The Fourteenth State Bill Doyle's 'Vermont Political Tradition'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1829 1830* 1831* 1832* 1833

1829 Samuel C. Crafts [National Republican] 14,325 55.8% Herman Allen [Anti-Masonic] 7,346 28.6% Joel Doolittle [Jacksonian] 3,973 15.5% Scattering 50 0.2% Total votes cast 25,694 44.2% 6 Though Allen of Burlington declined to identify himself with the party, he received the anti- masonic vote. 1830* Samuel C. Crafts [National Republican] 13,476 43.9% William A. Palmer [Anti-Masonic] 10,923 35.6% Ezra Meech [Jacksonian] 6,285 20.5% Scattering 37 0.1% Total votes cast 30,721 100.0% 1831* William A. Palmer [Anti-Masonic] 15,258 44.0% Heman Allen [National Republican] 12,990 37.5% Ezra Meech [Jacksonian] 6,158 17.8% Scattering 270 0.8% Total votes cast 34,676 100.0% 1832* William A. Palmer [Anti-Masonic] 17,318 42.2% Samuel C. Crafts [National Republican] 15,499 37.7% Ezra Meech [Jacksonian] 8,210 20.0% Scattering 47 0.1% Total votes cast 41,074 100.0% 1833 William A. Palmer [Anti-Masonic] 20,565 52.9% Ezra Meech [Democratic/National Republican] 15,683 40.3% Horatio Seymour [Whig] 1,765 4.5% John Roberts [Democratic] 772 2.0% Scattering 120 0.3% Total votes cast 38,905 100.0% 7 Coalition formed to challenge Anti-Masons. General Election Results: Governor, p. 7 of 29 1834* William A. Palmer [Anti-Masonic] 17,131 45.4% William C. Bradley [Democratic] 10,385 27.5% Horatio Seymour [Whig] 10,159 26.9% Scattering 84 0.2% Total votes cast 37,759 100.0% 1835* 8 William A. -

Centennial Proceedings and Other Historical Facts and Incidents Relating to Newfane

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world’s books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that’s often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book’s long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google’s system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

K:\Fm Andrew\21 to 30\27.Xml

TWENTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1841, TO MARCH 3, 1843 FIRST SESSION—May 31, 1841, to September 13, 1841 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1841, to August 31, 1842 THIRD SESSION—December 5, 1842, to March 3, 1843 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1841, to March 15, 1841 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—JOHN TYLER, 1 of Virginia PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—WILLIAM R. KING, 2 of Alabama; SAMUEL L. SOUTHARD, 3 of New Jersey; WILLIE P. MANGUM, 4 of North Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—ASBURY DICKENS, 5 of North Carolina SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—STEPHEN HAIGHT, of New York; EDWARD DYER, 6 of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—JOHN WHITE, 7 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—HUGH A. GARLAND, of Virginia; MATTHEW ST. CLAIR CLARKE, 8 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—RODERICK DORSEY, of Maryland; ELEAZOR M. TOWNSEND, 9 of Connecticut DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH FOLLANSBEE, of Massachusetts ALABAMA Jabez W. Huntington, Norwich John Macpherson Berrien, Savannah SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE REPRESENTATIVES 12 William R. King, Selma Joseph Trumbull, Hartford Julius C. Alford, Lagrange 10 13 Clement C. Clay, Huntsville William W. Boardman, New Haven Edward J. Black, Jacksonboro Arthur P. Bagby, 11 Tuscaloosa William C. Dawson, 14 Greensboro Thomas W. Williams, New London 15 REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas B. Osborne, Fairfield Walter T. Colquitt, Columbus Reuben Chapman, Somerville Eugenius A. Nisbet, 16 Macon Truman Smith, Litchfield 17 George S. Houston, Athens John H. Brockway, Ellington Mark A. Cooper, Columbus Dixon H. Lewis, Lowndesboro Thomas F. -

The Rise of Cornelius Peter Van Ness 1782- 18 26

PVHS Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society 1942 NEW SERIES' MARCH VOL. X No. I THE RISE OF CORNELIUS PETER VAN NESS 1782- 18 26 By T. D. SEYMOUR BASSETT Cornelius Peter Van Ness was a colorful and vigorous leader in a formative period of Vermont history, hut he has remained in the dusk of that history. In this paper Mr. Bassett has sought to recall __ mm and IUs activities and through him throw definite light on h4s --------- eventfultime.l.- -In--this--study Van--N-esr--ir-brought;-w--rlre-dt:a.mot~ months of his attempt in the senatorial election of I826 to succeed Horatio Seymour. 'Ulhen Mr. Bassett has completed his research into thot phase of the career of Van Ness, we hope to present the re sults in another paper. Further comment will he found in the Post script. Editor. NDIVIDUALISM is the boasted virtue of Vermonters. If they I are right in their boast, biographies of typical Vermonters should re veal what individualism has produced. Governor Van Ness was a typical Vermonter of the late nineteenth century, but out of harmony with the Vermont spirit of his day. This essay sketches his meteoric career in administrative, legislative and judicial office, and his control of Vermont federal and state patronage for a decade up to the turning point of his career, the senatorial campaign of 1826.1 His family had come to N ew York in the seventeenth century. 2 His father was by trade a wheelwright, strong-willed, with little book-learning. A Revolutionary colonel and a county judge, his purchase of Lindenwald, an estate at Kinderhook, twenty miles down the Hudson from Albany, marked his social and pecuniary success.s Cornelius was born at Lindenwald on January 26, 1782. -

Gouverneur (Vermont) > Kindle

02FB1D19DC ~ Gouverneur (Vermont) > Kindle Gouverneur (V ermont) By - Reference Series Books LLC Dez 2011, 2011. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 247x190x13 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Quelle: Wikipedia. Seiten: 52. Kapitel: Liste der Gouverneure von Vermont, Howard Dean, Robert Stafford, Israel Smith, Richard Skinner, William Slade, William P. Dillingham, William A. Palmer, Ebenezer J. Ormsbee, John Wolcott Stewart, Cornelius P. Van Ness, Martin Chittenden, Erastus Fairbanks, George Aiken, Samuel C. Crafts, Ernest Gibson junior, Moses Robinson, Stanley C. Wilson, J. Gregory Smith, Mortimer R. Proctor, Frederick Holbrook, James Hartness, John A. Mead, John L. Barstow, Paul Brigham, Deane C. Davis, Horace F. Graham, John Mattocks, Ryland Fletcher, Josiah Grout, Percival W. Clement, Charles Manley Smith, George Whitman Hendee, John G. McCullough, Paul Dillingham, Isaac Tichenor, Ezra Butler, Samuel E. Pingree, Urban A. Woodbury, Peter T. Washburn, Carlos Coolidge, Lee E. Emerson, Harold J. Arthur, Philip H. Hoff, Charles K. Williams, Horace Eaton, Charles W. Gates, Levi K. Fuller, John B. Page, Fletcher D. Proctor, William Henry Wills, Julius Converse, Charles Paine, John S. Robinson, Stephen Royce, Franklin S. Billings, Madeleine M. Kunin, Hiland Hall, George H. Prouty, Joseph B. Johnson, Edward Curtis Smith, Silas H. Jennison, Roswell Farnham, Redfield Proctor, William... READ ONLINE [ 4.18 MB ] Reviews Completely essential read pdf. It is definitely simplistic but shocks within the 50 % of your book. Its been designed in an exceptionally straightforward way which is simply following i finished reading through this publication in which actually changed me, change the way i believe. -- Damon Friesen Completely among the finest book I have actually read through. -

Speaker Ballot Votes STATE of VERMONT SPEAKERS of the HOUSE

STATE OF VERMONT SPEAKERS OF THE HOUSE Speaker Ballot Votes Joseph Bowker ...................................... 1778 Josiah Grout ................................. 1886-1890 Nathan Clark ......................................... 1778 Henry R. Start ........................................1890 Thomas Chandler, Jr..................... 1778-1780 Hosea A. Mann, Jr ....................... 1890-1892 Samuel Robinson ................................... 1780 William W. Stickney.................... 1892-1896 Thomas Porter .............................. 1780-1782 William A. Lord ........................... 1896-1898 Increase Moseley .......................... 1782-1783 Kittredge Haskins ........................ 1898-1900 Isaac Tichenor .............................. 1783-1784 Fletcher D. Proctor ...................... 1900-1902 Nathaniel Niles ............................. 1784-1785 John H. Merrifield ....................... 1902-1906 Stephen R. Bradley ....................... 1785-1786 Thomas C. Cheney ....................... 1906-1910 John Strong ............................................ 1786 Frank E. Howe ............................. 1910-1912 Gideon Olin .................................. 1786-1793 Charles A. Plumley ...................... 1912-1915 Daniel Buck .................................. 1793-1795 John E. Weeks ............................. 1915-1917 Lewis R. Morris ............................ 1795-1797 Stanley C. Wilson ..................................1917 Abel Spencer ................................ 1797-1798 Charles S. Dana -

General Election Results: Governor, P

1798 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 6,211 66.4% Moses Robinson [Democratic Republican] 2,805 30.0% Scattering 332 3.6% Total votes cast 9,348 33.6% 1799 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 7,454 64.2% Israel Smith [Democratic Republican] 3,915 33.7% Scattering 234 2.0% Total votes cast 11,603 100.0% 1800 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 6,444 63.4% Israel Smith [Democratic Republican] 3,339 32.9% Scattering 380 3.7% Total votes cast 10,163 100.0% 1802 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 7,823 59.8% Israel Smith [Democratic Republican] 5,085 38.8% Scattering 181 1.4% Total votes cast 13,089 100.0% 1803 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 7,940 58.0% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 5,408 39.5% Scattering 346 2.5% Total votes cast 13,694 100.0% 1804 2 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 8,075 55.7% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 6,184 42.7% Scattering 232 1.6% Total votes cast 14,491 100.0% 2 Totals do not include returns from 31 towns that were declared illegal. General Election Results: Governor, p. 2 of 29 1805 3 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 8,683 61.1% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 5,054 35.6% Scattering 479 3.4% Total votes cast 14,216 100.0% 3 Totals do not include returns from 22 towns that were declared illegal. 1806 4 Isaac Tichenor [Federalist] 8,851 55.0% Jonathan Robinson [Democratic Republican] 6,930 43.0% Scattering 320 2.0% Total votes cast 16,101 100.0% 4 Totals do not include returns from 21 towns that were declared illegal. -

Primary Sources Battle of Bennington Unit

Primary Sources Battle of Bennington Unit: Massachusetts Militia, Col. Simonds, Capt. Michael Holcomb James Holcomb Pension Application of James Holcomb R 5128 Holcomb was born 8 June 1764 and is thus 12 years old (!) when he first enlisted on 4 March 1777 in Sheffield, MA, for one year as a waiter in the Company commanded by his uncle Capt. Michael Holcomb. In April or May 1778, he enlisted as a fifer in Capt. Deming’s Massachusetts Militia Company. “That he attended his uncle in every alarm until some time in August when the Company were ordered to Bennington in Vermont […] arriving at the latter place on the 15th of the same month – that on the 16th his company joined the other Berkshire militia under the command of Col. Symonds – that on the 17th an engagement took place between a detachment of the British troops under the command of Col. Baum and Brechman, and the Americans under general Stark and Col. Warner, that he himself was not in the action, having with some others been left to take care of some baggage – that he thinks about seven Hundred prisoners were taken and that he believes the whole or a greater part of them were Germans having never found one of them able to converse in English. That he attended his uncle the Captain who was one of the guard appointed for that purpose in conducting the prisoners into the County of Berkshire, where they were billeted amongst the inhabitants”. From there he marches with his uncle to Stillwater. In May 1781, just before his 17th birthday, he enlisted for nine months in Capt. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Hclassifi Cation

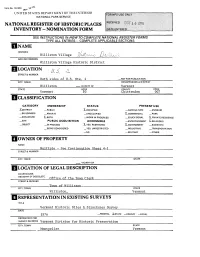

Form No. 10-300 ^ \Q~' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY ~ NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Williston Village AND/OR COMMON Williston Village Historic District LOCATION U.S. STREET & NUMBER Both sides of U.S. Rte. 2 _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Williston — VICINITY OF Vermont STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Vermont 50 Chit tend en 007 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE .X.DISTRICT _PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X_COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE X_BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL K.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED X-GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple - See Continuation Sheet 4-1 STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.-ETC. Office of the Town Clerk STREET & NUMBER Town of Williston CITY. TOWN STATE Williston, Vermont REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Vermont Historic Sites § Structures Survey DATE 1976 —FEDERAL XSTATE _COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Vermont Division for Historic Preservation CITY. TOWN STATE Montpelier Vermont DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE XEXCELLENT _DETERIORATED X_UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE XGOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED X.MOVED DATE_____ XFAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Williston Village Historic District includes residential, commercial, municipal buildings and churches which line both sides of U.S. Route 2. The architecturally and historically significant buildings number approximately twenty-two. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Galusha House

Form No. 10-300 REV. <9/77) DATA SHEET UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Galusha House AND/OR COMMON "Fairview" LOCATION STREET & NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION ',f CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Jericho xv*~k ' __ VICINITY OF Vermont STATE CODE COUNTY CODE -.Vermont .. ., ••, --,50 . r -.. ; , .., .., Ctiittenden... -,, ., . 007.,*-^; CLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE _MUSEUM _XBUILDING<S> X-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL 2LpRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —X.YES: RESTRICTED _GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —MILITARY- ,-. - - ,. —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME s/ Mr. and Mrs. Ray'F. Alien STREET & NUMBER 5971 S.W. 85 Street CITY, TOWN STATE Miami __ VICINITY OF Florida 33143 BLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS/ETC, Office.n.^^. ofr- the.-* Town™ Clerk/-i i STREETS NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Jericho Vermont OS465 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Vermont Historic Sites and Structures Survey DATE 1977 —FEDERAL X, STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Vermont Division .£or_.HisJ:Qzic_ Pres_eryatipn_. CITY, TOWN STATE Montpelier Vermont DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT -.DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE JK.GOOD _RUINS X-ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Galusha House is a handsome two-and-one-half story brick house laid in common bond, with a gable roof, set on a low stone foundation. -

This Is the Bennington Museum Library's “History-Biography” File, with Information of Regional Relevance Accumulated O

This is the Bennington Museum library’s “history-biography” file, with information of regional relevance accumulated over many years. Descriptions here attempt to summarize the contents of each file. The library also has two other large files of family research and of sixty years of genealogical correspondence, which are not yet available online. Abenaki Nation. Missisquoi fishing rights in Vermont; State of Vermont vs Harold St. Francis, et al.; “The Abenakis: Aborigines of Vermont, Part II” (top page only) by Stephen Laurent. Abercrombie Expedition. General James Abercrombie; French and Indian Wars; Fort Ticonderoga. “The Abercrombie Expedition” by Russell Bellico Adirondack Life, Vol. XIV, No. 4, July-August 1983. Academies. Reproduction of subscription form Bennington, Vermont (April 5, 1773) to build a school house by September 20, and committee to supervise the construction north of the Meeting House to consist of three men including Ebenezer Wood and Elijah Dewey; “An 18th century schoolhouse,” by Ruth Levin, Bennington Banner (May 27, 1981), cites and reproduces April 5, 1773 school house subscription form; “Bennington's early academies,” by Joseph Parks, Bennington Banner (May 10, 1975); “Just Pokin' Around,” by Agnes Rockwood, Bennington Banner (June 15, 1973), re: history of Bennington Graded School Building (1914), between Park and School Streets; “Yankee article features Ben Thompson, MAU designer,” Bennington Banner (December 13, 1976); “The fall term of Bennington Academy will commence (duration of term and tuition) . ,” Vermont Gazette, (September 16, 1834); “Miss Boll of Massachusetts, has opened a boarding school . ,” Bennington Newsletter (August 5, 1812; “Mrs. Holland has opened a boarding school in Bennington . .,” Green Mountain Farmer (January 11, 1811); “Mr.