppet Troops, China JEL Classification Nos.: D74, F51, F52, N45 ∗We thank seminar participants at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and National University of Singapore for helpful comments and suggestions. James Kung acknowledges the financial support of the Research Grants Council (RGC) of Hong Kong (GRF No. 17505519) and Sein and Isaac Soude Endowment. We are solely responsible for any remaining errors. yTing Chen, Department of Economics, Hong Kong Baptist University, Renfrew Road, Hong Kong. Email: [email protected]. Phone: +852-34117546. Fax: +852-34115580. zJames Kai-sing KUNG, Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong. Email: [email protected]. Phone: +852-39177764. Fax: +852-28585614. 1 Introduction \Precisely because of the Japanese Imperial Army, which had occupied a large part of China, making Chinese people nowhere to go; once they understood, they began taking up arm- struggle, resulting in the establishment of many counter-Japanese military bases, thereby creating favorable conditions for the coming war of liberation. -

List of Manufacturers for Varner

LIST OF MANUFACTURERS FOR VARNER Country Name of Manufacturer Address City / Area Region Bangladesh 4A Yarn Dyeing Ltd Kaichabari, Baipal, DEPZ Savar Dhaka Bangladesh AKH Eco Apparels Ltd 495, Balitha, Shah Belishwer, Dhamrai Manikgonj Dhaka Bangladesh Alema Textiles Ltd Vogra, Bashan Sarak Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Anan Socks Ltd Mulaid, Maowna, Sreepur Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Ananta Casual Wear Ltd Kunia, Targach, K.B. Bazar Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Ananta Denim Technology Ltd Noyabari, Kanchpur, Sonargoan Narayangonj Dhaka Bangladesh Ananta Huaxiang Ltd Plot H2-H4, 222, 223 Adamjee EPZ Narayangonj Dhaka Bangladesh Babylon Garments & Dresses Ltd. 2-B/1 Darus Salam Road, Mirpur Dhaka Dhaka Bangladesh Bangladesh Spinners & Knitters Ltd Plot 6-11, Sector: 4/A, CEPZ Chittagong Chittagong Bangladesh Bea-Con Knit Wear Limited (Factory-2) South Shalna, Shalna Bazar Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Body Fashion Ltd Naojur, Kodda, Joydebpur Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Coast To Coast Pvt. Ltd Vill - Itahata,Union - Bason, Mouja 35 (Chandona) Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Concept Knitting Ltd Tilargati, Sataish Bazar, Tongi Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Dekko Designs Ltd East Noroshinghapur, Ashulia Savar Dhaka Bangladesh Denimach Ltd Kewa Mouja, Ward No. 5, Gorgoria Masterbari, Gazipur Dhaka Sreepur Bangladesh Denitex Limited 9/1 Karna Para Savar Dhaka Bangladesh DNV Clothing Ltd Plot No. 100/101, AEPZ, Adamjee Nagar, Siddhirgonj Narayangonj Dhaka Bangladesh Echotex Limited Chandra, Polli Bidduth, Kaliakoir Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Epyllion Style Ltd Bahadurpur, Bhawal Mirzapur, Gazipur Sadar Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Four H Lingeries Ltd B.R.T.C Bus Depot, Baluchara, Hathazari Road, Chittagong Chittagong Chittaoono Bangladesh Globus Garments Ltd K.S Complex, Mouchak, Kaliakoir Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Haesong Korea Ltd. -

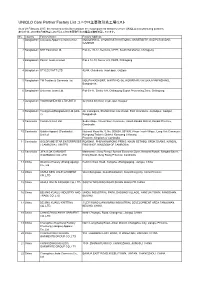

UNIQLO Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト

UNIQLO Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト As of 28 February 2017, the factories in this list constitute the major garment factories of core UNIQLO manufacturing partners. 本リストは、2017年2月末時点におけるユニクロ主要取引先の縫製工場を掲載しています。 No. Country Factory Name Factory Address 1 Bangladesh Colossus Apparel Limited unit 2 MOGORKHAL, CHOWRASTA NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, GAZIPUR SADAR, GAZIPUR 2 Bangladesh NHT Fashions Ltd. Plot no. 20-22, Sector-5, CEPZ, South Halishahar, Chittagong 3 Bangladesh Pacific Jeans Limited Plot # 14-19, Sector # 5, CEPZ, Chittagong 4 Bangladesh STYLECRAFT LTD 42/44, Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur 5 Bangladesh TM Textiles & Garments Ltd. MOUZA-KASHORE, WARD NO.-06, HOBIRBARI,VALUKA,MYMENSHING, Bangladesh. 6 Bangladesh Universal Jeans Ltd. Plot 09-11, Sector 6/A, Chittagong Export Processing Zone, Chittagong 7 Bangladesh YOUNGONES BD LTD UNIT-II 42 (3rd & 4th floor) Joydevpur, Gazipur 8 Bangladesh Youngones(Bangladesh) Ltd.(Unit- 24, Laxmipura, Shohid chan mia sharak, East Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur, 2) Bangladesh 9 Cambodia Cambo Unisoll Ltd. Seda village, Vihear Sour Commune, Ksach Kandal District, Kandal Province, Cambodia 10 Cambodia Golden Apparel (Cambodia) National Road No. 5, No. 005634, 001895, Phsar Trach Village, Long Vek Commune, Limited Kompong Tralarch District, Kompong Chhnang Province, Kingdom of Cambodia. 11 Cambodia GOLDFAME STAR ENTERPRISES ROAD#21, PHUM KAMPONG PRING, KHUM SETHBO, SROK SAANG, KANDAL ( CAMBODIA ) LIMITED PROVINCE, KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 12 Cambodia JIFA S.OK GARMENT Manhattan ( Svay Rieng ) Special Economic Zone, National Road#, Sangkat Bavet, (CAMBODIA) CO.,LTD Krong Bavet, Svay Rieng Province, Cambodia 13 China Okamoto Hosiery (Zhangjiagang) Renmin West Road, Yangshe, Zhangjiagang, Jiangsu, China Co., Ltd 14 China ANHUI NEW JIALE GARMENT WenChangtown, XuanZhouDistrict, XuanCheng City, Anhui Province CO.,LTD 15 China ANHUI XINLIN FASHION CO.,LTD.