Training for Packing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frecker's Saddlery

Frecker’s Saddlery Frecker’s 13654 N 115 E Idaho Falls, Idaho 83401 addlery (208) 538-7393 S [email protected] Kent and Dave’s Price List SADDLES FULL TOOLED Base Price 3850.00 5X 2100.00 Padded Seat 350.00 7X 3800.00 Swelled Forks 100.00 9X 5000.00 Crupper Ring 30.00 Dyed Background add 40% to tooling cost Breeching Rings 20.00 Rawhide Braided Hobble Ring 60.00 PARTIAL TOOLED Leather Braided Hobble Ring 50.00 3 Panel 600.00 5 Panel 950.00 7 Panel 1600.00 STIRRUPS Galvanized Plain 75.00 PARTIAL TOOLED/BASKET Heavy Monel Plain 175.00 3 Panel 500.00 Heavy Brass Plain 185.00 5 Panel 700.00 Leather Lined add 55.00 7 Panel 800.00 Heel Blocks add 15.00 Plain Half Cap add 75.00 FULL BASKET STAMP Stamped Half Cap add 95.00 #7 Stamp 1850.00 Tooled Half Cap add 165.00 #12 Stamp 1200.00 Bulldog Tapadero Plain 290.00 Bulldog Tapadero Stamped 350.00 PARTIAL BASKET STAMP Bulldog Tapadero Tooled 550.00 3 Panel #7 550.00 Parade Tapadero Plain 450.00 5 Panel #7 700.00 Parade Tapadero Stamped (outside) 500.00 7 Panel #7 950.00 Parade Tapadero Tooled (outside) 950.00 3 Panel #12 300.00 Eagle Beak Tapaderos Tooled (outside) 1300.00 5 Panel #12 350.00 7 Panel #12 550.00 BREAST COLLARS FULL BASKET/TOOLED Brannaman Martingale Plain 125.00 #7 Basket/Floral Pattern 2300.00 Brannaman Martingale Stamped 155.00 #12 Basket/Floral 1500.00 Brannaman Martingale Basket/Tooled 195.00 Brannaman Martingale Tooled 325.00 BORDER STAMPS 3 Piece Martingale Plain 135.00 Bead 150.00 3 Piece Martingale Stamped 160.00 ½” Wide 250.00 3 Piece Martingale Basket/Tooled 265.00 -

Pocket Packing Guide You Will Find the Following Information

ABOUT LLAMAS Llamas Colorado LLC Llamas are superior pack animals. They are quiet, courteous, curious, intelligent, strong and agile. POCKET Llamas have soft pads on the bottom of their foot like a dog. This PACKING is optimal in helping to reduce environ- mental impact. They have two toes that GUIDE operate independ- ently, which makes This little guidebook should serve as a quick them very surefooted and easy to pack on reference - just in case you can't remember rough terrain. They are also very clean. every detail learned at orientation. They tend to go to the bathroom in the same spots if they John & Devin have been there before. We are so pleased that you have chosen us to help make your trip enjoyable, stress-free, and environmentally harmonious. We want you to enjoy our llamas as much as we do, and that involves knowing how to handle them on and off the trail. In this Pocket Packing Guide you will find the following information: Introduction . .1 About Llamas . .3 Preparing for your pack trip . .6 General Handling . .6 Loading the Panniers . .7 At the Trailhead . .7 Saddling . .8 On the Trail . .10 Trail Circumstances . .12 Meetings on the Trail . .14 Difficulties on the Trail . .14 Camp Time . .16 Llama on the Loose . .18 First Aid Kit for Llamas . .19 Do's & Don'ts quick reference list . .19 Knots . 21 Frequently asked questions . 23 Hello! Welcome Many thanks to Al & Sonora Ellis, Cindy Campbell, Elisabeth Myers, MJ Myers, Denise Newberry, and Katy to Thach for help with this booklet. -

Freewheeling12-SCREE

These bags have many imitators but Inner city cycles Karrimor is the original. Models include D Iberian pannier ( top of the range) D Standard rear panniers, available in red nylon or green cotton canvas D Univer TIie one stop touring shop sal pannier. Usable as front or rear bags./ D Front pannier in red nylon or green cotton canvas D Bardale and Bartlet handlebar bags D Pannier stuff sacks D Front and rear pannier racks D Re bikes are always available. Other items placement parts and repairs available. stocked are D Safety gear, helmets, C1cleTour vests, flags D Camping accessories D Bicycle accessories D Racks D At Inner City we build most of our Parkas and Capes . In fact anything you touring bicycles to order. Seldom two need to make your bicycle expedition bicycles are the same as each person has an enjoyable experience you will pro their own requirements. Our Cycle Tour bably find at Inner City Cycles. bicycles are not just another production machine. OPTION TWO • Price $320. Pt1dtlymt1de This bicycle is the ideal touring machine for a moderate financial outlay. Wide range gearing is made possible by the addition of Shimano 600 gears. Specifica tion: D Frame sizes as for option 1 also with guarantee D Alloy handle bars and recessed bolt stem D Cloth tape D Sugino or Suntour cotterless chain wheel set. Ring sizes 36-52 D Alloy We stock a wide range of quality Paddy pedals with reflectors D Shimano 600 EX made equipment made especially for front derailleur, 600 GS (long arm) rear Australian conditions. -

Harness Fitting Guide

HARNESS FITTING GUIDE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The input of the following people is greatly appreciated in providing information for compiling this evolving guide Dr. Solomon Onyango Amos Parsimei Daniel Mukoma John Maina Nicolas Mungiria Compiled by Dr. David Obiero Nairobi, Kenya The Donkey Sanctuary Kenya, 2013 Table of Contents HARNESS EQUIPMENT ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 HARNESS FITTING ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 FITTING THE KASUKU HARNESS ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 FITTING THE PACK SADDLE/PANNIER ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 15 2 HARNESS EQUIPMENT PARTS OF THE WEB BLOCK HARNESS AND KASUKU HARNESS BLOCK SADDLE &GIRTH STRAP BREECH STRAP BREAST- COLLAR AND TRACES BELLY BAND BACK PROTECTOR KASUKU HARNESS HALTER PACK SADDLE/PANNIER 3 HARNESS FITTING THE WEB-BLOCK HARNESS STEP -

Leave No Trace: Outdoor Skills and Ethics- Backcountry Horse

Leave No Trace: Outdoor Skills and Ethics Backcountry Horse Use The Leave No Trace program teaches and develops practical conservation techniques designed to minimize the "impact" of visitors on the wilderness environment. "Impact" refers to changes visitors create in the backcountry, such as trampling of fragile vegetation or pollution of water sources. The term may also refer to social impacts-- behavior that diminishes the wilderness experience of other visitors. Effective minimum-impact practices are incorporated into the national Leave No Trace education program as the following Leave No Trace Principles. Principles of Leave No Trace · Plan Ahead and Prepare · Concentrate Use in Resistant Areas · Avoid Places Where Impact is Just Beginning · Pack It In, Pack It Out · Properly Dispose of What You Can't Pack Out · Leave What You Find · Use Fire Responsibly These principles are a guide to minimizing the impact of your backcountry visits to America's arid regions. This booklet discusses the rationale behind each principle to assist the user in selecting the most appropriate techniques for the local environment. Before traveling into the backcountry, we recommend that you check with local officials of the Forest Service, Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management or other managing agency for advice and regulations specific to the area you will be traveling in. First and foremost, it is important to carefully review and follow all agency regulations and recommendations; these materials support and complement agency guidelines .Minimizing our impact on the backcountry depends more on attitude and awareness than on rules and regulations. Leave No Trace camping practices must be flexible and tempered by judgment and experience. -

Cabinet BCH of Montana Natural Equine Care Clinic by Deena Shotzberger, President

Volume 26, Issue 3 www.bcha.org Summer 2015 Cabinet BCH of Montana Natural Equine Care Clinic By Deena Shotzberger, President BCHA Education Grants at Work in Montana Left: Cindy Brannon demonstrating a boot fit on Dr. Oedekoven’s horse, Sonny. Below: Jim Brannon discussing and trim- ming Jenny Holifield’s Arabian, John Henry. Thanks to a grant from the BCH ed to offer a more complete approach hoof’s role and function Education Foundation, Cabinet BCH to hoof care for consideration (regard- • Assessing the health of hooves hosted a clinic with Dr. Amanda Oede- less of whether animals were shod or • Why proper hoof care and koven, veterinarian; Jim Brannon, nat- barefoot). Many hoof problems can living conditions can lead to a longer ural hoof care practitioner; and Cindy be avoided by following better nutri- working life for your horse, and why Brannon, hoof boot specialist in Libby, tion, exercise and environment, and a this is critical in young growing horses MT on March 21. This was a great op- more holistic method of hoof care. The • The difference between a shoe- portunity for 23 equine owners in our clinic offered participants information ing trim and a barefoot trim and how small community to learn about nutri- on how to lower the risk for navicular, the differences improve the health of tion, exercise and environment; anato- laminitis, and insulin resistance. Par- your horses’ hooves my and function of the lower leg and ticipants learned how to provide their • How to spot and address im- hoofs; hoof care and trimming prin- horse a healthier and fitter life through balances in the hoof before they cause ciples. -

A Comprehensive Guide to Llama Packing

A Comprehensive Guide to Llama Packing 2 Contents Forward...................................................................................................................................................... 5 1. About the Llamas ................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Llama Handling ...................................................................................................................................... 9 3. Llama LNT ........................................................................................................................................... 13 4. Prior to Trailhead ................................................................................................................................. 14 5. At the Trailhead ................................................................................................................................... 19 6. On the Trail .......................................................................................................................................... 27 7. At Camp ............................................................................................................................................... 33 8. Llama 1st Aid ....................................................................................................................................... 37 9. Troubleshooting .................................................................................................................................. -

Preparation, Planning, & Knowledge

PREPARATION, PLANNING, & KNOWLEDGE Packhorses help carry you into adventure but require user horse sense Dusty Smith • Manty – large piece of canvas Shorter days and the crisp in used to cover and secure load the air mean one thing in our family: hunting is just around the corner. Pack Saddles Types Packing into Wyoming wilderness There are two different styles areas can be done on foot, but we of pack saddles – the traditional choose to use our horses to take us “Sawbuck,” which has two distinct on adventures. looking “X’s” made of wood on top, Horses can be very useful when and the “Decker,” which consists of carrying loads into the backcountry two metal bars shaped into oblong but can be a big commitment initially hoops. Sawbucks use a single rope to purchase equipment and prepare. attached to a lash cinch to hitch There is essential equipment loads, and Deckers use two ropes needed for packing horses: attached at the metal hoops to sling • Pack saddle – saddle made for loads. The two pack styles carry packing loads the same load – just a little differ- ently. Each can use panniers, but • Pack saddle pad – larger than the Decker-style packs have become regular saddle pad popular because of their versatility in • Lash cinch – strip of material with packing odd-shaped loads. a ring on one end and a hook on Planning and preparation are the other. A 20- to 50-foot rope is a must to ensure proper load size, tied to the ring end and used to placement, and adequate number of attach the load. -

Packing with Horses & Mules

Back Country Horsemen of Montana PACKING WITH HORSES & MULES Horsemen’s Creed—When I ride out of the mountains, I’ll leave only hoof prints, take only memories. The purpose of this packing booklet is to provide basic information in an organized manner to help you learn about horses and equipment and to effectively plan and take pack trips in the back country. Use of qualified persons to help with the teaching of packing fundamentals and back country safety will make packing easier and more fun. Packing as a hobby, or as a business, can be very enjoyable with the proper equipment, a basic knowledge of the horse, good camping equipment, a sound trip itinerary, well-thought-out menus, and other details will help to make a well-rounded pack trip. The Back Country Horsemen of Montana is dedicated to protecting, preserving and improving the back country resource by volunteering time and equipment to government agencies for such tasks as clearing trails, building trails, building trailhead facilities, packing out trash and other projects that will benefit both horsemen and non-horsemen. Mission Statement To perpetuate the common sense use and enjoyment of horses in America’s back country, roadless backcountry and wilderness areas; To work to ensure that public lands remain open to recreational stock use; To assist the various government and private agencies in their maintenance and management of said resource; To educate, encourage and solicit active participation by the general public in the wise and sustaining use of the back country resource by horses and people commensurate with our heritage; To foster and encourage the formation of new state back country horsemen organizations; To seek out opportunities to enhance existing areas of recreation for stock users. -

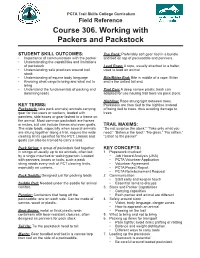

Course 306. Working with Packers and Packstock

PCTA Trail Skills College Curriculum Field Reference Course 306. Working with Packers and Packstock STUDENT SKILL OUTCOMES: Top Pack: Preferably soft gear tied in a bundle • Importance of communication with the packer and tied on top of packsaddle and panniers. • Understanding the capabilities and limitations of packstock Lead Rope: A rope, usually attached to a halter, • Understanding safe practices around trail used to lead an animal stock • Understanding of equine body language Bite/Bitter End: Bite is middle of a rope. Bitter • Knowing what cargo to bring and what not to end is the untied tail end. bring • Understand the fundamentals of packing and Tool Can: A deep narrow plastic trash can balancing loads adapted for use hauling trail tools via pack stock. Highline: Rope strung tight between trees. KEY TERMS: Packstock are then tied to the highline instead Packstock: (aka pack animals) animals carrying of being tied to trees, thus avoiding damage to gear for trail users or workers, loaded with trees. panniers, side boxes or gear lashed to a frame on the animal. Most common packstock are horses or mules, but can include llamas and even goats. TRAIL MAXIMS: The wide loads, especially when several animals “Do not surprise the stock,” “Take only what you are strung together along a trail, require the wide need,” “Balance the load,” “No glass,” “No rattles,” clearing limits specified for the PCT. Llamas and “Listen to the packer” goats can also be trained to carry a load. Pack String: a group of packstock tied together KEY CONCEPTS: in strings of usually up to six animals, often led 1. -

2015 Adventure Proof Packing Systems

Photo by David Schelske, www.davidschelske.com. We want you to be 100% stoked with your Giant Loop 2015 ADVENTURE PROOF purchase — and if you’re not, we need to hear about it, so we can make things right for you. Giant Loop provides to the original purchaser a limited PACKING SYSTEMS lifetime warranty against defects in materials or craftsmanship if purchased FOR MOTORCYCLES directly from a Giant Loop authorized dealer. This warranty covers defective materials and craftsmanship only, and does not include damage due to normal wear and tear or misuse. Failure to comply with the included instructions for this Product will void the limited lifetime warranty. If defects in the materials or craftsmanship of the Product exist, notify Giant Loop immediately of the defect. Giant Loop will provide for repair or replacement of the Product, after Giant Loop has determined, in our sole discretion, that a defect is present. Proof of purchase is required to utilize the limited warranty provisions. If you experience any problems with the Product within the warranty period please return the Product or contact us for prompt repair or replacement at our discretion. DESIGNED IN BEND, OREGON. MADE IN USA. RIDDEN WORLDWIDE. www.giantloopmoto.com 458-206-9113 GO LIGHT. GO FAST. GO FAR. [email protected] 2014 Giant Loop Adventure Proof Packing Systems Primary Application* Color / Dimensions (in.) Dirt Bike Adventure Bike Page Product Name Part # Description Size Options Total Volume (liters) Waterproof Weight (lbs) (H x L x W in.) (no passenger pegs) (passenger pegs) SADDLEBAG & PANNIER SYSTEMS Coyote Saddlebag For multi-day trips on dirt/dual sport bikes. -

Tusk Pannier Racks Instructions and Information KLR650 1987-2007

Tusk Pannier Racks Instructions and information KLR650 1987-2007 Congratulations on your purchase of the Tusk Pannier Racks. These racks are made to handle extreme adventure riding, but work great for the commuter as well. Please take note of the information and instructions below to get the most out of your Tusk racks and panniers. Note: For instructional videos, refer to www.rockymountainatvmc/videos . Assembly : Before you throw any packaging away, make sure you received all the necessary hardware: Rack hardware Box mounting hardware 8mm x 35mm bolt (2) M8 x 20mm plastic lock knob (2) 8mm x 40mm bolt (2) 8mm externally serrated washer (2) 8mm x 55mm bolt (2) 8mm x 25mm button head allen bolt (8) 8mm x 1.25mm flange nut (2) 8mm x 20mm button head allen bolt (6) 6mm x 20mm bolt (4) 8mm x 1.25 hex flange nut (14) 6mm x 1.00mm lock nut (4) 8mm flat washer (22) Blinker wire extension kit (1) Turn signal spacer (2) Rack parts Left side rack with box mount ring (1) Right side rack with box mounting ring (1) Rear rack brace (1) Blinker extension right (1) Blinker extension left (1) Internal Box support flat bar (2) Rack Installation 1. Remove stock upper bolt on both the left and right passenger foot peg. 2. Remove Rear blinkers from the rear rack – unplug from bike. 3. Remove the 8mm mounting bolt on both the left and right side of the stock rear rack. 4. Remove the helmet lock from the rear rack (it will be easier to access the bolts by removing the rear rack entirely).