Chapter 13B BUILDING an ALL-BAND HF RECEIVER (Continued)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RF & Microwave Components & Systems Catalog

There is a new leader and source for your RF & microwave systems and components … Spectrum Microwave. Combining the people, products and technologies from FSY Microwave, Salisbury Engineering, Q-Bit, Magnum Microwave, Radian Technologies and Amplifonix into a single organization poised to provide a wide range of microwave solutions. Spectrum Microwave offers a worldwide network of sales, distribution and manufacturing locations that gives us a responsive local presence in North America, Europe and Asia. We’ve assembled an experienced engineering team that will help you select the right standard product or design a custom solution for your specific application. Our expanded product line now ranges from sophisticated microwave systems and integrated assemblies to advanced control components to ceramic filters and antennas. This diverse array of products includes technologies to satisfy both low cost commercial and high performance military applications. 2 rf microwave& components and systems Index Page Introduction Product Selection Guide . .5-9 Design & Testing . .10-11 RF & Microwave Solutions Development . .12-13 • Lumped element and cavity filters Cascade . .14-15 Specwave.com . .16 • BTS filters and tower mounted amplifiers About Spectrum Control . .17 • Waveguide and tubular filters • Ceramic bandpass filters and duplexers Frequency Control Components • Patch antenna elements and assemblies Amplifiers . .19-20 Mixers . .21-22 Voltage Controlled Oscillators (VCOs) . .23 Dielectric Resonator Oscillators (DROs) . .24 Attenuators, Detectors & Switches . .25-26 Coaxial Ceramic Resonators . .27-28 Custom Microwave Filters Filter Topology Selection . .30-33 Filter Considerations . .34 Frequency Ranges . .35 Lumped Element Filters . .36-38 Cavity Filters . .39-41 Waveguide Filters . .42-43 Tubular Filters . .44-45 Suspended Substrate Filters . -

Mfj-1046 Passive Preselector

MFJ-1046 Instruction Manual Passive Preselector MFJ-1046 PASSIVE PRESELECTOR Introduction The MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector is designed to reduce receive overload from strong out of band signals. It contains selective circuits that cover 1.6 to 33 MHz in six steps, providing the greatest selectivity on the lowest frequencies where overload is most common. The MFJ-1046 has two rear panel SO-239 connectors for RF connections and a bypass switch to take the unit in and out of the circuit. Installation Connect the MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector between your antenna and receiver as shown in Figure 1. The Radio connector goes directly to the receiver with a short well shielded lead; the Antenna connector goes to the antenna. Figure 1 WARNING: NEVER connect an amplifier or transmitter to the MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector. Failure to follow this warning may cause MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector or other equipment to be damaged. 1 MFJ-1046 Instruction Manual Passive Preselector Operation With the MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector properly connected, simply turn the Band switch to the desired band and adjust the Tune control for maximum signal level. With the Bypass switch depressed, the MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector becomes active. Adjust the Tune control for maximum signal level. The maximum loss on the desired amateur band is less than 5dB if the correct frequency range is selected. Note: Always use the highest frequency band range that covers the desired band for minimum loss. Typical frequency response is shown in Figure 2. A: Transmission Loss Figure 2 2 MFJ-1046 Instruction Manual Passive Preselector Technical Assistance If you have any problem with this unit first check the appropriate section of this manual. -

MFJ-1048 PASSIVE PRESELECTOR Introduction

MFJ-1048 Instruction Manual Passive Preselector MFJ-1048 PASSIVE PRESELECTOR Introduction The MFJ-1048 Passive Preselector is designed to reduce receive overload from strong out of band signals. It contains selective circuits that cover 1.6 to 33 MHz in six steps, providing the greatest selectivity on the lowest frequencies where overload is most common. The MFJ-1048 also features internal transmit-receive switching with adjustable time delay. A rear panel jack is available for an external control that will switch the MFJ-1048 into a bypass mode (we strongly recommend using the external control line for switching to avoid pull in timing errors). The MFJ-1048 has two rear panel SO-239 connectors for RF connections and a standard 2.1mm power receptacle for 10 to 16 volt DC voltage. If DC voltage is not applied, the MFJ-1048 will remain in a bypass mode. Installation Connect the MFJ-1048 Passive Preselector between your antenna and receiver or transceiver antenna connector as shown in Figure 1. The Radio connector goes directly to the transceiver or receiver with a short well shielded lead; the Antenna connector goes to the antenna through any amplifier, TVI filter, or any other station equipment. Figure 1 WARNING: NEVER connect an amplifier or radio with more than 200 watts output to the MFJ-1048 Passive Preselector. NEVER use an internal antenna tuner to correct for high SWR if the tuner is in the radio or on the radio side of the MFJ-1048 Passive Preselector. Failure to follow this warning may allow your MFJ- 1048 Passive Preselector or other equipment to be damaged. -

Time and Frequency Users' Manual

,>'.)*• r>rJfl HKra mitt* >\ « i If I * I IT I . Ip I * .aference nbs Publi- cations / % ^m \ NBS TECHNICAL NOTE 695 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE/National Bureau of Standards Time and Frequency Users' Manual 100 .U5753 No. 695 1977 NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS 1 The National Bureau of Standards was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, a technical (3) basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to pro- mote public safety. The Bureau consists of the Institute for Basic Standards, the Institute for Materials Research the Institute for Applied Technology, the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology, the Office for Information Programs, and the Office of Experimental Technology Incentives Program. THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS provides the central basis within the United States of a complete and consist- ent system of physical measurement; coordinates that system with measurement systems of other nations; and furnishes essen- tial services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. The Institute consists of the Office of Measurement Services, and the following center and divisions: Applied Mathematics -

Variable Capacitors in RF Circuits

Source: Secrets of RF Circuit Design 1 CHAPTER Introduction to RF electronics Radio-frequency (RF) electronics differ from other electronics because the higher frequencies make some circuit operation a little hard to understand. Stray capacitance and stray inductance afflict these circuits. Stray capacitance is the capacitance that exists between conductors of the circuit, between conductors or components and ground, or between components. Stray inductance is the normal in- ductance of the conductors that connect components, as well as internal component inductances. These stray parameters are not usually important at dc and low ac frequencies, but as the frequency increases, they become a much larger proportion of the total. In some older very high frequency (VHF) TV tuners and VHF communi- cations receiver front ends, the stray capacitances were sufficiently large to tune the circuits, so no actual discrete tuning capacitors were needed. Also, skin effect exists at RF. The term skin effect refers to the fact that ac flows only on the outside portion of the conductor, while dc flows through the entire con- ductor. As frequency increases, skin effect produces a smaller zone of conduction and a correspondingly higher value of ac resistance compared with dc resistance. Another problem with RF circuits is that the signals find it easier to radiate both from the circuit and within the circuit. Thus, coupling effects between elements of the circuit, between the circuit and its environment, and from the environment to the circuit become a lot more critical at RF. Interference and other strange effects are found at RF that are missing in dc circuits and are negligible in most low- frequency ac circuits. -

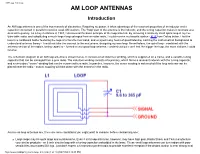

AM Loop Antennas AM LOOP ANTENNAS Introduction

AM Loop Antennas AM LOOP ANTENNAS Introduction An AM loop antenna is one of the true marvels of electronics. Requiring no power, it takes advantage of the resonant properties of an inductor and a capacitor connected in parallel to receive weak AM stations. The "loop" part of the antenna is the inductor, and the tuning capacitor makes it resonate at a desired frequency. As a boy in Abilene in 1967, I discovered the basic principle of the loop antenna. By removing a relatively small spiral loop in my five tube table radio, and substituting a much larger loop salvaged from an older radio, I could receive my favorite station - KLIF from Dallas better. I hid the loop in a cardboard holder featuring the logo of a favorite rock band, and enjoyed many hours of good listening. Lacking the mathematical background to understand antenna theory - I could not take the concept to the next phase: designing my own loop. Nevertheless, the spiral loop - combined with the antenna section of the radio's tuning capacitor - formed a very good loop antenna. I understood quite well that the bigger the loop, the more stations I could receive. The schematic diagram of an AM loop antenna is shown below. It consists of an inductive winding, which is supported on a frame, and a variable tuning capacitor that can be salvaged from a junk radio. The inductive winding consists of a primary, which forms a resonant network with the tuning capacitor, and a secondary "sense" winding that can be connected to a radio. In practice, however, the sense winding is not needed if the loop antenna can be placed near the radio - mutual coupling will take place with the antenna in the radio. -

Keysight Technologies Spectrum Analysis Basics

Keysight Technologies Spectrum Analysis Basics Application Note 150 Keysight Technologies. Inc. dedicates this application note to Blake Peterson. Blake’s outstanding service in technical support reached customers in all corners of the world during and after his 45-year career with Hewlett-Packard and Keysight. For many years, Blake trained new marketing and sales engineers in the “ABCs” of spectrum analyzer technology, which provided the basis for understanding more advanced technology. He is warmly regarded as a mentor and technical contributor in spectrum analysis. Blake’s many accomplishments include: –Authored the original edition of the Spectrum Analysis Basics application note and contributed to subsequent editions –Helped launch the 8566/68 spectrum analyzers, marking the beginning of modern spectrum analysis, and the PSA Series spectrum analyzers that set new performance benchmarks in the industry when they were introduced –Inspired the creation of Blake Peterson University––required training for all engineering hires at Keysight As a testament to his accomplishments and contributions, Blake was honored with Microwaves & RF magazine’s irst Living Legend Award in 2013. 2 Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Introduction ................................................................................................................ 5 Frequency domain versus time domain ....................................................................................... 5 What is a spectrum? ..................................................................................................................... -

Homework #6 Solution Set

Homework #6 Solution Set (32 points - 1 per problem) 1. List the five steps in the process of receiving a radio signal. a) Acquisition of the radio signal b) Selection of the appropriate carrier c) Amplification of the selected RF signal d) Recovery of the information (Detection) e) Processing the recovered information signal 2. In the crystal radio receiver of figure 5-2, which of the five steps are being performed? D1 Long Wire Antenna IN60 - Germanium L1 C1 Tuning Coil - 250 uH 30 - 365 pF - Tuning High Impedance Headphones Earth Ground [Figure 5-2] The following steps are being performed: Acquisition (Long-wire antenna), Selection (Tuned circuit with L1 and C1), Detection (D1), and Processing of the recovered information signal (Headphones). 3. Why is RF amplification needed in a radio receiver? RF amplification is needed because the input signals at the antenna are of extremely low voltage and power; much too low to be directly processed without amplification. 4. How is a variable capacitor used in the tuning mechanism of a receiver? A variable capacitor is used with an inductor to form a variable-frequency bandpass filter. This filter is tuned to the frequency of the desired carrier signal. 5. A certain TRF radio receiver uses a variable capacitor with a range of 40 pF to 300 pF in combination with a fixed inductor of 200 mH. What is the tuning range of this receiver? To solve this problem, the resonance formula is used twice: 1 1 f min = = = 649.75KHz 2p LCmax 2p (200mH )(300 pF) 1 1 f max = = = 1779.41KHz 2p LCmin 2p (200mH )(40 pF) 6. -

2706 RF Preselector Instruction Manual

Instruction Manual 2706 RF Preselector 070-8545-02 Warning The servicing instructions are for use by qualified personnel only. To avoid personal injury, do not perform any servicing unless you are qualified to do so. Refer to all safety summaries prior to performing service. www.tektronix.com Copyright © Tektronix, Inc. All rights reserved. Tektronix products are covered by U.S. and foreign patents, issued and pending. Information in this publication supercedes that in all previously published material. Specifications and price change privileges reserved. Tektronix, Inc., P.O. Box 500, Beaverton, OR 97077 TEKTRONIX and TEK are registered trademarks of Tektronix, Inc. WARRANTY Tektronix warrants that this product will be free from defects in materials and workmanship for a period of one (1) year from the date of shipment. If any such product proves defective during this warranty period, Tektronix, at its option, either will repair the defective product without charge for parts and labor, or will provide a replacement in exchange for the defective product. In order to obtain service under this warranty, Customer must notify Tektronix of the defect before the expiration of the warranty period and make suitable arrangements for the performance of service. Customer shall be responsible for packaging and shipping the defective product to the service center designated by Tektronix, with shipping charges prepaid. Tektronix shall pay for the return of the product to Customer if the shipment is to a location within the country in which the Tektronix service center is located. Customer shall be responsible for paying all shipping charges, duties, taxes, and any other charges for products returned to any other locations. -

RF Front-End World Class Designs

RF Front-End World Class Designs Janine Sullivan Love with Cheryl Ajluni John Blyler Christopher Bowick Joe Carr Farid Dowla Michael Finneran Andrei Grebennikov Ian Hickman Leo G. Maloratsky Ian Poole Nathan O. Sokal Steve Winder HankZumbahlen AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Newnes is an imprint of Elsevier Newnes Contents Preface xi About the Editor xiii About the Contributors xv Chapter 1: Radio Waves and Propagation 1 1.1 Electric Fields 1 1.2 Magnetic Fields 3 1.3 Radio Waves 3 1.4 Frequency to Wavelength Conversion 5 1.5 Radio Spectrum 6 1.6 Polarization 7 1.7 How Radio Signals Travel 9 1.8 Refraction, Reflection and Diffraction 10 1.9 Reflected Signals 12 1.10 Layers above the Earth 13 1.11 Ground Wave 17 1.12 Skywaves 18 1.13 Distances and the Angle of Radiation 21 1.14 Multiple Reflections 22 1.15 Critical Frequency 23 1.16 MUF 23 1.17 LUF 24 1.18 Skip Zone 24 1.19 State of the Ionosphere 24 1.20 Fading 25 1.21 Ionospheric Disturbances 26 1.22 Very Low Frequency Propagation 27 1.23 VHF and Above 28 1.24 Greater Distances 28 vi Contents 1.25 Troposcatter 29 1.26 Sporadic E 30 1.27 Meteor Scatter 31 1.28 Frequencies above 3 GHz 32 Chapter 2: RF Front-End Design 33 2.1 Higher Levels of Integration 34 2.2 Basic Receiver Architectures 36 2.3 ADC'S Effect on Front-end Design 57 2.4 Software Defined Radios 58 2.5 Case Study—Modern Communication Receiver 59 Chapter 3: Radio Transmission Fundamentals for WLANs 65 3.1 Defining Transmission Capacity -

Time and Frequency Users' Manual

1 United States Department of Commerce 1 j National Institute of Standards and Technology NAT L. INST. OF STAND & TECH R.I.C. NIST PUBLICATIONS I A111D3 MSDD3M NIST Special Publication 559 (Revised 1990) Time and Frequency Users Manual George Kamas Michael A. Lombardi NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS & TECHNOLOGY Research Information Center Gakhersburg, MD 20699 NIST Special Publication 559 (Revised 1990) Time and Frequency Users Manual George Kamas Michael A. Lombardi Time and Frequency Division Center for Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics National Measurement Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Boulder, Colorado 80303-3328 (Supersedes NBS Special Publication 559 dated November 1979) September 1990 U.S. Department of Commerce Robert A. Mosbacher, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology John W. Lyons, Director National Institute of Standards U.S. Government Printing Office For sale by the Superintendent and Technology Washington: 1990 of Documents Special Publication 559 (Rev. 1990) U.S. Government Printing Office Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Washington, DC 20402 Spec. Publ. 559 (Rev. 1990) 160 pages (Sept. 1990) CODEN: NSPUE2 ABSTRACT This book is for the person who needs information about making time and frequency measurements. It is written at a level that will satisfy those with a casual interest as well as laboratory engineers and technicians who use time and frequency every day. It includes a brief discussion of time scales, discusses the roles of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and other national laboratories, and explains how time and frequency are internationally coordinated. It also describes the available time and frequency services and how to use them. -

New Concepts in Front End Design for Receivers with Large, Multiband Tuning Ranges

New Concepts in Front End Design for Receivers with Large, Multiband Tuning Ranges S. M. Shajedul Hasan Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering Committee Members: Dr. Steven W. Ellingson, Chair Dr. R. Michael Buehrer Dr. Jeffrey H. Reed Dr. William A. Davis Dr. John H. Simonetti April 3, 2009 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: RF Multiplexer, Multiband Multimode Radio, Public Safety Radio, Wideband Receiver Copyright 2009, S. M. Shajedul Hasan New Concepts in Front End Design for Receivers with Large, Multiband Tuning Ranges S. M. Shajedul Hasan Abstract This dissertation presents new concepts in front end design for receivers with large, multiband tuning ranges. Such receivers are required to support large bandwidths (up to 10’s of MHz) over very large tuning ranges (30:1 and beyond) with antennas that are usually narrowband, or which at best support multiple narrow bandwidths. Traditional techniques to integrate a single antenna with such receivers are limited in their ability to handle simultaneous channels distributed over very large tuning ranges, which is important for frequency-agile cognitive radio, surveillance, and other applications requiring wideband or multiband monitoring. Direct conversion architecture is gaining popularity due to the recent advancements in CMOS–based RFIC technology. The possibility of multiple parallel transceivers in RF CMOS suggests an approach to antenna–receiver integration using multiplexers. This dissertation describes an improved use of multiplexers to integrate anten- nas to receivers. First, the notion of sensitivity–constrained design is considered.