18 September 1982 to 18 March 1983

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

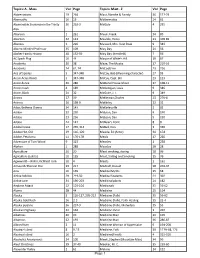

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Latitude 38'S Guide to Bay Sailing

MayCoverTemplate 4/21/09 9:51 AM Page 1 Latitude 38 VOLUME 383 May 2009 WE GO WHERE THE WIND BLOWS MAY 2009 VOLUME 383 BAYGUIDE SAILING TO BAY SAILINGGUIDE Is there anyone out there who's worth of learning the hard way into one and is worth a pass. Stay in the channel not feeling the pinch of the recession? grand tour of the Bay done in style and though, as the northeast side is shallow We doubt it. And yes, many are feeling comfort. We call it the The Perfect Day- and the bottom is riddled with debris. more than a pinch. We're reminded of sail, and it goes like this... Sailing back out the Sausalito Chan- the advice of Thomas Jefferson: "When Start anywhere east of Alcatraz about nel, hug the shoreline and enjoy the you get to the end of your rope, tie a 11 a.m., at which time the fog is begin- Mediterranean look of southern Sau- knot and hang on!" ning to burn off and a light breeze is fill- salito. Generally, the closer you stay to Speaking of ropes and knots and ing in. You're going to be sailing coun- this shore, the flukier the wind — until hanging on, while the 'suits' rage from terclockwise around the Bay, so from you get to Hurricane Gulch. It's not shore while the economy struggles to Alcatraz, head around the backside of marked on the charts, but you'll know extricate itself from the tarpit — we Angel Island and sail west up Raccoon when you're there. -

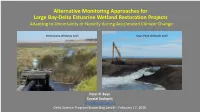

Alternative Monitoring Approaches for Large Bay-Delta Estuarine Wetland Restoration Projects Adapting to Uncertainty Or Novelty During Accelerated Climate Change

Alternative Monitoring Approaches for Large Bay-Delta Estuarine Wetland Restoration Projects Adapting to Uncertainty or Novelty during Accelerated Climate Change Montezuma Wetlands 2015 Sears Point Wetlands 2015 Peter R. Baye Coastal Ecologist [email protected] Delta Science Program Brown Bag Lunch – February 17, 2016 Estuarine Wetland Restoration San Francisco Bay Area historical context ERA CONTEXT “First-generation” SFE marsh restoration • Regulatory permit & policy (CWA, (1970s-1980s) McAteer-Petris Act, Endangered Species Act • compensatory mitigation • USACE dredge material marsh creation national program; estuarine sediment surplus “Second-generation” SFE marsh restoration • Goals Project era transition to regional planning and larger scale restoration • Wetland policy conflict resolution • Geomorphic pattern & process emphasis 21st century SFE marsh restoration • BEHGU (Goals Project update) era: • Accelerated sea level rise • Estuarine sediment deficit • Climate event extremes, species invasions as “new normal” • advances in wetland sciences Estuarine Wetland Restoration San Francisco Bay Area examples ERA EXAMPLES First-generation SFE marsh restoration • Muzzi Marsh (MRN) (1970s-1980s) • Pond 3 Alameda (ALA) Second-generation SFE marsh restoration • Sonoma Baylands (SON) (1990s) • Hamilton Wetland Restoration (MRN) • Montezuma Wetlands (SOL) 21st century SFE marsh restoration • Sears Point (SON) (climate change) • Aramburu Island (MRN) • Cullinan Ranch (SOL) • Oro Loma Ecotone (“horizontal levee”) (ALA) • South Bay and Napa-Sonoma -

Aramburu Island Shoreline Protection and Ecological Enhancement Project Draft Enhancement Plan

Wetlands and Water Resources, Inc. 818 Fifth Avenue, Suite 208 San Rafael, CA 94901 Tel 415.457.0250 Fax 415.457.0260 www.swampthing . org Aramburu Island Shoreline Protection and Ecological Enhancement Project Draft Enhancement Plan April 19, 2010 Prepared for: Richardson Bay Audubon Sanctuary 376 Greenwood Beach Road Tiburon, CA 94920 In Partnership with: Marin County Department of Parks and Open Space 3501 Civic Center Drive, Room 260 San Rafael, CA 94903 Project No. 1145 Prepared in Collaboration with: Roger Leventhal, PE, FarWest Restoration Engineering Peter Baye, PhD Planning Assessment Design Implementation Applied Science This page intentionally left blank Aramburu Island Shoreline Protection and Ecological Enhancement Project Draft Enhancement Plan 19 April 2010 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2 SITE DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 HISTORY OF RICHARDSON BAY ................................................................................................................................ 3 2.2 HISTORY OF ARAMBURU ISLAND AND HARBOR SEAL HAUL‐OUT .................................................................................... 3 2.3 SURROUNDING LAND USES AND HABITATS ............................................................................................................... -

'Richardson 'Ba:Y Ijjocf and 'Boat Stud:Y

'Richardson 'Ba:y IJJocf and'Boat Stud:y The Cumulative Effects of Dock Development and Boat Traffic on Wildlife and the Richardson Bay Wildlife Sanctuary Adopted by the Marin County Board of Supervisors on October 31, 2000. Prepared for The County of Marin by Greg R. Zitney Zitney & Associates October 2000 Richardson Bay Dock and Boat Study FOREWORD This report has been prepared pursuant to a contract with the County of Marin by Greg R. Zitney of Zitney & Associates. Conclusions and recommendations presented in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent official County position or policy with regard to the topics addressed. Staff of the Marin County Community Development Agency contributed to this study by completing the inventory of existing and potential dock sites, preparing maps for the report, and reviewing report drafts. The Study is intended to be used as an informational document which focuses on the potential for biological and cumulative impacts from the buildout of dock facilities in the study area. The recommendations contained in the Study are intended to be advisory in nature and do not extinguish, make non-conforming, or eliminate any property owner's legal rights to construct new boat docks, to rebuild pre-existing dock facilities, or to use and enjoy navigational easements. Recommendations contained in this report are applicable only to the extent that they are within the jurisdictional authority of the County of Marin. The recommendations contained in the Study are intended to be advisory to the towns of Tiburon and Belvedere to the extent portions of the study area are also located within their respective jurisdictions. -

SFBJV Active Projects, November 2019 Page 1

SFBJV Active Projects, November 2019 Project Funding Needs Project Name County Description Acres Lead Rank 3-5 yr Alameda Creek Diversion Dam This project will reduce water diversions and construct a fish Alameda Creek Tier 1 Alameda NA $0 Fish Passage ladder and fish screens on the Alameda Diversion Dam. Alliance This project aims to restore a run of steelhead trout to Alameda Alameda Creek Fisheries Creek. Removal of barriers, improved flows, and other Alameda Creek Tier 1 Alameda NA $12,000,000 Restoration improvements will help support steelhead spawning and Alliance rearing and ultimately restore steelhead fisheries. This project will design and install a fish ladder on the northern Alameda County embankment of the flood control channel and Alameda County Alameda Creek Upper Rubber Water District, Tier 1 Alameda Water District's Rubber Dam No. 3. The fish ladder will help 0.1 $0 Dam No. 3 Fish Ladder Alameda Creek facilitate fish migration through the lower section of Alameda Alliance Creek. The East Bay Regional Park District is converting the former Naval Air Station for use as wildlife habitat and public East Bay Regional Alameda Point Restoration Tier 1 Alameda 660 $0 parkland. This project will extend access to restored shoreline Park District areas and will help support an endangered least tern colony. The project enhanced Albany Beach by arresting beach erosion and expanding dune and wetlands, and constructed wetland Albany Beach Restoration and and rain garden features to improve water quality. Current East Bay Regional Public Access Project - Tier 1 Alameda 3 $4,000,000 work includes completing a key segment of the SF Bay Trail, Park District McLaughlin Eastshore State Park expanding public shoreline access, and constructing visitor amenities. -

Lesson 1 18 Focus Question What and Where Is Angel Island

ANGEL ISLAND IMMIGRATION JOURNEYS Lesson 1 LESSON 1: WHERE IS ANGEL ISLAND? AN INTRODUCTORY GEOGRAPHY LESSON Focus Question What and where is Angel Island? Objective Students will reflect on their previous knowledge of immigration. Students will identify the location of Angel Island and its Immigration Station, and create a map with its relation to other geographic features in the San Francisco Bay area. Grades 4 - 8 Time 45 to 50 minute period, plus homework Materials Copies of historical photograph of immigrants arriving at Angel Island to individual students or small groups of students, or Xerox photo on to an overhead transparency and project with an overhead projector on to a wall or screen, Maps such as a map of the United States, San Francisco maps, Angel Island maps, road atlases, Angel Island and California State Parks materials or websites (if a classroom computer is available to the students). Student work sheet with instructions Blank outline map Fine-tip black pens Colored pencils Standards California History-Social Science Standards (See Standards Connections section) Procedure Introduction to Immigration 1. Have students look at photograph of immigrants arriving at Angel Island but passing out photocopies or by projecting the image from an overhead transparency of the photo enlarged on the overhead projector on to a screen or blank wall. 2. Write on the board, the introductory journal entry for the day: “Why might people move from one place to another? Define the word “immigration,” and tell what you know about it.” 3. Have students spend about ten minutes writing on these topics. Have class share ideas. -

Aramburu Island Shoreline Protection and Ecological Enhancement Project Draft Enhancement Plan

Wetlands and Water Resources, Inc. 818 Fifth Avenue, Suite 208 San Rafael, CA 94901 Tel 415.457.0250 Fax 415.457.0260 www.swampthing . org Aramburu Island Shoreline Protection and Ecological Enhancement Project Draft Enhancement Plan April 19, 2010 Prepared for: Richardson Bay Audubon Sanctuary 376 Greenwood Beach Road Tiburon, CA 94920 In Partnership with: Marin County Department of Parks and Open Space 3501 Civic Center Drive, Room 260 San Rafael, CA 94903 Project No. 1145 Prepared in Collaboration with: Roger Leventhal, PE, FarWest Restoration Engineering Peter Baye, PhD Planning Assessment Design Implementation Applied Science This page intentionally left blank Aramburu Island Shoreline Protection and Ecological Enhancement Project Draft Enhancement Plan 19 April 2010 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2 SITE DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 HISTORY OF RICHARDSON BAY ................................................................................................................................ 3 2.2 HISTORY OF ARAMBURU ISLAND AND HARBOR SEAL HAUL‐OUT .................................................................................... 3 2.3 SURROUNDING LAND USES AND HABITATS ............................................................................................................... -

Cosco Busan Oil Spill NRDAR Focus on Aramburu: the Little Island That Could

Cosco Busan Oil Spill NRDAR Focus on Aramburu: The Little Island that Could Janet Whitlock, Toby McBride, - USFWS Rachel Spadafore – Richardson Bay Audubon Center and Sanctuary San Francisco Bay • Largest Estuary on the Pacific Coast of North America • Western Hemispheric Shorebird Reserve Network Highest possible ranking – Home to close to 1 million shorebirds • Center for Biological Diversity: Nation’s 6 most important bio- diversity hotspots – Over 500 species of invertebrates and 500 species of vertebrates • Diverse and rich shoreline habitat for shorebirds, waterfowl, fish, and other species Cosco Busan Oil Spill • November 7, 2007 – Cosco Busan container ship strikes San Francisco Bay Bridge – Releases 53,500+ gallons of Fuel Oil – 3,000 birds collected, over 100 miles of shoreline oiled Cosco Busan Oil Spill Golden Gate San Francisco Collision • Majority of impacts in the Central Bay • Oiling along outer coast from Pt Reyes in the north to Half-Moon Bay in the south Beach Disturbance and Wrack Removal Hot Water Washing Kirby Cove Albany Angel Island Stege Marsh Manual Cleaning and Vegetation Cutting Trampling and Removal NRDA Injuries • 6,800 birds estimated dead: 65 species – Primarily Diving ducks (Scaup and Scoter) – Cormorants, Common Murres, Grebes – T&E species - Snowy Plover and Marbled Murrelets also impacted • Estimated up to ~25% of 2007-08 herring spawn lost due to egg mortality from oil exposure • 3,300+ acres of shoreline habitat impacted • Over 1 million user days of human recreational uses (surfing, recreational fishing, beach use etc.) NRDA Restoration: $32.3 million • Lost Human Uses: $18.8 Million • Herring : $2.5 Million • Birds: $5 Million • Shoreline Habitats: $4 Million • T.C. -

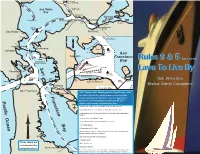

Rule 9 & 5, Laws to Live By

Petaluma River Mare Island Bridge Causeway Bridge Petaluma River Mar e I. Str Vallejo San Pablo ait Channel Bay eet Mare I. Carquinez thball Fl Bridge Mo Dillon Suisun Channel Carqu Pt. Selby inez Bay Pumphouse Davis Pt. Strait Benicia Rodeo Port nole Shoal Crockett Pi Chicago Avon "E"cho Benicia-Martinez Bridge Buoy Pt. Pinole San Rafael Martinez McNears Pt. San Pedro Bluff Pt. Southampton Shoal Channel Pt. San Pablo rait Pt. Simpton Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Richmond Raccoon StAngel I. "A"lpha Larkspur Buoy Red Pt. Knox Rock Long Wharf Pt. Blunt San Sausalito Francisco Rules 9 & 5 ....... Southampton Bay r Shoal Channel Harding e Tiburon t Rock Buoy San Alcatraz I. Deep Wate Westbound Lane Angel I. Traffic Lan Treasure I. Laws To Live By Sausalito Raccoon Strai astbound Lane Berkeley Pier E Blossom Golden Rock Buoy Gate Presidio Shoal Bridge Alcatraz I. Golden Yerba Buena I. Treasure I. Bay Gate San Francisco Bridge Bridge Bay Pt. Bonita San Francisco Bridge Harbor Safety Committee Mile Oakland Rock Central Bay San Francisco Alameda The Captain of the Port designates the following areas (in white) where deep draft commercial and public Francisco vessels routinely operate to be "narrow channels or Pacific Ocean fairways", for the purpose of enforcing RULE 9 (please refter to map for location of sites). OAK • Golden Gate Traffic Lanes and Golden Gate Precautionary Area Hunter's • Central Bay Traffic Lanes and Central Bay Precautionary Area Point • Oakland Harbor Bar Channel and Oakland Outer Harbor and Oakland Inner Harbor San Bruno Shoal • Alameda Naval Air Station Channel • So. -

Deer Discussion Attachment 1 to City Council Staff Report

DEER - ATTACHMENT 1 DEER DISCUSSION ATTACHMENT 1 TO CITY COUNCIL STAFF REPORT STAFF REPORT AND MEMO FROM DEER COMMITTEE NOVEMBER 2009 REPORTS BELVEDERE CITY COUNCIL NOVEMBER 9, 2009 To: Mayor and City Council From: Felicia N. Wheaton, Associate Planner Subject: Findings and recommendations of Deer Committee Recommended Motion/Item Description Review and discuss the findings of the Deer Committee and provide staff with direction with respect to the specific recommendations of the Committee. Background Black-tailed deer are a common sight in Belvedere, particularly on the Island. The deer feed on a variety of plants, traverse well-worn paths, and bed in pockets of dense vegetation. The total number of deer on the Island is unknown, although there is quantity enough to cause aggravation among many of our residents. The City received enough communications expressing concern about the deer to warrant the formation of a citizen committee to research the issues and investigate potential solutions. The Deer Committee held seven public meetings from February to September of 2009. A community-wide questionnaire was conducted to gauge local concern about the issue. The questionnaire had an impressive 50 percent response rate. The majority of respondents resided on the Island and wished for more effort toward deer population control. Concerns ranged from yard damage to fear of personal injury. A summary of the questionnaire results is included in the City of Belvedere Deer Study (Attachment 3). Findings Representatives from the State Department of Fish and Game (DFG) advised the Deer Committee that the deer were a State resource that could not be proactively addressed without the advice and consent of DFG. -

1973 Strawberry Community Plan

THE STRAWBERRY COMMUNITY PLAN November 5, 1973 This text, with rev1s1ons and corrections and accompanying maps was recommended .for. adoption by the Marin County Planning Commission on January 14, 1974 and adopted by the Marin County Board of Supervisors on August 27, 1974 by Resolution No. 74-269. Published by Marin County Planning Department Civic Center San Rafael, California 94903 CREDITS Strawberry Area Community Council Chairman Stanley Gallagher Committee Coordinator Sandra Dorsaneo Citizen Committees Members Open Space Martin Rosse Elizabeth Doss Grace Vaghti Estelle Radovich Darrell Meyer Edith Wi 11 ett John Lochridge Richard May Craig Dorsey Dennis Klein Monique Israel Connie Diernisse Kent Baldwin Public Facilities John Long Doug De La Fontaine Doug Radovich Residential & Commercial Ed Sotelo G. Allard Land Use Martin Rosse Laurie Jadot Estel Carte Trudy De La Fontaine Kris Zealear Edith Wi 11 ett Paul Hecht John Radovich Margaret O'Brien Schools Kate Supinski Transportation Kent Baldwin Kris Zealear Al Stillman Lillian & Earl Koski Ralph Phi 11 ips County Staff Werner von Gundell, Planning Director Sol Silver, Chief, Advance Planning Harvey Bragdon, Chief, Current Planning Ellis Gans,-Principal Planner, Advance Planning Alice Grissom, Secretary, Advance Planning Consultant and staff member responsible for this plan - Steven E. Chaum PLAN DISTRIBUTION LIST The long form of this plan was distributed to the following groups or agencies together with a proposed land use map. Display maps illustrating the various elements of the plan are available for viewing at the Marin County Planning Department. Additional copies of this plan will be provided for a duplication charge given a on~ w~ek notice.