Crime and the Soldier Identifying a Soldier-Specific Experience Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clarecastle and Ballyea in the Great War

Clarecastle and Ballyea in the Great War By Ger Browne Index Page : Clarecastle and Ballyea during the Great War Page : The 35 Men from Clarecastle and Ballyea who died in the Great War and other profiles Page 57 : The List of those from Clarecastle and Ballyea in the Great War Page : The Soldiers Houses in Clarecastle and Ballyea Page : The Belgian Refugees in Clarecastle. Page : Clarecastle and Ballyea men in WW2 1 Clarecastle and Ballyea During the Great War Ennis Road Blacksmith Power’s Pub Military Barracks Train Station Main Street RIC Barracks Creggaun Clarecastle Harbour I would like to thank Eric Shaw who kindly gave me a tour of Clarecastle and Ballyea, and showed me all the sites relevant to WW1. Eric’s article on the Great War in the book ‘Clarecastle and Ballyea - Land and People 2’ was an invaluable source of information. Eric also has been a great help to me over the past five years, with priceless information on Clare in WW1 and WW2. If that was not enough, Dr Joe Power, another historian from Clarecastle published his excellent book ‘Clare and the Great War’ in 2015. Clarecastle and Ballyea are very proud of their history, and it is a privilege to write this booklet on its contribution to the Great War. 2 Main Street Clarecastle Michael McMahon: Born in Sixmilebridge, lived in Clarecastle, died of wounds 20th Aug 1917 age 25, Royal Dublin Fusiliers 1st Bn 40124, 29th Div, G/M in Belgium. Formerly with the Royal Munster Fusiliers. Son of Pat and Kate McMahon, and husband of Mary (Taylor) McMahon (she remained a war widow for the rest of her life), Main Street, Clarecastle. -

A History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference To

The History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference to the Command of Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier by Michael Anthony Taylor A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract 119 Brigade, 40th Division, had an unusual origin as a ‘left-over’ brigade of the Welsh Army Corps and was the only completely bantam formation outside 35th Division. This study investigates the formation’s national identity and demonstrates that it was indeed strongly ‘Welsh’ in more than name until 1918. New data on the social background of men and officers is added to that generated by earlier studies. The examination of the brigade’s actions on the Western Front challenges the widely held belief that there was an inherent problem with this and other bantam formations. The original make-up of the brigade is compared with its later forms when new and less efficient units were introduced. -

Westmorland Gazette World War One Soldiers Index

Westmorland Gazette WW1 soldiers Page & Surname Forename Rank age Regiment Number Photo Address Date & Place Reason Date Column Extra Information 1000 men regiments mostly recorded North Westmorland Enlisted men,alphabetical order 03/07/1915 P4 A-E 1200 men enlisted not recorded Kendal Enlisted men,alphabetical order 22/05/1915 P4A-F 158 men Ambleside All men enlisted in Lake District 05/06/1915 4A 179 men Windermere,Bowness &Winster All men enlisted in Lake District 05/06/1915 4B 200 men Troutbeck,Grasmere & Langdale All men enlisted in Lake District 05/05/1915 4C 200 men Troutbeck,Grasmere & Langdale All men enlisted in Lake District 05/06/1915 4D 697 men listed by town/village Men enlisted in South Westmorland 12/06/1915 4A-D Abbatt Edward Leslie 2nd Air Mechanic 22 Royal Flying Corps Kendal September 8th 1917 died, cholera 22/09/1917 5d 8a details Abbott Herbert J R.G.A. Ambleside gassed 03/11/1917 3a details Abbott W R Gunner Border Regiment Crosthwaite hospitalised Salonika 02/12/1916 6b details Abraham C Sergeant 52 RAMC Crosthwaite died in hospital 28/04/1917 3b article Abraham Charles R Sergeant RAMC Crosthwaite April 20th 1917 killed France 12/05/1917 3d Dedication of Cross to the Fallen Abraham T. Private 2nd Border 19751 France Wounded 30/10/1915 5A and 24/12/1915 died of wounds Abraham Sergeant RAMC yes Crosthwaite died on service 28/04/1917 3e Abram D V Private Border Regiment 24829 Carlisle missing in action 20/01/1917 3b Ackers W.S. Private 6th Border,Mediterranean Expeditionary Force 19331 Wounded 04/09/1915 5B Ackroyd C H Captain KOYLI POW 02/12/1916 6c Old Sedberghian Sedbergh School old boy.Reported not killed POW Torgau,24/10/1914 Ackroyd Charles Harris Captain 36 Yorkshire Light Infantry Killed in action 03/10/1914 5E p7C Acton A. -

Notice. Reduction of Fees. the Average Prick of Brown Or

3913 Second Lieutenant William George Martin to be NOTICE. First Lieutenant, vice Earle. Dated 6th November, 1854. County Court? Registry, 1, Parliament-street, Westminster. Second Captain Adolphus Frederick Connell to be Captain, vice Pack-Beresford, retired by REDUCTION OF FEES. resignation of his Commission. Dated 24th THE Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty's November, 1854. Treasury have been pleased to order that the fol- First Lieutenant the Honourable Leonard Allen lowing reduced fees should be"taken for Searches, Addington to be Second Captain, vice Connell. &c., namely : Dated 24th November, 1854. Table of Fees. Second Lieutenant Philip Henry Sandilands to. s. d. be First Lieutenant, vice Addington. Dated For every search for a judgment or peti- 24th November, 1854. tion for protection made at the Registry 0 - 6 For forty searches, to be made within two months (to be paid in advance) . .10 0 For every certificate of search, obtained either through the Clerk of the Court or Commission signed by the Queen. by a letter to the Registrar 20 For having the record of any judgment City of Edinburgh Artillery Regiment of Militia. removed from the register (to be paid to Thomas Richardson Griffiths, Gent., to be Adju- the Clerk of the Court) ...... 1 6 tant. Dated 10th November, 1854. The registry of county courts' judgments was established to afford to traders a ready means of Commissions signed by the Lord Lieutenant of the ascertaining the solvency of parties, and to enable County Palatine of Lancaster. executors and administrators to discover what judgment debts they are bound to satisfy. -

WALES REGION RESEARCH Must Know Very Well Good Working Knowledge Some Familiarity Census Records Apprenticeship Records Biographical Records

IMPORTANT RECORD TYPES FOR WALES REGION RESEARCH Must Know Very Well Good Working Knowledge Some Familiarity Census Records Apprenticeship Records Biographical Records Church Records: Cemetery Records & Monumental Business Records - Church of England Inscriptions Christening Criminal Records Marriage Court Records Periodicals Burial Directories Marriage License Obituaries Allegation and Bond Emigration and Immigration Records Records Railroad Records Bishop’s Transcripts, etc. Land Records School Records Deeds -Non-Conformist Church Tax Records Tithe Applotment Christening Electoral Registers Marriage Welsh Mariners Records Burial Military Records (including Marriage License Merchant Marine) Allegation and Bond Records Newspapers Bishop’s Transcripts, etc. Parish Chest Records Civil Registrations Birth Taxation Records Marriage Death Maps and Gazetteers Probate Records STRATEGIES & RESOURCES SPECIFIC TO WALES REGION RESEARCH Know where to find and how to use the records needed to solve the client’s research problem. To learn about resources for WALES, check out the following online sites: Cyndi’s List: Categories for WALES FamilySearch Family History Research Wiki: “Wales Genealogy” Facebook: use search to find titles specific to WALES. ©2016 International Commission for the Accreditation of Professional Genealogist, ICAPGen. All Rights Reserved. National Library of Wales GENUKI, UK & Ireland Genealogy Welsh language websites Your Favorite Search Engine Use original records, whenever possible, created at the time of the event. These might be found at various jurisdictional levels (such as parish, town, county, national). Many records are available online. See FamilySearch Family History Research Wiki, Wales Online Genealogy Records for suggestions. Know how to find Non-Conformists in Wales Church of England records. Must know the Patronymic Naming Systems very well. -

Owls 2019 07

'e-Owls' Branch Website: https://oldham.mlfhs.org.uk/ MLFHS homepage : https://www.mlfhs.org.uk/ Email Chairman : [email protected] Emails General : [email protected] Email Newsletter Ed : [email protected] MLFHS mailing address is: Manchester & Lancashire Family History Society, 3rd Floor, Manchester Central Library, St. Peter's Square, Manchester, M2 5PD, United Kingdom JULY 2019 MLFHS - Oldham Branch Newsletter Where to find things in the newsletter: Oldham Branch News : ............... Page 2 From the E-Postbag : ................... Page 13 Other Branch Meetings : ............. Page 5 Peterloo Bi-Centenary : ................ Page 14 MLFHS Updates : ....................... Page 6 Need Help! : ................................. Page 16 Societies not part of MLFHS : ..... Page 9 Useful Website Links : ................. Page 18 'A Mixed Bag' : .............................Page 10 For the Gallery : ........................... Page 19 Branch News : Following April's Annual Meeting of the MLFHS Oldham Branch : Branch Officers for 2019 -2020 : Chairman : Linda Richardson Treasurer : Gill Melton Secretary & Webmistress : Jennifer Lever Newsletter Editor : Sheila Goodyear Technical Support : Rod Melton Chairman's remarks : Just to say that I hope everyone has a good summer and we look forward to seeing as many people as possible at our next meeting in September, in the Performance Space at Oldham Library. Linda Richardson Oldham Branch Chairman email me at [email protected] ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Editor's remarks. Hi Everyone, I just cannot believe how this year is running away ... as I start compiling this copy of the newsletter, we're just 1 week away from the longest day! I don't feel as if summer has even started properly yet! You'll find a new section added to the newsletter this month, which I have called, 'From the E- Postbag'. -

Searching Irish Records for Your Ancestors

Searching Irish Records For your Ancestors by Dennis Hogan Rochester NY Chapter Irish American Cultural Institute http://www.rochesteriaci.org/ © Copyright 2018 Rochester NY Chapter Irish American Cultural Institute, under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 Unported License. Searching Irish Records for Your Ancestors page 2 Many of us have a goal of tracing our families back to Ireland. It's very important to do your homework in US records BEFORE trying to identify your Irish immigrant in Irish records. (See Searching US Records for Your Irish Ancestors at http://www.rochesteriaci.org/) What’s the problem with searching Irish records? Irish records usually require knowledge of specific geographic info for your family (County NOT enough). o Solution: Use US records to discover specific geographic info for your family in Ireland All Irish families seem to use the same group of names for their children. o Solution: Use US records to develop a knowledge base of “identifiers” about your family and especially your immigrant ancestor. Encouraging Signs on the Irish Genealogy Front o Ireland Reaching Out, an Ireland-wide network of volunteers researching diaspora http://www.irelandxo.com/home. o February 2015 report of the Joint Committee on Environment, Culture, and the Gaeltacht, http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/Committee-Report-on-Genealogy.pdf o 1926 Irish Census might possibly be made available soon rather than in 2026 as the current law requires. o Community initiatives to generate tourism such as making -

Stjohns Memorial List.Pdf

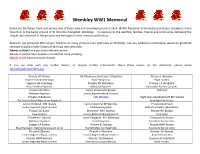

Wembley WW1 Memorial Below are the Name, Rank and Service Unit of those who are remembered on the 1914-18 War Memorial in the dedicated chapel, elsewhere in the Church or in the burial ground of St John the Evangelist, Wembley. In response to the sacrifice, families, friends and community dedicated the Chapel, the memorial in the grounds and the organ to their memory and honour. Research has produced War Service histories of many of these men with links to Wembley, but any additional information would be gratefully received to build a fuller history of the local men who died. Names in black have positively defined records. Names in purple have possible records that need verifying. Names in red have no found records. If you can help with any further details, or require further information about those names on the memorial, please email [email protected] Private AT Archer Air Mechanic 2nd Class TJ Basford Private J Bowden Royal Army Ordnance Corps Royal Flying Corps Royal Fusiliers Captain GA Armitage Private AD Batchelor Private LF Braddick West Yorkshire Regiment Middlesex Regiment Honourable Artillery Company Private FW Athis Lance Corporal H Batten H Brand Middlesex Regiment London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers) Private JT Badcock CW Bentley Flight Sub-Lieutenant CH Brinsmead The Queen's (Royal West Surrey Regiment) Royal Naval Air Service Lance Corporal OM Bailey Lance Corporal GH Bentley Private CA Brown London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers) Middlesex Regiment Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry Private CA Baker Drummer RJH Belcher Private -

Pro Patria Commemorating Service

PRO PATRIA COMMEMORATING SERVICE Forward Representative Colonel Governor of South Australia His Excellency the Honorable Hieu Van Le, AO Colonel Commandant The Royal South Australia Regiment Brigadier Tim Hannah, AM Commanding Officer 10th/27th Battalion The Royal South Australia Regiment Lieutenant Colonel Graham Goodwin Chapter Title One Regimental lineage Two Colonial forces and new Federation Three The Great War and peace Four The Second World War Five Into a new era Six 6th/13th Light Battery Seven 3rd Field Squadron Eight The Band Nine For Valour Ten Regimental Identity Eleven Regimental Alliances Twelve Freedom of the City Thirteen Sites of significance Fourteen Figures of the Regiment Fifteen Scrapbook of a Regiment Sixteen Photos Seventeen Appointments Honorary Colonels Regimental Colonels Commanding Officers Regimental Sergeants Major Nineteen Commanding Officers Reflections 1987 – 2014 Representative Colonel His Excellency the Honorable Hieu Van Le AO Governor of South Australia His Excellency was born in Central Vietnam in 1954, where he attended school before studying Economics at the Dalat University in the Highlands. Following the end of the Vietnam War, His Excellency, and his wife, Lan, left Vietnam in a boat in 1977. Travelling via Malaysia, they were one of the early groups of Vietnamese refugees to arrive in Darwin Harbour. His Excellency and Mrs Le soon settled in Adelaide, starting with three months at the Pennington Migrant Hostel. As his Tertiary study in Vietnam was not recognised in Australia, the Governor returned to study at the University of Adelaide, where he earned a degree in Economics and Accounting within a short number of years. In 2001, His Excellency’s further study earned him a Master of Business Administration from the same university. -

W.I.S.E. Newsletter

W.I.S.E. Newsletter Volume I Issue 5 SepOct 1999 Programs all day workshop on preparing for the W.I.S.E. research trip to Salt Lake City in by James K Jeffrey, programs chair January of 2000. Presentations will focus on Library Orientation, International Genealogi- Scottish and English Census cal Index, Understanding the Family History Research, featuring Ann Lisa Pearson. Library Catalog, and Major British Resources Saturday, 25 September 1999, 1:30 to 4 PM. and Indexes at the Library. $5.00 materials fee. It is imperative that you prepare before going Ann Lisa Pearson is a triple crown gal. She is to The Library in Salt Lake City. This is our president of W.I.S.E., Columbine Historical second orientation workshop. This is your and Genealogical Society and ISBGFH, the opportunity to get ready to go! International Society for British Genealogy and Family History. A frequent lecturer and Both events above are open to the public, instructor, Pearson attended the Institute for reservations are not required. Both will be Genealogy and Historical Research at Sam- held in the Lower Level Conference Center of ford University in Birmingham, Alabama this the Central Denver Public Library, 10 West summer to hone her skills in advanced re- Fourteenth Avenue Parkway. search methOdologies. She was program chair for the NGS Conference in the States "Rocky For additional information, please leave a Mountain Rendezvous" in 1998. She present- message at 303-640-6325. ed two lectures at the Federation of Genealog- ical Societies national conference in St. Louis in August. She will introduce us to nineteenth This issue includes: century Scottish and English Census records with tips on how to access, use and interpret Program: Scottish and English Census them. -

Useful Websites for Family History Research

Jersey Archive Information Leaflets Useful Websites For Family History Research The purpose of the Jersey Archive is to identify, select, www.bmdregisters.co.uk - BMD Registers is the collect, manage, preserve and provide access to the Starting Family History Official Non-Parochial on-line service for records of birth, Island’s Records on behalf of the whole community, promoting Jersey’s culture, heritage and sense of place, The following websites include useful information and baptism, marriage, death and burial taken from non- both within its shores and beyond. advice from the experts for individuals starting their parish sources. The site is extremely useful if you have UK Family History. Methodist, Baptist, or other Non Conformist Ancestors. Jersey Archive, Clarence Road, St Helier, JE2 4JY Reception: +44 (0)1534 833300 • www.bbc.co.uk/history/familyhistory http://www.britishorigins.com/ - British Origins Fax: +44 (0)1534 833101 • www.sog.org.uk/leaflets/leaflets.shtml offers access to England and Wales Gazetteer maps, E-mail: [email protected] • www.ffhs.org.uk/tips/first.php burial records, court depositions, apprenticeship Internet: www.jerseyheritage.org • www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/gettingstarted records and wills. Opening Hours: 9am to 5pm, Tuesday to Thursday. http://www.thegenealogist.co.uk/ - The The Reading Room and Help Desk are closed between www.genuki.org.uk - Genuki is a great starting Genealogist is a general family history website with 1-2pm. Late night till 7pm the last Thursday of the point for family historians. It has links to thousands of searchable databases that include Census records, month, Saturday opening on the third Saturday of the websites and is arranged by area of country. -

Improving Your Welsh Research Using Place-Names, Maps, and Gazetteers Gwella Elch Cymraeg Defnyddio Enwau Lleoedd, Mapiau, a Rhestrau

Improving your Welsh Research Using Place-names, Maps, and Gazetteers Gwella elch Cymraeg Defnyddio Enwau Lleoedd, Mapiau, a Rhestrau Dan Poffenberger, AG® British Research Consultant ~ Family History Library [email protected] Introduction I hope the above translation is correct because I used http://translate.gooqle.com to translate it. It often works well enough. Because the records used to do Welsh research are often the same as those used to do English research, the peculiarities to Welsh research can be over-looked. Anyone who has done even a little research in Wales knows that one thing, in particular, makes Welsh research more difficult than most English research, and that is the commonness of the surnames. While this class is not about the Welsh patronymic naming system, it cannot be overstated that in order to solve many Welsh research problems, every clue needs to be utilized to full advantage. In this case, understanding the place where your Welsh ancestor lived is often one of those important clues. Because many people in the same parish had the same name (such as John Thomas), the Welsh often used farm names or birthplaces to identify themselves (John Thomas of Pen-y-Benglog). One other aspect that can make Welsh research difficult specifically when it comes to places is that the same place-name can be used many times in various parts of Wales. A gazetteer can help you identify the most common spellings and the counties that have a place by that name. Also, spellings vary widely in Welsh place-names. Objectives By the end of this class, you will be able to: 1) Identify the counties and parishes of Wales 2) Understand the role of farm names, small hamlets, manors, and estates in your research 3) Find the description of these places in gazetteers 4) Find these places on maps Identifying the Counties and Parishes of Wales When working from home, the best way to gain an understanding of Wales' counties is the FamilySearch Wiki (http://wiki.familysearch.org).