Rip Currents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Processes and Causes of Shoreline Erosion and Accretion Causes of Shoreline Erosion and Accretion

Coastal Processes and Causes of Shoreline Erosion and Accretion and Accretion Erosion Causes of Shoreline Heather Weitzner, Great Lakes Coastal Processes and Hazards Specialist Photo by Brittney Rogers, New York Sea Grant York Photo by Brittney Rogers, New New York Sea Grant Waves breaking on the eastern Lake Ontario shore. Wayne County Cooperative Extension A shoreline is a dynamic environment that evolves under the effects of both natural 1581 Route 88 North and human influences. Many areas along New York’s shorelines are naturally subject Newark, NY 14513-9739 315.331.8415 to erosion. Although human actions can impact the erosion process, natural coastal processes, such as wind, waves or ice movement are constantly eroding and/or building www.nyseagrant.org up the shoreline. This constant change may seem alarming, but erosion and accretion (build up of sediment) are natural phenomena experienced by the shoreline in a sort of give and take relationship. This relationship is of particular interest due to its impact on human uses and development of the shore. This fact sheet aims to introduce these processes and causes of erosion and accretion that affect New York’s shorelines. Waves New York’s Sea Grant Extension Program Wind-driven waves are a primary source of coastal erosion along the Great provides Equal Program and Lakes shorelines. Factors affecting wave height, period and length include: Equal Employment Opportunities in 1. Fetch: the distance the wind blows over open water association with Cornell Cooperative 2. Length of time the wind blows Extension, U.S. Department 3. Speed of the wind of Agriculture and 4. -

A Quick Guide to Southeast Florida's Coral Reefs

A Quick Guide to Southeast Florida’s Coral Reefs DAVID GILLIAM NATIONAL CORAL REEF INSTITUTE NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY Spring 2013 Prepared by the Land-based Sources of Pollution Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) of the Southeast Florida Coral Reef Initiative (SEFCRI) BRIAN WALKER NATIONAL CORAL REEF INSTITUTE, NOVA SOUTHEASTERN Southeast Florida’s coral-rich communities are more valuable than UNIVERSITY the Spanish treasures that sank nearby. Like the lost treasures, these amazing reefs lie just a few hundred yards off the shores of Martin, Palm Beach, Broward and Miami-Dade Counties where more than one-third of Florida’s 19 million residents live. Fishing, diving, and boating help attract millions of visitors to southeast Florida each year (30 million in 2008/2009). Reef-related expen- ditures generate $5.7 billion annually in income and sales, and support more than 61,000 local jobs. Such immense recreational activity, coupled with the pressures of coastal development, inland agriculture, and robust cruise and commercial shipping industries, threaten the very survival of our reefs. With your help, reefs will be protected from local stresses and future generations will be able to enjoy their beauty and economic benefits. Coral reefs are highly diverse and productive, yet surprisingly fragile, ecosystems. They are built by living creatures that require clean, clear seawater to settle, mature and reproduce. Reefs provide safe havens for spectacular forms of marine life. Unfortunately, reefs are vulnerable to impacts on scales ranging from local and regional to global. Global threats to reefs have increased along with expanding ART SEITZ human populations and industrialization. Now, warming seawater temperatures and changing ocean chemistry from carbon dioxide emitted by the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation are also starting to imperil corals. -

Turning the Tide on Trash: Great Lakes

Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Floating marine debris in Hawaii NOAA PIFSC CRED Educators, parents, students, and Unfortunately, the ocean is currently researchers can use Turning the Tide under considerable pressure. The on Trash as they explore the serious seeming vastness of the ocean has impacts that marine debris can have on prompted people to overestimate its wildlife, the environment, our well being, ability to safely absorb our wastes. For and our economy. too long, we have used these waters as a receptacle for our trash and other Covering nearly three-quarters of the wastes. Integrating the following lessons Earth, the ocean is an extraordinary and background chapters into your resource. The ocean supports fishing curriculum can help to teach students industries and coastal economies, that they can be an important part of the provides recreational opportunities, solution. Many of the lessons can also and serves as a nurturing home for a be modified for science fair projects and multitude of marine plants and wildlife. other learning extensions. C ON T EN T S 1 Acknowledgments & History of Turning the Tide on Trash 2 For Educators and Parents: How to Use This Learning Guide UNIT ONE 5 The Definition, Characteristics, and Sources of Marine Debris 17 Lesson One: Coming to Terms with Marine Debris 20 Lesson Two: Trash Traits 23 Lesson Three: A Degrading Experience 30 Lesson Four: Marine Debris – Data Mining 34 Lesson Five: Waste Inventory 38 Lesson -

Brighton Beach Groynes

CASE STUDY: BRIGHTON BEACH GROYNES BRIGHTON, SOUTH AUSTRALIA FEBRUARY 2017 CLIENT: CITY OF HOLDFAST BAY Adelaide’s beaches are affected by a common phenomenon called ELCOROCK® longshore drift - the flow of water, in one direction, along a beach occurring as a result of winds and currents. In Adelaide longshore drift flows from south to north and it frequently erodes beaches The ELCOROCK system consists of sand- over time, particularly during storm events when tides are high and filled geotextile containers built to form sea is rough. a stabilising, defensive barrier against coastal erosion. Without sand replenishment, the southern end of Adelaide’s beaches will slowly erode and undermine existing infrastructure at The robustness and stability of Elcorock the sea/land interface. The objective of Elcorock sand container geotextile containers provide a solutions groynes, laid perpendicular to the beach, is to capture some of for other marine structures such as groynes and breakwaters. These the natural sand as well as dredged sand, that moves along the structures extend out into the wave zone coast. Over time, this process builds up the beach, particularly and provide marina and beach protection, between the groynes which results in the protection of the existing sand movement control and river training. infrastructure. The size of the container can easily be Geofabrics met with the city of Holdfast Bay in the early stages of selected based on the wave climate and the project to discuss the product, durability and previous projects other conditions ensuring stability under with a similar application. Due to recent weather events, the beach the most extreme conditions. -

Observations of Nearshore Infragravity Waves: Seaward and Shoreward Propagating Components A

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 107, NO. C8, 3095, 10.1029/2001JC000970, 2002 Observations of nearshore infragravity waves: Seaward and shoreward propagating components A. Sheremet,1 R. T. Guza,2 S. Elgar,3 and T. H. C. Herbers4 Received 14 May 2001; revised 5 December 2001; accepted 20 December 2001; published 6 August 2002. [1] The variation of seaward and shoreward infragravity energy fluxes across the shoaling and surf zones of a gently sloping sandy beach is estimated from field observations and related to forcing by groups of sea and swell, dissipation, and shoreline reflection. Data from collocated pressure and velocity sensors deployed between 1 and 6 m water depth are combined, using the assumption of cross-shore propagation, to decompose the infragravity wave field into shoreward and seaward propagating components. Seaward of the surf zone, shoreward propagating infragravity waves are amplified by nonlinear interactions with groups of sea and swell, and the shoreward infragravity energy flux increases in the onshore direction. In the surf zone, nonlinear phase coupling between infragravity waves and groups of sea and swell decreases, as does the shoreward infragravity energy flux, consistent with the cessation of nonlinear forcing and the increased importance of infragravity wave dissipation. Seaward propagating infragravity waves are not phase coupled to incident wave groups, and their energy levels suggest strong infragravity wave reflection near the shoreline. The cross-shore variation of the seaward energy flux is weaker than that of the shoreward flux, resulting in cross-shore variation of the squared infragravity reflection coefficient (ratio of seaward to shoreward energy flux) between about 0.4 and 1.5. -

A Numerical Study of the Long- and Short-Term Temperature Variability and Thermal Circulation in the North Sea

JANUARY 2003 LUYTEN ET AL. 37 A Numerical Study of the Long- and Short-Term Temperature Variability and Thermal Circulation in the North Sea PATRICK J. LUYTEN Management Unit of the Mathematical Models, Brussels, Belgium JOHN E. JONES AND ROGER PROCTOR Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory, Bidston, United Kingdom (Manuscript received 3 January 2001, in ®nal form 4 April 2002) ABSTRACT A three-dimensional numerical study is presented of the seasonal, semimonthly, and tidal-inertial cycles of temperature and density-driven circulation within the North Sea. The simulations are conducted using realistic forcing data and are compared with the 1989 data of the North Sea Project. Sensitivity experiments are performed to test the physical and numerical impact of the heat ¯ux parameterizations, turbulence scheme, and advective transport. Parameterizations of the surface ¯uxes with the Monin±Obukhov similarity theory provide a relaxation mechanism and can partially explain the previously obtained overestimate of the depth mean temperatures in summer. Temperature strati®cation and thermocline depth are reasonably predicted using a variant of the Mellor±Yamada turbulence closure with limiting conditions for turbulence variables. The results question the common view to adopt a tuned background scheme for internal wave mixing. Two mechanisms are discussed that describe the feedback of the turbulence scheme on the surface forcing and the baroclinic circulation, generated at the tidal mixing fronts. First, an increased vertical mixing increases the depth mean temperature in summer through the surface heat ¯ux, with a restoring mechanism acting during autumn. Second, the magnitude and horizontal shear of the density ¯ow are reduced in response to a higher mixing rate. -

Hydrogeology of Near-Shore Submarine Groundwater Discharge

Hydrogeology and Geochemistry of Near-shore Submarine Groundwater Discharge at Flamengo Bay, Ubatuba, Brazil June A. Oberdorfer (San Jose State University) Matthew Charette, Matthew Allen (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) Jonathan B. Martin (University of Florida) and Jaye E. Cable (Louisiana State University) Abstract: Near-shore discharge of fresh groundwater from the fractured granitic rock is strongly controlled by the local geology. Freshwater flows primarily through a zone of weathered granite to a distance of 24 m offshore. In the nearshore environment this weathered granite is covered by about 0.5 m of well-sorted, coarse sands with sea water salinity, with an abrupt transition to much lower salinity once the weathered granite is penetrated. Further offshore, low-permeability marine sediments contained saline porewater, marking the limit of offshore migration of freshwater. Freshwater flux rates based on tidal signal and hydraulic gradient analysis indicate a fresh submarine groundwater discharge of 0.17 to 1.6 m3/d per m of shoreline. Dissolved inorganic nitrogen and silicate were elevated in the porewater relative to seawater, and appeared to be a net source of nutrients to the overlying water column. The major ion concentrations suggest that the freshwater within the aquifer has a short residence time. Major element concentrations do not reflect alteration of the granitic rocks, possibly because the alteration occurred prior to development of the current discharge zones, or from elevated water/rock ratios. Introduction While there has been a growing interest over the last two decades in quantifying the discharge of groundwater to the coastal zone, the majority of studies have been carried out in aquifers consisting of unlithified sediments or in karst environments. -

Part II-1 Water Wave Mechanics

Chapter 1 EM 1110-2-1100 WATER WAVE MECHANICS (Part II) 1 August 2008 (Change 2) Table of Contents Page II-1-1. Introduction ............................................................II-1-1 II-1-2. Regular Waves .........................................................II-1-3 a. Introduction ...........................................................II-1-3 b. Definition of wave parameters .............................................II-1-4 c. Linear wave theory ......................................................II-1-5 (1) Introduction .......................................................II-1-5 (2) Wave celerity, length, and period.......................................II-1-6 (3) The sinusoidal wave profile...........................................II-1-9 (4) Some useful functions ...............................................II-1-9 (5) Local fluid velocities and accelerations .................................II-1-12 (6) Water particle displacements .........................................II-1-13 (7) Subsurface pressure ................................................II-1-21 (8) Group velocity ....................................................II-1-22 (9) Wave energy and power.............................................II-1-26 (10)Summary of linear wave theory.......................................II-1-29 d. Nonlinear wave theories .................................................II-1-30 (1) Introduction ......................................................II-1-30 (2) Stokes finite-amplitude wave theory ...................................II-1-32 -

Rip Current Observations Via Marine Radar

Rip Current Observations via Marine Radar Merrick C. Haller, M.ASCE1; David Honegger2; and Patricio A. Catalan3 Abstract: New remote sensing observations that demonstrate the presence of rip current plumes in X-band radar images are presented. The observations collected on the Outer Banks (Duck, North Carolina) show a regular sequence of low-tide, low-energy, morphologically driven rip currents over a 10-day period. The remote sensing data were corroborated by in situ current measurements that showed depth-averaged rip current velocities were 20e40 cm=s whereas significant wave heights were Hs 5 0:5e1 m. Somewhat surprisingly, these low-energy rips have a surface signature that sometimes extends several surf zone widths from shore and persists for periods of several hours, which is in contrast with recent rip current observations obtained with Lagrangian drifters. These remote sensing observations provide a more synoptic picture of the rip current flow field and allow the identification of several rip events that were not captured by the in situ sensors and times of alongshore deflection of the rip flow outside the surf zone. These data also contain a rip outbreak event where four separate rips were imaged over a 1-km stretch of coast. For potential comparisons of the rip current signature across other radar platforms, an example of a simply calibrated radar image is also given. Finally, in situ observations of the vertical structure of the rip current flow are given, and a threshold offshore wind stress (.0:02 m=s2)isfoundto preclude the rip current imaging. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)WW.1943-5460.0000229. -

Waves and Weather

Waves and Weather 1. Where do waves come from? 2. What storms produce good surfing waves? 3. Where do these storms frequently form? 4. Where are the good areas for receiving swells? Where do waves come from? ==> Wind! Any two fluids (with different density) moving at different speeds can produce waves. In our case, air is one fluid and the water is the other. • Start with perfectly glassy conditions (no waves) and no wind. • As wind starts, will first get very small capillary waves (ripples). • Once ripples form, now wind can push against the surface and waves can grow faster. Within Wave Source Region: - all wavelengths and heights mixed together - looks like washing machine ("Victory at Sea") But this is what we want our surfing waves to look like: How do we get from this To this ???? DISPERSION !! In deep water, wave speed (celerity) c= gT/2π Long period waves travel faster. Short period waves travel slower Waves begin to separate as they move away from generation area ===> This is Dispersion How Big Will the Waves Get? Height and Period of waves depends primarily on: - Wind speed - Duration (how long the wind blows over the waves) - Fetch (distance that wind blows over the waves) "SMB" Tables How Big Will the Waves Get? Assume Duration = 24 hours Fetch Length = 500 miles Significant Significant Wind Speed Wave Height Wave Period 10 mph 2 ft 3.5 sec 20 mph 6 ft 5.5 sec 30 mph 12 ft 7.5 sec 40 mph 19 ft 10.0 sec 50 mph 27 ft 11.5 sec 60 mph 35 ft 13.0 sec Wave height will decay as waves move away from source region!!! Map of Mean Wind -

Mapping Turbidity Currents Using Seismic Oceanography Title Page Abstract Introduction 1 2 E

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Ocean Sci. Discuss., 8, 1803–1818, 2011 www.ocean-sci-discuss.net/8/1803/2011/ Ocean Science doi:10.5194/osd-8-1803-2011 Discussions OSD © Author(s) 2011. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 8, 1803–1818, 2011 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Ocean Science (OS). Mapping turbidity Please refer to the corresponding final paper in OS if available. currents using seismic E. A. Vsemirnova and R. W. Hobbs Mapping turbidity currents using seismic oceanography Title Page Abstract Introduction 1 2 E. A. Vsemirnova and R. W. Hobbs Conclusions References 1Geospatial Research Ltd, Department of Earth Sciences, Tables Figures Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, UK 2Department of Earth Sciences, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, UK J I Received: 25 May 2011 – Accepted: 12 August 2011 – Published: 18 August 2011 J I Correspondence to: R. W. Hobbs ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 1803 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract OSD Using a combination of seismic oceanographic and physical oceanographic data ac- quired across the Faroe-Shetland Channel we present evidence of a turbidity current 8, 1803–1818, 2011 that transports suspended sediment along the western boundary of the Channel. We 5 focus on reflections observed on seismic data close to the sea-bed on the Faroese Mapping turbidity side of the Channel below 900m. Forward modelling based on independent physi- currents using cal oceanographic data show that thermohaline structure does not explain these near seismic sea-bed reflections but they are consistent with optical backscatter data, dry matter concentrations from water samples and from seabed sediment traps. -

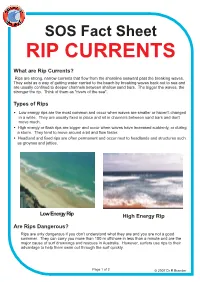

What Are Rip Currents? Types of Rips Are Rips Dangerous

What are Rip Currents? Rips are strong, narrow currents that flow from the shoreline seaward past the breaking waves. They exist as a way of getting water carried to the beach by breaking waves back out to sea and are usually confined to deeper channels between shallow sand bars. The bigger the waves, the stronger the rip. Think of them as "rivers of the sea". Types of Rips • Low energy rips are the most common and occur when waves are smaller or haven't changed in a while. They are usually fixed in place and sit in channels between sand bars and don't move much. • High energy or flash rips are bigger and occur when waves have increased suddenly, or during a storm. They tend to move around a bit and flow faster. • Headland and fixed rips are often permanent and occur next to headlands and structures such as groynes and jetties. Low Energy Rip High Energy Rip Are Rips Dangerous? Rips are only dangerous if you don't understand what they are and you are not a good swimmer. They can carry you more than 100 m offshore in less than a minute and are the major cause of surf drownings and rescues in Australia. However, surfers use rips to their advantage to help them swim out through the surf quickly. Page1of2 © 2007 Dr R Brander continued Spotting a Rip Since rips often sit in deeper channels between shallow sand bars, always spend 5-10 minutes looking at the surf zone for consistent darker and "calmer" areas of water that extend offshore between the breaking waves.