Use of a Rock As an Anvil for Breaking Scallops by the Yellowhead Wrasse, Halichoeres Garnoti (Labridae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Megan E

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School November 2017 Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Megan E. Hepner University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Other Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Hepner, Megan E., "Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7408 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary by Megan E. Hepner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Marine Science with a concentration in Marine Resource Assessment College of Marine Science University of South Florida Major Professor: Frank Muller-Karger, Ph.D. Christopher Stallings, Ph.D. Steve Gittings, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 31st, 2017 Keywords: Species richness, biodiversity, functional diversity, species traits Copyright © 2017, Megan E. Hepner ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to my major advisor, Dr. Frank Muller-Karger, who provided opportunities for me to strengthen my skills as a researcher on research cruises, dive surveys, and in the laboratory, and as a communicator through oral and presentations at conferences, and for encouraging my participation as a full team member in various meetings of the Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (MBON) and other science meetings. -

Sharkcam Fishes

SharkCam Fishes A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower By Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie 1 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index Trevor Mendelow, designer of SharkCam, on August 31, 2014, the day of the original SharkCam installation. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition by Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. For questions related to this guide or its usage contact Erin Burge. The suggested citation for this guide is: Burge EJ, CE O’Brien and jon-newbie. 2020. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition. Los Angeles: Explore.org Ocean Frontiers. 201 pp. Available online http://explore.org/live-cams/player/shark-cam. Guide version 5.0. 24 February 2020. 2 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index TABLE OF CONTENTS SILVERY FISHES (23) ........................... 47 African Pompano ......................................... 48 FOREWORD AND INTRODUCTION .............. 6 Crevalle Jack ................................................. 49 IDENTIFICATION IMAGES ...................... 10 Permit .......................................................... 50 Sharks and Rays ........................................ 10 Almaco Jack ................................................. 51 Illustrations of SharkCam -

Sharkcam Fishes a Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower by Erin J

SharkCam Fishes A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower By Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie 1 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Information Index Trevor Mendelow, designer of SharkCam, on August 31, 2014, the day of the original SharkCam installation SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 3rd edition by Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. For questions related to this guide or its usage contact Erin Burge. The suggested citation for this guide is: Burge EJ, CE O’Brien and jon-newbie. 2018. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 3rd edition. Los Angeles: Explore.org Ocean Frontiers. 169 pp. Available online http://explore.org/live-cams/player/shark-cam. Guide version 3.0. 26 January 2018. 2 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Information Index TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD AND INTRODUCTION.................................................................................. 8 IDENTIFICATION IMAGES .......................................................................................... 11 Sharks and Rays ................................................................................................................................... 11 Table: Relative frequency of occurrence and relative size .................................................................... -

Andrew David Dorka Cobián Rojas Felicia Drummond Alain García Rodríguez

CUBA’S MESOPHOTIC CORAL REEFS Fish Photo Identification Guide ANDREW DAVID DORKA COBIÁN ROJAS FELICIA DRUMMOND ALAIN GARCÍA RODRÍGUEZ Edited by: John K. Reed Stephanie Farrington CUBA’S MESOPHOTIC CORAL REEFS Fish Photo Identification Guide ANDREW DAVID DORKA COBIÁN ROJAS FELICIA DRUMMOND ALAIN GARCÍA RODRÍGUEZ Edited by: John K. Reed Stephanie Farrington ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research was supported by the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research under award number NA14OAR4320260 to the Cooperative Institute for Ocean Exploration, Research and Technology (CIOERT) at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute-Florida Atlantic University (HBOI-FAU), and by the NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory under award number NA150AR4320064 to the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS) at the University of Miami. This expedition was conducted in support of the Joint Statement between the United States of America and the Republic of Cuba on Cooperation on Environmental Protection (November 24, 2015) and the Memorandum of Understanding between the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. National Park Service, and Cuba’s National Center for Protected Areas. We give special thanks to Carlos Díaz Maza (Director of the National Center of Protected Areas) and Ulises Fernández Gomez (International Relations Officer, Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment; CITMA) for assistance in securing the necessary permits to conduct the expedition and for their tremendous hospitality and logistical support in Cuba. We thank the Captain and crew of the University of Miami R/V F.G. Walton Smith and ROV operators Lance Horn and Jason White, University of North Carolina at Wilmington (UNCW-CIOERT), Undersea Vehicle Program for their excellent work at sea during the expedition. -

Halichoeres Bivittatus (Bloch, 1791) Frequent Synonyms / Misidentifications: None / Halichoeres Maculipinna (Müller and Troschel, 1848)

click for previous page 1710 Bony Fishes Halichoeres bivittatus (Bloch, 1791) Frequent synonyms / misidentifications: None / Halichoeres maculipinna (Müller and Troschel, 1848). FAO names: En - Slippery dick. Diagnostic characters: Body slender, depth 3.3 to 4.6 in standard length.Head rounded and scaleless;snout blunt; 1 pair of enlarged canine teeth at front of upper jaw and a small canine posteriorly near corner of mouth; 2 pairs of enlarged canine teeth anteriorly in lower jaw. Gill rakers on first arch 16 to 19. Dorsal fin continu- ous, with 9 spines and 11 soft rays;anal fin with 3 spines and 9 soft rays;caudal fin rounded;pectoral-fin rays 13. Lateral line continuous with an abrupt downward bend beneath soft portion of dorsal fin, and 27 pored scales. Colour: body colour variable, primarily pale green to white ground colour with a dark midbody stripe, a second lower stripe often present but less distinct; small green and yellow bicoloured spot above pectoral fin; pinkish or orange markings on the head, these sometimes outlined with pale blue; in adults, the tips of the cau- dal-fin lobes are black. Size: Maximum length to about 20 cm. Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Inhabits a di- versity of habitats from coral reef to rocky reef and seagrass beds. Any disturbance of the bot- tom, such as the overturning of a rock will attract a swarm of them, all hoping to find food uncov- ered. Feeds omnivorously on crabs, fishes, sea urchins, polychaetes, molluscs, and brittle stars. This species is not marketed for food, but is com- monly seen in the aquarium trade. -

Experiential Training in Florida and the Florida Keys. a Pretrip Training Manual

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 341 547 SE 052 352 AUTHOR Baker, Claude D., Comp.; And Others TITLE Experiential Training in Florida and the Florida Keys. A Pretrip Training Manual. PUB DATE May 91 NOTE 82p.; For field trip guidelines, see ED 327 394. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Animals; Classification; *Ecology; Environmental Education; Estuaries; *Field Trips; Higher Educatioa; Ichthyology; *Marine Biology; Plant Identification; Plants (Botany); *Resource Materials; Science Activities; Science Education; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS Coral Reefs; Dichotomous Keys; *Florida ABSTRACT This document is a pretrip instruction manual that can be used by secondary school and college teachers who are planning trips to visit the tropical habitats in South Florida. The material is divided into two parts:(1) several fact sheets on the various habitats in South Florida; and (2) a number of species lists for various areas. Factsheets on the classification of marine environments, the zones of the seashore, estuaries, mangroves, seagrass meadows, salt marshes, and coral reefs are included. The species lists included algae, higher plants, sponges, worms, mollusks, bryozoans, arthropods, echinoderms, vertebrates,I insects, and other invertebrates. The scientific name, common name, and a brief description are supplied for all species. Activities on the behavior and social life of fish, a dichotomous key for seashells, and a section that lists -

Baseline Multispecies Coral Reef Fish Stock Assessment for the Dry Tortugas

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-487 Baseline Multispecies Coral Reef Fish Stock Assessment for the Dry Tortugas Jerald S. Ault, Steven G. Smith, Geoffrey A. Meester, Jiangang Luo, James A. Bohnsack, and Steven L. Miller U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center 75 Virginia Beach Drive Miami, Florida 33149 August 2002 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-487 Baseline Multispecies Coral Reef Fish Stock Assessment for the Dry Tortugas Jerald S. Ault 1, Steven G. Smith 1, Geoffrey A. Meester 1, Jiangang Luo 1, James A. Bohnsack 2 , and Steven L. Miller3 with significant contributions by Douglas E. Harper2, Dione W. Swanson3, Mark Chiappone3, Erik C. Franklin1, David B. McClellan2, Peter Fischel2, and Thomas W. Schmidt4 _____________________________ U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Donald L. Evans, Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Conrad C. Lautenbacher, Jr., Under Secretary for Oceans and Atmosphere National Marine Fisheries Service William T. Hogarth, Assistant Administrator for Fisheries August 2002 This technical memorandum series is used for documentation and timely communication of preliminary results, interim reports, or special purpose information. Although the memoranda are not subject to complete formal review, editorial control, or detailed editing, they are expected to reflect sound professional work. 1 University of Miami, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Miami, FL 2 NOAA/Fisheries Southeast Fisheries Science Center, Miami, FL 3 National Undersea Research Center, Key Largo, FL 4 National Park Service, Homestead, FL NOTICE The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) does not approve, recommend, or endorse any proprietary product or material mentioned in this publication. -

2015 Steneck Et Al Status and Trends Of

Status and Trends of Bonaire’s Reefs in 2015: Slow but steady signs of resilience Project Directors: Robert S. Steneck1 Suzanne N. Arnold2 3 Ramón de Leó n Douglas B. Rasher1 1University of Maine, School of Marine Sciences 2The Island Institute 3Reef Support B.V. Kaya Oro 33. Bonaire. Dutch Caribbean 1 Table of Contents and Contributing Authors Pages Executive Summary: Status and Trends of Bonaire’s Reefs in 2015: Slow but steady signs of resilience Robert S. Steneck, Suzanne N. Arnold, R. Ramón de León, Douglas B. Rasher 3 - 13 Results for Bonaire 2015 (parentheses indicates 1st page of the chapter’s appendix) Chapter 1: Patterns and trends in corals, seaweeds Robert S. Steneck…………………………………………………( 95). 14 - 22 Chapter 2: Trends in Bonaire’s herbivorous fish: change over time Suzanne N. Arnold……………………………………….…( 96 & 99). 23 - 31 Chapter 3: Status and trends in sea urchins Diadema and Echinometra Kaitlyn Boyle ………………………………………………….…(100). 32 - 41 Chapter 4: Patterns of predatory fish biomass and density within and around Fish Protection Areas of the Bonaire Marine Park Ruleo Camacho………………………………………...….(101 & 112). 42 - 57 Chapter 5: Juvenile Corals Keri Feehan ….……………………………………………………(114). 58 – 65 Chapter 6: Architectural complexity of Bonaire’s coral reefs Margaret W. Wilson….……………………………………..…….(115). 66 – 71 Chapter 7: Fish bite rates of herbivorous fishes Emily Chandler and Douglas B. Rasher……….…………….……(117). 72 - 81 Chapter 8: Disease of juvenile fishes Martin de Graaf and Fernando Simal……….…………………..…(119). 82- 89 Chapter 9: Damselfish density and abundance: distribution and predator impacts Bob Wagner and Robert S. Steneck ………………………………(120). 90 - 93 2 Executive Summary: Status and Trends of Bonaire’s Reefs in 2015: Slow but steady signs of resilience Robert S. -

Download the Full List of Species Name Changes For

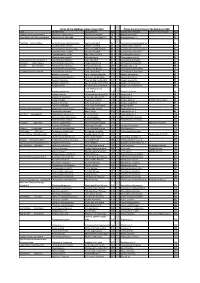

Fishes of the Maldives Indian Ocean 2014 Photo Guide to Fishes of the Maldives 1998 Family Scientific Name Common Name Page Scientific Name Changed Common Name Changed Page Solderfishes Holocentridae-2 Myripristis melanosticta Splendid Soldierfish 78 Myripristis botche 47 Ghost Pipefishes Solenostomidae Solenostomus halimeda Coralline Ghost Pipefish 81 Solenostome sp. 1 50 Pipefishes Syngnathidae Corythoichthys haematopterus Reef-top Pipefish 82 Corythoichtys haematopterus* 51 Corythoichthys schultzi Schultz’s Pipefish 83 Corythoichtys schultzi* 51 Corythoichthys flavofasciatus Yellow-banded Pipefish 83 Corythoichtys flavofasciatus* 51 Corythoichthys insularis Cheeked Pipefish 83 Corythoichtys insularis* 51 Doryrhamphus excisus Blue-stripe Pipefish 84 Doryrhamphus exicus* 53 Hippocampus jayakari Spiny Seahorse 85 Hippocampus hystrix 53 Scorpionfishes Scorpaenidae-2 Scorpaenopsis diabolus False Stonefish 89 Scorpaenopsis diabola 57 Groupers Serranidae-2 Cephalopholis leopardus Leopard Rock Cod 98 Cephalopholis leoparda 66 Basslets Serranidae-3 Pseudanthias lunulatus Yellow-eye Basslet 107 Pseudanthias n. sp. 74 Pseudanthias bimarginatus Short-snout Basslet 109 Pseudanthias parvirostris 76 Cardinalfishes Apogonidae Cheilodipterus lineatus Tiger Cardinalfish 114 Cheilodipterus macrodon 81 Apogon urostigma Spiny-head Cardinalfish 117 Apogon kallopterus 83 Apogon melanorhynchus Spiny-eye Cardinalfish 117 Apogon fraenatus 84 Apogon fraenatus Tapered-line Cardinalfish 117 Apogon exostigma 84 Apogon savayensis Big-eye Dusky-cardinalfish 118 Apogon -

Sustainabilitiy of the Marine Ornamental Fishery in Puerto Rico: Ecological Aspects

SUSTAINABILITIY OF THE MARINE ORNAMENTAL FISHERY IN PUERTO RICO: ECOLOGICAL ASPECTS Final Report Antares Ramos Álvarez Award number: NA09NMF4630126 Submitted: 27/December/11 INTRODUCTION The trade of ornamental fisheries has existed in Puerto Rico (PR) since the 1960’s (Sadovi 1991, Ojeda 2002, Mote 2002, Matos-Caraballo & Mercado-Porrata 2006). Ornamental fisheries were originally started by foreign surfers looking for a way to gain an income during the surfing off-season, giving them a means to stay on the island. It is a trade that remained unregulated until the 1998 Fisheries Law of Puerto Rico (Law 278) and its Fisheries Regulation 6768 of 2004 were passed. The new fishing law requests that ornamental fishermen acquire a fishing permit so that they can both capture and export ornamental species, in addition to the commercial fisherman license. Regulation 6768 establishes the commercial fishermen license fee to $40 with duration of four years, the capture permit fee to $100, and the export permit fee to $400 both with duration of one year. Appendix 4 of Regulation 6768 limits the list of permitted exported species to 20 fish species and 8 invertebrate species (see Appendix 1 for list), compared to over 100 species that were previously exported (Sadovy 1991, Ojeda 2002). The limitation of permitted species took place due to a perceived fear of resource abuse (Mote 2002). These changes in legislation intensified the already existing friction between fishermen and regulation authorities in PR. Fishermen were not properly consulted during any part of the process (LeGore & Hardin 2005); they were informed about the new changes once the law was passed. -

Fungal Microbiomes Are Determined by Host Phylogeny and Exhibit Widespread Associations with the Bacterial

642 Fungal microbiomes are determined by host phylogeny and exhibit widespread associations with the bacterial 643 microbiome Supplementary Material 644 METHODS 645 ITS1F-2 and 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing 646 To identify fungal communities, we amplified DNA for the ITS1F-2 rRNA gene using single index reverse primers and a modified protocol of Smith & Peay (1) 647 and Nguyen et al. (2), as detailed in Griffiths et al. (3). We ran PCRs in duplicate using Solis BioDyne 5x HOT FIREPol® Blend Master Mix, 2μM primers and 648 1.5μl of sample DNA. Thermocycling conditions were 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30s, 52 °C for 20s and 72 °C for 30s, with a final 649 extension of 72 °C for 8 minutes. We quality checked the PCR products using a 2200 TapeStation (Agilent, USA). We combined PCR replicates into a single 650 PCR plate and cleaned products using HighPrepTM PCR clean up beads (MagBio, USA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. To normalise the 651 libraries, we combined 1ul of each sample and conducted a titration sequencing run with this pool using an Illumina v2 nano cartridge (paired end reads; 2 x 652 150bp) on the Illumina MiSeq at the University of Salford. Based on the percentage of reads sequenced per library, we calculated the volume required for the 653 full sequencing run and pooled these accordingly. ITS rRNA amplicon sequencing was conducted using paired-end reads (2 x 250bp) using an Illumina v2 654 cartridge on the MiSeq platform at the University of Salford. -

Fishery Conservation and Management Pt. 622, App. A

Fishery Conservation and Management Pt. 622, App. A vessel's unsorted catch of Gulf reef to complete prohibition), and seasonal fish: or area closures. (1) The requirement for a valid com- (g) South Atlantic golden crab. MSY, mercial vessel permit for Gulf reef fish ABC, TAC, quotas (including quotas in order to sell Gulf reef fish. equal to zero), trip limits, minimum (2) Minimum size limits for Gulf reef sizes, gear regulations and restrictions, fish. permit requirements, seasonal or area (3) Bag limits for Gulf reef fish. closures, time frame for recovery of (4) The prohibition on sale of Gulf golden crab if overfished, fishing year reef fish after a quota closure. (adjustment not to exceed 2 months), (b) Other provisions of this part not- observer requirements, and authority withstanding, a dealer in a Gulf state for the RD to close the fishery when a is exempt from the requirement for a quota is reached or is projected to be dealer permit for Gulf reef fish to re- reached. ceive Gulf reef fish harvested from the (h) South Atlantic shrimp. Certified Gulf EEZ by a vessel in the Gulf BRDs and BRD specifications. groundfish trawl fishery. [61 FR 34934, July 3, 1996, as amended at 61 FR 43960, Aug. 27, 1996; 62 FR 13988, Mar. 25, § 622.48 Adjustment of management 1997; 62 FR 18539, Apr. 16, 1997] measures. In accordance with the framework APPENDIX A TO PART 622ÐSPECIES procedures of the applicable FMPs, the TABLES RD may establish or modify the follow- TABLE 1 OF APPENDIX A TO PART 622Ð ing management measures: CARIBBEAN CORAL REEF RESOURCES (a) Caribbean coral reef resources.