In Search of the Meaning of Οικονομια

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TO the HISTORICAL RECEPTION of AUGUSTINE Volume 3

THE OXFORD GUIDE TO THE HISTORICAL RECEPTION OF AUGUSTINE Volume 3 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: KARLA POLLMANN EDITOR: WILLEMIEN OTTEN CO-EDITORS: JAM ES A. ANDREWS, A I. F. X ANDER ARWE ILER, IRENA BACKUS, S l LKE-PETRA BERGJAN, JOHANN ES BRACHTENDORF, SUSAN N EL KHOLI, MARK W. ELLIOTT, SUSANNE GAT ZEME I ER, PAUL VAN GEEST, BRUCE GORDON, DAVID LAMBERT, PETERLlEB REGTS, HILDEGUND MULLER, HI LMAR PABEL,JEAN-LOUlS QUANTlN, ER IC L. SAAK, LYDIA SC H UMACHER, ARNOUD VISSER, KONRAD VOSS l NG, J ACK ZUPKO. OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1478 I ORTHODOX CHURCH (SINCE 1453) --, Et~twickltmgsgesdLiclite des Erbsiit~dendogmas seit da Rejomw Augustiniana. Studien uber Augustin us Lmd .<eille Rezeption. Festgabefor tiall, Geschichtc des Erbsundendogmas. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte Willigis Eckermmm OSA Z llll l 6o. Geburtstag (Wiirzburg 1994) des Problems vom Ursprung des Obels 4 (Munich 1972 ). 25<,> - 90. P. Guilluy, 'Peche originel', Ca tl~al icis m e 10 (1985) 1036-61. R. Schwager, Erbsu11de und Heilsd,·ama im Kontcxt von Evolution, P. Henrici, '1l1e Philosophers and Original Sin', Conm1Unio 18 (•99•) Gcntechnology zmd Apokalyptik (Miinster 1997 ). 489-901. M. Stickelbroeck, U.-s tand, Fall 1md HrbsLinde. ln der nacilaugusti M. Huftier, 'Libre arbitrc, liberte et peche chez saint Augustin', nischen Ara bis zum Begimz der Sclwlastik. Die lateinische Theologie, Recherches de tlu!ologie a11 ciwne et medievale 33 (1966) 187-281. Handbuch der Dogmengeschichte 2/3a, pt 3 (Freiburg 2007 ) . M. F. johnson, 'Augustine and Aquinas on Original Sin; in B. D. Dau C. Straw, 'Gregory I; in A. D. Fitzgerald (ed.), Augusti11e through the phinais, B. -

Our Lady of the Ozarks Catholic Church

May 30, 2021 Bulletin – Most Holy Trinity Sunday Our Lady of the Ozarks Catholic Church 951 Swan Valley Drive Forsyth, MO 65653 phone: 417.546.5208 www.ourladyoftheozarks.com email: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday, Wednesday & Friday 8:00 am to 2:00 pm Weekend Mass Time: Sunday 8:30 am Father David Hulshof Weekday Mass Times: Wednesday & Friday 9:00 am Pastor Sacrament of Reconciliation: Sundays before Mass, Wednesdays after Mass 417-334-2928 Holy Hour Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament: Wednesdays after Mass [email protected] Father Samson Dorival Associate Pastor 417-334-2928 [email protected] Deacon Daniel Vaughn Pastoral Associate 417-546-5208 or 812-204-2625 [email protected] Marilyn Guy Financial Administrator Nancy Loughner Office Assistant Laura Cairns Music Ministry Welcome Blessings from our parish family Whether you are visiting for a short while, have moved here and are joining our parish, or are returning to your Catholic Faith, we want to welcome you to Our Lady of the Ozarks Church. Our parish is committed to inviting and supporting every parishioner to become a disciple of Christ, building His Kingdom through prayer, fellowship and service to others. We encourage you to connect with the people and ministries of our parish Our Lady of the Ozarks Mission Statement community and look forward to We are a unique parish called together from far and near. We bring meeting you personally. our talents and our shortcomings, our histories, and our hopes. Please call the parish office and Most of all, we bring our faith, and together in this faith we grow in let the friendship begin. -

SACRAMENTAL THEOLOGY and ECCLESIASTICAL AUTHORITY Dmusjankiewicz Fulton College Tailevu, Fiji

Andn1y.r Uniwr~itySeminary Stndics, Vol. 42, No. 2,361-382. Copyright 8 2004 Andrews University Press. SACRAMENTAL THEOLOGY AND ECCLESIASTICAL AUTHORITY DmusJANKIEWICZ Fulton College Tailevu, Fiji Sacramental theology developed as a corollary to Christian soteriology. While Christianity promises salvation to all who accept it, different theories have developed as to how salvation is obtained or transmitted. Understandmg the problem of the sacraments as the means of salvation, therefore, is a crucial soteriological issue of considerable relevance to contemporary Christians. Furthermore, sacramental theology exerts considerable influence upon ecclesiology, particularb ecclesiasticalauthority. The purpose of this paper is to present the historical development of sacramental theology, lea- to the contemporary understanding of the sacraments within various Christian confessions; and to discuss the relationship between the sacraments and ecclesiastical authority, with special reference to the Roman Catholic Church and the churches of the Reformation. The Development of Rom Catholic Sacramental Tbeohgy The Early Church The orign of modem Roman Catholic sacramental theology developed in the earliest history of the Christian church. While the NT does not utilize the term "~acrament,~'some scholars speculate that the postapostolic church felt it necessary to bring Christianity into line with other rebons of the he,which utilized various "mysterious rites." The Greek equivalent for the term "sacrament," mu~tmbn,reinforces this view. In addition to the Lord's Supper and baptism, which had always carried special importance, the early church recognized many rites as 'holy ordinances."' It was not until the Middle Ages that the number of sacraments was officially defked.2 The term "sacrament," a translation of the Latin sacramenturn ("oath," 'G. -

2. the Sacrament of Marriage and Its Impediments

THE SACRAMENT OF MARRIAGE AND ITS IMPEDIMENTS I. On Orthodox Marriage 1. The institution of the family is threatened today by such phenomena as secularization and moral relativism. The Orthodox Church maintains, as her fundamental and indisputable teaching, that marriage is sacred. The freely entered union of man and woman is an indispensable precondition for marriage. 2. In the Orthodox Church, marriage is considered to be the oldest institution of divine law because it was instituted simultaneously with the creation of Adam and Eve, the first human beings (Gen 2:23). Since its origin, this union not only implies the spiritual communion of a married couple—a man and a woman—but also assured the continuation of the human race. As such, the marriage of man and woman, which was blessed in Paradise, became a holy mystery, as mentioned in the New Testament where Christ performs His first sign, turning water into wine at the wedding in Cana of Galilee, and thus reveals His glory (Jn 2:11). The mystery of the indissoluble union between man and woman is an icon of the unity of Christ and the Church (Eph 5:32). 3. Thus, the Christocentric typology of the sacrament of marriage explains why a bishop or a presbyter blesses this sacred union with a special prayer. In his letter to Polycarp of Smyrna, Ignatius the God-Bearer stressed that those who enter into the communion of marriage must also have the bishop’s approval, so that their marriage may be according to God, and not after their own desire. -

Appendix I: an Extended Critique of Ecumenist Reasoning

This is a chapter from The Non-Orthodox: The Orthodox Teaching on Christians Outside of the Church. This book was originally published in 1999 by Regina Orthodox Press in Salisbury, MA (Frank Schaeffer’s publishing house). For the complete book, as well as reviews and related articles, go to http://orthodoxinfo.com/inquirers/status.aspx. (© Patrick Barnes, 1999, 2004) Appendix I: An Extended Critique of Ecumenist Reasoning Preliminary Remarks Before beginning our analysis, a few words need to be said about the term “ecumenist.” First, we Orthodox opposed to the more aberrant forms of ecumenism are not against ecumenism in its true and proper form—i.e., activities proper to the Apostolic mark of the Church (to be “sent out”), conducted in ways that do not violate Orthodox canonical guidelines. “Ecumenist” and “ecumenism” carry both positive and negative connotations which should be respectively qualified by words such as “true“ or “political“. In this book “ecumenist” is employed in its negative connotation, referring to a person “infected“ with what the Holy Fathers call the bacterium of an ecclesiological heresy. The chief symptoms of this disease are statements and activities that contradict or compromise the unity and uniqueness of the Church, and which expand Her boundaries in ways that are foreign to Her self-understanding. At an advanced stage, these symptoms often include an open espousal of various forms of the heretical Branch Theory of the Church, accompanied by an open disdain for those Faithful who stand opposed to the erosion of Holy Tradition and the Patristic mindset which so often characterizes Orthodox involvement in the ecumenical movement. -

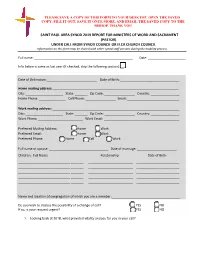

UNDER CALL from SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on This Form May Be Shared with Other Synod Staff Persons During the Mobility Process

PLEASE SAVE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO YOUR DESKTOP, OPEN THE SAVED COPY, FILL IT OUT, SAVE IT ONCE MORE, AND EMAIL THE SAVED COPY TO THE BISHOP. THANK YOU SAINT PAUL AREA SYNOD 2019 REPORT FOR MINISTERS OF WORD AND SACRAMENT (PASTOR) UNDER CALL FROM SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on this form may be shared with other synod staff persons during the mobility process Full name: _______________________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Info below is same as last year (if checked, skip the following section):__ Date of Ordination:____________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Home mailing address: ______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Home Phone: _______________ Cell Phone: _________________ Email: _____________________________ Work mailing address: _______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Work Phone: _________________________ Work Email: __________________________________________ Preferred Mailing Address: Home Work Preferred Email: Home Work Preferred Phone: Home Cell Work Full name of spouse: _________________________________ Date of marriage: ______________________ Children: Full Name Relationship Date of Birth _____________________________ _______ _________________________ ________________________ _____________________________ -

The Sacrament of Marriage and Its Impediments

The Canadian Journal of Orthodox Christianity Volume XI, Number 2, Spring 2016 The Sacrament of Marriage and Its Impediments The Synaxis of Primates of Local Orthodox Churches1 1. Orthodox Marriage 1) The institute of family is threatened today by such phenomena as secularization and moral relativism. The Orthodox Church asserts the sacral nature of marriage as her fundamental and indisputable doctrine. The free union of man and woman is an indispensable condition for marriage. 2) In the Orthodox Church, marriage is considered to be the oldest institution of divine law since it was instituted at the same time as the first human beings, Adam and Eve, were created (Gen. 2:23). Since its origin this union was not only the spiritual communion of the married couple – man and woman, but also assured the continuation of the human race. Blessed in Paradise, the marriage of man and woman became a holy mystery, which is mentioned in the New Testament in the story about Cana of Galilee, where Christ gave His first sign by turning water into wine thus revealing His glory (Jn. 2:11). The mystery of the indissoluble union of man and woman is the image of the unity of Christ and the Church (Eph. 5:32). 1 The document is approved by the Synaxis of the Primates of Local Orthodox Churches on January 21 – 28, 2016, in Chambesy, with the exception of representatives of the Orthodox Churches of Antioch and Georgia. 40 The Canadian Journal of Orthodox Christianity Volume XI, Number 2, Spring 2016 3) The Christ-centered nature of marriage explains why a bishop or a presbyter blesses this sacred union with a special prayer. -

Introduction to the Sacraments * There Are Three Elements in the Concept of a Sacrament: 1

Introduction to the Sacraments * There are three elements in the concept of a sacrament: 1. The external- a sensibly perceptible sign of sanctifying grace 2. Its institution by God 3. The actual conferring of grace * From the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1131)- Sacraments are efficacious signs of grace, instituted by Christ and entrusted to the Church, by which divine life is dispensed to us”. “Efficacious signs of grace” (CCC 1127, 1145-1152)- Efficacious means that something is successful in producing a desired or intended result; it’s effective. Sacraments are accompanied by special signs or symbols that produce what they signify. These are the external, sensibly perceptible signs. “..instituted by Christ” (CCC 1117) -no human power could attach an inward grace to an outward sign, only God could do that. During his public ministry, Jesus fashioned seven sacraments. The Church cannot institute new sacraments. There can never be more or less than 7. In the coming weeks as we look at each of the sacraments individually, you’ll learn about how Christ instituted each one. “… entrusted to the Church” (CCC 1118) – By Christ’s will, the Church oversees the celebration of the sacraments. “…divine life is dispensed to us” – This divine life is grace, it is a share in God’s own life. The sacraments give sanctifying grace which is the sharing in God’s own life that is the result of God’s love, the Holy Spirit, indwelling in the soul. Sanctifying grace is not the only grace God wants to give us. Each sacrament also gives the sacramental grace of that particular sacrament. -

The Catholic Doctrine of Transubstantiation Is Perhaps the Most Well Received Teaching When It Comes to the Application of Greek Philosophy

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2010 The aC tholic Doctrine of Transubstantiation: An Exposition and Defense Pat Selwood Bucknell University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Selwood, Pat, "The aC tholic Doctrine of Transubstantiation: An Exposition and Defense" (2010). Honors Theses. 11. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/11 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My deepest appreciation and gratitude goes out to those people who have given their support to the completion of this thesis and my undergraduate degree on the whole. To my close friends, Carolyn, Joseph and Andrew, for their great friendship and encouragement. To my advisor Professor Paul Macdonald, for his direction, and the unyielding passion and spirit that he brings to teaching. To the Heights, for the guidance and inspiration they have brought to my faith: Crescite . And lastly, to my parents, whose love, support, and sacrifice have given me every opportunity to follow my dreams. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………..………………………………………………1 Preface: Explanation of Terms………………...………………………………………......5 Chapter One: Historical Analysis of the Doctrine…………………………………...……9 -

V. an Evaluation of Heterodox Baptism

This is a chapter from The Non-Orthodox: The Orthodox Teaching on Christians Outside of the Church. This book was originally published in 1999 by Regina Orthodox Press in Salisbury, MA (Frank Schaeffer’s publishing house). For the complete book, as well as reviews and related articles, go to http://orthodoxinfo.com/inquirers/status.aspx. (© Patrick Barnes, 1999, 2004) V. An Evaluation of Heterodox Baptism Given that Holy Baptism is the “doorway into the Church,” the question of the validity of heterodox sacraments is crucial to our topic. Non-Orthodox Christians who wrestle with this issue often phrase it in this way: If I (speaking as a Protestant) have put on Christ through Baptism (Gal. 3:27), and am therefore a member of His Body (Eph. 5:30); and if His Body is the Church (Eph. 1:22- 23), then am I not also a member of the Church? And if the Orthodox Church is the ‘one True Church,’ how can I not be a member of it in some sense?56 A full treatment of how Orthodox should view the sacraments of heterodox Christians is beyond the scope of this work. What follows is merely a brief summary of what has been stated so eloquently and thoroughly by others.57 Although certain Orthodox would argue differently today, the traditional teaching is that the Church does not recognize the spiritual “validity” or efficacy of heterodox sacraments per se—i.e., in and of themselves, apart from the Church. Baptism is only given by and in the Church, “the eternal keeper of [ecclesial] grace” (Saint Seraphim of Sarov). -

The Synod Process

The Synod Process I Convocation and Preparation of the Synod 2 Preparatory Commission 1 The bishop convenes the synod with the consultation of the • Members of the preparatory commission are chosen by the bishop. Presbyteral Council. • The preparatory commission assists the bishop in organizing and preparing for the synod. • The bishop establishes a synodal secretariat and possibly a press office. 1 2 4 Preparatory phases of synod • Spiritual, catechetical and formational preparation 4 1. All are invited to pray for the ongoing intention of the synod and its results, that it might become an authentic 3 event of grace for the Church. 3 Publication of the Synodal 2. All should be informed on the nature and Directory purpose of the synod and the scope of its The Synodal Directory includes: deliberations. 1. composition of the synod; • Diocesan Consultation 2. norms by which elections of synodal members are to be conducted; 1. The faithful and the clergy of the Diocese 3. various offices to be exercised by the synod; are encouraged to express their needs, 4. procedural norms of the synod meetings. desires, challenges and opinions regarding the synod topics. 2. Meetings will take place at each parish, then deanery, to discuss synod topics. II Conducting the Synod • Determining the questions 1. The bishop determines the • The actual synod consists of the synodal sessions, questions on which the synodal typically in the cathedral. debate will concentrate. • Members of the synod make the profession of the faith before commencing synodal discussions. • Themes to be examined are introduced from a brief report; discussion begins. -

Catholics: a Sacramental People the Church in the 21St Century Center Serves As a Catalyst and a Resource for the Renewal of the Catholic Church in the United States

spring 2012 a catalyst and resource for the renewal of the catholic church catholics: a sacramental people The Church in the 21st Century Center serves as a catalyst and a resource for the renewal of the Catholic Church in the United States. about the editor from the c21 center director john f. baldovin, s.j., professor of historical and liturgical theology at the aboutBoston theCollege editor School of Theology and Dear Friends: richardMinistry, lennanreceived, ahis priest Ph.D. of in the religious The 2011–12 academic year marks the ninth year since the Church in the 21st Century Diocesestudies from of Maitland-Newcastle Yale University in 1982. in Fr. initiative was established by Fr. William P. Leahy, S.J., president of Boston College. And the Australia,Baldovin is is a professor member of thesystematic New York theologyProvince inof the SchoolSociety ofof TheologyJesus. He current issue of C21 Resources on Catholics: A Sacramental People is the 18th in the series of andhas servedMinistry as at advisor Boston to College, the National where Resources that spans this period. heConference also chairs of theCatholic Weston Bishops’ Jesuit The center was founded in the midst of the clerical sexual abuse crisis that was revealed in Department.Committee on He the studied Liturgy theology and was a atmember the Catholic of the InstituteAdvisory ofCommittee Sydney, Boston and the nation in 2002. C21 was intended to be the University’s response to this crisis theof the University International of Oxford, Commission and the on and set as its mission the goals of becoming a catalyst and resource for the renewal of the UniversityEnglish in theof Innsbruck, Liturgy.