Music, Nostalgia and Estrangement in Twin Peaks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Readings Monthly

FREE FEBRUARY 2012 Readings Monthly Gregory Day on Carrie Tiffany • Mark Rubbo on Peter Carey EE P18 S . OLD IDEAS CD IMAGE ADAPTED FROM COVER OF LEONARD COHEN'S NEW Leonard Cohen is back with some Old Ideas February book, CD & DVD new-releases. More new-releases inside. AUS. FICTION AUS. FICTION YOUNG ADULT AUS CRIME PHILOSOPHY DVD POP CD CLASSICAL $39.95 $29.95 $19.95. e $16.99 $16.95 $29.95 $35.00 $29.95 $39.95 $26.95 $21.95 $36.95 >> p5 >> p4 >> p9 >> p10 >> p13 >> p17 >> p18 >> p19 February event highlights : George Megalogenis with Barrie Cassidy, Kirsten Tranter, Elliot Perlman and Arnold Zable. More events inside. All shops open 7 days, except State Library shop, which is open Mon- Sat. Carlton 309 Lygon St 9347 6633 Hawthorn 701 Glenferrie Rd 9819 1917 Malvern 185 Glenferrie Rd 9509 1952 Port Melbourne 253 Bay St 9681 9255 St Kilda 112 Acland St 9525 3852 Readings at the State Library of Victoria 328 Swanston St 8664 7540 email us at [email protected] Browse and buy online at www.readings.com.au and at ebooks.readings.com.au Programme one Bookings n ow oPen With 200+ events per year, there is something for everyone. The majority of events are free and book out quickly. Don’t miss out go to wheelercentre.com 2 Readings Monthly February 2012 to Australian literature as well as a single work. Open to Victorian residents, all writing genres are eligible. The $5000 From the Editor Civic Choice Award 2012 will be offered during the finalist exhibition at Federa- A LONG GOODBYE ThisREADINGS EXC LUSIVEMonth’s most importantly News from Readings custom- tion Square in November 2012. -

Collection of Scripts for Survivors and Paris 7000, 1969-1970

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8z60tr2 No online items Collection of scripts for Survivors and Paris 7000, 1969-1970 Finding aid prepared by UCLA Arts Special Collections staff, 2004; initial EAD encoding by Julie Graham; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 19 November 2016. Collection of scripts for Survivors PASC 258 1 and Paris 7000, 1969-1970 Title: Collection of Scripts for Survivors and Paris 7000 Collection number: PASC 258 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 1.0 linear ft.(2 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1969-1970 Abstract: John Wilder was the producer of the television series The Survivors (1969) and Paris 7000 (1970). The collection consists of scripts and production information related to the two programs. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

Au Revoir Simone Remix Album Mp3, Flac, Wma

Au Revoir Simone Remix Album mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Remix Album Country: US Style: Synth-pop, Downtempo MP3 version RAR size: 1573 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1359 mb WMA version RAR size: 1561 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 193 Other Formats: AC3 FLAC MPC VQF AIFF MP4 MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits Another Likely Story (Neon Indian Remix) 1 Remix – Neon Indian Another Likely Story (Aeroplane Remix) 2 Remix – Aeroplane Shadows (The Teenagers Remix) 3 Remix – The Teenagers Shadows (Tanlines Remix) 4 Remix – Tanlines The Lucky One (Slow Club Remix) 5 Remix – Slow Club Sad Song (Pacific! Remix) 6 Remix – Pacific! Fallen Snow (The Teenagers Remix) 7 Remix – The Teenagers If I Could Sleep (Darkel Remix) 8 Remix – Darkel A Violent Yet Flammable World (Montag Remix) 9 Remix – Montag Don't See The Sorrow (Keith Murray Remix) 10 Remix – Keith Murray Dark Halls (Best Fwends Remix) 11 Remix – Best Fwends Night Majestic (Matt Harding Remix) 12 Remix – Matt Harding Stars (Disco Pusher Remix) 13 Remix – Disco Pusher Lark (Ruff & Jam Remix) 14 Remix – Ruff & Jam 15 The Way To There (ReRunner Remix) Sad Song (Alexis Taylor Remix) 16 Remix – Alexis Taylor Sad Song (Air France) 17 Remix – Air France The Way To There (Mark-Anthony Tieku Remix) 18 Remix – Mark-Anthony Tieku Companies, etc. Published By – Lipsync Music – none Notes Custom printed artwork, housed in a standard jewel box. CDr has hand-written label in black marker with company contact details. Related Music albums to Remix Album by Au Revoir Simone 1. DJ Ruffstuff - The Mystical (Turno Remix) / What's Up (Nu Elementz Remix) 2. -

Bertus in Stock 7-4-2014

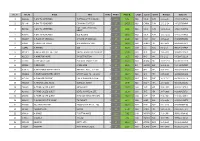

No. # Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price €. Origin Label Genre Release Eancode 1 G98139 A DAY TO REMEMBER 7-ATTACK OF THE KILLER.. 1 12in 6,72 NLD VIC.R PUN 21-6-2010 0746105057012 2 P10046 A DAY TO REMEMBER COMMON COURTESY 2 LP 24,23 NLD CAROL PUN 13-2-2014 0602537638949 FOR THOSE WHO HAVE 3 E87059 A DAY TO REMEMBER 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 14-11-2008 0746105033719 HEART 4 K78846 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 31-10-2011 0746105049413 5 M42387 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS 1 LP 20,23 NLD MOV POP 13-6-2013 8718469532964 6 L49081 A FOREST OF STARS A SHADOWPLAY FOR.. 2 LP 38,68 NLD PROPH HM. 20-7-2012 0884388405011 7 J16442 A FRAMES 333 3 LP 38,73 USA S-S ROC 3-8-2010 9991702074424 8 M41807 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVE YOU'RE ALWAYS ON MY MIND 1 LP 24,06 NLD PHD POP 10-6-2013 0616892111641 9 K81313 A HOPE FOR HOME IN ABSTRACTION 1 LP 18,53 NLD PHD HM. 5-1-2012 0803847111119 10 L77989 A LIFE ONCE LOST ECSTATIC TRANCE -LTD- 1 LP 32,47 NLD SEASO HC. 15-11-2012 0822603124316 11 P33696 A NEW LINE A NEW LINE 2 LP 29,92 EU HOMEA ELE 28-2-2014 5060195515593 12 K09100 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH AND HELL WILL.. -LP+CD- 3 LP 30,43 NLD SPV HM. 16-6-2011 0693723093819 13 M32962 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH LAY MY SOUL TO. -

The Art of David Lynch

The Art of David Lynch weil das Kino heute wieder anders funktioniert; für ei- nen wie ihn ist da kein Platz. Aber deswegen hat Lynch ja nicht seine Kunst aufgegeben, und nicht einmal das Filmen. Es ist nur so, dass das Mainstream-Kino den Kaperversuch durch die Kunst ziemlich fundamental abgeschlagen hat. Jetzt den Filmen von David Lynch noch einmal wieder zu begegnen, ist ein Glücksfall. Danach muss man sich zum Fernsehapparat oder ins Museum bemühen. (Und grimmig die Propaganda des Künstlers für den Unfug transzendentaler Meditation herunterschlucken; »nobody is perfect.«) Was also ist das Besondere an David Lynch? Seine Arbeit geschah und geschieht nach den »Spielregeln der Kunst«, die bekanntlich in ihrer eigenen Schöpfung und zugleich in ihrem eigenen Bruch bestehen. Man er- kennt einen David-Lynch-Film auf Anhieb, aber niemals David Lynch hat David Lynch einen »David-Lynch-Film« gedreht. Be- 21 stimmte Motive (sagen wir: Stehlampen, Hotelflure, die Farbe Rot, Hauchgesänge von Frauen, das industrielle Rauschen, visuelle Americana), bestimmte Figuren (die Frau im Mehrfachleben, der Kobold, Kyle MacLachlan als Stellvertreter in einer magischen Biographie - weni- ger, was ein Leben als vielmehr, was das Suchen und Was ist das Besondere an David Lynch? Abgesehen Erkennen anbelangt, Väter und Polizisten), bestimmte davon, dass er ein paar veritable Kultfilme geschaffen Plot-Fragmente (die nie auflösbare Intrige, die Suche hat, Filme, wie ERASERHEAD, BLUE VELVET oder die als Sturz in den Abgrund, die Verbindung von Gewalt TV-Serie TWIN PEAKS, die aus merkwürdigen Gründen und Design) kehren in wechselnden Kompositionen (denn im klassischen Sinn zu »verstehen« hat sie ja nie wieder, ganz zu schweigen von Techniken wie dem jemand gewagt) die genau richtigen Bilder zur genau nicht-linearen Erzählen, dem Eindringen in die ver- richtigen Zeit zu den genau richtigen Menschen brach- borgenen Innenwelten von Milieus und Menschen, der ten, und abgesehen davon, dass er in einer bestimmten Grenzüberschreitung von Traum und Realität. -

Serial Historiography: Literature, Narrative History, and the Anxiety of Truth

SERIAL HISTORIOGRAPHY: LITERATURE, NARRATIVE HISTORY, AND THE ANXIETY OF TRUTH James Benjamin Bolling A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Minrose Gwin Jennifer Ho Megan Matchinske John McGowan Timothy Marr ©2016 James Benjamin Bolling ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Ben Bolling: Serial Historiography: Literature, Narrative History, and the Anxiety of Truth (Under the direction of Megan Matchinske) Dismissing history’s truths, Hayden White provocatively asserts that there is an “inexpugnable relativity” in every representation of the past. In the current dialogue between literary scholars and historical empiricists, postmodern theorists assert that narrative is enclosed, moribund, and impermeable to the fluid demands of history. My critical intervention frames history as a recursive, performative process through historical and critical analysis of the narrative function of seriality. Seriality, through the material distribution of texts in discrete components, gives rise to a constellation of entimed narrative strategies that provide a template for human experience. I argue that serial form is both fundamental to the project of history and intrinsically subjective. Rather than foreclosing the historiographic relevance of storytelling, my reading of serials from comic books to the fiction of William Faulkner foregrounds the possibilities of narrative to remain open, contingent, and responsive to the potential fortuities of historiography. In the post-9/11 literary and historical landscape, conceiving historiography as a serialized, performative enterprise controverts prevailing models of hermeneutic suspicion that dominate both literary and historiographic skepticism of narrative truth claims and revives an ethics responsive to the raucous demands of the past. -

David Cronenberg Et Howard Shore. Bref Portrait D'une Longue

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 00:20 Revue musicale OICRM David Cronenberg et Howard Shore. Bref portrait d’une longue collaboration Solenn Hellégouarch Une relève Résumé de l'article Volume 2, numéro 2, 2015 Après 45 ans de carrière, la filmographie de David Cronenberg compte 22 films, dont 15 ont été musicalisés par Howard Shore, qui a rejoint l’équipe du URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1060132ar cinéaste en 1979. Si l’univers cronenbergien est aujourd’hui bien connu, DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1060132ar l’apport de son compositeur demeure peu exploré. Or, la musique semble y jouer un rôle de toute première importance, le compositeur étant impliqué très Aller au sommaire du numéro tôt dans le processus cinématographique. Cette implication précoce est indicatrice du rôle central qu’occupent Shore et sa musique : comment le définir ? Plutôt que de recourir à une analyse des fonctions de la musique au cinéma, cet article explore les processus de création qui lui donnent naissance. Éditeur(s) Cronenberg et Shore, qui ont « tout appris en commun », présentent ainsi des OICRM processus créateurs aux traits similaires, ou plus exactement des figures artistiques communes, ici exposées, les regroupant sous une seule vision artistique : l’autodidacte, l’expérimentateur, l’improvisateur, le ISSN peintre/sculpteur et l’artiste-artisan. 2368-7061 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Hellégouarch, S. (2015). David Cronenberg et Howard Shore. Bref portrait d’une longue collaboration. Revue musicale OICRM, 2(2), 96–114. https://doi.org/10.7202/1060132ar Tous droits réservés © Revue musicale OICRM, 2015 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. January 5, 2015 to Sun. January 11, 2015 Monday January 5, 2015 Tuesday January 6, 2015

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. January 5, 2015 to Sun. January 11, 2015 Monday January 5, 2015 5:30 PM ET / 2:30 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Gene Simmons Family Jewels Baltic Coasts Face Your Demons - While on tour in Amsterdam, Gene and Shannon spend some quality time The Bird Route - Every spring and autumn, thousands of migrating birds over the Western with a young fan writing a school report. Pomeranian bodden landscape deliver one of the most breathtaking nature spectacles. 6:30 PM ET / 3:30 PM PT 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT Gene Simmons Family Jewels Smart Travels Europe What Happens In Vegas... - Gene and Shannon get invited to the premiere of the new Cirque du Out of Rome - We leave the eternal city behind by way of the famous Apian Way to explore the Soleil show “Viva Elvis” in Las Vegas. environs of Rome. First it’s the majesty of Emperor Hadrian’s villa and lakes of the Alban Hills. Next, it’s south to the ancient seaport of Ostia, Rome’s Pompeii. Along the way we sample olive 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT oil, stop at the ancient’s favorite beach and visit a medieval hilltop town. Our own five star villa Gene Simmons Family Jewels is a retreat fit for an emperor. God Of Thund - An exhausted Shannon reaches her limit with Gene’s snoring and sends him packing to a sleep doctor. 9:30 AM ET / 6:30 AM PT The Big Interview Premiere Alan Alda - Hollywood’s Mr. -

Twin Peaks’ New Mode of Storytelling

ARTICLES PROPHETIC VISIONS, QUALITY SERIALS: TWIN PEAKS’ NEW MODE OF STORYTELLING MIKHAIL L. SKOPTSOV ABSTRACT Following the April 1990 debut of Twin Peaks on ABC, the TV’, while disguising instances of authorial manipulation evi- vision - a sequence of images that relates information of the dent within the texts as products of divine internal causality. narrative future or past – has become a staple of numerous As a result, all narrative events, no matter how coincidental or network, basic cable and premium cable serials, including inconsequential, become part of a grand design. Close exam- Buffy the Vampire Slayer(WB) , Battlestar Galactica (SyFy) and ination of Twin Peaks and Carnivàle will demonstrate how the Game of Thrones (HBO). This paper argues that Peaks in effect mode operates, why it is popular among modern storytellers had introduced a mode of storytelling called “visio-narrative,” and how it can elevate a show’s cultural status. which draws on ancient epic poetry by focusing on main char- acters that receive knowledge from enigmatic, god-like figures that control his world. Their visions disrupt linear storytelling, KEYWORDS allowing a series to embrace the formal aspects of the me- dium and create the impression that its disparate episodes Quality television; Carnivale; Twin Peaks; vision; coincidence, constitute a singular whole. This helps them qualify as ‘quality destiny. 39 SERIES VOLUME I, SPRING 2015: 39-50 DOI 10.6092/issn.2421-454X/5113 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TV SERIAL NARRATIVES ISSN 2421-454X ARTICLES > MIKHAIL L. SKOPTSOV PROPHETIC VISIONS, QUALITY SERIALS: TWIN PEAKS’ NEW MODE OF STORYTELLING By the standards of traditional detective fiction, which ne- herself and possibly The Log Lady, are visionaries as well. -

The Portrayal of Tourette Syndrome in Film and Television Samantha Calder-Sprackman, Stephanie Sutherland, Asif Doja

ORIGINAL ARTICLE COPYRIGHT ©2014 T HE CANADIAN JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGICAL SCIENCES INC . The Portrayal of Tourette Syndrome in Film and Television Samantha Calder-Sprackman, Stephanie Sutherland, Asif Doja ABSTRACT: Objective: To determine the representation of Tourette Syndrome (TS) in fictional movies and television programs by investigating recurrent themes and depictions. Background: Television and film can be a source of information and misinformation about medical disorders. Tourette Syndrome has received attention in the popular media, but no studies have been done on the accuracy of the depiction of the disorder. Methods: International internet movie databases were searched using the terms “Tourette’s”, “Tourette’s Syndrome”, and “tics” to generate all movies, shorts, and television programs featuring a character or scene with TS or a person imitating TS. Using a grounded theory approach, we identified the types of characters, tics, and co-morbidities depicted as well as the overall representation of TS. Results: Thirty-seven television programs and films were reviewed dating from 1976 to 2010. Fictional movies and television shows gave overall misrepresentations of TS. Coprolalia was overrepresented as a tic manifestation, characters were depicted having autism spectrum disorder symptoms rather than TS, and physicians were portrayed as unsympathetic and only focusing on medical therapies. School and family relationships were frequently depicted as being negatively impacted by TS, leading to poor quality of life. Conclusions: Film and television are easily accessible resources for patients and the public that may influence their beliefs about TS. Physicians should be aware that TS is often inaccurately represented in television programs and film and acknowledge misrepresentations in order to counsel patients accordingly. -

Valwood Summer Study

“Reading is always an act of empathy. It's always an imagining of what it's like to be someone else.” --John Green Valwood Summer Study English I Note: Obtain your own copy of the book and bring it to class when school begins. Assignment: Read Chains by Laurie Halse Anderson. As you read, do all of the following: Annotate the book. Tips for annotation: Avoid the use of highlighters. Underline key words or phrases and memorable sentences or passages. Identify unfamiliar words Write questions in the margins about something you don’t understand Mark and comment on characters and ideas that you find intriguing Note the use of literary devices Make connections to other texts, your life, your world, etc. Consider how the book deals with the following topics: Friendship Rebellion Freedom Justice Courage Arrogance Loyalty Ignorance Pay attention to the quotations at the beginning of each chapter. They come from primary sources. A primary source refers to first-hand information that was created at the time of an event. Primary sources can be newspaper articles, speeches, court documents, letters, etc. In her book, Laurie Halse Anderson uses excerpts from primary sources to foreshadow the plot, add historical context, or contrast the plot and history. Within the first two weeks of school, you will use Chains to accomplish the following objectives: participate in a Socratic discussion of the book construct a theme statement for the book identify at least three pieces of textual support for the theme statement learn how to incorporate the textual support document the textual evidence write an in-class essay, adhering to MLA style and meeting the expectations of a rubric Keep learning as you enjoy your summer break! “Reading is always an act of empathy. -

ORANGE IS the NEW BLACK Season 1 Cast List SERIES

ORANGE IS THE NEW BLACK Season 1 Cast List SERIES REGULARS PIPER – TAYLOR SCHILLING LARRY BLOOM – JASON BIGGS MISS CLAUDETTE PELAGE – MICHELLE HURST GALINA “RED” REZNIKOV – KATE MULGREW ALEX VAUSE – LAURA PREPON SAM HEALY – MICHAEL HARNEY RECURRING CAST NICKY NICHOLS – NATASHA LYONNE (Episodes 1 – 13) PORNSTACHE MENDEZ – PABLO SCHREIBER (Episodes 1 – 13) DAYANARA DIAZ – DASCHA POLANCO (Episodes 1 – 13) JOHN BENNETT – MATT MCGORRY (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) LORNA MORELLO – YAEL MORELLO (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13) BIG BOO – LEA DELARIA (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) TASHA “TAYSTEE” JEFFERSON – DANIELLE BROOKS (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13) JOSEPH “JOE” CAPUTO – NICK SANDOW (Episodes 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) YOGA JONES – CONSTANCE SHULMAN (Episodes 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) GLORIA MENDOZA – SELENIS LEYVA (Episodes 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13) S. O’NEILL – JOEL MARSH GARLAND (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13) CRAZY EYES – UZO ADUBA (Episodes 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) POUSSEY – SAMIRA WILEY (Episodes 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13) POLLY HARPER – MARIA DIZZIA (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12) JANAE WATSON – VICKY JEUDY (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) WANDA BELL – CATHERINE CURTIN (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13) LEANNE TAYLOR – EMMA MYLES (Episodes 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) NORMA – ANNIE GOLDEN (Episodes 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13) ALEIDA DIAZ – ELIZABETH RODRIGUEZ