Previous OBBA II Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Folk Music and the Radical Left Sarah C

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2015 If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left Sarah C. Kerley East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kerley, Sarah C., "If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2614. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2614 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left —————————————— A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History —————————————— by Sarah Caitlin Kerley December 2015 —————————————— Dr. Elwood Watson, Chair Dr. Daryl A. Carter Dr. Dinah Mayo-Bobee Keywords: Folk Music, Communism, Radical Left ABSTRACT If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left by Sarah Caitlin Kerley Folk music is one of the most popular forms of music today; artists such as Mumford and Sons and the Carolina Chocolate Drops are giving new life to an age-old music. -

To Read Broadside

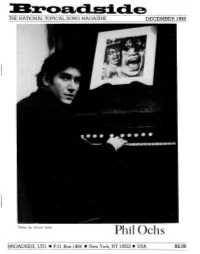

• -ad.sic:l.e THE NATIONAL TOPICAL SONG MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1983 Photo by Alice Ochs PhilOehs BROADSIDE, LTD .• P.O. Box 1464 • New York, NY 10023 • USA $2.00 2 lBx-<:>adside #147 BROADSIDE #147 The National Topical Song Magazine Published monthly by: Broadside, Ltd. P.O. Box 1464 New York, NY 10023 Publisher Norman A. Ross Editor Jeff Ritter Assistant Editors Gordon Grinberg Robin Ticho Contributing Editors Jane Friesen Paul Kaplan Sonny Ochs Ron Turner Illustrations by Agnes Friesen Kenneth E. Klammer Jane Ron Sonny Paul Poetry Editors D. B. Axelrod Friesen Turner Ochs Kaplan lC. Hand Editorial Board Sis Cunningham Gordon Friesen ISSN: 0740-7955 <D 1983, BROADSIDE LTD. Phil This issue of Broadside is a tribute to Phil Ochs, works, one of which is his song about Raygun's who would have been 43 years old on December invasion of Grenada! Finally, this issue contains six 19th. Phil was one of Broadside's most frequent songs "written" by Phil but never previously pub contributors over the years: the Index to Broadside lished either in print or on a record. These songs lists more than 70 of Phil's songs. Furthermore, the were among 15 or more that Phil sent on tape many pages of Broadside over these years were filled with years ago to his long-time friend Jim Glover and items by and about Phil and with songs written by which had been forgotten. Having recently redis Phil's contemporaries, many of whom were inspired covered them, Jim gave copies to Broadside (with by Phil--as we all were. -

Philip David Ochs, SMA ’58 (1940 – 1976)

Philip David Ochs, SMA ’58 (1940 – 1976) Phil was born in El Paso, TX, on December 19, 1940 and entered Staunton Military Academy (SMA) in the fall of 1956 graduating as a sergeant in the Corps Band in 1958. He loved music and may have started his singing career when he sang as a member of the U.S.S. North Sputniks in the 1958 SMA quartet contest with cadets James Lowe, James Ross, Robert Myers, and William Sneed. After graduating from SMA, Phil attended Ohio State University where he met Jim Glover who became his roommate. Jim’s father was Phil's political teacher. It was during this time, while he was majoring in journalism, that Phil formed his political beliefs. He started putting them to music in the three years before dropping out and going to New York where he started out singing at open mikes and passing the hat. Phil is best remembered for the protest songs on war and civil rights he wrote in the 1960's. He typically wrote about the topics of the day - civil rights, Viet Nam, hungry miners, and personalities such as Billy Sol Estes, William Worthy and Lou Marsh. By 1964 he was well enough established to release his first album, "All the News That's Fit To Sing". His second album, "I Ain't Marching Anymore," was released in 1965, and by 1966 he was able to sell out Carnegie Hall for his solo concert. In 1967 he signed with A&M Records where his first release was "Pleasures of the Harbor" in which he used heavily orchestrated arrangements for the first time. -

The New Frontier ◆ 81

The New 5 Frontier Early on a Saturday night in April 1961, a twenty-year-old singer carrying an over- sized guitar case walked into a dimly lit folk club, Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village, New York City. He was dressed casually: worn brown shoes, blue jeans, and a black wool jacket covering a plain yellow turtleneck sweater. A jumble of rumpled hair crowned his head, which was topped by a black corduroy Huck Finn cap. He pressed his lips together tightly and glanced at the tables of patrons, who sipped espresso and seemed to be arguing feverishly about current events. The singer looked serious and exhibited a nervousness that a friend had earlier tried to calm with four jiggers of Jim Beam bourbon. He slowly mounted the stage, opened his guitar case, and care- fully took out an old, nicked, six-string acoustic guitar, which he treated like an old friend. He fixed a wire harmonica holder around his neck and pushed a harmonica into place. As the singer stood alone on stage, motionless, a hush descended upon the coffeehouse. The audience, mostly white middle-class college students, many of them attending nearby New York University, politely applauded the singer. For a moment, the scene appeared to epitomize Eisenhower gentility and McCarthy repression: boys with closely cropped hair, button-down shirts, corduroy slacks, Hush Puppy shoes, and cardigans; and rosy-cheeked girls dressed in long skirts, bulky knit sweaters, and low-heeled shoes, who favoured long, straight, well-groomed hair. The singer shattered the genteel atmosphere when he began to strum a chord and sing. -

Phil Ochs: No Place in This World

College Quarterly - Summer 2005 Page 1 of 25 College Quarterly Summer 2005 - Volume 8 Number 3 Home Phil Ochs: No Place in this World Contents by Howard A. Doughty Abstract Phil Ochs was a prominent topical songwriter and singer in the 1960s. He was conventionally considered second only to Bob Dylan in terms of popularity, creativity and influence in the specific genre of contemporary folk music commonly known as "protest music". Whereas Dylan successfully reinvented himself many times in terms of his musical style and social commentaries, Ochs failed to win critical support when he, too, attempted to transform himself from a broadside balladeer into a more self-consciously artistic lyricist and performer. From the events at the Democratic Party convention in 1968 until his suicide in 1976, Phil Ochs' public and private life spiraled downward. Today, he would be readily identified as a victim of "bipolar disorder." Such a psychiatric assessment, while plausible in its own terms, says nothing about the political events that set the context for Phil Ochs' personal tragedy. This paper attempts to balance the individual and larger contextual themes. This article is prompted as much by personal reflection upon a particular man as it is by the ostensibly more general subject of his music, politics and relationship to American culture. Now, in the thirtieth year since his suicide, I am still seeking to sort out what, if anything, was the meaning of Phil Ochs' life, work and death to people who were outside his small circle of friends and family. I have made three attempts to put my own feelings in writing. -

In Th€Ir Own Words Bruce Polloc~

IN TH€IR OWN WORDS BRUCE POLLOC~ Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. New York Collier Macmillan Publishers London Riverside Community College Library 4800 Magnolia Avenue Riverside. CA 92506 Copyright © 1975 by Bruce Pollock All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photo- copying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. This book is dedicated to: 866 Third Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10022 Collier-Macmillan Canada Ltd. "Mom) The Gang) and My Baby" Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Pollock, Bruce. In their own words, 1. Rock musicians. 2. Music, Popular (Songs, etc.) -Writing and publishing. I.Title. ML3561.R62P64 784 74-23116 ISBN ()-Q2-597950-'7 "HOMETEAM CROWD" by Loudon Wain- wright III. © 1972 FRANK MUSIC CORP. Used by permission. The photograph of Doc Pomus is by Damon Runyon, Jr. The photograph of Gerry Goffin is by Barbara Goffin. First Printing 1975 Printed in the United States of America 46 / Newport Generation: 1961-1965 quickly taken into the mainstream of American life. This clean image of fireside folksinging, however, the camp-counselor-good- kid-college-youth (how come you never hear about the good teen-agers-because they never do anything), was nowhere near what real contemporary writing was all about. The goody-goody folksingers (and their prematurely mature followers) never saw beyond their ivory towers into the street. One of the few to escape the stigma was Peter, Paul, and Mary. -

Phil Ochs, Vietnam, and the National Press

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2016 All the News That’s Fit to Sing: Phil Ochs, Vietnam, and the National Press Thomas C. Waters Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Waters, Thomas Cody. "All the News That’s Fit to Sing: Phil Ochs, Vietnam, and the National Press" Master's thesis, Georgia Southern University, 2016. This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALL THE NEWS THAT’S FIT TO SING: PHIL OCHS, VIETNAM, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS by THOMAS CODY WATERS (Under the Direction of Eric Allen Hall) ABSTRACT Though a prolific topical musician and a prominent figure of the antiwar movement during the 1960s, Phil Ochs remains relatively understudied by scholars due to the lure of more commercially successful folk artists like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. His music facilitated awareness of pressing, and sometimes controversial, issues that would otherwise have not been discussed. Focusing on Ochs’ most musically productive years from 1964 until 1968, which coincide with the years of increased American involvement in Southeast Asia, this thesis analyzes Ochs in a way that has not been attempted before. -

Phil Ochs Pkupdated

Phil Ochs: There but for Fortune A film by Kenneth Bowser 98 minutes, Color and B/W, 2010 HDCAM, Stereo, 16:9 FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building, 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] “There’s no place in this world where I’ll belong, when I’m gone, And I won’t know the right from the wrong, when I’m gone, And you won’t find me singin’ on this song, when I’m gone. So I guess I’ll have to do it while I’m here” – Phil Ochs SYNOPSIS As our country continues to embroil itself in foreign wars and once again pins its hopes on a new leader’s promise for change, the feature length documentary, Phil Ochs: There But For Fortune is a timely tribute to an unlikely American hero. Phil Ochs, a folk singing legend, who many called “the emotional heart of his generation,” loved his country and he pursued its honor, in song and action, with a ferocity that had no regard for consequences. Wielding only a battered guitar, a clear voice and a quiver of razor sharp songs, he tirelessly fought the “good fight” for peace and justice throughout his short life. Phil Ochs rose to fame in the early 1960’s during the height of the folk and protest song movement. His songs, with lyrics ripped straight from the daily news, spoke to those emboldened by the hopeful idealism of the day. -

WHATS-NEW-With-The-Yachtsmen

WHAT’S NEW with THE YACHTSMEN by Malcolm C. Searles Contents Introduction!!!!!!!!!Page ii CHAPTER ONE : !!The Yachtsmen !!!Page 4 CHAPTER TWO : !!Mickey Elley!!!!Page 17 CHAPTER THREE : !The What’s New!!!Page 28 CHAPTER FOUR :!!Colin Scot!! ! ! ! Page 40 First PDF Edition by Malcolm C. Searles © Dojotone Publications 2018 Layout and Editing by Malcolm C. Searles Photographic Credits: All photographs are from various sources. If any particular credit should be acknowledged, and has unknowingly been missed out, then I would be happy to correct any missing information for future editions. Please contact the author. The right of Malcolm C. Searles to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988. All rights reserved. No written part of this publication may be transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. This edition is made available subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the author’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is herewith available. dojotonepublications.com i INTRODUCTION “In te land of Odin, tere stands a mountain...” A sk me a year or so ago, I would have had no concept as to whom The Yachtsmen, or their latter-day counterparts The What’s New were – or how they fit into the realms of the mighty musical magnitude. Living in a sleepy landlocked U.K. -

Nicholas Booker, University of Northern Colorado

So Many Reasons for Revival: Politics and Commercialism in the Second Wave of the Folk Revival in the United States, 1958–1965 Nicholas Booker University of Northern Colorado Abstract Numerous scholars have taken positions which place the political music of the second wave of the folk revival in the United States from 1958 to 1965 at odds with commercialism of the time. Commercial and political motivations have been seen as mutually exclusive factors that detracted from the efficacy and cultural applicability of one another. This research will show that such a viewpoint is inconsistent with evidence in certain instances, especially with regard to increasing college audiences, organizations such as the Newport Folk Festival, and the highly intentional partnership between political musicians such as Pete Seeger and Phil Ochs on the one hand and commercially successful musicians such as Theodore Bikel, Judy Collins, and Peter, Paul, and Mary on the other. Through a meta-analysis of scholarship on the subject, an examination of sources within the movement and outside of it, and an analysis of the music and lyrics created by musicians within the movement, this paper will show that far from being mutually exclusive, political action and commercialism in the second wave of the folk revival supported and sustained one another in numerous instances. Keywords: Folk, Revival, Politics Introduction Between the years 1958 and 1965 folk music underwent dramatic changes in the United States especially with regard to the political and commercial nature of the music. Folk music assumed a more prominent role in popular culture, especially with younger generations of listeners and participants.1 Based primarily out of Greenwich Village in New York City, this 1 Robert Cantwell, When We Were Good (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996), 2; Stephanie Ledgin, Discovering Folk Music (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2010), 39–40; Kip Lornell, Exploring American Folk Music (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2012), 259.