A Comprehensive Guide to Llama Packing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frecker's Saddlery

Frecker’s Saddlery Frecker’s 13654 N 115 E Idaho Falls, Idaho 83401 addlery (208) 538-7393 S [email protected] Kent and Dave’s Price List SADDLES FULL TOOLED Base Price 3850.00 5X 2100.00 Padded Seat 350.00 7X 3800.00 Swelled Forks 100.00 9X 5000.00 Crupper Ring 30.00 Dyed Background add 40% to tooling cost Breeching Rings 20.00 Rawhide Braided Hobble Ring 60.00 PARTIAL TOOLED Leather Braided Hobble Ring 50.00 3 Panel 600.00 5 Panel 950.00 7 Panel 1600.00 STIRRUPS Galvanized Plain 75.00 PARTIAL TOOLED/BASKET Heavy Monel Plain 175.00 3 Panel 500.00 Heavy Brass Plain 185.00 5 Panel 700.00 Leather Lined add 55.00 7 Panel 800.00 Heel Blocks add 15.00 Plain Half Cap add 75.00 FULL BASKET STAMP Stamped Half Cap add 95.00 #7 Stamp 1850.00 Tooled Half Cap add 165.00 #12 Stamp 1200.00 Bulldog Tapadero Plain 290.00 Bulldog Tapadero Stamped 350.00 PARTIAL BASKET STAMP Bulldog Tapadero Tooled 550.00 3 Panel #7 550.00 Parade Tapadero Plain 450.00 5 Panel #7 700.00 Parade Tapadero Stamped (outside) 500.00 7 Panel #7 950.00 Parade Tapadero Tooled (outside) 950.00 3 Panel #12 300.00 Eagle Beak Tapaderos Tooled (outside) 1300.00 5 Panel #12 350.00 7 Panel #12 550.00 BREAST COLLARS FULL BASKET/TOOLED Brannaman Martingale Plain 125.00 #7 Basket/Floral Pattern 2300.00 Brannaman Martingale Stamped 155.00 #12 Basket/Floral 1500.00 Brannaman Martingale Basket/Tooled 195.00 Brannaman Martingale Tooled 325.00 BORDER STAMPS 3 Piece Martingale Plain 135.00 Bead 150.00 3 Piece Martingale Stamped 160.00 ½” Wide 250.00 3 Piece Martingale Basket/Tooled 265.00 -

Public Auction

PUBLIC AUCTION Mary Sellon Estate • Location & Auction Site: 9424 Leversee Road • Janesville, Iowa 50647 Sale on July 10th, 2021 • Starts at 9:00 AM Preview All Day on July 9th, 2021 or by appointment. SELLING WITH 2 AUCTION RINGS ALL DAY , SO BRING A FRIEND! LUNCH STAND ON GROUNDS! Mary was an avid collector and antique dealer her entire adult life. She always said she collected the There are collections of toys, banks, bookends, inkwells, doorstops, many items of furniture that were odd and unusual. We started with old horse equipment when nobody else wanted it and branched out used to display other items as well as actual old wood and glass display cases both large and small. into many other things, saddles, bits, spurs, stirrups, rosettes and just about anything that ever touched This will be one of the largest offerings of US Army horse equipment this year. Look the list over and a horse. Just about every collector of antiques will hopefully find something of interest at this sale. inspect the actual offering July 9th, and July 10th before the sale. Hope to see you there! SADDLES HORSE BITS STIRRUPS (S.P.) SPURS 1. U.S. Army Pack Saddle with both 39. Australian saddle 97. U.S. civil War- severe 117. US Calvary bits All Model 136. Professor Beery double 1 P.R. - Smaller iron 19th 1 P.R. - Side saddle S.P. 1 P.R. - Scott’s safety 1 P.R. - Unusual iron spurs 1 P.R. - Brass spurs canvas panniers good condition 40. U.S. 1904- Very good condition bit- No.3- No Lip Bar No 1909 - all stamped US size rein curb bit - iron century S.P. -

Pocket Packing Guide You Will Find the Following Information

ABOUT LLAMAS Llamas Colorado LLC Llamas are superior pack animals. They are quiet, courteous, curious, intelligent, strong and agile. POCKET Llamas have soft pads on the bottom of their foot like a dog. This PACKING is optimal in helping to reduce environ- mental impact. They have two toes that GUIDE operate independ- ently, which makes This little guidebook should serve as a quick them very surefooted and easy to pack on reference - just in case you can't remember rough terrain. They are also very clean. every detail learned at orientation. They tend to go to the bathroom in the same spots if they John & Devin have been there before. We are so pleased that you have chosen us to help make your trip enjoyable, stress-free, and environmentally harmonious. We want you to enjoy our llamas as much as we do, and that involves knowing how to handle them on and off the trail. In this Pocket Packing Guide you will find the following information: Introduction . .1 About Llamas . .3 Preparing for your pack trip . .6 General Handling . .6 Loading the Panniers . .7 At the Trailhead . .7 Saddling . .8 On the Trail . .10 Trail Circumstances . .12 Meetings on the Trail . .14 Difficulties on the Trail . .14 Camp Time . .16 Llama on the Loose . .18 First Aid Kit for Llamas . .19 Do's & Don'ts quick reference list . .19 Knots . 21 Frequently asked questions . 23 Hello! Welcome Many thanks to Al & Sonora Ellis, Cindy Campbell, Elisabeth Myers, MJ Myers, Denise Newberry, and Katy to Thach for help with this booklet. -

Freewheeling12-SCREE

These bags have many imitators but Inner city cycles Karrimor is the original. Models include D Iberian pannier ( top of the range) D Standard rear panniers, available in red nylon or green cotton canvas D Univer TIie one stop touring shop sal pannier. Usable as front or rear bags./ D Front pannier in red nylon or green cotton canvas D Bardale and Bartlet handlebar bags D Pannier stuff sacks D Front and rear pannier racks D Re bikes are always available. Other items placement parts and repairs available. stocked are D Safety gear, helmets, C1cleTour vests, flags D Camping accessories D Bicycle accessories D Racks D At Inner City we build most of our Parkas and Capes . In fact anything you touring bicycles to order. Seldom two need to make your bicycle expedition bicycles are the same as each person has an enjoyable experience you will pro their own requirements. Our Cycle Tour bably find at Inner City Cycles. bicycles are not just another production machine. OPTION TWO • Price $320. Pt1dtlymt1de This bicycle is the ideal touring machine for a moderate financial outlay. Wide range gearing is made possible by the addition of Shimano 600 gears. Specifica tion: D Frame sizes as for option 1 also with guarantee D Alloy handle bars and recessed bolt stem D Cloth tape D Sugino or Suntour cotterless chain wheel set. Ring sizes 36-52 D Alloy We stock a wide range of quality Paddy pedals with reflectors D Shimano 600 EX made equipment made especially for front derailleur, 600 GS (long arm) rear Australian conditions. -

Harness Fitting Guide

HARNESS FITTING GUIDE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The input of the following people is greatly appreciated in providing information for compiling this evolving guide Dr. Solomon Onyango Amos Parsimei Daniel Mukoma John Maina Nicolas Mungiria Compiled by Dr. David Obiero Nairobi, Kenya The Donkey Sanctuary Kenya, 2013 Table of Contents HARNESS EQUIPMENT ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 HARNESS FITTING ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 FITTING THE KASUKU HARNESS ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 FITTING THE PACK SADDLE/PANNIER ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 15 2 HARNESS EQUIPMENT PARTS OF THE WEB BLOCK HARNESS AND KASUKU HARNESS BLOCK SADDLE &GIRTH STRAP BREECH STRAP BREAST- COLLAR AND TRACES BELLY BAND BACK PROTECTOR KASUKU HARNESS HALTER PACK SADDLE/PANNIER 3 HARNESS FITTING THE WEB-BLOCK HARNESS STEP -

MU Guide PUBLISHED by MU EXTENSION, UNIVERSITY of MISSOURI-COLUMBIA Muextension.Missouri.Edu

Horses AGRICULTURAL MU Guide PUBLISHED BY MU EXTENSION, UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI-COLUMBIA muextension.missouri.edu Choosing, Assembling and Using Bridles Wayne Loch, Department of Animal Sciences Bridles are used to control horses and achieve desired performance. Although horses can be worked without them or with substitutes, a bridle with one or two bits can add extra finesse. The bridle allows you to communicate and control your mount. For it to work properly, you need to select the bridle carefully according to the needs of you and your horse as well as the type of performance you expect. It must also be assembled correctly. Although there are many styles of bridles, the procedures for assembling and using them are similar. The three basic parts of a bridle All bridles have three basic parts: bit, reins and headstall (Figure 1). The bit is the primary means of communication. The reins allow you to manipulate the bit and also serve as a secondary means of communica- tion. The headstall holds the bit in place and may apply Figure 1. A bridle consists of a bit, reins and headstall. pressure to the poll. The bit is the most important part of the bridle The cheekpieces and shanks of curb and Pelham bits because it is the major tool of communication and must also fit properly. If the horse has a narrow mouth control. Choose one that is suitable for the kind of perfor- and heavy jaws, you might bend them outward slightly. mance you desire and one that is suitable for your horse. Cheekpieces must lie along the horse’s cheeks. -

Leave No Trace: Outdoor Skills and Ethics- Backcountry Horse

Leave No Trace: Outdoor Skills and Ethics Backcountry Horse Use The Leave No Trace program teaches and develops practical conservation techniques designed to minimize the "impact" of visitors on the wilderness environment. "Impact" refers to changes visitors create in the backcountry, such as trampling of fragile vegetation or pollution of water sources. The term may also refer to social impacts-- behavior that diminishes the wilderness experience of other visitors. Effective minimum-impact practices are incorporated into the national Leave No Trace education program as the following Leave No Trace Principles. Principles of Leave No Trace · Plan Ahead and Prepare · Concentrate Use in Resistant Areas · Avoid Places Where Impact is Just Beginning · Pack It In, Pack It Out · Properly Dispose of What You Can't Pack Out · Leave What You Find · Use Fire Responsibly These principles are a guide to minimizing the impact of your backcountry visits to America's arid regions. This booklet discusses the rationale behind each principle to assist the user in selecting the most appropriate techniques for the local environment. Before traveling into the backcountry, we recommend that you check with local officials of the Forest Service, Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management or other managing agency for advice and regulations specific to the area you will be traveling in. First and foremost, it is important to carefully review and follow all agency regulations and recommendations; these materials support and complement agency guidelines .Minimizing our impact on the backcountry depends more on attitude and awareness than on rules and regulations. Leave No Trace camping practices must be flexible and tempered by judgment and experience. -

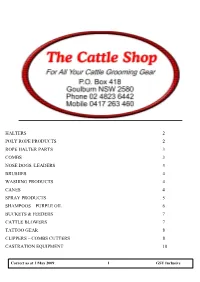

Rolled Show Cattle Halter

HALTERS 2 POLY ROPE PRODUCTS 2 ROPE HALTER PARTS 3 COMBS 3 NOSE DOGS /LEADERS 3 BRUSHES 4 WASHING PRODUCTS 4 CANES 4 SPRAY PRODUCTS 5 SHAMPOOS – PURPLE OIL 6 BUCKETS & FEEDERS 7 CATTLE BLOWERS 7 TATTOO GEAR 8 CLIPPERS – COMBS CUTTERS 8 CASTRATION EQUIPMENT 10 Correct as at 1 May 2009 1 GST Inclusive The Cattle Shop Phone 02 4823 6442 Product Catalogue www.thecattleshop.com.au Leather Cattle Lead with snap – A 1.5m strong HALTERS quality leather lead with solid brass that can be matched with any cattle halter. Australian made Rolled Available in Black or Brown Leather Halters. Black or Price $12.50 Brown Leather With brass or nickel fittings Leather Cattle Lead with Chain – nickel plated Bull – chain and snap overall length 223cm. Cow – Price $18.00 Heifer and Calf sizes. POLY ROPE PRODUCTS Price: $ 130.00 Poly Rope Halter, Neck Ties Deluxe Rolled Show Halter – INDIAN LEATHER and Lead Ropes -Made from Complete lead-in set with strong poly rope solid brass chain on lead. Available in Black, Red, Blue, Brass fittings and separate Green or Maroon brass lead and snap. Sturdy Halter - $19.95 and strong rolled leather. Available in Brown or Black / Neck Tie – Ideal for securing animals at shows. Solid Brass brass snap hook Small -Medium - Large Price 29.95 All One Price $65.00 Cattle Lead Strong poly rope lead 185cm long with solid brass Indian Leather Halter Black snap hook with Stainless steel hardware Price $17.95 and a rolled noseband comes complete with 2 stainless steel Fluro Halters – leads Small, Medium and Large Available in $84.95 Purple/Black, Pink/Black, Green/White, Green/Pink Leather Halter Brown with and Black/Orange Brass, soft and supple yet strong $15.95 these 1” brown oiled leather cattle halters have solid brass hardware Solid Colour halters – and a rolled noseband comes in Blue, Black, Purple, complete with 2 leads Green and Red. -

Bosal and Hackamores-Think Like a Horse-Rick Gore Horsemanship®

Bosal and Hackamores-Think Like a Horse-Rick Gore Horsemanship® *Home Horse's love it when their owner's understand them. *Sitemap Horsemanship is about the horse teaching you about yourself. *SEARCH THE SITE *Horse History *Horseman Tips *Horsemanship *Amazing Horse Hoof *Horse Anatomy Pictures Care and Cleaning of Bosal and Rawhide *Rope Halters No discussion of the Bosal and Hackamore would be complete My Random Horse without mentioning, Ed Connell. His books about using, starting and training with the Hackamore are from long ago and explain things Thoughts well. If you want to completely understand the Bosal and Hackamore, his books explain it in detail. *Tying A Horse Bosals and Hackamores were originally used to start colts in training. Since untrained colts make many mistakes, a hackamore *Bosal/Hackamores does not injure sensitive tissue in the colt's mouth and provides firm and safe control. The term Hackamore and Bosal are interchangeable, however, technically the *Bad Horsemanship Bosal is only the rawhide braid around the nose of the horse. The hanger and reins together with the Bosal completes the Hackamore. *Misc Horse Info Parts of a Hackamore :Hackamore came from Spanish culture and was derived from the *Trailer Loading Spanish word jaquima (hak-kee-mah). The parts of the Hackamore are: *Training Videos Bosal (boz-al):This is the part around the horse's nose usually made of braided rawhide, but it can be made of leather, horsehair or rope. The size and thickness of the *Hobbles bosal can vary from pencil size (thin) to 5/8 size (thick). -

2019 Saddleseat Horse Division

2019 SADDLESEAT HORSE DIVISION Contents General Rules Saddleseat Division Classes Saddleseat Equitation Scoring The Saddleseat Division is an Open Division, and NOT eligible for High Point awards. Classes Walk and Trot Pleasure Three-Gaited Show Pleasure Three-Gaited Country Pleasure Five-Gaited Show Pleasure Five-Gaited Country Pleasure Pleasure Equitation • Ground Handling OI: open to all breeds and disciplines. Rules are posted separately. All 4-H’ers riding or driving horses at 4-H events or activities are required to wear an ASTM-SEI Equestrian Helmet at all times. SS-1 GENERAL RULES All 4-H’ers riding or driving horses and/or ponies at 4-H events or activities are required to wear an ASTM-SEI Equestrian helmet at all times. Cruelty, abuse or inhumane treatment of any horse in the show ring or in the stable area will not be tolerated by the show management, and the offender will be barred from the show area for the duration of the show. Evidence of any inhumane treatment to a horse including but not limited to blood, whip marks that raise welts or abusive whipping, in or out of the show ring, shall result in disqualification of that horse and that exhibitor for the entire show and shall result in the forfeiture of all ribbons, awards and points won. SADDLESEAT DIVISION CLASSES WALK AND TROT PLEASURE - Entries must show in a flat, cutback English saddle with full bridle, pelham, or snaffle. Use of a standing martingale, bosal, mechanical hackamore, draw reins and/or tie down is prohibited. However, the use of a running or German martingale with only a single snaffle or work snaffle bridle is acceptable. -

Cabinet BCH of Montana Natural Equine Care Clinic by Deena Shotzberger, President

Volume 26, Issue 3 www.bcha.org Summer 2015 Cabinet BCH of Montana Natural Equine Care Clinic By Deena Shotzberger, President BCHA Education Grants at Work in Montana Left: Cindy Brannon demonstrating a boot fit on Dr. Oedekoven’s horse, Sonny. Below: Jim Brannon discussing and trim- ming Jenny Holifield’s Arabian, John Henry. Thanks to a grant from the BCH ed to offer a more complete approach hoof’s role and function Education Foundation, Cabinet BCH to hoof care for consideration (regard- • Assessing the health of hooves hosted a clinic with Dr. Amanda Oede- less of whether animals were shod or • Why proper hoof care and koven, veterinarian; Jim Brannon, nat- barefoot). Many hoof problems can living conditions can lead to a longer ural hoof care practitioner; and Cindy be avoided by following better nutri- working life for your horse, and why Brannon, hoof boot specialist in Libby, tion, exercise and environment, and a this is critical in young growing horses MT on March 21. This was a great op- more holistic method of hoof care. The • The difference between a shoe- portunity for 23 equine owners in our clinic offered participants information ing trim and a barefoot trim and how small community to learn about nutri- on how to lower the risk for navicular, the differences improve the health of tion, exercise and environment; anato- laminitis, and insulin resistance. Par- your horses’ hooves my and function of the lower leg and ticipants learned how to provide their • How to spot and address im- hoofs; hoof care and trimming prin- horse a healthier and fitter life through balances in the hoof before they cause ciples. -

Dover Saddlery® Nameplates a Personalized Nameplate Identifies Your Horse Or Pony's Tack, Stall Or SADDLE PLATES Other Equipment in Style

Dover Saddlery® Nameplates A personalized nameplate identifies your horse or pony's tack, stall or SADDLE PLATES other equipment in style. Choose from brass and German silver plates in 3 Fancy Saddle Plate - 2½" x /8" a classic or contemporary style. Each will be engraved in the USA in Brass German Silver your choice of Block, Old English, Roman or Script letters.* #32307 ............................ $10.95 3 2" Fancy Saddle Plate - 2" x /8" #32301 (Brass only) ........ $11.95 Beveled Edge Saddle Plate - 2½" x ½". #32302 (Brass only) ........ $13.95 Beveled Notched Corner Saddle Plate - 2½" x ½" #32363 (Brass only) ........ $14.95 MISCELLANEOUS PLATES HALTER PLATES Rectangular Dog Collar Plate - 2½" x ½" Rectangular Halter Plate - 4½" x ¾" #32325 (Brass only) ........ $14.95 Brass German Silver 3 1 or 2 lines ....................#32304 $15.95 Belt Nameplate - 2½" x /8" 3 lines ........................ #32316 $17.95 Brass German Silver Beveled Edge Halter Plate - 4½" x ¾" #4139 .............................. $10.95 Brass German Silver Beveled 1 or 2 lines .................. #32315 $15.95 PLASTIC NAMEPLATES 3 lines ........................ #32317 $18.95 Plastic Stall Plate - 2" x 8" Fancy Halter Plate - 4½" x ¾" With pre-drilled holes. Please specify if Brass German Silver holes are not needed. 1 or 2 lines .................. #32318 $15.95 3 lines ........................ #32319 $18.95 1 or 2 lines .................. #32306 $21.95 Notched Corner Halter Plate - 4½" x ¾" 3 lines ........................ #32327 $24.95 Brass German Silver Plastic Stall Plate With Holder 1 or 2 lines ..........................#32366 $15.95 Plate slides into gold tone holder, Small Rectangular Halter Plate - 3½" x ½" which mounts on door. 2" x 8".