By Adam and Missy Andrews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kipling 'If–' and Other Poems Rudyard Kipling

M I C H A E L O ’ M A R A T I T L E I N F O R M A T I O N M I C H A E L O ' M A R A Kipling 'If–' and Other Poems Rudyard Kipling Keynote This pocket-sized selection of Rudyard Kipling’s verse contains not only this classic, but many of his greatest poems, in testimony to a writer who possessed a precocious gift for rhyme and a brilliant ear for language. Description ‘If–‘ is, by British readers’ choice, the most popular poem in the language. Publication date Thursday, November 03, 2016 This pocket-sized selection of Rudyard Kipling’s verse contains not only this classic, but Price £4.99 many of his greatest poems, in testimony to a writer who possessed a precocious gift for rhyme and a brilliant ear for language, coupled with a pin-sharp use of spare, vivid ISBN-13 9781782437109 imagery. Binding Paperback This pocket-sized selection includes: ‘Tommy’, ‘The Way Through the Woods’, Format 144 x 111 mm ‘Recessional’, ‘Boots’, ‘The Female of the Species’, ‘Mandalay’, ‘Gunga Din’, The Young Depth 9.5mm British Soldier’ and many more of Kipling’s greatest poems. Extent 128 pages Word Count Sales Points Territorial Rights World Includes forty of his well-known poems such as ‘If…’, ‘The Ballad of East and West’ and In-House Editor Louise Dixon ‘For All We Have and Are’ The Pocket Poets series makes the perfect gift Also available in the Pocket Poets series: Burns, Keats and Wordsworth Comparative titles: The Emergency Poet (9781782434054), pub date: 01/10/2015 The Everyday Poet (9781782436577), pub date 06/10/2016 Author Biography Born in 1865 in India, and educated in England, Rudyard Kipling returned to India in 1882 to work as a journalist. -

George Orwell Boys' Weeklies

George Orwell Boys' weeklies You never walk far through any poor quarter in any big town without coming upon a small newsagent's shop. The general appearance of these shops is always very much the same: a few posters for the Daily Mail and the News of the World outside, a poky little window with sweet-bottles and packets of Players, and a dark interior smelling of liquorice allsorts and festooned from floor to ceiling with vilely printed twopenny papers, most of them with lurid cover-illustrations in three colours. Except for the daily and evening papers, the stock of these shops hardly overlaps at all with that of the big news-agents. Their main selling line is the twopenny weekly, and the number and variety of these are almost unbelievable. Every hobby and pastime — cage-birds, fretwork, carpentering, bees, carrier-pigeons, home conjuring, philately, chess — has at least one paper devoted to it, and generally several. Gardening and livestock-keeping must have at least a score between them. Then there are the sporting papers, the radio papers, the children's comics, the various snippet papers such as Tit-bits, the large range of papers devoted to the movies and all more or less exploiting women's legs, the various trade papers, the women's story-papers (the Oracle, Secrets, Peg's Paper, etc. etc.), the needlework papers — these so numerous that a display of them alone will often fill an entire window — and in addition the long series of ‘Yank Mags’ (Fight Stories, Action Stories, Western Short Stories, etc.), which are imported shop-soiled from America and sold at twopence halfpenny or threepence. -

Knowledge 3 Teacher Guide Grade 1 Different Lands, Similar Stories Grade 1 Knowledge 3 Different Lands, Similar Stories

¬CKLA FLORIDA Knowledge 3 Teacher Guide Grade 1 Different Lands, Similar Stories Grade 1 Knowledge 3 Different Lands, Similar Stories Teacher Guide ISBN 978-1-68391-612-3 © 2015 The Core Knowledge Foundation and its licensors www.coreknowledge.org © 2021 Amplify Education, Inc. and its licensors www.amplify.com All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts and CKLA are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. References herein should not be regarded as affecting the validity of said trademarks and trade names. Printed in the USA 01 BR 2020 Grade 1 | Knowledge 3 Contents DIFFERENT LANDS, SIMILAR STORIES Introduction 1 Lesson 1 Cinderella 6 Introducing the Read-Aloud (10 min) Read-Aloud (30 min) Application (20 min) • Core Connections/Domain • Purpose for Listening • Vocabulary Instructional Activity: Introduction Instructions • “Cinderella” • Where Are We? • Somebody Wanted But So Then • Comprehension Questions • Word Work: Worthy Lesson 2 The Girl with the Red Slippers 22 Introducing the Read-Aloud (10 min) Read-Aloud (30 min) Application (20 min) • What Have We Already Learned? • Purpose for Listening • Drawing the Read-Aloud • Where Are We? • “The Girl with the Red Slippers” • Comprehension Questions • Word Work: Cautiously Lesson 3 Billy Beg 36 Introducing the Read-Aloud (10 min) Read-Aloud (30 min) Application (20 min) • What Have We Already Learned? • Purpose for Listening • -

Comic Annuals for Christmas

Christmas annuals: They were once as much a part of the festive celebration as turkey and the trimmings. Steve Snelling recalls Christmases past with comic immortals like Alf Tupper, Robot Archie and Lonely Larry Comic season’s greetings from all my heroes ostalgia’s a funny thing. I like to But, thankfully, such illusions would remain think of it as a feelgood trick of the unshattered for a little longer and, though I memory where all pain and didn’t know it then, that less than surprising discomfort is miraculously excised gift from a most un-grotto-like publishing and the mind’s-eye images are house on the edge of Fleet Street marked the forever rose-tinted. And while it may beginning of a Christmas love affair with the not always be healthy to spend too much time comic annual that even now shows precious Nliving in the past, I doubt I’m alone in finding it little sign of waning. strangely comforting to occasionally retreat Of course, much has changed since that down my own private Christmas morning when I tore open the memory lane. festive wrapping to reveal the first-ever Christmas is a case in Victor Book for Boys, its action-packed cover point. No matter how hard featuring a fearsome-looking bunch of Tommy- I might try, nothing quite gun wielding Commandos pouring from the measures up to visions of battered bows of the destroyer Campbeltown festive times past when to moments after it had smashed into the dock revel in the beguiling magic gates of St Nazaire. -

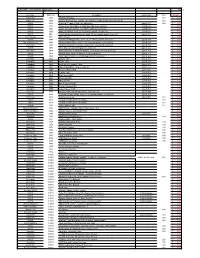

Lledoshuffle - New Stock List, August 2020 Page 1

lledoshuffle - new stock list, August 2020 Page 1 Box Type Model no. Description Comments box Website MoDG Fat 3006 Matthew Norman 903 £ 2.50 MoDG Fat 4000 Victoria & Kings Cross, Liptons Tea - white on green, brown seats (version d) 903 £ 4.00 MoDG 6016 Ovaltine 75 years, stone roof, beige logo type A-C-A 226 £ 3.00 MoDG 6024 Kodak, brass 12 wheels, no steering wheel, brass radiator type B-C-A £ 2.50 MoDG 6024 Kodak, white 20 wheels, no steering whee, brass radiator type B-C-A £ 2.50 MoDG 6025 Marks & Spencer, brass 12, no steering wheel, chrome rad. type B-C-A £ 2.50 MoDG 6042 Cwm Dale Spring (blue chassis), black 20, no steering wheel, brass rad. type A-C-A £ 2.50 Alton Towers 6044 Alton Towers £ 2.50 MoDG 6047 John Smiths Magnet Ales, brass 12, no steering wheel, brass rad. type A-C-A £ 2.50 Bay to Birdwood 6048 Bay to Birdwood Run, brass 12, no steering wheel, brass radiator type B-C-A £ 3.00 Cadburys 6051 Cadburys Drinking Chocolate, cream tyres, maroon 20, brass rad type B-C-A £ 3.00 MoDG 6053 Tizer, brass 12, no steering wheel, brass rad. type A-C-A £ 2.50 Coca Cola 6058 Drink Coca Cola, in Sterilized Bottles - cream tyres, red 20, brass rad. type B-E-A £ 3.00 MoDG 6068 Golden Shred, brass 12 wheels, no steering wheel type B-E-A £ 2.50 MoDG 6069 Charringtons, brass 12, no steering wheel, chrome rad. type A-E-A £ 2.50 Canadian 6074 Ontario 1867 type A-E-A £ 4.00 Canadian 6075 Yukon 1870 type A-E-A £ 4.00 Canadian 6076 North West Territories 1870 type A-E-A £ 4.00 Canadian 6077 Prince Edward Isle 1870 (version a) type A-E-A £ 4.00 -

Phenomenology of Space and Time in Rudyard Kipling's Kim: Understanding Identity in the Chronotope

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English Spring 4-6-2012 Phenomenology of Space and TIme in Rudyard Kipling's Kim: Understanding Identity in the Chronotope Daniel S. Parker Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Recommended Citation Parker, Daniel S., "Phenomenology of Space and TIme in Rudyard Kipling's Kim: Understanding Identity in the Chronotope." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/132 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PHENOMENOLOGY OF SPACE AND TIME IN RUDYARD KIPLING’S KIM: UNDERSTANDING IDENTITY IN THE CHRONOTOPE by DANIEL SCOTT PARKER Under the Direction of LeeAnne Richardson ABSTRACT This thesis intends to investigate the ways in which the changing perceptions of landscape during the nineteenth century play out in Kipling’s treatment of Kim’s phenomenological and epistemological questions of identity by examining the indelible influence of space— geopolitical, narrative, and imaginative—on Kim’s identity. By interrogating the extent to which maps encode certain ideological assumptions, I will assess the problematic issues of Kim’s multi-faceted identity through an exploration of -

SB-4309-March-NA.Pdf

Scottishthethethethe www.scottishbanner.com Banner 37 Years StrongScottishScottishScottish - 1976-2013 Banner A’BannerBanner Bhratach Albannach 44 Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Years Strong - 1976-2020 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 43 36 36 NumberNumber Number 911 11The The The world’s world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international Scottish Scottish newspaper newspaper newspaper May MarchMay 2013 2013 2020 The Broar Brothers The Rowing Scotsmen » Pg 16 Celebrating USMontrose Barcodes Scotland’s first railway through The 1722 Waggonway 7 25286 844598 0 1 » Pg 8 the ages » Pg 14 Highland, 7 25286 844598 0 9 Scotland’s Bard through Lowlands, the ages .................................................. » Pg 3 Final stitches sewn into Arbroath Tapestry ............................ » Pg 9 Our Lands A Heritage of Army Pipers .......... » Pg 32 7 25286 844598 0 3 » Pg 27 7 25286 844598 1 1 7 25286 844598 1 2 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Volume 43 - Number 9 Scottishthe Banner The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Offices of publication Valerie Cairney Australasian Office: PO Box 6202 Editor Bagpipes-the world’s instrument Marrickville South, Sean Cairney NSW, 2204 pipes attached where the legs and In this issue Tel:(02) 9559-6348 EDITORIAL STAFF neck would be. Today you will find The sound of Scotland made its way Jim Stoddart [email protected] both synthetic and leather varieties recently across the Atlantic Ocean The National Piping Centre available, with fans of each. -

THE GREY FAIRY BOOK by Various

THE GREY FAIRY BOOK By Various Edited by Andrew Lang Preface The tales in the Grey Fairy Book are derived from many countries— Lithuania, various parts of Africa, Germany, France, Greece, and other regions of the world. They have been translated and adapted by Mrs. Dent, Mrs. Lang, Miss Eleanor Sellar, Miss Blackley, and Miss hang. 'The Three Sons of Hali' is from the last century 'Cabinet des Fees,' a very large collection. The French author may have had some Oriental original before him in parts; at all events he copied the Eastern method of putting tale within tale, like the Eastern balls of carved ivory. The stories, as usual, illustrate the method of popular fiction. A certain number of incidents are shaken into many varying combinations, like the fragments of coloured glass in the kaleidoscope. Probably the possible combinations, like possible musical combinations, are not unlimited in number, but children may be less sensitive in the matter of fairies than Mr. John Stuart Mill was as regards music. Donkey Skin There was once upon a time a king who was so much beloved by his subjects that he thought himself the happiest monarch in the whole world, and he had everything his heart could desire. His palace was filled with the rarest of curiosities, and his gardens with the sweetest flowers, while in the marble stalls of his stables stood a row of milk-white Arabs, with big brown eyes. Strangers who had heard of the marvels which the king had collected, and made long journeys to see them, were, however, surprised to find the most splendid stall of all occupied by a donkey, with particularly large and drooping ears. -

A Bibliography of the Works of Rudyard Kipling (1881-1921)

GfarneU UntUKtattjj Siibrarg 3tlrara, Htm $nrk BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF HENRY W. SAGE 1891 Cornell University Library Z8465 -M38 1922 Bibliography of the works of Rudyard Kip 3 1924 029 624 966 olin The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://archive.org/details/cu31924029624966 Of this booh 450 copies have been printed, of which £00 are for sale. This is No.M TO MY MOTHER A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RUDYARD KIPLING c o o o ^ U rS Frontispiece.} A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE WORKS OF RUDYARD KIPLING (1881—1921) X ,' ^ BY E. W. MARTINDELL, M.A.IOxon.), F.R.A.I. Bairister-at-Law. LONDON THE BOOKMAN'S JOURNAL 173, FLEET STREET, E.C.4. NEW YORK JAMES F. DRAKE. INC. 1922 z f\5as oz^l — PREFACE To the fact that in the course of many years I gathered tog-ether what became known as the most comprehensive collection of the writings of Rudyard Kipling, and to the fact that no-one has compiled an exhaustive bibliography of these writings is due this work. How great has been the need for a full and up to date bibliography of Kipling's works needs no telling. From Lahore to London and from London to New York his various publishers have woven a bibliographical maze such as surely can hardly be paralleled in the literature about literature. The present attempt—the first which has been made in England, so far as I know, on any extensive scale—to form a detailed guide to this bibliographical maze is necessarily tentative; and despite all errors and omissions, for which, as a mere tyro, I crave indulgence, I trust that the following pages will provide not only a handy record for collectors of the writings of our great imperialist poet and novelist, but a basis for the fuller and more perfect work, which the future will bring forth. -

Some Political Implications in the Works of Rudyard Kipling

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1946 Some Political Implications in the Works of Rudyard Kipling Wendelle M. Browne Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Browne, Wendelle M., "Some Political Implications in the Works of Rudyard Kipling" (1946). Master's Theses. 74. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/74 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1946 Wendelle M. Browne SOME POLITICAL IMPLICATIONS IN THE WORKS OF RUDYARD KIPLING by Wendelle M. Browne A Thesis Submitted as Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Loyola University May 1946 VITA Wendelle M. Browne was born in Chicago, Illinois, March 2£, 1913. She was graduated from the Englewood High School, Chicago, Illinois, June, 1930 and received a teaching certificate from The Chicago Normal College in June 1933. The Bachelor of Science Degree in the depart~ent of Education was conferred by the University of Illinois in June, 1934. From 1938 to the present time the writer has been engaged as a teacher in the elementary schools of Chicago. During the past five years she has devoted herself to graduate study in English at Loyola University in Chicago. -

Hornblower and the Hotspur

Hornblower and the Hotspur Horatio Hornblower, #3 (April 18o3 - May 18o5) by Cecil S. Forester, 1899-1966 Published: 1962 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Chapter 1 … thru … Chapter 25 J J J J J I I I I I Chapter 1 „REPEAT after me,“ said the parson. „I Horatio, take thee, Maria Ellen—“ The thought came up in Hornblower‘s mind that these were the last few seconds in which he could withdraw from doing something which he knew to be ill-considered. Maria was not the right woman to be his wife, even admitting that he was suitable material for marriage in any case. If he had a grain of sense, he would break off this ceremony even at this last moment, he would announce that he had changed his mind, and he would turn away from the altar and from the parson and from Maria, and he would leave the church a free man. „To have and to hold—“ he was still, like an automaton, repeating the parson‘s words. And there was Maria beside him, in the white that so little became her. She was melting with happiness. She was consumed with love for him, however misplaced it might be. He could not, he simply could not, deal her a blow so cruel. He was conscious of the trembling of her body beside him. He could no more bring himself to shatter that trust than he could have refused to command the HOTSPUR. „And thereto I plight thee my troth,“ repeated Hornblower. -

1992-05-Collectorsdigest-V46-N545

The following SECOND HAND but in AS NEW CONDITJON: Howard Baker - Sexton Blake. Union Jack. Lee Omnibus \Olumes. also H.B. Annuals - Greyfriars lfoliday Annuals - pre 1973 - ALL AT £6 each. out of print volumes a bit dearer. GREYfo'RIARS SCHOOL, A PROSPECTUS. £3 each. The First Boys Paper Omnibus. as new, £5 each. Other H.B. Omnibus vols - new £12.95, second hand. as ne\\, Book £8.Clubs. ncw£18,s/hasnew£9. No.41 BookClub. CHAMPION 1973 onwards. TRIUMPHS from 1932 - '38 £3 each. UON complete run from No . 1 1952 to end 1974. 1200 copies. Will separate. SCOR Cr JER complete run 190copies £70. THUNDER complete run 22 copies£ I l. SCORE complete run 39 copies £19. TIGER "Jo. l 1954 10 December 1973. 990 copies. KNOCKOUT various 1948 to '50- 60 copies. HOW ARD BAKERS. Gre) friars Librar) not £8.95 but to clear £3 each. as new. SPECIAL OFFER: Facsimiles single issues. 20 for £ I 0. post free. \fagnets. Gems etc. Book Clubs. second hand as new. St. Jim's only £6 each. Vlany more 'goodies ' during the month. Worth a \ isit. Please ring first after 2.00 p.m. You are very welcome. If you can't maJ...eit, a good postal service 1s available Ah, a) s the in rna1J...e1tor good collections or items. ln association with FLIPS PAGES (Robin Osborne) wide stock of science fic1ion and American material at mv address. · Your wants lists appreciated . NO R MAN SH AW 84 Belvedere Road, Upper Norwood. London SEI9 2HZ Tel· 081 771 9857 Nearest Station: B.R.