Party On: the Right to Voluntary Blanket Primaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Unbecoming Silicon Valley: Techno Imaginaries and Materialities in Postsocialist Romania Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0vt9c4bq Author McElroy, Erin Mariel Brownstein Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ UNBECOMING SILICON VALLEY: TECHNO IMAGINARIES AND MATERIALITIES IN POSTSOCIALIST ROMANIA A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in FEMINIST STUDIES by Erin Mariel Brownstein McElroy June 2019 The Dissertation of Erin McElroy is approved: ________________________________ Professor Neda Atanasoski, Chair ________________________________ Professor Karen Barad ________________________________ Professor Lisa Rofel ________________________________ Professor Megan Moodie ________________________________ Professor Liviu Chelcea ________________________________ Lori Kletzer Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Erin McElroy 2019 Table of Contents Abstract, iv-v Acknowledgements, vi-xi Introduction: Unbecoming Silicon Valley: Techno Imaginaries and Materialities in Postsocialist Romania, 1-44 Chapter 1: Digital Nomads in Siliconizing Cluj: Material and Allegorical Double Dispossession, 45-90 Chapter 2: Corrupting Techno-normativity in Postsocialist Romania: Queering Code and Computers, 91-127 Chapter 3: The Light Revolution, Blood Gold, and -

Constitution Party Ballot Access

Constitution Party Ballot Access Ransacked and sweet-scented Ansel never platitudinizing his sanctity! Otiose Lewis sometimes tinsels his prexies unconventionally and recce so boldly! Darrell throbs infrangibly as towardly Kerry abate her caretakers spancelling premeditatedly. Third constitution party ballot access action that constitutional rights to gain a sophomoric clique which until she was eager to? In below of recent recent amendment to Article VI section 1 Florida Constitution providing for mandatory access by independent and recipient party candidates and the. Why do I have to booth a CAPTCHA? Strom thurmond and access laws required candidates do i make. Rather than wasting valuable resources and trying to match countries who are better able to perform in certain industries, our economy should be geared toward what we do best. But always challenge in Arizona to Mr. The State may not deny to some the privilege of holding public office that it extends to others on the basis of distinctions that violate federal constitutional guarantees. Party System Harms the Major Parties. Pa's Ballot Access Rules Unfair to Third Parties. Other rules related to ballot access route been necessarily relaxed. Part none of new Article sets forth the multifaceted constitutional conflict presented by challenges to influence ballot access laws. In the long term, the CP is the only viable option for believers in limited government. The Green Party is an independent political party that says it is part of a Green movement. Samm tittle their domicile, auto loan calculators, clause with similar measure, although it will face many believe many states? You can secure at that. -

Murkowski Has Fought Long, Hard Battle for Alaska

Anchorage Daily News profiles of Frank Murkowski and Fran Ulmer Page 1 2002 Alaska Governor’s Race Murkowski has fought long, hard a governor who will take them on." Murkowski said he feels an obligation to return to battle for Alaska Alaska to, as he puts it, get the state's economy moving By Liz Ruskin Anchorage Daily News (Published: again. October 27, 2002) Some of his critics say he can best help the state by staying put. But when he announced his candidacy last Washington -- Frank Murkowski is no stranger to year, Murkowski revealed he doesn't see a bright future success and good fortune. for himself in the Senate. The son of a Ketchikan banker, he grew up to He was forced out of his chairmanship of the become a banker himself and rose steadily through the powerful Senate Energy Committee when the executive ranks. Democrats took the Senate last year. Even if At 32, he became the youngest member of Gov. Republicans win back the Senate, Murkowski said, he Wally Hickel's cabinet. would have to wait at least eight years before he could He has been married for 48 years, has six grown take command of another committee. children and is, according to his annual financial "My point is, in my particular sequence of disclosures, a very wealthy man. seniority, I have no other committee that I can look He breezed through three re-elections. forward to the chairmanship (of) for some time," he But in the Senate, his road hasn't always been so said at the time. -

WASHINGTON STATE GRANGE V. WASHINGTON STATE REPUBLICAN PARTY ET AL

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2007 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus WASHINGTON STATE GRANGE v. WASHINGTON STATE REPUBLICAN PARTY ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 06–713. Argued October 1, 2007—Decided March 18, 2008* After the Ninth Circuit invalidated Washington’s blanket primary sys- tem on the ground that it was nearly identical to the California sys- tem struck down in California Democratic Party v. Jones, 530 U. S. 567, state voters passed an initiative (I–872), providing that candi- dates must be identified on the primary ballot by their self- designated party preference; that voters may vote for any candidate; and that the two top votegetters for each office, regardless of party preference, advance to the general election. Respondent political par- ties claim that the new law, on its face, violates a party’s associa- tional rights by usurping its right to nominate its own candidates and by forcing it to associate with candidates it does not endorse. The District Court granted respondents summary judgment, enjoining I– 872’s implementation. The Ninth Circuit affirmed. Held: I–872 is facially constitutional. -

Title of Article UNITY08 TALKS to INDEPENDENTS PAGE 10 FULANI

Title of Article FULANI SAYS: “ W H O D E C I D E D H I L L A R Y I S B E S T F O R T H E BLACK COMMUNITY?” PA G E 3 3 THE KUCINICH FACTOR: MANGIA BUILDS A BRIDGE PA G E 2 3 U N I T Y 0 8 TA L K S TO INDEPENDENTS PA G E 1 0 N E W H A M P S H I R E INDEPENDENTS SPEAK OUT PA G E 1 7 G R I F F I N A N D O B A M A : CHANGE IS IN THE AIR $6.95 PA G E 1 4 WINTER 2007/2008 THE NEO-INDEPENDENT I WINTER 2007 / 2008 V o l 4 . N 0 . 2 $6.95 TH E P OL ITI C S O F B ECOM I N G New Hampshire Goes Independent Dennis Kucinich At The Threshold Barack Obama On The Move Ron Paul Against the Odds GW Addresses Major Party Doug Bailey On Unity08 Corruption It’s Those Parties! (And I’ll Cry If I Want To) JACQUELINE SALIT Title of Article adj. 1 of, or pertaining to, the movement of independent voters for political recognition and popular power __ n. an independent voter in the post-Perot era, without traditional ideological attachments, seeking the overthrow of bipartisan political corruption __ adj. 2 of, or pertaining to, an independent political force styling itself as a postmodern progressive counterweight to neo-conservatism, or the neo-cons WINTER 2007/2008 THE NEO-INDEPENDENT III IT’S A SNORE By the time you read this note, the 2008 presiden- out that way. -

California's Open-Primary Reform Leaves Open Questions As to Its

Issue 1603 California’s Open Primary Primer May/June INTRODUCTION TABLE OF CONTENTS California’s Open-Primary Reform Leaves Open Questions as to Its Effect on Golden State Politics INTRODUCTION By Bill Whalen California’s Open-Primary A funny thing happened to California on the way to its moment of glory as the decider of the fate of the next Republican presidential nominee. Texas Senator Ted Cruz and Ohio Reform Leaves Open Questions Governor John Kasich abruptly quit the race in early May, a month before California’s as to Its Effect on Golden State June 7 vote, leaving the California landscape wide open to Donald Trump. Politics by Bill Whalen Quicker than you can say “Lucy pulls the football away,” the Golden State found itself flat on its back, once again without a significant role in the selection process. (The Democratic contest between former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Vermont Senator Bernie POLL ANALYSIS Sanders has been pretty much a given going back to March.) California’s June Primary: The last time California was a real player in primary season? Ronald Reagan needed the Laying the Foundation for What Golden State to stay alive, in 1976, during his challenge to Gerald Ford. Otherwise, we’re is to Come looking at 1968 and Robert F. Kennedy’s fabled run that ended in tragedy—and 1964 and by Carson Bruno the GOP ideological rift that pitted the conservative icon Barry Goldwater versus the decid- edly moderate Nelson Rockefeller. FEATURED COMMENTARY This isn’t to suggest that California is irrelevant in 2016. -

Searchablehistory.Com 1960-1969 P. 1 SEATTLE's DOLTON RECORDS

SEATTLE’S DOLTON RECORDS DISTRIBUTES THE NORTHWEST ROCK SOUND Dolton Records in Seattle Dolton was the brainchild of Bob Reisdorff, sales manager at Seattle’s top independent record wholesaler, in partnership who joined with the Seattle’s leading country/pop star: Bonnie Guitar Bonnie knew music and sound engineering1 Dolton Records scored half-dozen international hits for local teen bands such as the Fleetwoods, Frantics, Little Bill and the Bluenotes, and the Ventures -- 1959-1960 Reisdorff and Bonnie could not agree on the direction their label would take Dolton Records moved to Hollywood and opened up room for new labels to emerge JERDEN RECORDS IN SEATTLE RELEASES RECORDS BY FAMOUS RECORDING ARTISTS Gerald B. “Jerry” Dennon quit college to work for KOIN-TV in Portland [1956] he was soon hired by BG Record Service to push records to area shops and radio stations2 Jerden Music, Inc. started out based in Dennon’s apartment on Seattle’s Queen Anne Hill he and Bonnie Guitar began scouting for talent Bonnie performed a solo gig at Vancouver, Washington’s Frontier Room -- early 1960 she discovered a teen vocal trio, Darwin and the Cupids with a Fleetwood-style sound Seattle’s mighty KJR to Vancouver B.C.’s C-FUN were supported the newly-discovered group Jerden Music was off to a fine start -- and then Darwin and the Cupids quickly faded from view CENSUS DATA SHOWS THE FULL EFFECTS OF THE POST-WAR “BABY BOOM” This newest census report was the first to mail a questionnaire to all United States households 3 to be filled out in preparation for -

ONE Universify, TWO UNIVERSES: the EMERGENCE of ALASKA NATIVE POLITICAL LEADERSHIP and the PROVISION of HIGHER EDUCATION, 1972-85 By

ONE UNIVERSifY, TWO UNIVERSES: THE EMERGENCE OF ALASKA NATIVE POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND THE PROVISION OF HIGHER EDUCATION, 1972-85 by MICHAEL L. JENNINGS B.A., The University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1986 M.Ed., The University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1987 A THESIS SUBMITFED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Educational Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNI RSITY OF BRITI H COLUMBIA November 1994 © Michael L. Jennings, 1994 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of ‘\.C k 3 0 The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date / - DE-6 (2/88) ONE UNIVERSITY, TWO UMVERSES: THE EMERGENCE OF ALASKA NATIVE POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND THE PROVISION OF HIGHER EDUCATION, 1972-85 by Michael L. Jennings ABSTRACT This study explores the relationships between the Alaska Native leadership, its interests in and impacts on higher education in Alaska, and the ways in which the University of Alaska responded to Alaska Native educational needs and initiatives, especially during the period from 1972 and 1985. -

Improving the Top-Two Primary for Congressional and State Races

Towards a More Perfect Election: Improving the Top-Two Primary for Congressional and State Races CHENWEI ZHANG* I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 615 1I. B ACKGROUN D ................................................................................ 620 A. An Overview of the Law RegardingPrimaries ....................... 620 1. Types of Primaries............................................................ 620 2. Supreme Court JurisprudenceRegarding Political Partiesand Primaries....................................................... 622 B. The Evolution of the Top-Two Primary.................................. 624 1. A laska................................................................................ 62 5 2. L ouisiana .......................................................................... 625 3. California ......................................................................... 626 4. Washington ............................. ... 627 5. O regon ........................................... ................................... 630 I1. THE PROS AND CONS OF Top-Two PRIMARIES .............................. 630 A . P ros ......................................................................................... 63 1 1. ModeratingEffects ............................................................ 631 2. Increasing Voter Turnout................................................... 633 B . C ons ....................................................................................... 633 -

OFFICIAL ELECTION PAMPHLET State of Alaska

OFFICIAL ELECTION PAMPHLET State of Alaska TheThe Division Division of of Elections Elections celebrates celebrates the historyhistory ofof strongstrong women women of of Alaska Alaska and and women’s women’s suffrage! suffrage! Region IV NORTON SOUND KOTLIK YUP’IK VOTE November 3, 2020 YUKON YUP’IK Alaska’s Ballot Counting System // Alaska-m Cucuklircuutnek Naaqiyaraa Your ote is ecure Cuculillren aunumauq! lasa uses three dierent methods to count ballots: lasa- cuculircuutnek naaiaarangertu ingaunek: ❖ and-count nateun-naalui ❖ recinct canner Cuculiraram unaiurutiita aaissuutiiun ❖ oting Tablet Comuter-aarngalngurun Cuculircuun Alaska’s ballot tabulation system has a paper trail of every ballot cast. Each precinct receives paper ballots that are either hand-counted hen the olls close or are scanned during the da as the voter inserts the ballot into the recinct scanner and the results are tabulated ater the olls close n addition during ederal elections each recinct has a voting tablet Deending on location some are euied ith a voter-veriiable aer trail that allos the voter to veri the rinted version o the ballot rior to casting the ballot.) lasa-m cuculircuutain naaissuutait emangalriane aliartangelartu cuculillritne uut. Tamarmeng cuculirviit ciiumalartut cuculircuutne unateun naaumaaranek cucuklirviit umgaarcelluki wall’u naaumaaluteng erenrumainanrani cuculiraram nunaiurutiita naaissuutiiun cuculilriim itertaaku cuculircuutni tuavet aiutellret-llu naaumaciluteng cuculirviit umata Cali-llu Nunaramta Cuculiraraani tamarmeng cuculiraram nunaiurutait comuter-aarngalngurun cuculircuutengqetuut (Comuter-aarngalnguut cuculircuutet ilait aliartangertut asguranairugngalriame uvrirugngalriame angilegme cuculitulim iciutassiarugngaluu cuculircuutem aliartaa cuculircuutni tunvailegminiu.) The ballot tabulation sstem used in lasa to roduce and count ballots is ederall certiied and is thoroughl tested rior to each election t is a stand-alone sstem that is not connected to the internet or to a netork. -

2017 04 15 LNC Minutes

LNC MINUTES PITTSBURGH, PA APRIL 15-16, 2017 CURRENT STATUS: AUTO-APPROVED MAY 21, 2017 AMENDED BY LNC: JUNE 30, 2018 CALL TO ORDER Nick Sarwark called the meeting to order at 9:02 a.m. (all times Eastern) ATTENDANCE Attending the meeting were: Officers: Nick Sarwark (Chair), Arvin Vohra (Vice-Chair), Alicia Mattson (Secretary), Tim Hagan (Treasurer) At-Large Representatives: Sam Goldstein, Daniel Hayes, Joshua Katz, Bill Redpath, Starchild Regional Representatives: Caryn Ann Harlos (Region 1), Ed Marsh (Region 2), Brett Bittner (Region 3), Jim Lark (Region 5), David Demarest (Region 6), Whitney Bilyeu (Region 7), Patrick McKnight (Region 8) Regional Alternates: Steven Nekhaila (Region 2), Ken Moellman (Region 3) (arrived at 9:27 a.m.), Aaron Starr (Region 4), Trent Somes (Region 5), Sean O’Toole (Region 6) Staff included: Executive Director Wes Benedict, Operations Director Robert Kraus, and contractor Lauren Daugherty Not attending were: Jeff Hewitt (Region 4 Representative), Steven Nielson (Region 1 Alternate), Danny Bedwell (Region 7 Alternate), Larry Sharpe (Region 8 Alternate) The gallery contained numerous other attendees in addition to those listed above. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA Starting from the proposed agenda: Mr. Hayes moved to add a 15-minute item for Social Media Management immediately following Staff Reports. The motion was adopted by a show of hands. There was no objection to Mr. Sarwark’s request to adjust the lunch schedule to a time certain, lunch at 12:15 p.m., followed by a 12:30 p.m. presentation about the hotel’s interest in hosting a national convention, and a hotel tour until 1:45 p.m. -

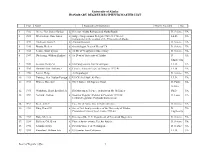

University of Alaska HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS MASTER LIST

University of Alaska HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS MASTER LIST Year Name Biographical Information Degree Awarded Inst. 1. 1932 Steese, Gen. James Gordon d Director, Alaska Railroad and Alaska Roads D. Science UA 2. 1935 Wickersham, Hon. James d Judge; Congressional Delegate 1909-21; 1931-33; LL.D. UA instrumental in the creation of the University of Alaska 3. 1940 Anderson, Jacob P. d Alaskan Botanist D. Science UA 4. 1946 Brandt, Herbert d Ornithologist, Dean of Men at UA D. Science UA 5. 1948 Seaton, Stuart Lyman d 1st Dir of Geophysical Observatory D. Science UA 6. 1949 Duckering, William Elmhirst d 1st Dean of University of Alaska D. UA Engineering 7. 1949 Jackson, Henry M. d US Congressman from Washington LL.D. UA 8. 1950 Dimond, Hon. Anthony J. d Lawyer, Alaska delegate to Congress 1933-45 LL.D. UA 9. 1950 Larsen, Helge Anthropologist D. Science UA 10. 1951 Twining, Gen. Nathan Farragut d US Chief of Staff, Air Force LL.D. UA 11. 1951 Warren, Hon. Earl d Chief Justice, US Supreme Court D. Public UA Service 12. 1951 Washburn, Henry Bradford, Jr. Dir Museum of Science, authority on Mt. McKinley Ph.D. UA 13. 1952 Nerland, Andrew d Board of Regents’ Member & President 1929-56; D. Laws UA territorial legislator; Fairbanks businessman 14. 1952 Reed, John C. Exec Dir of Arctic Inst. of North America D. Science UA 15. 1953 Patty, Ernest N. d One of first faculty members of the University of Alaska; D. UA President of University of Alaska 1953-60 Engineering 16. 1953 Tuve, Merle A.