English Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Protocol for Online Documentation of Spider Biodiversity Inventories Applied to a Mexican Tropical Wet Forest (Araneae, Araneomorphae)

Zootaxa 4722 (3): 241–269 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4722.3.2 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:6AC6E70B-6E6A-4D46-9C8A-2260B929E471 A protocol for online documentation of spider biodiversity inventories applied to a Mexican tropical wet forest (Araneae, Araneomorphae) FERNANDO ÁLVAREZ-PADILLA1, 2, M. ANTONIO GALÁN-SÁNCHEZ1 & F. JAVIER SALGUEIRO- SEPÚLVEDA1 1Laboratorio de Aracnología, Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Biología Comparada, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Circuito Exterior s/n, Colonia Copilco el Bajo. C. P. 04510. Del. Coyoacán, Ciudad de México, México. E-mail: [email protected] 2Corresponding author Abstract Spider community inventories have relatively well-established standardized collecting protocols. Such protocols set rules for the orderly acquisition of samples to estimate community parameters and to establish comparisons between areas. These methods have been tested worldwide, providing useful data for inventory planning and optimal sampling allocation efforts. The taxonomic counterpart of biodiversity inventories has received considerably less attention. Species lists and their relative abundances are the only link between the community parameters resulting from a biotic inventory and the biology of the species that live there. However, this connection is lost or speculative at best for species only partially identified (e. g., to genus but not to species). This link is particularly important for diverse tropical regions were many taxa are undescribed or little known such as spiders. One approach to this problem has been the development of biodiversity inventory websites that document the morphology of the species with digital images organized as standard views. -

A Summary List of Fossil Spiders

A summary list of fossil spiders compiled by Jason A. Dunlop (Berlin), David Penney (Manchester) & Denise Jekel (Berlin) Suggested citation: Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2010. A summary list of fossil spiders. In Platnick, N. I. (ed.) The world spider catalog, version 10.5. American Museum of Natural History, online at http://research.amnh.org/entomology/spiders/catalog/index.html Last udated: 10.12.2009 INTRODUCTION Fossil spiders have not been fully cataloged since Bonnet’s Bibliographia Araneorum and are not included in the current Catalog. Since Bonnet’s time there has been considerable progress in our understanding of the spider fossil record and numerous new taxa have been described. As part of a larger project to catalog the diversity of fossil arachnids and their relatives, our aim here is to offer a summary list of the known fossil spiders in their current systematic position; as a first step towards the eventual goal of combining fossil and Recent data within a single arachnological resource. To integrate our data as smoothly as possible with standards used for living spiders, our list follows the names and sequence of families adopted in the Catalog. For this reason some of the family groupings proposed in Wunderlich’s (2004, 2008) monographs of amber and copal spiders are not reflected here, and we encourage the reader to consult these studies for details and alternative opinions. Extinct families have been inserted in the position which we hope best reflects their probable affinities. Genus and species names were compiled from established lists and cross-referenced against the primary literature. -

(Fig. '13), Spathelia Lobulata (Fig

PHYTOGEOGHAPHIC SUHVEY OF CUBA, 11 39 monotonous sandstone ridges. The predominant soils are humic-carbonated soils on limestone, tropical brown soils on sandstone and ferritic soils on serpentine. h. Climate: Seasonal with dry winter of 1-2 or 3-4 months duration. Annual precipitation 1000-1800 mm. c. Flora: Two centres of flora development may be distinguished, both being rich in endemics. The first is the mogotes of Sierra de Nipe with about 15 endemic species, such as Hemithrinax compacta (Fig. '13), Spathelia lobulata (Fig. 6), Plinia ramosissima, Calyptranthes paradoxa, Eugenia bayatensis, E. excisa, Hydrocotyle oligantha, Matelea bayatensis, Tabebuia picotensis, T. mogotensis, Gesneria lopezii, and Jsidorea polyneura. The other centre is the group of Monte Líbano, Monte Verde and Monte Cristo which must have been the principal junction of migratory routes during the development of the Oriente flora. This area is still a rich meeting point of the limestone and serpentine floras, as well as of the semi-desert xerotherm elements. On the soils derived from serpentine the range of many species of Nipe and Cristal overlaps the distribution of Moa elements. Moreover, only at this point reach certain serpentinophilous species (Pinus cubensis, Agave shaferi) the limestone zone. Also, sorne coastal species were able to spread up to 6-700 m on the southern slopes where the xerotherm elements and the montane rainforest species meet. The three mountains possess 40 endemics altogether, sorne of them exhibiting vicariance (e.g., Siphocampylus, Gesneria). Examples of characteristic plant species are Hernandia cubensis, Auerodendron glaucescens, Salacia wrightii, Begonia libanen sis, Scolosanthus granulatus, Spermacoce exasperata, Verbesina wrightii, 3 Dorstenia, 6 Pleuro thallis, 2 Calyptranthes and 2 Ossaea species. -

Phenotypic Variation and the Behavioral Ecology of Lizards

Phenotypic Variation and the Behavioral Ecology of Lizards The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40046431 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Phenotypic Variation and the Behavioral Ecology of Lizards A dissertation presented by Ambika Kamath to The Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Biology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts March 2017 © 2017 Ambika Kamath All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Jonathan Losos Ambika Kamath Phenotypic Variation and the Behavioral Ecology of Lizards Abstract Behavioral ecology is the study of how animal behavior evolves in the context of ecology, thus melding, by definition, investigations of how social, ecological, and evolutionary forces shape phenotypic variation within and across species. Framed thus, it is apparent that behavioral ecology also aims to cut across temporal scales and levels of biological organization, seeking to explain the long-term evolutionary trajectory of populations and species by understanding short-term interactions at the within-population level. In this dissertation, I make the case that paying attention to individuals’ natural history— where and how individual organisms live and whom and what they interact with, in natural conditions—can open avenues into studying the behavioral ecology of previously understudied organisms, and more importantly, recast our understanding of taxa we think we know well. -

Fruits and Seeds of Genera in the Subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae)

Fruits and Seeds of United States Department of Genera in the Subfamily Agriculture Agricultural Faboideae (Fabaceae) Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1890 Volume I December 2003 United States Department of Agriculture Fruits and Seeds of Agricultural Research Genera in the Subfamily Service Technical Bulletin Faboideae (Fabaceae) Number 1890 Volume I Joseph H. Kirkbride, Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L. Weitzman Fruits of A, Centrolobium paraense E.L.R. Tulasne. B, Laburnum anagyroides F.K. Medikus. C, Adesmia boronoides J.D. Hooker. D, Hippocrepis comosa, C. Linnaeus. E, Campylotropis macrocarpa (A.A. von Bunge) A. Rehder. F, Mucuna urens (C. Linnaeus) F.K. Medikus. G, Phaseolus polystachios (C. Linnaeus) N.L. Britton, E.E. Stern, & F. Poggenburg. H, Medicago orbicularis (C. Linnaeus) B. Bartalini. I, Riedeliella graciliflora H.A.T. Harms. J, Medicago arabica (C. Linnaeus) W. Hudson. Kirkbride is a research botanist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, BARC West Room 304, Building 011A, Beltsville, MD, 20705-2350 (email = [email protected]). Gunn is a botanist (retired) from Brevard, NC (email = [email protected]). Weitzman is a botanist with the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, Washington, DC. Abstract Kirkbride, Joseph H., Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L radicle junction, Crotalarieae, cuticle, Cytiseae, Weitzman. 2003. Fruits and seeds of genera in the subfamily Dalbergieae, Daleeae, dehiscence, DELTA, Desmodieae, Faboideae (Fabaceae). U. S. Department of Agriculture, Dipteryxeae, distribution, embryo, embryonic axis, en- Technical Bulletin No. 1890, 1,212 pp. docarp, endosperm, epicarp, epicotyl, Euchresteae, Fabeae, fracture line, follicle, funiculus, Galegeae, Genisteae, Technical identification of fruits and seeds of the economi- gynophore, halo, Hedysareae, hilar groove, hilar groove cally important legume plant family (Fabaceae or lips, hilum, Hypocalypteae, hypocotyl, indehiscent, Leguminosae) is often required of U.S. -

A Taxonomic Review of the Trapdoor Spider Genus Myrmekiaphila (Araneae, Mygalomorphae, Cyrtaucheniidae)

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10024 Number 3596, 30 pp., 106 figures December 12, 2007 A Taxonomic Review of the Trapdoor Spider Genus Myrmekiaphila (Araneae, Mygalomorphae, Cyrtaucheniidae) JASON E. BOND1 AND NORMAN I. PLATNICK2 ABSTRACT The mygalomorph spider genus Myrmekiaphila comprises 11 species known only from the southeastern United States. The type species, M. foliata Atkinson, is removed from the synonymy of M. fluviatilis (Hentz) and placed as a senior synonym of M. atkinsoni Simon. A neotype is designated for M. fluviatilis and males of the species are described for the first time. Aptostichus flavipes Petrunkevitch is transferred to Myrmekiaphila. Six new species are described: M. coreyi and M. minuta from Florida, M. neilyoungi from Alabama, M. jenkinsi from Tennessee and Kentucky, and M. millerae and M. howelli from Mississippi. INTRODUCTION throughout the southeastern United States (fig. 1), ranging from northern Virginia along The trapdoor spider genus Myrmekiaphila the Appalachian Mountains southward (Cyrtaucheniidae, Euctenizinae) has long re- through West Virginia, Kentucky, North and mained in relative obscurity. Aside from South Carolina, Tennessee, and northern occasional species descriptions, no significant Georgia into the Southeastern Plains and taxonomic work on the group has appeared. Southern Coastal Plain of Alabama, Mis- Members of the genus are widely distributed sissippi, and Florida. The range of the genus 1 Research Associate, Division -

Brya Ebenus (L.) DC

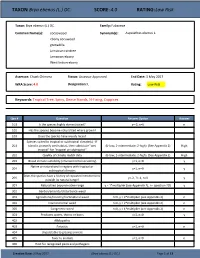

TAXON: Brya ebenus (L.) DC. SCORE: 4.0 RATING: Low Risk Taxon: Brya ebenus (L.) DC. Family: Fabaceae Common Name(s): cocoswood Synonym(s): Aspalathus ebenus L. ebony cocuwood grenadilla Jamaican raintree Jamaican-ebony West Indian-ebony Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 3 May 2017 WRA Score: 4.0 Designation: L Rating: Low Risk Keywords: Tropical Tree, Spiny, Dense Stands, N-Fixing, Coppices Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 y 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens Creation Date: 3 May 2017 (Brya ebenus (L.) DC.) Page 1 of 13 TAXON: Brya ebenus (L.) DC. -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

Spineless Spineless Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E

Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates Edited by Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Spineless Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates of the world’s Status and trends Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates Edited by Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Disclaimer The designation of the geographic entities in this report, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expressions of any opinion on the part of ZSL, IUCN or Wildscreen concerning the legal status of any country, territory, area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation Collen B, Böhm M, Kemp R & Baillie JEM (2012) Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates. Zoological Society of London, United Kingdom ISBN 978-0-900881-68-8 Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates (paperback) 978-0-900881-70-1 Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates (online version) Editors Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Zoological Society of London Founded in 1826, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is an international scientifi c, conservation and educational charity: our key role is the conservation of animals and their habitats. www.zsl.org International Union for Conservation of Nature International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) helps the world fi nd pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. www.iucn.org Wildscreen Wildscreen is a UK-based charity, whose mission is to use the power of wildlife imagery to inspire the global community to discover, value and protect the natural world. -

"MESETA DE SAN FELIPE", CAMAGÜEY, CUBA Foresta Veracruzana, Vol

Foresta Veracruzana ISSN: 1405-7247 [email protected] Recursos Genéticos Forestales México Barreto Valdés, Adelaida; Ávila Herrera, Jesús; Enríquez Salgueiro, Néstor; Oviedo, Ramona; Toscano, Bertha L.; Reyes Artiles, Grisel FLORA Y VEGETACIÓN DE LA PROPUESTA DE RESERVA FLORÍSTICA MANEJADA "MESETA DE SAN FELIPE", CAMAGÜEY, CUBA Foresta Veracruzana, vol. 10, núm. 1, 2008, pp. 9-24 Recursos Genéticos Forestales Xalapa, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=49711434002 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Foresta Veracruzana 10(1):9-24. 2008. 9 FLORA Y VEGETACIÓN DE LA PROPUESTA DE RESERVA FLORÍSTICA MANEJADA “MESETA DE SAN FELIPE”, CAMAGÜEY, CUBA Adelaida Barreto Valdés1, Jesús Ávila Herrera1, Néstor Enríquez Salgueiro1, Ramona Oviedo2, Bertha L. Toscano2 y Grisel Reyes Artiles1 Resumen Se realizaron estudios florísticos y de vegetación a mediados de la década de los años 80 y 90 del s. XX en un área de la Meseta de San Felipe localizada entre las cotas 100 y 150 con vistas a su valoración y posible inclusión en el Sistema Provincial de Áreas Protegidas (SPAP). En 1997 se presentó como propuesta de Reserva Florística Manejada en el II Taller de Áreas Protegidas celebrado en la Ciénaga de Zapata, provincia de Matanzas, en base a sus valores naturales. A inicios del s. XXI se desarrollaron evaluaciones ecológicas rápidas que permitieron obtener una visión actualizada de la situación ambiental de la zona delimitada inicialmente y se constató que, a pesar de las afectaciones sufridas en el entorno, fundamentalmente por los incendios forestales, aún existía una vegetación potencial caracterizada por cinco formaciones vegetales y una riqueza florística de 104 familias, 308 géneros y 464 taxones. -

Reconstructing the Deep-Branching Relationships of the Papilionoid Legumes

SAJB-00941; No of Pages 18 South African Journal of Botany xxx (2013) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect South African Journal of Botany journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/sajb Reconstructing the deep-branching relationships of the papilionoid legumes D. Cardoso a,⁎, R.T. Pennington b, L.P. de Queiroz a, J.S. Boatwright c, B.-E. Van Wyk d, M.F. Wojciechowski e, M. Lavin f a Herbário da Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana (HUEFS), Av. Transnordestina, s/n, Novo Horizonte, 44036-900 Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil b Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 20A Inverleith Row, EH5 3LR Edinburgh, UK c Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape, Modderdam Road, \ Bellville, South Africa d Department of Botany and Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, P. O. Box 524, 2006 Auckland Park, Johannesburg, South Africa e School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-4501, USA f Department of Plant Sciences and Plant Pathology, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 59717, USA article info abstract Available online xxxx Resolving the phylogenetic relationships of the deep nodes of papilionoid legumes (Papilionoideae) is essential to understanding the evolutionary history and diversification of this economically and ecologically important legume Edited by J Van Staden subfamily. The early-branching papilionoids include mostly Neotropical trees traditionally circumscribed in the tribes Sophoreae and Swartzieae. They are more highly diverse in floral morphology than other groups of Keywords: Papilionoideae. For many years, phylogenetic analyses of the Papilionoideae could not clearly resolve the relation- Leguminosae ships of the early-branching lineages due to limited sampling. -

Download Download

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology RESEARCH ARTICLE Vol. 30(1):10–23. 2017 Distribution and abundance of the Giant Kingbird (Tyrannus cubensis) in eastern Cuba Carlos Peña Elier Córdova Lee Newsom Nils Navarro Sergio Sigarreta Gerardo Begué Photo: Eduardo Iñigo-Elias A Special Issue on the Status of Caribbean Forest Endemics The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology Special Issue: Status of Caribbean Forest Endemics www.birdscaribbean.org/jco ISSN 1544-4953 RESEARCH ARTICLE Vol. 30(1):10–23. 2017 www.birdscaribbean.org Distribution and abundance of the Giant Kingbird (Tyrannus cubensis) in eastern Cuba Carlos Peña1,2, Elier Córdova1,3, Lee Newsom4, Nils Navarro5, Sergio Sigarreta1,6, and Gerardo Begué7 Abstract The endemic Giant Kingbird (Tyrannus cubensis) is a poorly understood and incompletely documented member of the Cuban avifauna. The bird’s distribution formerly encompassed the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands, but it has been extirpated from that portion of its former range and is now considered Endangered in Cuba. We collected and examined data on the species’ distribution, relative abundance, habitat preferences, food resources, and reproductive biology in eastern Cuba. This entailed systematic searches in the study area, as well as more intensive sampling in three known locations using a se- ries of line transects oriented along forest conservation gradients to determine relative abundance and habitat preferences of the species. Vegetation variables including canopy height, ground cover, canopy cover, and foliage density were estimated in sections of the transects. The Giant Kingbird was found to be most abundant in secondary rainforest at Monte Iberia, with 4.0 individuals/km.