Iraq: Fixing Security in Kirkuk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irakin Tilannekatsaus Marraskuussa 2017

RAPORTTI MIG-1725800 06.03.00 15.12.2017 MIGDno-2017-381 IRAKIN TILANNEKATSAUS MARRASKUUSSA 2017 Sisällys 1. Yleinen tilanne syksyllä 2017.....................................................................................................1 2. Turvallisuustilanne...................................................................................................................19 2.1. Väkivallan ilmenemismuodot ja voimakkuus .....................................................................19 2.2. Konfliktin luonne ja osapuolet............................................................................................20 2.2.1. Valtiolliset turvallisuusjoukot .......................................................................................20 2.2.2. Valtiota vastustavat ja muut aseelliset ryhmät ............................................................21 2.3. Siviilikuolemat ja loukkaantuneet.......................................................................................21 3. Turvallisuustilanne alueittain....................................................................................................22 4. Maan sisäisesti siirtymään joutuneet ja pakolaiset...................................................................44 5. Humanitaarinen tilanne............................................................................................................44 UNDP 28.6.2017. Rebuilding lives and neighbourhoods after conflict. Osoitteessa (30.11.2017): http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2017/6/28/Housing- by-people-rebuilding-lives-and-neighbourhoods-after-conflict.html...........................................64 -

Report on Iraq's Compliance with the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

Report on Iraq's Compliance with the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination SUBMITTED TO THE UN COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights (IHCHR) Baghdad 2018 1 Table of Contents Introduction: …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 The Convention in Domestic Law (Articles 1, 3 & 4): ……………………………………………………………..3 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 Process of democratization and Inter-Ethnic Relations (Articles 2 - 7): ……………………………..…. 3 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Effective Protection of Ethnic and Religious-Ethnic Groups against Acts of Racial Discrimination (Articles 2, 5 & 6): ………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Statistical Data Relating to the Ethnic Composition of the Population (Articles 1 & 5): ………….9 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..10 Legal Framework against Racial Discrimination (Articles 2-7): ……………………………………………. 10 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 11 National Human Rights Bodies to Combat Racial Discrimination (Articles 2-7): ………………….. 11 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..12 The Ethnic Composition of the Security and Police Services (Articles 5 & 2): ……………………… 12 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..13 Minority Representation in Politics (Articles 2 & 5): …………………………………………………………… 13 Recommendations: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

Wash Needs in Schools Iraq

COMPARATIVE OVERVIEW WASH NEEDS IN SCHOOLS OF KEY INDICATORS Note: Findings derived from WFP data are December 2019 IRAQ presented in turquoise boxes. Methodology Water Hygiene Sanitation 1 3 2 REACH Number of HH surveys conducted by Number of schools assessed by WFP Drinking water from a water source is available Drinking water from a water source is available Drinking water comes from an improved water source The water quality is perceived to be acceptable The main water source is at the school's premises Has access to handwashing facilities Has access to handwashing facilities of which is having water and soap available of which is functional of which is having soap Has access to improved sanitation facilities number of Average functional student toilets per school building number of toilets Average for students number of Average students per toilet Has access to student toilets separated by gender Has access to student toilets separated by gender Has unusable toilets Is having a good structural condition of student toilets Is having a good hygienic condition of student toilets Al-Falluja 115 88% 100% 78% 93% 100% 97% 100% 9,1 82% 0% Al-Ramadi 80 83% 98% 81% 98% 100% 100% 100% 8,6 93% 0% Al-Anbar Ana 74 31 44% 65% 87% 49% 72% 94% 94% 64% 66% 62% 94% 5,8 5,4 36 90% 90% 23% 100% 71% Heet 87 72% 100% 60% 100% 93% 97% 100% 9,0 88% 0% Shat Al-Arab 98 12% 92% 83% 11% 7,2 91 77% 56% 46% Al-Basrah Al-Khidhir 70 50% 66% 76% 11% 5,8 69 79% 74% 32% Al-Muthanna Al-Kufa 120 21% 46% 71% 99% 100% 23% 99% 6.5 71% 27% Al-Najaf Al-Najaf 94 2% 95% 98% -

Kirkuk and Its Arabization: Historical Background and Ongoing Issues In

Abstract The Arabization of the Kurdistan region in Iraq Since the establishment of the Iraqi state, the ruling Arab regimes forcibly displaced native Kurds and repopulated the area with Arab tribes. The change of demography,known as “Arabization,” existed in both Kurdish majority agriculture and urban lands. These policies were part of a larger Iraqi campaign to erase the Kurdish identity, occupy Kurdistan, and control its wealth. The Iraqi government’s campaign against the Kurds amounted to genocide and eventually destroyed Kurdish communities and the social fabric of Kurdistan. The areas affected by the Arabization stretch from eastern to northwestern Iraq , incorporating major cities,towns, and hundreds of villages. After the fall of Saddam Hussien’s dictatorship, these areas became referred to as “Disputed Territories'' in Iraq’s newly adopted constitution of 2005. Article 140 of Iraq’s constitution called for the normalization of the “Disputed Territories,” which was never implemented by the federal government of Iraq. 1 www.dckurd.org Kirkuk province, Khanagin city of Diyala province, Tuz Khurmatu District of Saladin Province, and Shingal (Sinjar) in Nineveh province are the main areas that continue to suffer from Arabization policies implemented in 1975. KIRKUK A key feature of Kirkuk is its diversity – Kurds, Arabs, Turkmens, Shiites, Sunnis, and Christians (Chaldeans and Assyrians) all co-exist in Kirkuk, and the province is even home to a small Armenian Christian population. GEOGRAPHY The province of Kirkuk has a population of more than 1.4 million, the overwhelming majority of whom live in Kirkuk city. Kirkuk city is 160 miles north of Baghdad and just 60 miles from Erbil, the capital of the Iraqi Kurdistan region. -

Weekly Explosive Incidents Flas

iMMAP - Humanitarian Access Response Weekly Explosive Hazard Incidents Flash News (25 June - 01 July2020) 79 673 11 6 4 INCIDENTS PEOPLE KILLED PEOPLE INJURED EXPLOSIONS AIRSTRIKES Federal Police Forces 01/JUL/2020 DIYALA GOVERNORATE Found and cleared 22 IEDs in Samarra district. Security Forces 25/JUN/2020 SALAH AL-DIN GOVERNORATE Destroyed an ISIS hideout and cleared a cache of explosives containing seven mortar Security Forces 25/JUN/2020 shells, three homemade IEDs, three detonators, and ammunition. Found and cleared a cache of explosives belonging to ISIS in the Al-Dhuluiya subdistrict. An Armed Group 26/JUN/2020 Coalition Forces 26/JUN/2020 Shot and killed a Security Forces member near Abu Al-Khanazer village on the outskirts of Launched several airstrikes and destroyed many ISIS hideouts and tunnels, killing 24 Abi Said subdistrict, northeast of Baqubah district. insurgents in Khanuka mountain. Popular Mobilization Forces 26/JUN/2020 Military Intelligence 29/JUN/2020 Destroyed five ISIS hideouts and killed five insurgents in the Al-Adhim area, north of Diyala. Found and cleared 24 IEDs and artillery shells in the Mukayshafa desert of Samarra district. ISIS 27/JUN/2020 Killed four Federal Police Forces members and injured two others in an attack at Abu Coalition Forces 29/JUN/2020 Al-Khanazer village, northeast of Baqubah district. Launched several airstrikes and destroyed many ISIS hideouts, killing everyone inside in Makhoul mountain of Baiji district. Popular Mobilization Forces 27/JUN/2020 Repelled an ISIS attack in Sheikh Jawamir village, north of Muqdadiya district. An Armed Group 30/JUN/2020 A targeted IED explosion struck a Popular Mobilization Forces patrol, killing four members Popular Mobilization Forces 27/JUN/2020 and injuring another, west of Baiji district. -

BACKGROUND GUIDE UNSC BBPS – Glengaze – MUN

BACKGROUND GUIDE UNSC BBPS – Glengaze – MUN Agenda – “Peace Building Measures in Post Conflict Regions with Special Emphasis on Iraq and Libya.” LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE BOARD Greetings, We welcome you to the United Nations Security Council, in the capacity of the members of the Executive Board of the said conference. Since this conference shall be a learning experience for all of you, it shall be for us as well. Our only objective shall be to make you all speak and participate in the discussion, and we pledge to give every effort for the same. How to research for the agenda and beyond? There are several things to consider. This background guide shall be different from the background guides you might have come across in other MUNs and will emphasise more on providing you the right Direction where you find matter for your research than to provide you matter itself, because we do not believe in spoon- feeding you, nor do we believe in leaving you to swim in the pond all by yourself. However, we promise that if you read the entire set of documents so provided, you shall be able to cover 70% of your research for the conference. The remaining amount of research depends on how much willing are you to put in your efforts and understand those articles and/or documents. So, in the purest of the language we can say, it is important to read anything and everything whose links are provided in the background guide. What to speak in the committee and in what manner? The basic emphasis of the committee shall not be on how much facts you read and present in the committee but how you explain them in simple and decent language to us and the fellow committee members. -

Iraq and the Kurds: the Brewing Battle Over Kirkuk

IRAQ AND THE KURDS: THE BREWING BATTLE OVER KIRKUK Middle East Report N°56 – 18 July 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. COMPETING CLAIMS AND POSITIONS................................................................ 2 A. THE KURDISH NARRATIVE....................................................................................................3 B. THE TURKOMAN NARRATIVE................................................................................................4 C. THE ARAB NARRATIVE .........................................................................................................5 D. THE CHRISTIAN NARRATIVE .................................................................................................6 III. IRAQ’S POLITICAL TRANSITION AND KIRKUK ............................................... 7 A. USES OF THE KURDS’ NEW POWER .......................................................................................7 B. THE PACE OF “NORMALISATION”........................................................................................11 IV. OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS................................................................ 16 A. THE KURDS.........................................................................................................................16 B. THE TURKOMANS ...............................................................................................................19 -

Iraq 2017 Human Rights Report

IRAQ 2017 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Iraq is a constitutional parliamentary republic. The outcome of the 2014 parliamentary elections generally met international standards of free and fair elections and led to the peaceful transition of power from former prime minister Nuri al-Maliki to Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi. Civilian authorities were not always able to exercise control of all security forces, particularly certain units of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) that were aligned with Iran. Violence continued throughout the year, largely fueled by the actions of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Government forces successfully fought to liberate territory taken earlier by ISIS, including Mosul, while ISIS sought to demonstrate its viability through targeted attacks. Armed clashes between ISIS and government forces caused civilian deaths and hardship. By year’s end Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) had liberated all territory from ISIS, drastically reducing ISIS’s ability to commit abuses and atrocities. The most significant human rights issues included allegations of unlawful killings by some members of the ISF, particularly some elements of the PMF; disappearance and extortion by PMF elements; torture; harsh and life-threatening conditions in detention and prison facilities; arbitrary arrest and detention; arbitrary interference with privacy; criminalization of libel and other limits on freedom of expression, including press freedoms; violence against journalists; widespread official corruption; greatly reduced penalties for so-called “honor killings”; coerced or forced abortions imposed by ISIS on its victims; legal restrictions on freedom of movement of women; and trafficking in persons. Militant groups killed LGBTI persons. There were also limitations on worker rights, including restrictions on formation of independent unions. -

Human Security Survey: Kirkuk, Iraq – 2019

Human Security Survey Kirkuk, Iraq — 2019 Gender Security Dynamics In April 2019, PAX and its local partner, the Iraqi Al-Amal Number of surveys completed per district Association, conducted the second round of the Human Security Survey (HSS) across all four districts of Kirkuk gov- ernorate to get a sense of the experiences of civilian popu- lations on issues regarding protection, conflict and security dynamics, and how they change over time. The first HSS was conducted in 2017 and did not include Hawija district as it was still under Da’esh control. Due to security and access challenges, the HSS was also not conducted in 2018 in the governorate. (See below for more information about the project, and please visit our website for additional re- ports in this series.) KIRKUK GOVERNORATE This report presents a summary of the findings in which The team conducted 613 interviews in Kirkuk the gendered dynamics of insecurity and conflict become specifically apparent, including the different ways in tween men and women shown in the report are generally which women and men in Kirkuk experience and perceive statistically significant at a 95% confidence level unless security. The results detailed here are drawn from inter- otherwise stated. However, it is likely that some gendered views with 320 women and 293 men. All differences be- differences may be understated given the sensitivities around such topics in the country. Conservative gender About the Human Security Survey: norms in the country can make it difficult to discuss issues The Human Security Survey (HSS) is a methodology devel- pertaining to ‘family honour’; we therefore anticipate oped by PAX’s Protection of Civilians (PoC) department to some level of underreporting of certain incidents, particu- collect data and facilitate constructive dialogue about civil- larly sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). -

Iraqi Kurdistan's Bid for Independence

Iraqi Kurdistan’s Bid for Independence: Challenges and Prospects Mustafa Gurbuz January 25, 2017 Masoud Barzani, the leader of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraqi Kurdistan, has expressed his expectation for “a big change” in US policy under President Donald Trump, adding that many of the officials assuming high positions in the Trump Administration are his personal friends or well acquainted with him and the Kurdistan region. In an interview on January 19 with The Washington Post at the World Economic Forum meeting at Davos, Barzani declared that “the time has come” for a fully independent Kurdistan recognized as a nation-state. “It is neither a rumor nor a dream. It is a reality that will come true. We will do everything in order to accomplish this objective, but peacefully and without violence,” said Barzani. “We will do our best to achieve that objective as early as possible,” he added. What are the implications of an independent Kurdistan? What will be the position of the Trump Administration on this issue? Given the unpredictable conditions in an increasingly sectarian Middle East and the unfinished war against the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the outcome of the Kurdish drive for independence will be determined by three major factors: (1) negotiations over the disputed territories in Iraq, (2) attitudes of regional powers, namely Turkey and Iran, and (3) intra-Kurdish competition for becoming a champion of Kurdish national identity. The Future of Disputed Territories In early January 2017, a multi-party delegation—including representatives from Kurdistan’s five parties in the government cabinet—was formed to start official talks with Baghdad about Kurdish independence. -

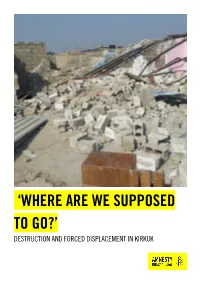

Destruction and Forced Displacement in Kirkuk

‘WHERE ARE WE SUPPOSED TO GO?’ DESTRUCTION AND FORCED DISPLACEMENT IN KIRKUK Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: House demolished in Wahed Huzeiran on 25 October by Kurdish forces. A family of 13 has (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. been made homeless as a result © Amnesty International https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 14/5094/2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 7 3. BACKGROUND 8 3.1 DISPLACEMENT IN KIRKUK 8 3.2 IS ATTACK 8 4. HOME DEMOLITIONS AND FORCED DISPLACEMENT 10 4.1 WAHED HUZAIRAN NEIGHBOURHOOD, KIRKUK CITY 10 4.2 OTHER NEIGHBOURHOODS OF KIRKUK CITY 12 4.3 DIBIS DISTRICT, KIRKUK GOVERNORATE 12 5.