Embracing Gayness with Integrity”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elevated Physical Health Risk Among Gay Men Who Conceal Their Homosexual Identity

Health Psychology Copyright 1996 by the American Psychological As..q~ation, Inc. 1996, Vol. 15, No. 4, 243-251 0278-6133/96/$3.110 Elevated Physical Health Risk Among Gay Men Who Conceal Their Homosexual Identity Steve W. Cole, Margaret E. Kemeny, Shelley E. Taylor, and Barbara R. Visscher University of California, Los Angeles This study examined the incidence of infectious and neoplastic diseases among 222 HIV- seronegative gay men who participated in the Natural History of AIDS Psychosocial Study. Those who concealed the expression of their homosexual identity experienced a significantly higher incidence of cancer (odds ratio = 3.18) and several infectious diseases (pneumonia, bronchitis, sinusitis, and tuberculosis; odds ratio = 2.91) over a 5-year follow-up period. These effects could not be attributed to differences in age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, repressive coping style, health-relevant behavioral patterns (e.g., drug use, exercise), anxiety, depression, or reporting biases (e.g., negative affectivity, social desirability). Results are interpreted in the context of previous data linking concealed homosexual identity to other physical health outcomes (e.g., HIV progression and psychosomatic symptomatology) and theories linking psychological inhibition to physical illness. Key words: psychological inhibition, cancer, infectious diseases, homosexuality Since at least the second century AD, clinicians have noted Such results raise the possibility that any health risks associ- that inhibited psychosocial characteristics seem to be associ- ated with psychological inhibition may extend beyond the ated with a heightened risk of physical illness (Kagan, 1994). realm of emotional behavior to include the inhibition of Empirical research in this area has focused on inhibited nonemotional thoughts and other kinds of mental or social expression of emotions as a risk factor for the development of behaviors, experiences, and impulses. -

Media Reference Guide

media reference guide NINTH EDITION | AUGUST 2014 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 1 GLAAD MEDIA CONTACTS National & Local News Media Sports Media [email protected] [email protected] Entertainment Media Religious Media [email protected] [email protected] Spanish-Language Media GLAAD Spokesperson Inquiries [email protected] [email protected] Transgender Media [email protected] glaad.org/mrg 2 / GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION FAIR, ACCURATE & INCLUSIVE 4 GLOSSARY OF TERMS / LANGUAGE LESBIAN / GAY / BISEXUAL 5 TERMS TO AVOID 9 TRANSGENDER 12 AP & NEW YORK TIMES STYLE 21 IN FOCUS COVERING THE BISEXUAL COMMUNITY 25 COVERING THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY 27 MARRIAGE 32 LGBT PARENTING 36 RELIGION & FAITH 40 HATE CRIMES 42 COVERING CRIMES WHEN THE ACCUSED IS LGBT 45 HIV, AIDS & THE LGBT COMMUNITY 47 “EX-GAYS” & “CONVERSION THERAPY” 46 LGBT PEOPLE IN SPORTS 51 DIRECTORY OF COMMUNITY RESOURCES 54 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 3 INTRODUCTION Fair, Accurate & Inclusive Fair, accurate and inclusive news media coverage has played an important role in expanding public awareness and understanding of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) lives. However, many reporters, editors and producers continue to face challenges covering these issues in a complex, often rhetorically charged, climate. Media coverage of LGBT people has become increasingly multi-dimensional, reflecting both the diversity of our community and the growing visibility of our families and our relationships. As a result, reporting that remains mired in simplistic, predictable “pro-gay”/”anti-gay” dualisms does a disservice to readers seeking information on the diversity of opinion and experience within our community. Misinformation and misconceptions about our lives can be corrected when journalists diligently research the facts and expose the myths (such as pernicious claims that gay people are more likely to sexually abuse children) that often are used against us. -

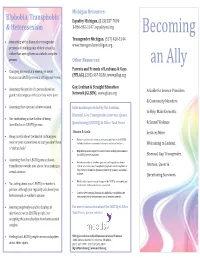

Becoming an Ally

Michigan Resources: Biphobia, Transphobia Equality Michigan, (313) 537-7000 & Heterosexism 1-866-962-1147, equalitymi.org Becoming Transgender Michigan, (517) 420-1544 • Interacting with a bisexual or transgender www.transgendermichigan.org person and thinking only of their sexuality, rather than seeing them as a whole, complex person. Other Resources: an Ally Parents and Friends of Lesbians & Gays • Changing your seat at a meeting or event because an LBGTIQ person is sitting next to you. (PFLAG), (202) 467-8180, www.pflag.org Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education • Assuming the gender of a person based on A Guide for Service Providers gender stereotypes or the sex they were born. Network (GLSEN), www.glsen.org & Community Members • Assuming that a person is heterosexual. Information provided by the Lesbian, to Help Make Domestic Bisexual, Gay, Transgender, Intersex, Queer, • Not confronting a joke for fear of being identified as an LBGTIQ person. Questioning (LBGTIQ) & Allies Task Force & Sexual Violence Mission & Goals: Services More • Being careful about the kind of clothing you • Enhance and increase access to advocacy and services for LBGTIQ wear or your mannerisms so that you don’t have individuals who are survivors of domestic and sexual violence. Welcoming to Lesbian, a “certain look.” • Help develop more supportive and inclusive working environments for LBGTIQ service providers. Bisexual, Gay, Transgender, • Assuming that if an LBGTIQ person shows • Provide education to member agencies and the public on issues friendliness towards you, she or he is making a related to heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia and transphobia as Intersex, Queer & sexual advance. they relate to the unique dynamics of LBGTIQ domestic and sexual violence. -

Other Indicia of Animus Against LGBT People by State and Local

Chapter 14: Other Indicia of Animus Against LGBT People by State and Local Officials, 1980-Present In this chapter, we draw from the 50 state reports to provide a sample of comments made by state legislators, governors, judges, and other state and local policy makers and officials which show animus toward LGBT people. Such statements likely both deter LGBT people from seeking state and local government employment and cause them to be closeted if they are employed by public agencies. In addition, these statements often serve as indicia of why laws extending legal protections to LGBT people are opposed or repealed. As the United States Supreme Court has recognized, irrational discrimination is often signaled by indicators of bias, and bias is unacceptable as a substitute for legitimate governmental interests.1 “[N]egative attitudes or fear, unsubstantiated by factors which are properly cognizable…are not permissible bases” for governmental decision-making.2 This concern has special applicability to widespread and persistent negative attitudes toward gay and transgender minorities. As Justice O‟Connor stated in her concurring opinion in Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558, 580-82 (2003): We have consistently held…that some objectives, such as “a bare...desire to harm a politically unpopular group,” are not legitimate state interests. … Moral disapproval of this group [homosexuals], like a bare desire to harm the group, is an interest that is insufficient to satisfy rational basis review under the Equal Protection Clause. 1 Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama v. Garrett, 531 U.S. 356, 367 (2001). 2 Id. (quoting Cleburne v Cleburne Living Center, 473 U.S. -

LGBTQI Terminology

LGBTQI Terminology A note about these definitions: Each of these definitions has been carefully researched and closely analyzed from theoretical and practical perspectives for cultural sensitivity, common usage, and general appropriateness. We have done our best to represent the most popular uses of the terms listed; however there may be some variation in definitions depending on location. Please note that each person who uses any or all of these terms does so in a unique way (especially terms that are used in the context of an identity label). If you do not understand the context in which a person is using one of these terms, it is always appropriate to ask. This is especially recommended when using terms that we have noted that can have a derogatory connotation. ******************************************************************************************** Ag / Aggressive - See ‘Stud.’ Agendered – Person is internally ungendered. Ally – Someone who confronts heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, heterosexual and genderstraight privilege in themselves and others; a concern for the well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and intersex people; and a belief that heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia and transphobia are social justice issues. Androgyne – Person appearing and/or identifying as neither man nor woman, presenting a gender either mixed or neutral. Asexual – Person who is not sexually attracted to anyone or does not have a sexual orientation. BDSM: (Bondage, Discipline/Domination, Submission/Sadism, and Masochism ) The terms ‘submission/sadism’ and ‘masochism’ refer to deriving pleasure from inflicting or receiving pain, often in a sexual context. The terms ‘bondage’ and ‘domination’ refer to playing with various power roles, in both sexual and social context. -

Scottish Fiction's Queer Communities

chapter 9 From Subtext to Gaytext? Scottish Fiction’s Queer Communities Carole Jones Abstract This chapter examines representations of queer groups in Scottish fiction to investi- gate whether the concept of community engaged with in these texts succeeds in pro- ducing a radical imagining of what Iris Marion Young calls an ‘openness to unassimilated otherness’ that resists the emerging homonormativity of gay identity. Keywords Queer – homosexuality – gay – community – Scottish fiction – drag queen – identity – homonormativity – Ali Smith – Luke Sutherland This chapter explores the presence of gay communities in Scottish fiction. Though a relatively recent phenomenon, these representations are ambivalent towards closed or strictly bounded social groupings and identities, and illus- trate uncertainties for queer people arising from the concept of community. In the early days of gay liberation, community delineated a liberatory alternative space to counter the often violent exclusions enacted by family, kinship, nation and other social formations. However, the interpellation to identity of such communities inevitably produces its own constraints and limitations, con- structing closures as well as opportunities for relations. This tension between the individual and community has vivid moments of expression in Scottish gay fictional representation as we move from the subterfuge of the queer-inflected characters in the early twentieth century, through the closeted mid-century, to a gradual but sometimes playfully carnivalesque coming out in -

LGBTQ Terminology

LGBTQ Terminology Below is a list of words and terms that are common within the LGBTQ community. This is not an all encompassing list, but is a good place start if you are unfamiliar. You may have heard some of these words and didn’t know what they meant. The purpose of this list is to help you understand the terms, and to educate on common terms and preferred terms within the LGBTQ community. AIDS / Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome – The stage of HIV infection. An HIV positive person is diagnosed with AIDS when their immune system is so weakened that it is no longer able to fight off illness. People with immune deficiency are much more vulnerable to infections such as pneumonia and various forms of cancer. These diseases are called opportunistic infections because they take advantage of the weakened immune system. Ultimately, people do not die from AIDS itself, they die from one or more of these opportunistic infections. It is believed that all people who become HIV+ will eventually have AIDS. Ally – Someone who confronts heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, heterosexual and gender-straight privilege in themselves and others; a concern for the well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and intersex people; a belief that heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia and transphobia are social. Androgynous - An appearance and/or identification that is neither man nor woman, presenting a gender either mixed or neutral. Asexual – Someone who does not experience sexual attraction. Unlike celibacy, which people choose, asexuality is an intrinsic part of who we are. Asexual people still have the same emotional needs as anyone else, and experience attraction. -

The Influence of Internalized Self-Prejudice on Anti-Gay Hate Crime Motivation

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2020 The Influence of Internalized Self-Prejudice on Anti-Gay Hate Crime Motivation Ross Michael Templeton Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Ross Templeton has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Carolyn Dennis, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Michael Brewer, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. James Frampton, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2020 Abstract The Influence of Internalized Self-Prejudice on Anti-Gay Hate Crime Motivation by Ross Templeton MA, Ashford University, 2011 BS, University of Minnesota, 2002 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Criminal Justice Walden University May 2020 Abstract The lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, and queer (LGBTQ) community continues to be negatively impacted by high rates of anti-gay hate crime. Gay-rights activists continue to press for public policy changes to improve equality and reduce anti-gay sentiment. -

173 Young Homosexual Adults

Young Homosexual Adults: What Keeps Some “Closeted” While Others are “Out?” Sonia Kuismanen Abstract This paper focuses on the present reasons for some people choosing to come out as a homosexual, while others choose to remain “in the closet” and live a heteronormative lifestyle. Traditionally societal pressures, which discouraged non-conformity, inhibited people from “coming out”, but with the advancement of genetic science the societal views seem to be changing and the people who may have once feared expression of their sexual orientation can now openly express themselves. Individuals that are choosing to come out often have family, friends, and lovers that they are connected with through attachment, love, lust, or any combination of the three. If people did not come out as lesbians, bisexuals, gays, or any other form of non-heterosexual they would not be faced with the additional conflicts and issues that the non-conforming population has to face. So what are the underlying causes for them to do so? Is it exposure to the LGBT community, purely nature, or a combination of the two? My focus is young adults of both genders that identify as lesbian or gay in our Western society. One of the main issues that out individuals face is social conflict. They never know who will be accepting and who will shun them. Introduction Children are conceived by a man and a woman; it is therefore safe to say that most of us were brought up thinking that little boys ought to like little girls, and little girls ought to like little boys. -

Identity Aggression and Student Speech Ari Ezra Waldman New York Law School

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2012 All Those Like You: Identity Aggression and Student Speech Ari Ezra Waldman New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the First Amendment Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation 77 Mo. L. Rev. 653 (2012) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. All Those Like You: Identity Aggression and Student Speech Ari Ezra Waldman- TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION II. IDENTITY-BASED AGGRESSION AS AN AT-TACK ON PERSONHOOD III. IDENTITY-BASED AGGRESSION AND TRADITIONAL PEER-TO-PEER AGGRESSION COMPARED A. DefinitionalSimilarities B. The Sociology ofldentity Based Aggression IV. IDENTITY-BASED AGGRESSION AND THE SUPREME COURT'S STUDENT SPEECH JURISPRUDENCE V. CONSISTENCY WITH LIBERAL AND CLASSICAL EDUCATIONAL VALUES A. Classic Aristotelian Values B. Modern Liberal Values VI. CONCLUSION I. INTRODUCTION According to recent studies, approximately eighty-nine percent of stu- dents have heard the word "gay" used frequently in school in a negative way and more than seventy-two percent reported hearing other homophobic re- marks (for example, "dyke" or "faggot") in school and online. Casual use of antigay rhetoric does not make it any less devastating. This verbal aggres- sion, including saying "that's so gay" 2 in a critical way and wearing t-shirts * Paul F. Lazarsfeld Fellow and Ph.D. candidate, Columbia University, De- partment of Sociology; Adjunct Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School; J.D., Har- vard Law School; A.B., magna cum laude, Harvard College. -

How the Church of Scientology Lures in Closeted Individuals

Relics, Remnants, and Religion: An Undergraduate Journal in Religious Studies Volume 3 Issue 1 Article 1 1-31-2018 How the Church of Scientology Lures in Closeted Individuals McKenna Cole [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/relics Recommended Citation Cole, McKenna (2018) "How the Church of Scientology Lures in Closeted Individuals," Relics, Remnants, and Religion: An Undergraduate Journal in Religious Studies: Vol. 3 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/relics/vol3/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Relics, Remnants, and Religion: An Undergraduate Journal in Religious Studies by an authorized editor of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cole: How the Church of Scientology Lures in Closeted Individuals Cole 1 McKenna Cole Professor White REL 215 May 9, 2017 How the Church of Scientology Lures in Closeted Individuals Using Kate Bornstein's memoir, Queer and Present Danger, as a primary source, HBO’s Alex Gibney’s documentary Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief and several other articles and interview; I will be analyzing the manner in which the Church of Scientology provided closeted homosexual and other ‘sexual deviants’ a false sense of hope. This is done through the promise of a structured community and the possibility of ridding individuals of their homosexual tendencies, which during this time was seen as a mental and physical illness. In 1950 L. Ron Hubbard, an American science fiction author, published his groundbreaking novel titled, Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health. -

Historicizing the Politics of Representation in Contemporary Queer Media David Hennessee California Polytechnic State University, [email protected]

Teaching Media Quarterly Volume 3 | Issue 2 Article 3 2015 Historicizing the Politics of Representation in Contemporary Queer Media David Hennessee California Polytechnic State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://pubs.lib.umn.edu/tmq Recommended Citation Hennessee, David. "Historicizing the Politics of Representation in Contemporary Queer Media." Teaching Media Quarterly 3, no. 2 (2015). http://pubs.lib.umn.edu/tmq/vol3/iss2/3 Teaching Media Quarterly is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Hennessee: Historicizing the Politics of Representation in Contemporary Quee Teaching Media Quarterly Volume 3, Edition 2 (Spring 2015): Queer Media Historicizing the Politics of Representation in Contemporary Queer Media Overview and Rationale I developed this assignment sequence for an upper-division LGBT literature and media course that I have taught since 2007. Students taking it typically have a great deal of enthusiasm for queer politics and media, and most have some knowledge of contemporary queer representations. However, their awareness doesn’t often extend before the late 1990s. Students may regard pop culture texts as mere entertainment and have little experience in media studies. Lacking perspective and a framework for analysis, students may tend to uncritically accept any contemporary representations of queer characters as exemplifying increasing visibility, awareness, and acceptance. These factors can limit students’ ability to critically analyze politics of representation in contemporary media. This assignment sequence addresses these concerns. It gives students a framework of analysis by constructing a genealogy of queer representation before and after Stonewall and extending to today. This framework helps students to understand the history of queer representation in film and television and to appreciate its real-world stakes, which can include positive or negative effects on the self-image of queer viewers.