Linked Data Descriptions of Debian Source Packages Using ADMS.SW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debian 1 Debian

Debian 1 Debian Debian Part of the Unix-like family Debian 7.0 (Wheezy) with GNOME 3 Company / developer Debian Project Working state Current Source model Open-source Initial release September 15, 1993 [1] Latest release 7.5 (Wheezy) (April 26, 2014) [±] [2] Latest preview 8.0 (Jessie) (perpetual beta) [±] Available in 73 languages Update method APT (several front-ends available) Package manager dpkg Supported platforms IA-32, x86-64, PowerPC, SPARC, ARM, MIPS, S390 Kernel type Monolithic: Linux, kFreeBSD Micro: Hurd (unofficial) Userland GNU Default user interface GNOME License Free software (mainly GPL). Proprietary software in a non-default area. [3] Official website www.debian.org Debian (/ˈdɛbiən/) is an operating system composed of free software mostly carrying the GNU General Public License, and developed by an Internet collaboration of volunteers aligned with the Debian Project. It is one of the most popular Linux distributions for personal computers and network servers, and has been used as a base for other Linux distributions. Debian 2 Debian was announced in 1993 by Ian Murdock, and the first stable release was made in 1996. The development is carried out by a team of volunteers guided by a project leader and three foundational documents. New distributions are updated continually and the next candidate is released after a time-based freeze. As one of the earliest distributions in Linux's history, Debian was envisioned to be developed openly in the spirit of Linux and GNU. This vision drew the attention and support of the Free Software Foundation, who sponsored the project for the first part of its life. -

Debian Developer's Reference

Debian Developer’s Reference Developer’s Reference Team <[email protected]> Andreas Barth Adam Di Carlo Raphaël Hertzog Christian Schwarz Ian Jackson ver. 3.3.9, 04 August, 2007 Copyright Notice copyright © 2004—2007 Andreas Barth copyright © 1998—2003 Adam Di Carlo copyright © 2002—2003 Raphaël Hertzog copyright © 1997, 1998 Christian Schwarz This manual is free software; you may redistribute it and/or modify it under the terms of the GNU General Public License as published by the Free Software Foundation; either version 2, or (at your option) any later version. This is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but without any warranty; without even the implied warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. See the GNU General Public License for more details. A copy of the GNU General Public License is available as /usr/share/common-licenses /GPL in the Debian GNU/Linux distribution or on the World Wide Web at the GNU web site (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/gpl.html). You can also obtain it by writing to the Free Software Foundation, Inc., 51 Franklin Street, Fifth Floor, Boston, MA 02110-1301, USA. i Contents 1 Scope of This Document 1 2 Applying to Become a Maintainer 3 2.1 Getting started ....................................... 3 2.2 Debian mentors and sponsors .............................. 4 2.3 Registering as a Debian developer ........................... 4 3 Debian Developer’s Duties 7 3.1 Maintaining your Debian information ......................... 7 3.2 Maintaining your public key ............................... 7 3.3 Voting ............................................ 8 3.4 Going on vacation gracefully .............................. 8 3.5 Coordination with upstream developers ....................... -

A Brief History of Debian I

A Brief History of Debian i A Brief History of Debian A Brief History of Debian ii 1999-2020Debian Documentation Team [email protected] Debian Documentation Team This document may be freely redistributed or modified in any form provided your changes are clearly documented. This document may be redistributed for fee or free, and may be modified (including translation from one type of media or file format to another or from one spoken language to another) provided that all changes from the original are clearly marked as such. Significant contributions were made to this document by • Javier Fernández-Sanguino [email protected] • Bdale Garbee [email protected] • Hartmut Koptein [email protected] • Nils Lohner [email protected] • Will Lowe [email protected] • Bill Mitchell [email protected] • Ian Murdock • Martin Schulze [email protected] • Craig Small [email protected] This document is primarily maintained by Bdale Garbee [email protected]. A Brief History of Debian iii COLLABORATORS TITLE : A Brief History of Debian ACTION NAME DATE SIGNATURE WRITTEN BY September 14, 2020 REVISION HISTORY NUMBER DATE DESCRIPTION NAME A Brief History of Debian iv Contents 1 Introduction -- What is the Debian Project? 1 1.1 In the Beginning ................................................... 1 1.2 Pronouncing Debian ................................................. 1 2 Leadership 2 3 Debian Releases 3 4 A Detailed History 6 4.1 The 0.x Releases ................................................... 6 4.1.1 The Early Debian Packaging System ..................................... 7 4.2 The 1.x Releases ................................................... 7 4.3 The 2.x Releases ................................................... 8 4.4 The 3.x Releases ................................................... 8 4.5 The 4.x Releases .................................................. -

Infraestructura Distribuida Para La Construcción De Paquetes Debian

INFRAESTRUCTURA DISTRIBUIDA PARA LA CONSTRUCCIÓN DE PAQUETES DEBIAN UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA-LA MANCHA ESCUELA SUPERIOR DE INFORMÁTICA INGENIERÍA EN INFORMÁTICA PROYECTO FIN DE CARRERA Infraestructura distribuida para la construcción de paquetes Debian José Luis Sanroma Tato Septiembre, 2014 UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA-LA MANCHA ESCUELA SUPERIOR DE INFORMÁTICA Departamento de Tecnologías y Sistemas de Información PROYECTO FIN DE CARRERA Infraestructura distribuida para la construcción de paquetes Debian Autor: José Luis Sanroma Tato Director: Dr. Francisco Moya Fernández Septiembre, 2014 José Luis Sanroma Tato Ciudad Real – Spain E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.icebuilder.org c 2014 José Luis Sanroma Tato Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". Se permite la copia, distribución y/o modificación de este documento bajo los términos de la Licencia de Documentación Libre GNU, versión 1.3 o cualquier versión posterior publicada por la Free Software Foundation; sin secciones invariantes. Una copia de esta licencia esta incluida en el apéndice titulado «GNU Free Documentation License». Muchos de los nombres usados por las compañías para diferenciar sus productos y servicios son reclamados como marcas registradas. Allí donde estos nombres aparezcan en este documento, y cuando el autor haya sido informado de esas marcas registradas, los nombres estarán escritos en mayúsculas o como nombres propios. -

Debian Reference

Guía de referencia Debian Osamu Aoki <[email protected]> Coordinador de la traducción al español: Walter O. Echarri <[email protected]> ‘Autores’ en la página 251 CVS, dom sep 25 04:22:02 UTC 2005 Resumen Esta Guía de referencia Debian (http://qref.sourceforge.net/) intenta proporcionar un repaso amplio del sistema Debian al igual que una guía de usuario post-instalación Abarca diversos aspectos de la administración del sistema mediante ejemplos que utilizan comandos de la shell. Se brindan tutoriales, trucos e información sobre diversos temas: conceptos bási- cos del sistema Debian, consejos para la instalación del sistema, administración de paquetes Debian, el kernel de Linux en Debian, puesta a punto del sistema, creación de una puerta de enlace (gateway), editores de texto, CVS, programación y GnuPG para usuarios que no son desarrolladores. Nota de Copyright Copyright © 2001–2005 by Osamu Aoki <[email protected]> Copyright (Chapter 2) © 1996–2001 by Software in the Public Interest. Este documento puede ser usado en los términos descritos en la Licencia Pública GNU versión 2 o posterior. (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/gpl.html) Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this document provided the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies. Permission is granted to copy and distribute modified versions of this document under the conditions for verbatim copying, provided that the entire resulting derived work is distributed under the terms of a permission notice identical to this one. Permission is granted to copy and distribute translations of this document into another lan- guage, under the above conditions for modified versions, except that this permission notice may be included in translations approved by the Free Software Foundation instead of in the original English. -

Evidence from the Debian Case

The end of communities of practice in open source projects? : evidence from the Debian case Citation for published version (APA): Sadowski, B. M., & Rasters, G. (2005). The end of communities of practice in open source projects? : evidence from the Debian case. (ECIS working paper series; Vol. 200509). Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2005 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Debian Developer's Reference

Debian Developer’s Reference Developer’s Reference Team, Andreas Barth, Adam Di Carlo, Raphaël Hertzog, Christian Schwarz, and Ian Jackson August 22, 2009 Debian Developer’s Reference by Developer’s Reference Team, Andreas Barth, Adam Di Carlo, Raphaël Hertzog, Christian Schwarz, and Ian Jackson Published unknown Copyright © 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 Andreas Barth Copyright © 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 Adam Di Carlo Copyright © 2002, 2003 Raphaël Hertzog Copyright © 1997, 1998 Christian Schwarz This manual is free software; you may redistribute it and/or modify it under the terms of the GNU General Public License as published by the Free Software Foundation; either version 2, or (at your option) any later version. This is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but without any warranty; without even the implied warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. See the GNU General Public License for more details. A copy of the GNU General Public License is available as /usr/share/common-licenses/GPL in the Debian GNU/Linux distribution or on the World Wide Web at the GNU web site. You can also obtain it by writing to the Free Software Foundation, Inc., 51 Franklin Street, Fifth Floor, Boston, MA 02110-1301, USA. If you want to print this reference, you should use the pdf version. This page is also available in French. ii Contents 1 Scope of This Document1 2 Applying to Become a Maintainer3 2.1 Getting started . .3 2.2 Debian mentors and sponsors . .3 2.3 Registering as a Debian developer . .4 3 Debian Developer’s Duties7 3.1 Maintaining your Debian information . -

Tape Automation Scalar Key Manager, Software Release 2.4 Open Source Software Licenses

Tape Automation Scalar Key Manager, Software Release 2.4 Open Source Software Licenses Open Source Software (OSS) Licenses for: • Scalar Key Manager, Software Release 2.4. The software installed in this product contains Open Source Software (OSS). OSS is third party software licensed under separate terms and conditions by the supplier of the OSS. Use of OSS is subject to designated license terms and the following OSS license disclosure lists the open source components and applicable licenses that are part of the Scalar Key Manager. The Scalar Key Manager, Software Release 2.4, is delivered with Ubuntu 12.04 as a base operat- ing system. Individual packages that comprise the Ubuntu distribution come with their own li- censes; the texts of these licenses are located in the packages' source code and permit you to run, copy, modify, and redistribute the software package (subject to certain obligations in some cases) both in source code and binary code forms. The following table lists open-source software components used in the Scalar Key Manager® release 2.4 that have been added to the base operating system, patched, or otherwise included with the product. For each component, the associated licenses are provided. Upon request, Quan- tum will furnish a DVD containing source code for all of these open-source modules for the ad- ditional packages listed here. The source for the ubuntu-12.04.5-alternate-amd64.iso can current- ly be found at: http://cdimage.ubuntu.com/releases/12.04/release/source/ To order a copy of the source code covered by an open source license, or to obtain information and instructions in support of any open source license terms, contact the Global Call Center: • In the USA, call 1-800-284-5101. -

Machine Learning

Machine Learning Hands-On for Developers and Technical Professionals Jason Bell ffi rs.indd 10:2:39:AM 10/06/2014 Page i Machine Learning: Hands-On for Developers and Technical Professionals Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 10475 Crosspoint Boulevard Indianapolis, IN 46256 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada ISBN: 978-1-118-88906-0 ISBN: 978-1-118-88939-8 (ebk) ISBN: 978-1-118-88949-7 (ebk) Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: The publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifi cally disclaim all warranties, including without limitation warranties of fi tness for a particular purpose. -

Do Not Translate Or Localize

DO NOT TRANSLATE OR LOCALIZE *********************************************************************** For the avoidance of doubt, except that if any license choice other than GPL or LGPL is available it will apply instead, Sun elects to use only the Lesser General Public License version 2.1 (LGPLv2.1) at this time for any software where a choice of LGPL license versions is made available with the language indicating that LGPLv2.1 or any later version may be used, or where a choice of which version of the LGPL is applied is otherwise unspecified. If no license choice other than GPL is available, Sun elects to use only the General Public License version 2 (GPLv2) at this time for any software where a choice of GPL license versions is made available with the language indicating that GPLv2 or any later version may be used, or where a choice of which version of the GPL is applied is otherwise unspecified. %%The following software may be included in this product: pam_radius_auth Use of any of this software is governed by the terms of the license below: * This program is free software; you can redistribute it and/or modify * it under the terms of the GNU General Public License as published by * the Free Software Foundation; either version 2 of the License, or * (at your option) any later version. * * This program is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, * but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of Sun Microsystems, Inc. www.sun.com Part No. 820-4757-10 March 2008, Revision A * MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. -

Free for All How Linux and the Free Software Move- Ment Undercut the High-Tech Titans

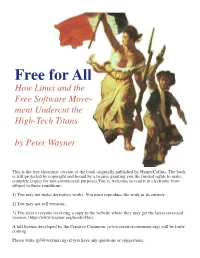

Free for All How Linux and the Free Software Move- ment Undercut the High-Tech Titans by Peter Wayner This is the free electronic version of the book originally published by HarperCollins. The book is still protected by copyright and bound by a license granting you the limited rights to make complete copies for non-commercial purposes.You’re welcome to read it in electronic form subject to these conditions: 1) You may not make derivative works. You must reproduce the work in its entirety. 2) You may not sell versions. 3) You refer everyone receiving a copy to the website where they may get the latest corrected version. (http://www.wayner.org/books/ffa/). A full license developed by the Creative Commons (www.creativecommons.org) will be forth- coming. Please write ([email protected]) if you have any questions or suggestions. Disappearing Cryptography, 2nd Edition Information Hiding: Steganography & Watermarking by Peter Wayner ISBN 1-55860-769-2 $44.95 To order, visit: http://www.wayner.org/books/discrypt2/ Disappearing Cryptography, Second Edition describes how to take words, sounds, or images and hide them in digital data so they look like other words, sounds, or images. When used properly, this powerful technique makes it almost impossible to trace the author and the recipient of a message. Conversations can be sub- merged in the flow of information through the Internet so that no one can know if a conversation exists at all. This full revision of the best-selling first edition “Disappearing Cryptography is a witty and enter- describes a number of different techniques to hide taining look at the world of information hiding. -

The End of Communities of Practice in Open Source Projects? Evidence from the Debian Case

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics The end of communities of practice in open source projects? Evidence from the Debian case. B.M. Sadowski & G. Rasters Eindhoven Centre for Innovation Studies, The Netherlands Working Paper 05.09 Department of Technology Management Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, The Netherlands July 2005 The End of Communities of Practice in Open Source Projects? Evidence from the Debian case Keywords: Open Source Software community, Community of Practice, Team- based Projects, Debian Abstract The paper explores the notion of team-based work that has recently been introduced in the discussion within Open Source Community (OSS) projects. In contrast to open boundaries within a community of practice, project-based teams refer to a relatively small group of collaborating people who operate within clear and relatively stable team boundaries and fit particular functions, roles, and norms. The history of Debian, in particular the discussion in recent leadership elections, has shown that there is an interest in team-based work. After characterizing the stages in the evolution of the Debian project, team-based work is considered as providing novel solutions to the problem of release management and growth problems within the Debian community. 2 1. Introduction Open source communities face a dilemma as they have to be organized in a way that allows the creation of new knowledge while at the same time facilitating development of new stable releases of a particular 'free' software package. Open source software (OSS) communities have been characterized as being open, i.e.