POCO – All Music Guide One of the First and Longest-Lasting Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eagles Tribute Band Set for Suffolk Center

Eagles Tribute Band Set for Suffolk Center 7 Bridges: The Ultimate EAGLES Experience will give fans of the classic rock band the Eagles a chance to re-live the greatest hits of the band who had one of the top 20 best-selling albums of the 20th century. 7 Bridges will perform at the Suffolk Center for Cultural Arts on Saturday, Nov. 12 at 8:00 p.m. Eagles fans will hear all their favorite songs. Country-tinged early favorites, like ‘Lying Eyes’, ‘Best of My Love’, and ‘Desperado’ mesh well with the later period rock songs like ‘Life in the Fast Lane’, ‘Heartache Tonight’, and ‘Hotel California’ which are timeless classics audiences love to hear. Other crowd-pleasers include ‘Take It Easy’, ‘Witchy Woman’, ‘Peaceful Easy Feeling’, and ‘Already Gone’. The Eagles had five number one singles, six number one albums, six Grammy Awards, five American Music Awards. Members of 7 Bridges give the audience a stunningly accurate tribute that faithfully re-creates the experience of an Eagles concert. One reviewer wrote, “Close your eyes and listen to 7 Bridges... WOW, they could be the real Eagles. Vocally and visually perfect. A great group of musicians who are consummate professionals. The ultimate Eagles experience.” The performance is sponsored by Duke Automotive. Ticket prices for the performance are $35 and $40. Suffolk Center members at the Sponsor level and above receive a 10% discount on ticket prices. Group discounts are available when purchasing 10 or more tickets. Contact the box office at 923-3900 or purchase tickets online at www.suffolkcenter.org. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Execulive Turnlable Insidetrack

66 Lote General News MERCER ELLINGTON BOOKED $25,000 Grant To Ensure InsideTrack George Wein still hopes to open an innovative jazz then went on sale. The entertainers appeared before an Duke's Music At Newport showcase in New York similar to his successful Boston estimated 62,000 persons -most of them getting their Storyville jazz club of the 1950s, but the planned Feb. 28 first taste of country music. NEW YORK -Audiences at this George Wein has been able to sal- bow may be delayed. As a place where musicians could AI Bramy, San Francisco distribution pioneer, is con- year's Newport Jazz Festival will be vage at least some of the concerts for meet, jam and try out new ideas, it was to be housed in valescing at his home from a minor heart attack. He will treated to a series of concerts cov- Newport with relative ease. the basement of Frank's Place on East 48th St. in Man- return to Eric Mainland as general manager in about ering the early works of the late The first of the four concerts will hattan. four weeks. Duke Ellington, thanks to a $25,000 cover Ellington's music during the At midpoint of Bette Midler's four -month national W.F. "Jim" Myers, SESAC vice president and di- grant from the National Endowment 1920s, and the second and third will tour, gross is reported as topping $1.2 million, including rector of international relations, returns to the U.S. the for the Arts. follow his growth and style through a record $403,000 for six days at Los Angeles' Chandler end of the month following visits to Paris, Helsinki, The concerts were originally the 1930s and 1940s. -

Desperado Set to Fill Hht…

PRESS RELEASE – February 23, 2017 DESPERADO SET TO FILL HHT...AGAIN The band DESPERADO has a reputation for an amazing recreation of the classic sound of THE EAGLES. If you close your eyes, you would swear you were listening to one of your favorite LPs from the 70's. On Saturday March 4th at 7:00 pm you can experience that feeling too. In 2015, DESPERADO was the first group to sell out their performance at the fledgling Historic Hemet Theatre. Last year, their return visit was one of only two concerts that filled the auditorium to capacity. Now that the theatre is filling the house regularly, this appearance will certainly be no exception. With five lead vocalists and instrumentalists who have honed their musical skills in a variety of professional projects, "DESPERADO" is truly a cut above -- performing with all live sound (no backing tracks). Singing the Eagles soaring harmonies while executing the guitar parts and rhythm track to perfection, "Desperado" challenges the listener to tell the difference between what is being played live and the original versions of the songs. Leader and founding member Aaron Broering spent years putting together just the right combination of musicians to fulfill his dream of performing these well-crafted songs with the highest of skill. Recruiting performers who have traveled the world performing with The Beach Boys, David Ruffin of the Temptations, Sam Moore of Sam & Dave, and with Eagles Timothy B Schmit, Don Felder, and J.D. Souther, Desperado truly is "The Premier Eagles Tribute." Tribute to The Eagles is the third in the 2017 "Tribute Mania" concert series that is helping bring the Historic Hemet Theatre back to life. -

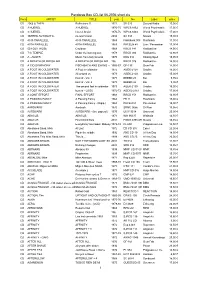

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

Heavy Metal and Classical Literature

Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 ROCKING THE CANON: HEAVY METAL AND CLASSICAL LITERATURE By Heather L. Lusty University of Nevada, Las Vegas While metalheads around the world embrace the engaging storylines of their favorite songs, the influence of canonical literature on heavy metal musicians does not appear to have garnered much interest from the academic world. This essay considers a wide swath of canonical literature from the Bible through the Science Fiction/Fantasy trend of the 1960s and 70s and presents examples of ways in which musicians adapt historical events, myths, religious themes, and epics into their own contemporary art. I have constructed artificial categories under which to place various songs and albums, but many fit into (and may appear in) multiple categories. A few bands who heavily indulge in literary sources, like Rush and Styx, don’t quite make my own “heavy metal” category. Some bands that sit 101 Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 on the edge of rock/metal, like Scorpions and Buckcherry, do. Other examples, like Megadeth’s “Of Mice and Men,” Metallica’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” and Cradle of Filth’s “Nymphetamine” won’t feature at all, as the thematic inspiration is clear, but the textual connections tenuous.1 The categories constructed here are necessarily wide, but they allow for flexibility with the variety of approaches to literature and form. A segment devoted to the Bible as a source text has many pockets of variation not considered here (country music, Christian rock, Christian metal). -

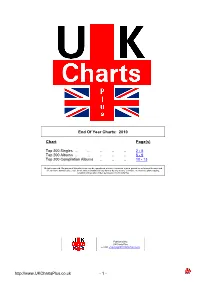

End of Year Charts: 2010

End Of Year Charts: 2010 Chart Page(s) Top 200 Singles .. .. .. .. .. 2 - 5 Top 200 Albums .. .. .. .. .. 6 - 9 Top 200 Compilation Albums .. .. .. 10 - 13 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site or forum, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Published by: UKChartsPlus e-mail: [email protected] http://www.UKChartsPlus.co.uk - 1 - Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 2010 7” Vinyl only Download only Entry Date 2010 2009 2008 2007 Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) (w/e) High Wks 1 -- -- -- LOVE THE WAY YOU LIE - Eminem featuring Rihanna Interscope (2748233) 03/07/2010 2 28 2 -- -- -- WHEN WE COLLIDE - Matt Cardle Syco (88697837092) 25/12/2010 13 3 3 -- -- -- JUST THE WAY YOU ARE (AMAZING) - Bruno Mars Elektra ( USAT21001269) 02/10/2010 12 15 4 -- -- -- ONLY GIRL (IN THE WORLD) - Rihanna Def Jam (2755511) 06/11/2010 12 10 5 -- -- -- OMG - Usher featuring will.i.am LaFace ( USLF20900103) 03/04/2010 1 41 6 -- -- -- FIREFLIES - Owl City Island ( USUM70916628) 16/01/2010 13 51 7 -- -- -- AIRPLANES - B.o.B featuring Hayley Williams Atlantic (AT0353CD) 12/06/2010 1 31 8 -- -- -- CALIFORNIA GURLS - Katy Perry featuring Snoop Dogg Virgin (VSCDT2013) 03/07/2010 12 28 WE NO SPEAK AMERICANO - Yolanda Be Cool vs D Cup 9 -- -- -- 17/07/2010 1 26 All Around The World/Universal -

The New Hampshire, Vol. 66, No. 2 (Sep. 9, 1975)

the new Hampshire Volume 66 Number 2 Tuesday, September 9, 1975 " Durham, N.H. Traffic, ski team problems aired doesn’t know what’s going on. By Rich Mori There has been a lot of misinfor The parking problem and the mation handed out by them and elimination of the ski team dom the residence people; misinfor inated discussion at the first mation concerning parking stick Student Caucus meeting Sunday, ers, availability of parking, and n i g h t . the process of petition.” The Traffic Bureau’s new peo- Farnham urged all student sen cedure of monitoring cars by sta ators to tell their constituants tioning patrolmen in four booths “to see me at the student gov around campus, the elimination ernment office before paying of parking spaces, and the park what they believe are unjust ing status of cars owned by mini fines. I’ve seen students with dorm students has caused a $100 to $300 in fines last year great deal of confusion among and they had to pay them re members of the university com gardless of whether they had a munity. legitimate reason for parking David Famham, a member of their cars where they were Student Government who is also tagged, because the registrar can a member of the University withold their grades.” Parking and Traffic Committee Later he criticized the resi said that “the system of student dence office for telling large Ever have thirteen roommates? Fourteen residents of Randall Hall live in this commune type input did not work. Last semes numbers of perspective mini build-up. -

Yesterday and Today Records March 2007 Newsletter

March 2007 Newsletter ----------------------------------- Yesterday & Today Records 255A Church St Parramatta NSW 2150 phone/fax: (02) 96333585 email: [email protected] web: www.yesterdayandtoday.com.au ------------------------------------------------------ Postage: 1 cd $2.00/ 2cd $3/ 3-4 cds $5.80* (*Recent Australia Post price increase.) Guess what? We have just celebrated our 18th anniversary. Those who try things we recommend are rewarded. We have stayed in business for one reason and that is we have never attempted to appeal to the lowest common denominator as mainstream outlets do. At the same time we recognise that people do have different tastes and to some CMT is actually good. We also appeal to those people and offer many mainstream items in our bargain bin. But the legends and true country music are our bread butter and will always be. If you see something you think you may like but are worried let us know. If you pass our inquisition we may be able to send it on a sale or return basis. I say inquisition because if your favourite artists are SheDaisy and Rascal Flatts we certainly aren’t going to risk something as precious as Justin Trevino. By the same token we believe great music is timeless and knows no bounds. People may think chuck steak is good until they try the best rump! Recently I had the pleasure of seeing Dale Watson. Before hand I had the added pleasure of sitting in with my compatriot Eddie White (a.k.a. “The Cosmic Cowboy”) for an interview at the 2RRR Studios. Dale is a humble, engaging and extremely likeable man with a passion for tradition. -

Take 2 Dance Band Current Song List

TAKE 2 DANCE BAND CURRENT PLAYLIST 24K MAGIC BRUNO MARS 25 OR 6 TO 4 CHICAGO AFRICA TOTO AIN’T IT FUN PARAMORE AIN’T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH GAYE & TERRELL AIN’T NO OTHER MAN CHRISTINA AGUILERA AIN’T NOBODY CHAKA KHAN AIN’T THAT A KICK IN THE HEAD DEAN MARTIN AMERICAN GIRL TOM PETTY ANOTHER ONE BITES THE DUST QUEEN ANY WAY YOU WANT IT JOURNEY ARE YOU GONNA BE MY GIRL JET AT LAST ETTA JAMES ATTENTION CHARLIE PLUTH BABY ONE MORE TIME BRITNEY SPEARS BACK IN LOVE AGAIN L.T.D. BEAT IT MICHAEL JACKSON BEST OF MY LOVE THE EMOTIONS BILLIE JEAN MICHAEL JACKSON BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BLURRED LINES ROBIN THICKE BOOGIE OOGIE OOGIE TASTE OF HONEY BORDERLINE MADONNA BORN TO BE WILD STEPPENWOLF BROKENHEARTED KARMIN CAKE BY THE OCEAN DNCE CALIFORNIA GIRLS KATY PERRY CALIFORNIA LOVE 2PAC CALL ME MAYBE CARLY RAE JEPSEN CALLING BATON ROUGE GARTH BROOKS CAN’T STOP THIS FEELING JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE CAR WASH ROLLS ROYCE CELEBRITY SKIN HOLE CLOSER CHAINSMOKERS COME OUT & PLAY OFFSPRING CRAZY IN LOVE BEYONCE DA YA THINK I’M SEXY STEWART & DNCE DANCE TO THE MUSIC SLY/FAMILY STONE DER KOMMISSAR AFTER THE FIRE DIE YOUNG KE$HA DON’T PHUNK WITH MY HEART BLACKEYED PEAS DON’T STOP BELIEVING JOURNEY DREAMS FLEETWOOD MAC ESCAPADE JANET JACKSON EVERYBODY BACKSTREET BOYS EVERYBODY WANTS YOU BILLY SQUIRE FAITHFULLY FAME DAVID BOWIE FEEL FOR YOU CHAKA KHAN FEELS CALVIN HARRIS FINALLY CECE PENISTON FINESSE BRUNO MARS FORGET YOU CEE LO GREEN GAME OF LOVE SANTANA GENIE IN A BOTTLE CHRISTINA AUGILERA GET DOWN ON IT KOOL & THE GANG GET INTO THE GROOVE MADONNA GET LUCKY DAFT PUNK GIRLS JUST WANNA HAVE FUN CINDI LAUPER GOOD VIBRATIONS MARKY MARK GOT TO BE REAL CHERYL LYNN GROOVE LINE HEATWAVE H.O.L.Y. -

That World of Somewhere in Between: the History of Cabaret and the Cabaret Songs of Richard Pearson Thomas, Volume I

That World of Somewhere In Between: The History of Cabaret and the Cabaret Songs of Richard Pearson Thomas, Volume I D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rebecca Mullins Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Dr. Scott McCoy, advisor Dr. Graeme Boone Professor Loretta Robinson Copyright by Rebecca Mullins 2013 Abstract Cabaret songs have become a delightful and popular addition to the art song recital, yet there is no concise definition in the lexicon of classical music to explain precisely what cabaret songs are; indeed, they exist, as composer Richard Pearson Thomas says, “in that world that’s somewhere in between” other genres. So what exactly makes a cabaret song a cabaret song? This document will explore the topic first by tracing historical antecedents to and the evolution of artistic cabaret from its inception in Paris at the end of the 19th century, subsequent flourish throughout Europe, and progression into the United States. This document then aims to provide a stylistic analysis to the first volume of the cabaret songs of American composer Richard Pearson Thomas. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to the person who has been most greatly impacted by its writing, however unknowingly—my son Jack. I hope you grow up to be as proud of your mom as she is of you, and remember that the things in life most worth having are the things for which we must work the hardest. -

Trevor Tolley Jazz Recording Collection

TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to collection ii Note on organization of 78rpm records iii Listing of recordings Tolley Collection 10 inch 78 rpm records 1 Tolley Collection 10 inch 33 rpm records 43 Tolley Collection 12 inch 78 rpm records 50 Tolley Collection 12 inch 33rpm LP records 54 Tolley Collection 7 inch 45 and 33rpm records 107 Tolley Collection 16 inch Radio Transcriptions 118 Tolley Collection Jazz CDs 119 Tolley Collection Test Pressings 139 Tolley Collection Non-Jazz LPs 142 TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION Trevor Tolley was a former Carleton professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1969 to 1974. He was also a serious jazz enthusiast and collector. Tolley has graciously bequeathed his entire collection of jazz records to Carleton University for faculty and students to appreciate and enjoy. The recordings represent 75 years of collecting, spanning the earliest jazz recordings to albums released in the 1970s. Born in Birmingham, England in 1927, his love for jazz began at the age of fourteen and from the age of seventeen he was publishing in many leading periodicals on the subject, such as Discography, Pickup, Jazz Monthly, The IAJRC Journal and Canada’s popular jazz magazine Coda. As well as having written various books on British poetry, he has also written two books on jazz: Discographical Essays (2009) and Codas: To a Life with Jazz (2013). Tolley was also president of the Montreal Vintage Music Society which also included Jacques Emond, whose vinyl collection is also housed in the Audio-Visual Resource Centre.