River Farms to Urban Towers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air and Space Museum to Undergo Major Construction

January 2018 Circulation 13,000 FREE PAUL "SOUTH" TAYLOR DESERVES HIS PRAISE Page 2 CIRCULATOR Coming Back to SW? Page 3 Air and Space Museum to Undergo Major Construction OP-ED: he first major construction project years. • $250 million: fundraising goal AMIDON IS THE for the Air and Space Museum will • All 23 galleries and presentation spac- • 1,441: newly displayed artifacts T start this summer. es will be transformed. • 7: years scheduled for completion PLACE TO BE • The museum is raising $250 mil- • 0: days closed for construction The facts: lion through private donations to fund The museum has released artist ren- Page 4 • This is the first major construction the future galleries. derings highlighting the exciting changes project for the building in Southwest • The project also includes the complete to come. These renderings (above) rep- Washington, DC, since its opening 41 re-facing of the exterior stone, replace- resent the first nine galleries scheduled years ago. ment of outdated mechanical systems, for renovation. New galleries will be orga- • Visitors will start seeing changes to the and other improvements supported by nized by theme, helping you find your museum in summer 2018. federal funding. favorite stories and make connections COMMUNITY • The museum will remain open through across eras. the project by dividing the construction By the numbers: All information and images courtesy of CALENDAR into two major phases. • 13,000 – stone slabs replaced the Smithsonian National Air and Space • The project is scheduled to take seven • 23: new galleries or presentation spaces Museum. Page 6 MRS. THURGOOD MARSHALL & HER HUSBAND Page 8 FIND US ONLINE AT THESOUTHWESTER.COM, OR @THESOUTHWESTER @THESOUTHWESTER /THESOUTHWESTERDC Published by the Southwest Neighborhood Assembly, Inc. -

1542‐1550 First Street, Sw Design Review

COMPREHENSIVE TRANSPORTATION REVIEW 1542‐1550 FIRST STREET, SW DESIGN REVIEW WASHINGTON, DC August 4, 2017 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 17-13 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia CASE NO.17-13 DeletedEXHIBIT NO.17A Prepared by: 1140 Connecticut Avenue NW 3914 Centreville Road 15125 Washington Street Suite 600 Suite 330 Suite 136 Washington, DC 20036 Chantilly, VA 20151 Haymarket, VA 20169 Tel: 202.296.8625 Tel: 703.787.9595 Tel: 703.787.9595 Fax: 202.785.1276 Fax: 703.787.9905 Fax: 703.787.9905 www.goroveslade.com This document, together with the concepts and designs presented herein, as an instrument of services, is intended for the specific purpose and client for which it was prepared. Reuse of and improper reliance on this document without written authorization by Gorove/Slade Associates, Inc., shall be without liability to Gorove/Slade Associates, Inc. Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Contents of Study .................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Study Area Overview ................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Lil^S^ OWNER©S NAME: Harbour Square Owners, Inc

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) C OMMON: Wheat Row AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET ANCJNUMBER: 1315, 1317, 1319, and 1321 Fourth Street, S.W. CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Congressman Washington Walter E STATE COUNTY: District of Columbia IT District of Columbia 001 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC D District (3 Building Public Public Acquisition: (X] Occupied Yes: jjj] Restricted CD Site Q Structure Private Q In Process [ I Unoccupie©d | | Unrestricted D Object Both | | Being Considered n Preservation work in progress a NO PRESEN T USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) I I Agricultural I | Government D Park Transportation Q Commercial Q Industrial [K] Private Residence Other (Sped #....*"V/> T> X^ I | Educational O Military | | Religious ft7%0\.. I | Entertainment II Museum | | Scientific liL^s^ OWNER©S NAME: Harbour Square Owners, Inc. STREET AND NUMBER: 500 N Street, S.W. CITY OR TOWN: Washington District : of Columbia COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Recorder of Deeds STREET AND NUMBER: 6th and D Streets, N«W. CITY OR TOWN: Washington District of Columbia 11 TITLE OF SURVEY: Proposed Distr ict of Columbia Additions to the National Regis ter of Historic Places recommended by the Joint Committp.p. nn DATE OF SURVEY: Federal State | | County Local 7< DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: National Capital Planning Commission STREET AND NUMBER: 1325 G Strp.Pi- CITY OR TOWN: Washington District of Columbia JLL (Check One) llent Q Good Fair Deteriorated I I Ruins fl Unexposed CONDITION (Chock One) (Check One) Altered | | Unaltered Moved [3 Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL. -

The Most Exciting Neighborhood in the History of the Nation's Capital

where DC meets waterfront experiences The Most Exciting Neighborhood in the History of the Nation’s Capital The Wharf is reestablishing Washington, DC, as a true DINE, SEE A SHOW & SHOP AT THE WHARF waterfront city and destination. This remarkable mile-long The best in dining and entertainment are finding a new home at neighborhood along the Washington Channel of the Potomac The Wharf, which offers more than 20 restaurants and food River brings dazzling water views, hot new restaurants, year- concepts from fine dining to casual cafes and on-the-go round entertainment, and waterside style all together in one gourmet on the waterfront. The reimagined Wharf stays true to inspiring location. The Wharf, situated along the District of its roots with the renovation and expansion of DC’s iconic Columbia’s Southwest Waterfront just blocks south of the Municipal Fish Market, the oldest continuously operating fish National Mall, is easily accessible to the region. Opened in market in the US. In addition, The Wharf features iconic shops October 2017, The Wharf features world-class residences, and convenient services including Politics and Prose, District offices, hotels, shops, restaurants, cultural, private event, Hardware and Bike, Anchor on board with West Marine, Harper marina, and public spaces, including waterfront parks, Macaw, and more. promenades, piers, and docks. Phase 2 delivers in 2022. The Wharf is also becoming DC’s premier entertainment EXPLORE THE WHARF destination. The entertainment scene is anchored by The Anthem, a concert and events venue with a variable capacity The Wharf reconnects Washington, DC, to its waterfront from 2,500 to 6,000 people that is operated by IMP, owners of on the Potomac River. -

Southwest Waterfront Redevelopment

SOUTHWEST WATERFRONT REDEVELOPMENT STAGE 2 PUD – PHASE I HOFFMAN-STRUEVER WATERFRONT, L.L.C. APPLICATION TO THE D.C. ZONING COMMISSION FOR A SECOND STAGE PLANNED UNIT DEVELOPMENT STATEMENT OF THE APPLICANT February 3, 2012 Submitted by: HOLLAND & KNIGHT LLP 2099 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Suite 100 Washington, D.C. 20006 (202) 955-3000 Norman M. Glasgow, Jr. Mary Carolyn Brown ZONING COMMISSION Counsel for the Applicant District of Columbia ZONING COMMISSION Case No. 11-03A District of Columbia CASE NO.11-03A 2 EXHIBIT NO.2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE .......................................................................................................................................... iii DEVELOPMENT TEAM ...................................................................................................................... v LIST OF EXHIBITS ........................................................................................................................... viii I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1 A. Overview ......................................................................................................................... 1 B. The Applicant and Development Team .......................................................................... 2 II. APPROVED STAGE 1 PUD DEVELOPMENT PARAMETER ............................................................. 4 III. PROPOSED VERTICAL DEVELOPMENT....................................................................................... -

Director Inter-American Defense College Fort Lesley J

DIRECTOR INTER-AMERICAN DEFENSE COLLEGE FORT LESLEY J. McNAIR WASHINGTON, DC 20319-5066 Crisis Action Team (CAT) Message #94 (CAT – 9420) D.C. Road Closures and Parking Restrictions for Friday, 28 August March for Racial Justice . 27 August 2020 SG: “Social Distancing does not mean Social Disengagement, Keep in touch with each other” 1. Purpose. To communicate to all IADC assigned personnel, the latest guidance, directive, orders, and news received regarding the IADC response to crises. 2. Applicability. This guidance applies to all IADC assigned personnel, including military members, civilians, and contractors. 3. General. The College priority is maintaining the welfare and safety of personnel and families while ensuring the continuity of our mission. Although all U.S. jurisdictions have commenced easing of some COVID-19 restrictions previously implemented, many regions are experiencing an uptick in cases, including the NCR. All personnel should remain attentive to updated guidance or directives issued by local, state, and national level authorities designed to minimize the spread of the virus and prevent a resurgence. 4. Information. The District of Columbia March for Racial Justice will occur on Friday, 28 August. Drivers can expect major road closures in D.C. on Friday as thousands are expected to participate in a march against police brutality. a. Protesters with the "Commitment March: Get Your Knee Off our Necks” will gather starting at 7 a.m. and eventually march from the Lincoln Memorial to the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial. -

International Business Guide

WASHINGTON, DC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS GUIDE Contents 1 Welcome Letter — Mayor Muriel Bowser 2 Welcome Letter — DC Chamber of Commerce President & CEO Vincent Orange 3 Introduction 5 Why Washington, DC? 6 A Powerful Economy Infographic8 Awards and Recognition 9 Washington, DC — Demographics 11 Washington, DC — Economy 12 Federal Government 12 Retail and Federal Contractors 13 Real Estate and Construction 12 Professional and Business Services 13 Higher Education and Healthcare 12 Technology and Innovation 13 Creative Economy 12 Hospitality and Tourism 15 Washington, DC — An Obvious Choice For International Companies 16 The District — Map 19 Washington, DC — Wards 25 Establishing A Business in Washington, DC 25 Business Registration 27 Office Space 27 Permits and Licenses 27 Business and Professional Services 27 Finding Talent 27 Small Business Services 27 Taxes 27 Employment-related Visas 29 Business Resources 31 Business Incentives and Assistance 32 DC Government by the Letter / Acknowledgements D C C H A M B E R O F C O M M E R C E Dear Investor: Washington, DC, is a thriving global marketplace. With one of the most educated workforces in the country, stable economic growth, established research institutions, and a business-friendly government, it is no surprise the District of Columbia has experienced significant growth and transformation over the past decade. I am excited to present you with the second edition of the Washington, DC International Business Guide. This book highlights specific business justifications for expanding into the nation’s capital and guides foreign companies on how to establish a presence in Washington, DC. In these pages, you will find background on our strongest business sectors, economic indicators, and foreign direct investment trends. -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

Phase 1 Site-Generated Peak Hour Volumes (1 of 3)

Figure 38: Phase 1 Site-Generated Peak Hour Volumes (1 of 3) 76 Figure 39: Phase 1 Site-Generated Peak Hour Volumes (2 of 3) 77 Figure 40: Phase 1 Site-Generated Peak Hour Volumes (3 of 3) 78 Figure 41: 2022 Interim (with Phase 1) Peak Hour Traffic Volumes (1 of 3) 79 Figure 42: 2022 Interim (with Phase 1) Peak Hour Traffic Volumes (2 of 3) 80 Figure 43: 2022 Interim (with Phase 1) Peak Hour Traffic Volumes (3 of 3) 81 Figure 44: Outbound Trip Distribution and Routing 82 Figure 45: Inbound Trip Distribution and Routing 83 Figure 46: Phase 2 Access Specific Outbound Trip Distribution and Routing 84 Figure 47: Phase 2 Access Specific Inbound Trip Distribution and Routing 85 Figure 48: Phase 2 Site-Generated Peak Hour Volumes (1 of 3) 86 Figure 49: Phase 2 Site-Generated Peak Hour Volumes (2 of 3) 87 Figure 50: Phase 2 Site-Generated Peak Hour Volumes (3 of 3) 88 Figure 51: 2022 Future (with Phase 1 and Phase 2) Peak Hour Traffic Volumes (1 of 3) 89 Figure 52: 2022 Future (with Phase 1 and Phase 2) Peak Hour Traffic Volumes (2 of 3) 90 Figure 53: 2022 Future (with Phase 1 and Phase 2) Peak Hour Traffic Volumes (3 of 3) 91 Figure 54: 2022 Background without Development Lane Configurations and Traffic Controls (1 of 3) 92 Figure 55: 2022 Background without Development Lane Configurations and Traffic Controls (2 of 3) 93 Figure 56: 2022 Background without Development Lane Configurations and Traffic Controls (3 of 3) 94 Figure 57: 2022 Interim with Phase 1 Lane Configurations and Traffic Controls (1 of 3) 95 Figure 58: 2022 Interim with Phase -

Potomac Park

46 MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN EDAW Enhance the Waterfront Experience POTOMAC PARK Potomac Park can be reimagined as a unique Washington destination: a prestigious location extending from the National Mall; a setting of extraordinary beauty and sweeping waterfront vistas; an opportunity for active uses and peaceful solitude; a resource with extensive acreage for multiple uses; and a shoreline that showcases environmental stewardship. Located at the edge of a dense urban center, Potomac Park should be an easily accessible place that provides opportunities for water-oriented recreation, commemoration, and celebration in a setting that preserves the scenic landscape. The park offers great potential to relieve pressure on the historic and fragile open space of the National Mall, a vulnerable resource that is increasingly overburdened with demands for large public gatherings, active sport fields, everyday recreation, and new memorials. Potomac Park and its shoreline should offer a range of activities for the enjoyment of all. Some areas should accommodate festivals, concerts, and competitive recreational activities, while other areas should be quiet and pastoral to support picnics under a tree, paddling on the river, and other leisure pastimes. The park should be connected with the region and with local neighborhoods. MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN 47 ENHANCE THE WATERFRONT EXPERIENCE POTOMAC PARK Context Potomac Park is a relatively recent addition to Ohio Drive parallels the walkway, provides vehicular Washington. In the early years of the city it was an access, and is used by bicyclists, runners, and skaters. area of tidal marshes. As upstream forests were cut The northern portion of the island includes 25 acres and agricultural activity increased, the Potomac occupied by the National Park Service’s regional River deposited greater amounts of silt around the headquarters, a park maintenance yard, offices for the developing city. -

Chapter 9: Designated Entertainment Area Signs

CHAPTER 9: DESIGNATED ENTERTAINMENT AREA SIGNS 900 APPLICABILITY 900.1 This chapter shall govern signs within Designated Entertainment Areas (DEAs). 900.2 DEAs shall include the following: (a) The Gallery Place Project, comprising of property and building located at Square 455, Lot 50 and the private alley located between the project and the property known as the Verizon Center, Square 455, Lot 47; and the northern façade of the Verizon Center; (b) The Verizon Center property and building located at Square 455, Lot 47, including the Gallery Place Metro Entrance on the corner of 7th and F Streets, NW; (c) The Ballpark Area between South Capitol Street, SE, and First Street, SE, from M Street, SE, to Potomac Avenue, SE; (d) The Southwest Waterfront (SW Waterfront), including the Southwest Fish Market, between Maine Avenue, SE, and the Washington Channel, from the 12th Street Expressway to a line north of M Street, SW, as it would be extended to Washington Channel; and (e) Other areas the Mayor designates as a result of a process determined by the Mayor which shall include consultation with the Office of Planning, the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs (DCRA), the District Department of Transportation (DDOT), the appropriate Advisory Neighborhood Commissions (ANCs), and appropriate federal agencies if required based on the location of the proposed DEA. 900.2(a) The Gallery Place Project 900.2(b) The Verizon Center 900.2(c) The Ballpark Area 900.2(d) SW Waterfront and Fish Market 900.3 DEA signs may include projections of static or moving images onto: (a) The Gallery Place Project, including the private alley located between the Project and the property known as the Verizon Center; (b) Buildings in squares 700 and 701 within the Ballpark area, with the exception of any façade facing South Capitol Street; and (c) Non-residential buildings within the SW Waterfront, with the exception of any façade facing Maine Avenue, SW. -

Ty 2022 Dc Otr Rpta

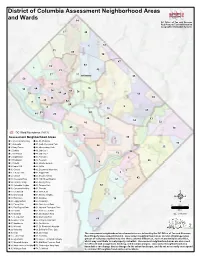

District of Columbia Assessment Neighborhood Areas and Wards 14 DC Office of Tax and Revenue Real Property Tax Administration Geographic Information Systems 27 48 6 51 11 60 12 47 49 53 1 21 42 37 17 35 50 13 7 30 54 15 34 61 36 70 55 24 56 71 38 66 26 4 62 29 31 8 5 19 65 23 40 41 25 44 63 52 10 32 20 18 DC Ward Boundaries (2012) 72 39 Assessment Neighborhood Areas 9 1, American University 36, Mt. Pleasant 33 2, Anacostia 37, North Cleveland Park 46 3, Barry Farms 38, Observatory Circle 22 4, Berkley 39, Old City 1 64 5, Brentwood 40, Old City 2 73 6, Brightwood 41, Palisades 2 7, Brookland 42, Petworth 28 74 8, Burleith 43, Randle Heights 9, Capitol Hill 44, NoMa 10, Central 46, Southwest Waterfront 3 11, Chevy Chase 47, Riggs Park 3 12, Chillum 48, Shepherd Park 43 13, Cleveland Park 49, 16th Street Heights 67 14, Colonial Village 50, Spring Valley 15, Columbia Heights 51, Takoma Park 68 16, Congress Heights 52, Trinidad 17, Crestwood 53, Wakefield 18, Deanwood 54, Wesley Heights 19, Eckington 55, Woodley 16 20, Foggy Bottom 56, Woodridge 4 21, Forest Hills 60, Rock Creek Park 0 0.5 1 22, Fort Dupont Park 61, National Zoological Park 23, Foxhall 62, Rock Creek Park Miles 24, Garfield 63, DC Stadium Area Date: 2/19/2021 25, Georgetown 64, Anacostia Park 69 26, Glover Park 65, National Arboretum 27, Hawthorne 66, Fort Lincoln 28, Hillcrest 67, St.