The Architecture of Human Composting Will Devault-Weaver A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ULI Creative Placemaking

ULI Creative Placemaking: Self‐Guided Tour of Seattle Welcome to Seattle! We invite you to use this guide, which is also accessible on the Google Maps app, under “My Places” to: 1. Tour robust and diverse developments noted for their innovative use of Creative Placemaking, the integration of arts and culture in community revitalization to build strong, healthy cities. You can get around town car‐free with an Orca Card transit pass at participating retailers or transit station kiosks. 2. Add your comments and suggestions about public and private developments that contribute to our understanding of Creative Placemaking by emailing [email protected]. 3. Keep in touch with Creative Placemaking through ULI events, resources and publications nationally at ULI.org/CreativePlacemaking and locally through your District Council: https://uli.org/councils/district‐councils/locations. Tour Guide Central Seattle Adventurous Address Public Transit Legend: Locations Locations A visual overview of 12 suggested tour locations in the central city, along with 7 additional tour locations in the surrounding areas for the adventurous types. ________________ This map can be added to or updated at: https://goo.gl/vCPf2X Page 1 of 12 ULI Creative Placemaking: Tour Sites in Central Seattle Find this information online or on your mobile device at: https://goo.gl/vCPf2X Occidental Park Description 117 S Washington St. Occidental Park is a redevelopment of a half‐acre asphalt parking lot into a vibrant, Seattle, WA 98104 verdant square, opened to the public in 1971. Today, it is home to bookstores, art galleries, ping pong tables, bocce ball courts, boutiques, unique shops and eateries. -

ULI Creative Placemaking: Self-Guided Tour of Seattle

ULI Creative Placemaking: Self-Guided Tour of Seattle Welcome to Seattle! We invite you to use this guide, which is also accessible on the Google Maps app, under “My Places” to: 1. Tour robust and diverse developments noted for their innovative use of Creative Placemaking, the integration of arts and culture in community revitalization to build strong, healthy cities. You can get around town car-free with an Orca Card transit pass at participating retailers or transit station kiosks. You can also pay on your cell phone through the Transit GO Ticket app, with cash or with a day pass. 2. Add your comments and suggestions about public and private developments that contribute to our understanding of Creative Placemaking by emailing [email protected]. 3. Keep in touch with Creative Placemaking through ULI events, resources and publications nationally at ULI.org/CreativePlacemaking and locally through your District Council: https://uli.org/councils/district-councils/locations. Tour Guide Central Seattle Adventurous Address Public Transit Legend: Locations Locations A visual overview of 12 suggested tour locations in the central city, along with 7 additional tour locations in the surrounding areas for the adventurous types. ________________ This map can be added to or updated at: https://goo.gl/vCPf2X Page 1 of 12 ULI Creative Placemaking: Tour Sites in Central Seattle Find this information online or on your mobile device at: https://goo.gl/vCPf2X Occidental Park Description 117 S Washington St. Occidental Park is a redevelopment of a half-acre asphalt parking lot into a vibrant, Seattle, WA 98104 verdant square, opened to the public in 1971. -

Con!Nui" of Norwegian Tradi!On in #E Pacific Nor#West

Con!nui" of Norwegian Tradi!on in #e Pacific Nor#west Henning K. Sehmsdorf Copyright 2020 S&S Homestead Press Printed by Applied Digital Imaging Inc, Bellingham, WA Cover: 1925 U.S. postage stamp celebrating the centennial of the 54 ft (39 ton) sloop “Restauration” arriving in New York City, carrying 52 mostly Norwegian Quakers from Stavanger, Norway to the New World. Table of Con%nts Preface: 1-41 Immigra!on, Assimila!on & Adapta!on: 5-10 S&ried Tradi!on: 11-281 1 Belief & Story 11- 16 / Ethnic Jokes, Personal Narratives & Sayings 16-21 / Fishing at Røst 21-23 / Chronicats, Memorats & Fabulats 23-28 Ma%rial Culture: 28-96 Dancing 24-37 / Hardanger Fiddle 37-39 / Choral Singing 39-42 / Husflid: Weaving, Knitting, Needlework 42-51 / Bunad 52-611 / Jewelry 62-7111 / Boat Building 71-781 / Food Ways 78-97 Con!nui": 97-10211 Informants: 103-10811 In%rview Ques!onnaire: 109-111111 End No%s: 112-1241111 Preface For the more than three decades I taught Scandinavian studies at the University of Washington in Seattle, I witnessed a lively Norwegian American community celebrating its ethnic heritage, though no more than approximately 1.5% of self-declared Norwegian Americans, a mere fraction of the approximately 280,000 Americans of Norwegian descent living in Washington State today, claim membership in ethnic organizations such as the Sons of Norway. At musical events and dances at Leikarringen and folk dance summer camps; salmon dinners and traditional Christmas celebrations at Leif Ericsson Lodge; cross-country skiing at Trollhaugen near Stampede -

Greater Seattle Referral Guide

Greater Seattle Referral Guide JayKipp.com Greater Seattle Referral Guide TABLE OF 6 Economic Snapshot 9 Job Market Outlook 11 Welcome to Seattle: A Guide For Transplants 13 Downtown Seattle Map 14 Downtown Seattle Neighborhoods 16 Seattle Map 14 Seattle Neighborhoods 25 Greater Eastside Map 26 Greater Eastside Neighborhoods 34 West Puget Sound Map 38 West Puget Sound Neighborhoods CONTENTS 2 JayKipp.com Greater Seattle Referral Guide Introduction JAY KIPP MANAGING BROKER 206.853.9153 [email protected] With 15 years of residential real estate brokerage experience, Jay brings a wealth of knowledge regarding appraisal, market analysis, capital markets and property marketing to any real estate transaction. His personal connection to real estate developers, lenders and builders also help his clients stay abreast of relevant real estate trends. Nearly forty five years of combined knowledge and service excellence, Team Kipp is a dynamic and skilled group dedicated to streamlining the real estate experience. They proudly combine a unique skill set backed with with a prestigious global brand and marketing excellence. CHRISTINE KIPP SENIOR GLOBAL REAL ESTATE ADVISOR 425.260.3934 [email protected] Christine specializes In luxury properties east of Seattle. She specializes in representing quality lifestyle properties including waterfront, view, and fine acreage estates throughout the region. Chris is recognized among peers for her accomplished sales record and for her honesty, integrity, and care with which she oversees each client’s needs. -

Sdot Art Plan

0 2005 SDOT ART PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS BOOK I : The Diagnosis ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 INTRODUCTION: Origins of the SDOT Art Plan 7 Structure & Audience 8 Objectives 8 Emerging Seattle 9 RESEARCH BACKGROUND + PROCESS: Research Methodology 10 Primer on Public Art 11 SDOT Art History 13 Other Generators of Public Art 14 Guerilla Artwork 15 TUNE-UP RECOMMENDATIONS: Overview of SDOT 19 Re-thinking Repeating Projects 20 1% for Art: Understanding the Finances 24 1% for Art: The Goal 25 Reserved for Addendum 27-34 BOOK II : The Toolkit INTRODUCTION 35 TOOLKIT: Preface / Matrix 39 Street Furniture Introduction 41 Surface Treatment Introduction 51 Art Object Introduction 59 Creative Option Introduction 66 SPECIAL PROJECTS: Preface / Matrix 73 Definitions 74 BOOK III : Sidewalk Survey INTRODUCTION 95 VISUAL SURVEY 97 SURVEY INDEX 111 PUBLIC ART READER 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 140 A Closing Poem by Lori O’Conel 141 1 2005 SDOT ART PLAN 2 2005 SDOT ART PLAN This Art Plan has been tailored for the Seattle Department of Transportation by its Artist-in-Residence in collaboration with the Mayor’s Office of Arts & Cultural Affairs My residency with the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) proved to be endlessly fascinating and rich with opportunities for theorizing about art, aesthetics, culture and the future of Seattle. I had the sincere pleasure of working closely with the Capital Projects and Roadway Structures management team for the better part of a year (part-time) and enjoyed every minute of it. I would like to extend a special thanks to members of the executive steering committee, Barbara Goldstein and Frank Yanagimachi, who did heavy lifting during the early and most active phases of the residency, though they have since moved on to do more lifting for other agencies. -

TOOLKIT Innovative VOLUME 2 Design and Development Codes

COMMUNITY INVESTMENT TOOLS COMMUNITY INVESTMENT TOOLKIT Innovative VOLUME 2 Design and Development Codes COMMUNITY INVESTMENT TOOLS COMMUNITY INVESTMENT TOOLKIT Innovative VOLUME 2 Design and Development Codes Acknowledgments The toolkit was developed through extensive research and collaboration with representatives from local governments and stakeholder groups. Developers, investors, and citizens were also involved in identifying issues and potential tools through focus groups. A public forum was held in Decem- ber, 2007 to further engage stakeholder groups and citizens. We would like to thank everyone for participating and contributing to this volume of the toolkit. In particular, we would like to express our appreciation to the following individuals: Administration Robin McArthur, Regional Planning Director Chris Deffebach, Long Range Policy and Planning Manager Paulette Copperstone, Program Assistant Project Staff Miranda Bateschell, Project Manager, Associate Regional Planner Malu Wilkinson, Principal Regional Planner Megan Gibb, TOD/Centers Program Manager Carol Hall, Data Resource Center GIS Supervisor Public Affairs and Government Relations Janice Larson, Creative Services Manager Jeanne Galick, Graphic Design Specialist Ken Ray, Senior Public Affairs Coordinator Elizabeth Adams, Production Coordinator Advisory Group Kristen Belz, City Planner, City of Portland Bureau of Planning Hal Bergsma, Principal Planner, City of Beaverton Community Development Department Dan Drentlaw, Community Development Director, City of Oregon City -

Seattle Host Committee Guide — ICMA's 101St Annual Conference

WELCOME TO THE Emerald City! Surrounded by the Cascade and Olympic mountain ranges, Lake Washington, and Puget Sound, Seattle and King County offer a rich history, one-of-a-kind attractions, a thriving cultural scene, world-class restaurants and shopping, and boundless opportunities for outdoor adventure. The Host Committee is excited to host the 101st ICMA Annual Conference and welcome you to our home. We invite you to explore the down-to-earth charm and rugged beauty of the Pacific Northwest. Read on for an introduction to some of our favorite activities and attractions throughout the region. One-of-a-Kind Attractions Within just a few blocks of the Seattle Waterfront, you’ll find many of our region’s top visitor destinations, including Pike Place Market, the Space Needle and Seattle Center, and historic Pioneer Square. • The famed Pike Place Market is a bazaar the Seattle Aquarium, and catch breathtaking views of of fresh flowers, fruit, seafood, vegetables, the skyline and Mount Rainier from the Seattle Great ethnic eateries, and specialty shops over- Wheel, a 175-foot Ferris wheel at Pier 57. looking Elliott Bay. The oldest continually • Constructed for the 1962 World's Fair, Seattle Center operating farmers market in the United is home to our city’s most recognizable symbol, the States, this is the place to watch fish- Space Needle. At Seattle Center, you can journey sky- mongers tossing salmon, sample coffee ward for a panoramic view of Puget Sound from the at the original Starbucks location, and Space Needle’s Observation Deck, glide downtown enjoy the music and antics of street aboard the Seattle Monorail, or play in the waters of the performers. -

2020 Walking Guide

A PERSPECTIVE SHIFT DINO HEDGE A FAMOUS BRIDGE & THE PERFECT GIFT & CUTTING EDGE &A FROSTY BEER RETAIL SHOPPING LOCAL BUSINESSES & INSTITUTIONS BARS AND DINING Brooks Trailhead - Running Store Hello. We’re Les Amis les amis presents an edited selection of cloth- ActivSpace ActivSpace at Fremont provides afford- Infiniti Real Estate and Development Agrodolce Discover the sun-drenched cuisine Marketime Foods Marketime Foods has been Brooks. We make the best running gear on earth. Or ing, artisan jewelry, bags and shoes. International and able workspaces for art, hobby, and business and A full-service brokerage specializing in innovative of Southern Italy & Sicily. This casual, welcoming Fremont’s neighborhood store since 1969. Groceries, any Planet. We believe a run can change a day, a life, the domestic designers such as: Giada Forte, Rachel Comey, offers creative individuals a place to work toward their housing solutions for the greater Seattle area. trattoria features our expertly crafted, handmade Meat, Produce and an expansive selection of Deli Food. world. So come gear up and get on your path to a better Black Crane, and Jerome Dreyfus. 206.632.2877 • dreams. 206.297.8100 • 4020 Leary Way NW • 206.363.3550 • 4258 Fremont Ave N • pasta using the finest organic, sustainable & local We want to be your store! 206.632.8958 • 4416 Fre- self! 206.858.5700 • 3400 Stone Way N • brooks- 3420 Evanston Ave N • lesamis-inc.com F-18 activspace.com P-5 infinitiRED.com T-20 ingredients. 206.547.9707 • 709 N 35th St • mont Ave N • kensmarkets.com V-20 running.com C-28 agrodolcefremont.com EF-20 Liten Liten is a curated boutique filled with delicate arti- BECU A not-for-profit credit union dedicated to improv- Nalanda West A space to explore your mind, and Milstead & Company Is a specialty coffee shop Downtown Dog Lounge Bakery Downtown san jewelry, ceramics and treasures for the home. -

Art Installations

2013 = 3 7/16 if, 6 7/8 if, 10 5/16 if, 13 3/4 if, 17 3/16 if, 20 11/16 of, 23 3/16 2013 = 3 7/16, 3 7/16, 3 7/16, 3 7/16, 3 7/16, 3 1/2, 3 1/2 2013 = Total is 24.1875, = 24 3/16 Folds 2014 Ed FRONT - Adding one more panel - will need to verify with Litho Craft 2014 Version 1 = 3 3/8, 6 3/4, 10 1/8, 13 1/2, 16 7/8, 20 1/4, 23 3/4, 27 1/4 2014 Version 1 = 3 3/8, 3 3/8, 3 3/8, 3 3/8, 3 3/8, 3 3/8, 3 1/2, 3 1/2 2014 Version 1, = total is 27 1/4 2014 Version 2 = 3 7/16, 6 7/8, 10 5/16, 13 3/4, 17 3/16, 20 5/8, 24 1/8, 27 5/8 EVENTS 2014 Version 2 = 3 7/16, 3 7/16, 3 7/16, 3 7/16, 3 7/16, 3 7/16, 3 1/2, 3 1/2 Art Installations 2014 Version 2, = total is 27 5/8 Fremont Sunday Market Every Sunday F Bogart and Bergman Mural - This L The Troll - Hulking beneath the Aurora 1st Friday in Fremont ArtWalk Every month 1st Friday cinematic mural flanks the outdoor movie screen, Bridge squats the Fremont Troll and the Moisture Festival March 19 – April 12 gazing down summer evenings on lounging viewers small snack he snagged before being Hopscotch Beer & Scotch Tasting April 3 & 4, Fri & Sat who bring their own chairs to watch the flickering films turned to stone Solid Ground Annual Fundraising Lunch April 10, Fri R Dinos - Mama and Baby Dinosaurs wandered into Fremont I The Bridge Way Mural - Fremont Arts Council May Day Celebration May 1, Fri and have taken root along the beautiful shores of the Lake Union Beloved by the community, this Mobile Food Rodeo May 3, Sun Ship Canal mural was painted in 1997 and Literacy Source Annual Breakfast May 5, Tue E The Rocket - Our 53’ Cold War era Rocket stands poised for greets drivers as they enter B.F. -

View Entire Book

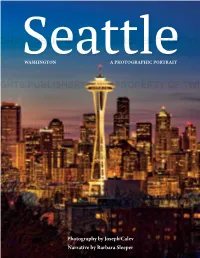

PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS SeattleWASHINGTON A PHOTOGRAPHIC PORTRAIT PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERSPhotography by Joseph PROPERTY Calev OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS Narrative by Barbara Sleeper PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS Seattle WASHINGTON PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERSA PHOTOGRAPHIC PORTRAITPROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERSP hotography by Joseph PROPERTY Calev OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS Narrative by Barbara Sleeper PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS TWI N LIGHTS PUBLISHERS | ROCKPORT, MASSACHUSETTS C opyright © 2020 by Twin Lights Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the copyright owners. All images in this book have been reproduced with the knowledge and prior consent of the artists concerned and no responsibility is accepted by producer, publisher, or printer for any PROPERTYinfringement of copyright or otherwise, OF arising fromTWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWIN LIGHTS PUBLISHERS -

Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2012/December

AL Direct, December 5, 2012 Contents American Libraries Online | ALA News | Booklist Online Seattle Update| Division News| Awards & Grants | Libraries in the News Issues | Tech Talk | E-Content | Books & Reading | Tips & Ideas Great Libraries of the World | Digital Library of the Week | Calendar The e-newsletter of the American Library Association | December 5, 2012 American Libraries Online American Dental Association library may be set to close Maria R. Traska writes: “In July, the American Dental Association’s library budget was slashed, ALA Midwinter Meeting, and eight of 13 library staffers expect to lose Seattle, January 25–29. their jobs January 1 if the board doesn’t Connect and get the reverse action at its December 9–12 board conversations going— meeting. The library cuts sparked a furor over the summer and at the facilitated conversations ADA House of Delegates meeting in October, but the board’s budget and discussion groups, passed without $600,000 for the library. The final budget also award and author events, included a new line of $800,000 to hire a public relations firm.” The Exhibits Opening ADA library was started in 1927 and contains a collection of nearly Reception, Book Buzz 30,000 books and over 600 current journals.... Theater, the ALA-APA American Libraries feature; MLS E-nnounce, Nov. 28, 2007 Networking Reception, speed networking, Dine- Writing for civilians Around, and much more. Laurie L. Putnam writes: “Love to write about libraries? Many of us Stay in touch and get do. For our fellow librarians, we speak volumes, clamoring to fill updates at the Midwinter blogs, association newsletters, and scholarly journals. -

2016-Walking-Guide.Pdf

Center of the Universe ART I NSTALLATIONS Fremont is synonymous with fun; a neighborhood of unexpected and unconven- F Fremont Outdoor Movies - For the last U Late For The Interurban - This statue of tional entertainment. Stand at the center of the 23 years, around dusk on warm Saturday summer J.P. Patches and Gertrude commemorates two of Center of the Universe, visit a Troll who turned to evenings, adventurous people of all ages have come Seattle’s greatest citizens – a couple of clowns – concrete while munching on a Fahrvergnügen, in fun attire to join in this zany Fremont pastime installed in 2008 with their ICU2TV and a dona- gaze upon our Soviet-era Rocket, and shake R Dinos - Mama and Baby Dinosaurs wandered tion tin for Seattle Children’s Hospital a finger with Lenin (Vladimir, that is.) into Fremont and have taken root along the beautiful B The Troll - Hulking beneath the Aurora Bridge squats the Fremont Throughout the year this unique commu- shores of the Lake Union Ship Canal Troll and the small snack he snagged before being turned to stone nity of locally-based shops and distinctive E The Rocket - Our 53’ Cold War era Rocket L The Bridge Way Mural - Beloved by the community, this mural eateries welcomes outlandish events, stands poised for blast- off at Evanston and N 35th was painted in 1997 and greets drivers as they enter Fremont from the including: The Solstice Parade led by the Street, while high above you, the planet Saturn Aurora Bridge painted cyclists, art cars inside the Fremont hovers above its namesake building I B.F.