02 Whole.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As Far As Her Eyes Are Good

As far as her eyes are good Essays on the political duality of domestic embroidery Ludovica Colacino To Angelina Scarpino, Teresina D’amico, and Concetta Mastroianni. 4 Introduction At the entrance to my home, on the left-hand side, an old, heavy, wooden chest of drawers acts as a small family altar. Amongst the framed photographs and décor atop it, a traditional Neapolitan miniature figure of a hunched old man guards the door to protect the house from the evil eye. It’s dressed in traditional Neapolitan clothes and is adorned with symbols to keep the bad luck away. A red horn, the number thirteen, and a horseshoe dangle from its belt and cloves of garlic sit on the brim of his hat. My mother bought it whilst on holiday in Naples; I remember in the shop I asked her why she was buying it, as we are from Calabria — it somehow felt like we were subscribing to a different set of beliefs. She explained that those charms of good luck are the same across the regions, especially in the South of Italy.1 Back in my family’s household, far from Naples and the South at large, in Piedmont, a region at the Northern end of the Country, the Neapolitan guardian on the comò 2 shows the amulets, peremptory shielding the family and the house — but, most immediately, secretly guarding the embroidered linens and cottons right beneath it, resting, folded, within the furnishing. My mother’s corredo 3 for the dining room makes the heart of the chest of drawers. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Subjugation IV

Subjugation 4 Tribulation by Fel (aka James Galloway) ToC 1 To: Title ToC 2 Chapter 1 Koira, 18 Toraa, 4401, Orthodox Calendar Wednesday, 28 January 2014, Terran Standard Calendar Koira, 18 Toraa, year 1327 of the 97th Generation, Karinne Historical Reference Calendar Foxwood East, Karsa, Karis Amber was starting to make a nuisance of herself. There was just something intrinsically, fundamentally wrong about an insufferably cute animal that was smart enough to know that it was insufferably cute, and therefore exploited that insufferable cuteness with almost ruthless impunity. In the 18 days since she’d arrived in their house, she’d quickly learned that she could do virtually anything and get away with it, because she was, quite literally, too cute to punish. Fortunately, thus far she had yet to attempt anything truly criminal, but that didn’t mean that she didn’t abuse her cuteness. One of the ways she was abusing it was just what she was doing now, licking his ear when he was trying to sleep. Her tiny little tongue was surprisingly hot, and it startled him awake. “Amber!” he grunted incoherently. “I’m trying to sleep!” She gave one of her little squeaking yips, not quite a bark but somewhat similar to it, and jumped up onto his shoulder. She didn’t even weigh three pounds, she was so small, but her little claws were like needles as they kneaded into his shoulder. He groaned in frustration and swatted lightly in her general direction, but the little bundle of fur was not impressed by his attempts to shoo her away. -

Tracie Thoms Talented Singer-Actress Speaks Wandering out for Alzheimer’S Research Real-World Advice for Keeping Your Loved One from Straying

Memorypreserving your Summer 2010 The Magazine of Health and Hope Tracie Thoms Talented singer-actress speaks Wandering out for Alzheimer’s research Real-world advice for keeping your loved one from straying The Latest News on Alzheimer’s Disease and Brain Health ALZTalk.org, is a free and easy way to make new friends and stay connected with those in the Alzheimer’s community. Join today to post messages and share pictures and favorite links. ALZTalk.org gives users a voice and allows them to share tips and stories about coping with loved ones with Alzheimer's. It also offers the ability to ask our experts questions no matter how large or small. Chat Online Share Your Photos & Set Up Your Events Profile in 1 Easy Step Get Answers to Your Questions Visit ALZTalk.org for the most comprehensive Alzheimer’s community resource online. Brought to you by the Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Research Foundation and ALZinfo.org *Content has been altered to protect user identity and data. Features West 46th Street & 12th Avenue New York, NY 10036 1-800-ALZ-INFO Photo: Michael Yarish/Warner Bros. www.ALZinfo.org Kent L. Karosen, Publisher Betsey Odell, Editor in Chief Alan White, Managing Editor William J. Netzer, Ph.D., Science Editor Jerry Louis, Graphic Designer Toby Bilanow, Bernard A. Krooks, 18 Contributing Writers 8 A Day Out Being a caregiver for an Alzheimer’s patient does not mean you have to stay home all the time. 10 Wandering Away Wandering is a major problem for Alzheimer’s patients, but there are steps you can take to help make sure it doesn’t happen to your loved one. -

Black Queer Southern Revelations Mitchell Joseph Sewell University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Senior Theses Honors College Spring 5-5-2016 Standpoint: Black Queer Southern Revelations MItchell Joseph Sewell University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Sewell, MItchell Joseph, "Standpoint: Black Queer Southern Revelations" (2016). Senior Theses. 87. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/87 This Thesis is brought to you by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-5-2016 Standpoint: Black Queer Southern Revelations MItchell Joseph Sewell Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents THESIS .............................................................................................................................. 4 WHY WAS THIS NECESSARY? .......................................................................................... 4 THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS: PERSONAL -

Himmelstein, Paul Himmelstein, Paul

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Oral Histories Bronx African American History Project 11-11-2005 Himmelstein, Paul Himmelstein, Paul. Bronx African American History Project Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_oralhist Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Himmelstein, Paul. November 11, 2005. Interview with the Bronx African American History Project. BAAHP Digital Archive at Fordham University. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Bronx African American History Project at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interviewee: Paul Himmelstein Interviewer: Dr. Mark Naison and Dr. Brian Purnell Date: November 11, 2005 Mark Naison (MN): Paul Himmelstein a great Doo-Wop singer from the Morrisania neighborhood and it’s November 11th and we are at Fordham University. MN: Paul Tell us a little about your family and how - - were you born in the Bronx? Paul Himmelstein (PH): Yes. I was born at Prospect and Jennings Street I'm one of fourteen children, I'm number eleven as I previously said and it was a family orientated neighborhood. I mean, there were a few big families and we were one of them. Like I said, we were fourteen but the Chandlers, there was a family called the Chandlers, they had seventeen and the Browns had ten. The Elis - - they had nine so I'm just giving names of the top of my head, which of course Eli - one of them sang with me the base, he was he bass and then Bobby Higgs he had ten in his family. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Imani, Who Are Already Munching Away

This book is dedicated to all the young people who must meld and merge, synthesize and harmonize, to create family fusion. CHAPTER 1 PLUNK. Plink. Ripple. Rumble. Tinkle. Twinkle. Boomble. I know that’s not an actual word, but it’s a real sound. I can create any musical combination of sounds on my piano. That’s my superpower. I sit, hands perched with thirsty fingers, as I get ready to play. I work hard at it, always trying to find the right melodies and harmonies. The upstairs-downstairs scales that rise and fall. The three- and four-finger chords that stomp. The fingernail-delicate tiptoeing up and down the keyboard, each touch a new sound. White keys. Black keys. One at a time. Chords all together. Two keys make a different sound than three played together. Four or five mashed at the same time is even better. I can do nine keys, even ten, to make a chord, but to be honest, that sounds weird. Each combination at the piano is different. Bass. Treble. Major tones. Minor wails. Bass like a celebration. Treble like tears. Five-four-three-two-one. One-two-three-four-five. Up. Up. Up. Down. Down. Down. Harmony. Melody. Chords. Scales. The black keys play sad sounds, like somebody crying. The white keys sometimes laugh. Using only my fingers, I can make the black and white keys dance together and do whatever I want. When I play the piano, I rock! It would be nice if the rest of my life came together like some kind of a magical musical symphony. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title DiscID Title DiscID 10 Years 2 Pac & Eric Will Wasteland SC8966-13 Do For Love MM6299-09 10,000 Maniacs 2 Pac & Notorious Big Because The Night SC8113-05 Runnin' SC8858-11 Candy Everybody Wants DK082-04 2 Unlimited Like The Weather MM6066-07 No Limits SF006-05 More Than This SC8390-06 20 Fingers These Are The Days SC8466-14 Short Dick Man SC8746-14 Trouble Me SC8439-03 3 am 100 Proof Aged In Soul Busted MRH10-07 Somebody's Been Sleeping SC8333-09 3 Colours Red 10Cc Beautiful Day SF130-13 Donna SF090-15 3 Days Grace Dreadlock Holiday SF023-12 Home SIN0001-04 I'm Mandy SF079-03 Just Like You SIN0012-08 I'm Not In Love SC8417-13 3 Doors Down Rubber Bullets SF071-01 Away From The Sun SC8865-07 Things We Do For Love SFMW832-11 Be Like That MM6345-09 Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814-01 Behind Those Eyes SC8924-02 We Do For Love SC8456-15 Citizen Soldier CB30069-14 112 Duck & Run SC3244-03 Come See Me SC8357-10 Here By Me SD4510-02 Cupid SC3015-05 Here Without You SC8905-09 Dance With Me SC8726-09 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) CB30070-01 It's Over Now SC8672-15 Kryptonite SC8765-03 Only You SC8295-04 Landing In London CB30056-13 Peaches & Cream SC3258-02 Let Me Be Myself CB30083-01 Right Here For You PHU0403-04 Let Me Go SC2496-04 U Already Know PHM0505U-07 Live For Today SC3450-06 112 & Ludacris Loser SC8622-03 Hot & Wet PHU0401-02 Road I'm On SC8817-10 12 Gauge Train CB30075-01 Dunkie Butt SC8892-04 When I'm Gone SC8852-11 12 Stones 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Crash TU200-04 Landing In London CB30056-13 Far Away THR0411-16 3 Of A Kind We Are One PHMP1008-08 Baby Cakes EZH038-01 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

I'll Make a Man out of You 000 Maniacs 10 More Than This 10,000

# -- -- 20 Fingers I'll Make A Man Out Of You Short #### Man 000 Maniacs 10 20th Century Boy More Than This T. Rex 10,000 Maniacs 21St Century Girls Because The Night 21St Century Girls Like The Weather More Than This 2 Chainz feat.Chris Brown These Are The Days Countdown Trouble Me Countdown (MPX) 100% Cowboy 2 Chainz ftg. Drake & Lil Wayne Meadows, Jason I Do It 101 Dalmations (Disney) 2 Chainz & Wiz Khalifa Cruella De Vil We Own It (Fast & Furious) 10cc 2 Evisa Donna Oh La La La Dreadlock Holiday I'm Mandy 2 Live Crew I'm Not In Love Rubber Bullets Do Wah Diddy Diddy The Things We Do For Love Me So Horny Things We Do For Love We Want Some P###Y Things We Do For Love, The Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pac California Love 112 California Love (Original ... Dance With Me Changes Dance With Me (Radio Version) Changes Peaches And Cream How Do You Want It Peaches And Cream (Radio ... Until The End Of Time (Radio ... Peaches & Cream Right Here For You 2 Pac & Eminem U Already Know One Day At A Time 112 & Ludacris 2 Pac & Eric Will Hot & Wet Do For Love 12 Gauge 2 Pac Featuring Dr. Dre Dunkie Butt California Love 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2 Pistols & Ray J. 1, 2, 3 Red Light You Know Me Simon Says You Know Me (Wvocal) 1975 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay Dizm Sincerity Is Scary She Got It TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME She Got It (Wvocal) 1975, The 2 Unlimited Chocolate No Limits 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 1 # 30 Seconds To Mars When Your Young .. -

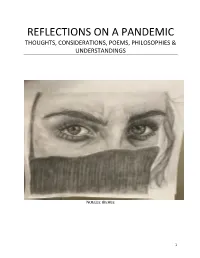

Reflections on a Pandemic Thoughts, Considerations, Poems, Philosophies & Understandings

REFLECTIONS ON A PANDEMIC THOUGHTS, CONSIDERATIONS, POEMS, PHILOSOPHIES & UNDERSTANDINGS NOELLE BIEHLE intin awingI 1 Open with INTRODUCTION The coronavirus pandemic has changed us all. No one could have predicted the ways in which we would become different, in our outlooks, our physical living conditions, and in the ways we connect (or don’t) with each other. Towards the end of April, I sent our seventh graders a collection of questions, created by the organization Facing History and Ourselves. The same organization created an activity called “Toolbox for Care,” in which students we asked to put together a collection of items for both self-care and care for others. What follows is their thoughts and ideas during the time of quarantine. Thank you, Noelle, for your breathtaking art! Frieda Katz At this time where there is a worldwide pandemic spreading fear and anguish across the globe, pain is unavoidable. It can be the mental pain of losing a family member, friends or physical pain where the virus has gotten to you. The pain can also be subtle, such as missing friends who are trapped inside their homes like 2 yourself. This pain is a reflection of how human interaction is vital for people to survive through life. Distress can cause depression or stressing about education, work, sports or health. The corona virus has brought more stress around the world than anything else my generation has seen. The serenity of isolation, Alone on a hill of daisies, As bright as the sun blinding my eyes, Forcing them to close, and eventually relax under the heat, My feet brushing against the grass, Filled with warmth but at the same time, Swaying to the rhythm of the autumn’s breeze, If only this was real, Such peace, No wars or diseases or death, Coming from behind, And grabbing your loved ones from your shaking arms, Not looking back once too see the pain it's brought, To a broken world, Never perfect, Never will be perfect.