The Mysteries of Bird Migration – Still Much to Be Learnt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of Anchorage Checklist

ACCIDENTAL, CASUAL, UNSUBSTANTIATED KEY THRUSHES J F M A M J J A S O N D n Casual: Occasionally seen, but not every year Northern Wheatear N n Accidental: Only one or two ever seen here Townsend’s Solitaire N X Unsubstantiated: no photographic or sample evidence to support sighting Gray-cheeked Thrush N W Listed on the Audubon Alaska WatchList of declining or threatened species Birds of Swainson’s Thrush N Hermit Thrush N Spring: March 16–May 31, Summer: June 1–July 31, American Robin N Fall: August 1–November 30, Winter: December 1–March 15 Anchorage, Alaska Varied Thrush N W STARLINGS SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER SPECIES SPECIES SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER European Starling N CHECKLIST Ross's Goose Vaux's Swift PIPITS Emperor Goose W Anna's Hummingbird The Anchorage area offers a surprising American Pipit N Cinnamon Teal Costa's Hummingbird Tufted Duck Red-breasted Sapsucker WAXWINGS diversity of habitat from tidal mudflats along Steller's Eider W Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Bohemian Waxwing N Common Eider W Willow Flycatcher the coast to alpine habitat in the Chugach BUNTINGS Ruddy Duck Least Flycatcher John Schoen Lapland Longspur Pied-billed Grebe Hammond's Flycatcher Mountains bordering the city. Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel Eastern Kingbird BOHEMIAN WAXWING Snow Bunting N Leach's Storm-Petrel Western Kingbird WARBLERS Pelagic Cormorant Brown Shrike Red-faced Cormorant W Cassin's Vireo Northern Waterthrush N For more information on Alaska bird festivals Orange-crowned Warbler N Great Egret Warbling Vireo Swainson's Hawk Red-eyed Vireo and birding maps for Anchorage, Fairbanks, Yellow Warbler N American Coot Purple Martin and Kodiak, contact Audubon Alaska at Blackpoll Warbler N W Sora Pacific Wren www.AudubonAlaska.org or 907-276-7034. -

Technical Assistance Layout with Instructions

Biodiversity Action Plan Project Number: 51257-001 August 2019 GEO: North–South Corridor (Kvesheti–Kobi) Road Project Prepared by Earth Active and DG Consulting Ltd. for the Asian Development Bank. This report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. KVESHETI – KOBI ROAD NORTH SOUTH HIGHWAY, GEORGIA BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN Kvesheti – Kobi Road Upgrade Biodiversity Action Plan EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document provides the Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) for the proposed Kvesheti to Kobi Road Upgrade Project. It is informed by, and should be read alongside, the Project Critical Habitat Assessment (CHA). The CHA has identified potential areas of Critical Habitat (CH) and Priority Biodiversity Features (PBF) that require special protection or mitigation to ensure that the Project achieves “no net conservation loss” or “net conservation gain” as appropriate. The Project is part of a program launched by the Government of Georgia (GoG) and the Roads Department to upgrade the major roads of the country. The road between Kvesheti and Kobi currently runs for some 35km and is at times impassable in the winter months, whilst also having a poor safety record. -

Bird Flu Research at the Center for Tropical Research by John Pollinger, CTR Associate Director

Center for Tropical Research October 2006 Bird Flu Research at the Center for Tropical Research by John Pollinger, CTR Associate Director Avian Influenza Virus – An Overview The UCLA Center for Tropical Research (CTR) is at the forefront of research and surveillance efforts on avian influenza virus (bird flu or avian flu) in wild birds. CTR has led avian influenza survey efforts on migratory landbirds in both North America and Central Africa since spring 2006. We have recently been funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to conduct a large study in North, Central, and South America on the effects of bird migration and human habitat disturbance on the distribution and transmission of bird flu. These studies take advantage of our unique collaboration with the major bird banding station networks in the Americas, our extensive experience in avian field research in Central Africa, and UCLA’s unique resources and expertise in infectious diseases though the UCLA School of Public Health and its Department of Epidemiology. CTR has ongoing collaborations with four landbird monitoring networks: the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) network, the Monitoring Avian Winter Survival (MAWS) network, and the Monitoreo de Sobrevivencia Invernal - Monitoring Overwintering Survival (MoSI) network, all led by the Institute for Bird Populations (IBP), and the Landbird Migration Monitoring Network of the Americas (LaMMNA), led by the Redwood Sciences Laboratory (U.S. Forest Service). Bird flu has shot to the public’s consciousness with the recent outbreaks of a highly virulent subtype of avian influenza A virus (H5N1) that has recently occurred in Asia, Africa, and Europe. -

A Bird's EYE View on Flyways

A BIRD’S EYE VIEW ON FLywayS A brief tour by the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals IMPRINT Published by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Secretariat of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) A BIRD’S EYE VIEW ON FLywayS A brief tour by the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals UNEP / CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany. 68 pages. Produced by UNEP/CMS Text based on a report by Joost Brouwer in colaboration with Gerard Boere Coordinator Francisco Rilla, CMS Secretariat, E-mail: [email protected] Editing & Proof Reading Hanah Al-Samaraie, Robert Vagg Editing Assistant Stéphanie de Pury Publishing Manager Hanah Al-Samaraie, Email: [email protected] Design Karina Waedt © 2009 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) / Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. DISCLAIMER The contents of this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of UNEP or contributory organizations.The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or contrib- utory organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area in its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Partial Migration in the Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates Pelagicus Melitensis

Lago et al.: Partial migration in Mediterranean Storm Petrel 105 PARTIAL MIGRATION IN THE MEDITERRANEAN STORM PETREL HYDROBATES PELAGICUS MELITENSIS PAULO LAGO*, MARTIN AUSTAD & BENJAMIN METZGER BirdLife Malta, 57/28 Triq Abate Rigord, Ta’ Xbiex XBX 1120, Malta *([email protected]) Received 27 November 2018, accepted 05 February 2019 ABSTRACT LAGO, P., AUSTAD, M. & METZGER, B. 2019. Partial migration in the Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis. Marine Ornithology 47: 105–113. Studying the migration routes and wintering areas of seabirds is crucial to understanding their ecology and to inform conservation efforts. Here we present results of a tracking study carried out on the little-known Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis. During the 2016 breeding season, Global Location Sensor (GLS) tags were deployed on birds at the largest Mediterranean colony: the islet of Filfla in the Maltese Archipelago. The devices were retrieved the following season, revealing hitherto unknown movements and wintering areas of this species. Most individuals remained in the Mediterranean throughout the year, with birds shifting westwards or remaining in the central Mediterranean during winter. However, one bird left the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar and wintered in the North Atlantic. Our results from GLS tracking, which are supported by data from ringed and recovered birds, point toward a system of partial migration with high inter-individual variation. This highlights the importance of trans-boundary marine protection for the conservation of vulnerable seabirds. Key words: Procellariformes, movement, geolocation, wintering, Malta, capture-mark-recovery INTRODUCTION The Mediterranean Storm Petrel has been described as sedentary, because birds are present in their breeding areas throughout the year The Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis is (Zotier et al. -

(2007): Birds of the Aleutian Islands, Alaska Please

Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi OSPREYS FINCHES Osprey Ca Ca Ac Brambling I Ca Ca EAGLES and HAWKS Hawfinch I Ca Northern Harrier I I I Common Rosefinch Ca Eurasian Sparrowhawk Ac (Ac) Pine Grosbeak Ca Bald Eagle* C C C C Asian Rosy-Finch Ac Rough-legged Hawk Ac Ca Ca Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch* C C C C OWLS (griseonucha) Snowy Owl I Ca I I Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch (littoralis) Ac Short-eared Owl* R R R U Oriental Greenfinch Ca FALCONS Common Redpoll I Ca I I Eurasian Kestrel Ac Ac Hoary Redpoll Ca Ac Ca Ca Merlin Ca I Red Crossbill Ac Gyrfalcon* R R R R White-winged Crossbill Ac Peregrine Falcon* (pealei) U U C U Pine Siskin I Ac I SHRIKES LONGSPURS and SNOW BUNTINGS Northern Shrike Ca Ca Ca Lapland Longspur* Ac-C C C-Ac Ac CROWS and JAYS Snow Bunting* C C C C Common Raven* C C C C McKay's Bunting Ca Ac LARKS EMBERIZIDS Sky Lark Ca Ac Rustic Bunting Ca Ca SWALLOWS American Tree Sparrow Ac Tree Swallow Ca Ca Ac Savannah Sparrow Ca Ca Ca Bank Swallow Ac Ca Ca Song Sparrow* C C C C Cliff Swallow Ca Golden-crowned Sparrow Ac Ac Barn Swallow Ca Dark-eyed Junco Ac WRENS BLACKBIRDS Pacific Wren* C C C U Rusty Blackbird Ac LEAF WARBLERS WOOD-WARBLERS Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Wood Warbler Ac Yellow Warbler Ac Dusky Warbler Ac Blackpoll Warbler Ac DUCKS, GEESE and SWANS Kamchatka Leaf Warbler Ac Yellow-rumped Warbler Ac Emperor Goose C-I Ca I-C C OLD WORLD FLYCATCHERS "HYPOTHETICAL" species needing more documentation Snow Goose Ac Ac Gray-streaked Flycatcher Ca American Golden-plover (Ac) Greater White-fronted Goose I -

CMS/CAF/Inf.4.13 1 Central Asian Flyway Action Plan for Waterbirds and Their Habitat Country Report

CMS/CAF/Inf.4.13 Central Asian Flyway Action Plan for Waterbirds and their Habitat Country Report - INDIA A. Introduction India situated north of the equator covering an area of about 3,287,263 km2 is one of the largest country in the Asian region. With 10 distinctly different bio geographical zones and many different habitat types, the country is known amongst the top 12 mega biodiversity countries. India is known to support 1225 species of bird species, out of these 257 species are water birds. India remains in the core central region of the Central Asian Flyway (CAF) and holds some crucial important wintering population of water bird species. India is also a key breeding area for many other water birds such as Pygmy cormorant and Ruddy-shelduck, globally threatened water birds such as Dalmatian Pelican, Lesser White-fronted Goose, Siberian crane, oriental white stork, greater adjutant stork, white winged wood duck etc. Being located in the core of the CAF, and several important migration routes the country covers a large intra-continental territory between Arctic and Indian Ocean. Being aware of the importance of the wetlands within the geographic boundary of the India for migrating avifauna, India has developed a wetland conservation programme. India currently has 19 RAMSAR sites. India has identified more than 300 sites which has the potential to be consider as the RAMSAR sites. However, being the second most populus nation in the world with agricultural economy, wetlands are one of the most used habitat with water bird and human interface. Much of the Indian landmass also being dependent to the normal monsoonal rainfall for precipitation is also subjected to extremes of drought and flood making the wetlands vulnerable to drastic ecological changes. -

Spring Migration Phenology of Wheatear Species in Southern Turkey

Original research Spring migration phenology of wheatear species in Southern Turkey Hakan KARAARDIÇ1,*, , Ali ERDOĞAN2, 1Department of Math and Science Education, Education Faculty, Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat University, Alanya, Antalya, Turkey. 2Department of Biology, Science Faculty, Akdeniz University, Antalya, Turkey *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Millions of birds migrate between breeding and wintering areas every year. Turkey has many important areas for migratory birds as stopover or wintering. The coastal line of the southern Turkey provides safety resting areas and rich opportunity for refueling. Boğazkent is one of the important area just coast line of the Mediterranean Sea and we studied the migration phenology and stopover durations of three Wheatear species: Northern wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe), Isabelline wheatear (Oenanthe isabellina) and Black-eared wheatear (Oenanthe hispanica). Addition to these species, Desert wheatear (Oenanthe deserti) and Finsch’s wheatear (Oenanthe finschii) also were captured in the study. Birds were captured by using spring traps baited with mealworms, Tenebrio molitor, throughout the daylight period from the 1st of March to the 31st May both in 2009 and 2010. More northern wheatears use this site to stopover. It was determined that the spring migration of the Northern wheatear at study site takes two months, whereas Isabelline and Black-eared wheatears have almost one-month migrations in southern Turkey after passing the Mediterranean Sea. On the other hand, timing of spring migration has differences between wheatear species. Keywords: Ecological barrier, Migration, Oenanthe spp., Phenology, Turkey, Wheatears Citing: Karaardiç, H., & Erdoğan, A. (2019). Spring migration phenology of wheatear species in Southern Turkey. Acta Biologica Turcica, 32(2): 65-69. -

Hitchhikers' Guide to Analysing Bird Ringing Data

Ornis Hungarica 2015. 23(2): 163–188. DOI: 10.1515/orhu-2015-0018 Hitchhikers’ guide to analysing bird ringing data Part 1: data cleaning, preparation and exploratory analyses ANDREA HARNOS1*, PÉTER FEHÉRVÁRI2 & Tibor Csörgő3 Andrea Harnos, Péter Fehérvári & Tibor Csörgő 2015. Hitchhikers’ guide to analysing bird ring- ing data – Part 1. – Ornis Hungarica 23(2): 163–188. Abstract Bird ringing datasets constitute possibly the largest source of temporal and spatial in- formation on vertebrate taxa available on the globe. Initially, the method was invented to un- derstand avian migration patterns. However, data deriving from bird ringing has been used in an array of other disciplines including population monitoring, changes in demography, conservation management and to study the effects of climate change to name a few. Despite the widespread usage and importance, there are no guidelines available specifically describing the practice of data management, preparation and analyses of ringing datasets. Here, we present the first of a series of comprehensive tutorials that may help fill this gap. We describe in detail and through a real-life example the intricacies of data cleaning and how to create a data table ready for analy- ses from raw ringing data in the R software environment. Moreover, we created and present here the R package; ringR, designed to carry out various specific tasks and plots related to bird ringing data. Most methods described here can also be applied to a wide range of capture-recapture type data based on individual marking, regardless to taxa or research question. Keywords: data cleaning, R statistical software, banding data, statistical analysis, mark-recapture, data management Összefoglalás Feltehetően a madárgyűrűzésből származó adatok szolgáltatják a leghosszabb időtávot felölelő és legtöbb adatot tartalmazó gerinces adatbázist a Földön. -

ADU Guide 5 SAFRING Bird Ringing Manual

ADU Guide 5 SAFRING Bird Ringing Manual S.J. de Beer G.M. Lockwood J.H.F.A. Raijmakers J.M.H. Raijmakers W.A. Scott H.D. Oschadleus L.G. Underhill Cape Town, July 2001 Avian Demography Unit DEA & T The Avian Demography Unit (ADU) is a research unit of the University of Cape ADU Guide 5 Town. It conducts research in partnership with BirdLife South Africa. The ADU provides a channel through which birders can make a unique and significant input to the science of ornithology. BirdLife South Africa members form a net- work of observers who contribute data to projects coordinated by the ADU. The SAFRING ADU produces the newsletter Bird Numbers twice a year. The mission of the Avian Demography Unit is to contribute to the improved Bird Ringing Manual understanding of bird populations, especially bird population dynamics, and thus make a contribution to bird conservation. The Avian Demography Unit achieves this through mass-participation projects, long-term monitoring, innovative statistical modelling, and population-level interpretation of results. The empha- sis is on the curation, analysis, publication and dissemination of data. S.J. de Beer ADU Guides provide information on projects of the Avian Demography Unit G.M. Lockwood at the University of Cape Town. J.H.F.A. Raijmakers Birders interested in being involved in projects of the ADU should write to: J.M.H. Raijmakers Avian Demography Unit, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa, tel. (021) 650-2423, e-mail [email protected]. W.A. Scott Other publications in this series: H.D. -

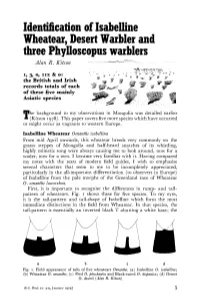

Identification of Isabelline Wheatear, Desert Warbler and Three Phylloscopus Warblers Alan R

Identification of Isabelline Wheatear, Desert Warbler and three Phylloscopus warblers Alan R. Kitson i, 3, o, ii2 & o: the British and Irish records totals of each of these five mainly Asiatic species he background to my observations in Mongolia was detailed earlier T(Kitson 1978). This paper covers five more species which have occurred or might occur as vagrants to western Europe. Isabelline Wheatear Oenanthe isabellina From mid April onwards, this wheatear breeds very commonly on the grassy steppes of Mongolia and half-heard snatches of its whistling, highly mimetic song were always causing me to look around, now for a wader, now for a tern. I became very familiar with it. Having compared my notes with the texts of modern field guides, I wish to emphasise several characters that seem to me to be incompletely appreciated, particularly in the all-important differentiation (to observers in Europe) of Isabelline from the pale morphs of the Greenland race of Wheatear 0. oenanthe leucorrhoa. First, it is important to recognise the differences in rump- and tail- pattern of wheatears. Fig. 1 shows these for five species. To my eyes, it is the tail-pattern and tail-shape of Isabelline which form the most immediate distinctions in the field from Wheatear. In that species, the tail-pattern is essentially an inverted black T abutting a white base; the a bed Fig. 1. Field appearance of tails of five wheatears Oenanthe. (a) Isabelline 0. isabellina; (b) Wheatear 0. oenanthe; (c) Pied 0. pleschanka and Black-eared 0. hispanica; (d) Desert 0. deserti (Alan R. -

Capturing Birds with Mist Nets: a Review

Capturingbirds with mist nets: A review Brt•mE. Keyesand Chr/sflanE. Grue provementshave been made in their design.These in- heovermist 300netyears was agodeveloped as a techniquebyJapanese for capturing hunters clude a choiceof smallerand larger meshsizes and the birds for food (Austin1947, Spencer 1972). Today mist replacementof cotton,silk, and nylon webbing with netsare undoubtedlythe mostcommonly used method monofilamentnylon and terylenefor increasedstrength for capturingbirds for research(Spencer 1972). As a and durability.Mist netswith a varietyof specifications result, many improvementsand modificationsin mist are now available commercially.Consult recent issues nets and their use have been suggestedby nettersfor of thisand otherornithological iournals for suppliers. particularspecies and habitats.With a few exceptions, Black mist nets are used most often since this color thisinformation is widely scatteredthroughout the orni- absorbsrather than reflectslight. However, othercolors thologicalliterature. Low (1957)has describedbasic mist-netoperations. Methods for mist-nettingin adverse are available for specifichabitat conditions.For exam- weatherconditions or particularhabitats have been de- ple,fine sand-colored nets have been effective in cap- turing shorebirdsin open-beachareas (Bleitz 1961). scribedby Bleitz (1970)and Spencer(1972). The most Pale green-aqua,dark green, dark brown, and white comprehensivereviews of mist-nettingtechniques pres- netshave alsobeen usedsuccessfully in marshes,for- ently available to netters are those of Wilson et al. ests and fields, mud flats, and snow-covered areas, re- (1965]and Bub (1967].In this paper we provide a re- spectively(Bleitz 1962b, 1964). view suitablefor both novice and experiencednetters emphasizingNorth Americanbird speciesand habitats. Various net sizes are also available. The standard mist net measuresabout 2 x 9 m (7 x 30 ft).