Gouverneur Hospital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy the Spring Course

New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy The Spring Course: Best of DDW 2021 Saturday, June 5, 2021 8:00 am – 3:15 pm Virtual Event The Spring Course: Best of DDW 2021 is jointly provided by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center and the New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Page 1 of 10 Course Description The Spring Course is devoted to a review of the most compelling topics discussed during Digestive Disease Week® 2021. Faculty will present critically important information on new drugs, the etiology and pathophysiology of disease states, the epidemiology of diseases, the medical, surgical and endoscopic treatment of disease, and the social impact of disease states pertaining to gastroenterology, endoscopy, and liver disease. The program includes a video forum of new endoscopic techniques as well as a summary of the major topics presented at the most important academic forum in gastroenterology, making for an invaluable educational experience for those who were unable to attend Digestive Disease Week® and an excellent summary review for all others. Learning Objectives • Discuss the spectrum of gastrointestinal diseases such as motility disorders and colorectal cancer and outline the enhancement and effectiveness of related treatment options such as the use of artificial intelligence in the detection and resection of polyps during colonoscopy • Evaluate advances in the methods of assessing disease status in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and discuss the application of these techniques -

Rheumatology

NYU Langone Medical Center 550 First Avenue, New York, NY 10016 nyulmc.org RHEUMATOLOGY 2014 YEAR IN REVIEW CONTENTS 1 Letter from the Chairs 2 Facts & Figures 1 Message from the Director 4 New & Noteworthy 2 Facts & Figures 6 Section 4 New & Noteworthy 42 Research 10 Clinical Care and Research 44 Education 11 Lupus and Neonatal Lupus 13 Behçet’s Syndrome 48 Publications 14 Rheumatology and Osteoporosis 5164 LoPsoriaticcations Arthritis 18 Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis 55 Leadership 20 Education & Training 56 NYU Langone Medical Center Facts & Figures 24 Professional Activities 57 NYU Langone Medical Center Leadership Design: Ideas On Purpose, www.ideasonpurpose.com 27 Leadership, Locations Produced by: Office of Communications and Marketing, NYU Langone Medical Center NYU LANGONE MEDICAL CENTER / RHEUMATOLOGY / 2014 PAGE 1 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Colleagues and Friends, The tripartite mission of our division is clear: Deliver comprehensive state-of-the-art clinical care, translate and integrate medicine and science, and increase the knowledge base of our trainees. I’m proud to report that in 2014, with the dedication of all faculty members, we have made significant strides in all three areas, as evidenced in the following pages. Under the guidance of our previous division director, Steven B. Abramson, MD, now chair of the Department of Medicine, the Judith and Stewart Colton Center for Autoimmunity was established. The center aims to advance discoveries about the microbiome and its relationship to autoimmune disease, and to leverage this new knowledge to develop strategies for prevention and JILL P. BUYON, MD treatment. Our vision of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary Psoriatic Arthritis Center dedicated to the bench-to-bedside integration of dermatology and Director, Division of Rheumatology, rheumatology has now been realized, and a strong laboratory research base will Department of Medicine stand behind this center to further our understanding of psoriatic arthritis and NYU Langone Medical Center develop novel therapies. -

Villagecaremax Medicare Health Advantage (HMO SNP) 2019 Provider & Pharmacy Directory

H2168_MBR19-55_C VillageCareMAX Medicare Health Advantage (HMO SNP) 2019 Provider & Pharmacy Directory This Provider & Pharmacy Directory was updated on 6/6/2019. For more recent information or other questions, please contact VillageCareMAX Medicare Health Advantage (HMO SNP) Member Services at 1-800-469-6292 or, for TTY users, 711, 8:00 am to 8:00 pm, 7 days a week, or visit www.villagecaremax.org. Changes to our provider and pharmacy network may occur during the benefit year. An updated Provider & Pharmacy Directory is located on our website at www.villagecaremax.org. You may also call Member Services for updated provider. i VillageCareMAX Medicare Health Advantage (HMO SNP) 2019 Provider Directory This directory is current as of June 06, 2019. This directory provides a list of VillageCareMAX Medicare Health Advantage’s (HMO SNP) current network providers. This directory is for New York (Manhattan) county. To access VillageCareMAX Medicare Health Advantage’s online provider directory, you can visit www.villagecaremax.org to view the complete directory or providers in another county. For any questions about the information contained in this directory, to request a hardcopy, or to get help finding a provider in another county, please call our Member Service Department at 1-800- 469-6292, 8:00 am to 8:00 pm, 7 days a week. TTY/TDD users should call 711. ATTENTION: If you speak English, language assistance services, free of charge, are available to you. Call 1-800-469-6292 (TTY: 711). ATENCIÓN: si habla español, tiene a su disposición servicios gratuitos de asistencia lingüística. Llame al 1-800-469-6292 (TTY: 711). -

1 FULL BOARD MINUTES DATE: July 19, 2001

FULL BOARD MINUTES DATE: July 19, 2001 TIME: 7:00 P.M. PLACE: St. Vincent’s Hospital, 170 W. 12th Street Cronin Auditorium, 10th Floor BOARD MEMBERS PRESENT: Ann Arlen, Steve Ashkinazy, Tobi Bergman, Glenn Bristow, Helene Burgess, Charle-John Cafiero, Anthony Dapolito, Doris Diether, Carol Feinman, Harriet Fields, Alan Jay Gerson, Elizabeth Gilmore, Edward Gold, Arnold L. Goren, Jo Hamilton, Anne Hearn, Brad Hoylman, Honi Klein, Lisa LaFrieda, Aubrey Lees, Chair, Community Board #2, Manhattan (CB#2, Man.) MacPherson, Rosemary McGrath, Doris Nash, T. Marc Newell, David Reck, Carol Reichman, Robert Rinaolo, Ann Robinson, Debra Sandler, Rocio Sanz, Shirley Secunda, Ruth Sherlip, Melissa Sklarz, Verna Small, Sean Sweeney, Martin Tessler, Wilbur Weder, Jeanne Wilcke, Suzanne Williamson, Carol Yankay. BOARD MEMBERS EXCUSED: Rev. Keith Fennessy, Don Lee, Edward Ma, Arthur Z. Schwartz, John Short, James Smith, Betty Williams. BOARD MEMBERS ABSENT: Keith Crandell, Noam Dworman, Lora Tenenbaum BOARD STAFF PRESENT: Arthur Strickler, District Manager GUESTS: Daryl Cochrane, Congressman Jerrold Nadler’s office; Scott Melvin, Senator Tom Duane’s office; Meg Reed, Senator Martin Connor’s office; Yvonne Morrow, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver’s office; Debbie Roth, Assemblymember Deborah Glick's office; Boaz Green, Councilmember Kathryn Freed's office; Andree Tenemas, Councilmember Margarita Lopez’ office; Maura Keaney, Counclmember Christne Quinn’s office, Blane Roberts, Man. Borough President’s office; Joan Engel, Barbara Hodes, Mary K. Doris, Boaz -

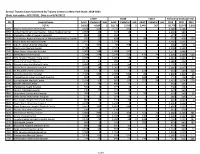

Annual Trauma Cases Submitted by Trauma Centers in New York State

Annual Trauma Cases Submitted by Trauma Centers in New York State: 2018-2021 (Date last update: 8/17/2021, Data as of 8/3/2021) Y2019 Y2020 Y2021 TOTALS by Discharge Year PFI Hospital Name Adult Pediatric Unk Adult Pediatric Unk Adult Pediatric Unk 2019 2020 2021 TOTAL 54,562 4,209 1 50,176 3,793 3 5,443 367 - 58,772 53,972 5,810 0001 Albany Medical Center Hospital 3,168 320 . 3,772 392 . 3,488 4,164 - 0058 United Health Services Hospital - Wilson Medical Center 1,067 23 . 934 13 . 1,090 947 - 0135 Champlain Valley Physicians Hospital 465 12 . 314 2 . 477 316 - 0180 Mid Hudson Regional Hospital of Westchester Medical Center 745 22 . 428 . 98 2 767 428 100 0181 Vassar Brothers Medical Center 1,141 15 . 1,029 2 . 1,156 1,031 - 0208 John R. Oishei Children's Hospital 64 335 . 68 258 2 4 399 326 6 0210 Erie County Medical Center 2,598 1 . 2,525 . 2,599 2,525 - 0245 Stony Brook University Hospital 2,003 168 . 1,686 162 . 2,171 1,848 - 0413 Strong Memorial Hospital 2,244 254 . 2,246 223 470 74 2,498 2,469 544 0511 NYU Langone Hospital-Long Island 1,288 77 . 1,305 56 26 8 1,365 1,361 34 0527 Mount Sinai South Nassau 1,171 17 . 989 4 . 1,188 993 - 0528 Nassau University Medical Center 1,384 34 . 1,187 25 . 1,418 1,212 - 0541 North Shore University Hospital 2,150 16 . 1,907 10 . -

Tenseniorstobowoutsaturday in Classic Battle With

E3fl Is' N«w Bandma.t.r dham's nd Plans to *» d Al McNqmora Giv« Viawt ns On The New Monthly's Top* •« City— N«w Look- Pag* 3 FORDHAM COLLEGE, NEW~YORK, NOVEMBER 21, 1951 Defense: Fordham's Unit Stars in Drill TenSeniorstoBowOutSaturday As dozens of sirens in the New York area sprung into action and sound- • Bir warning of the practice air raid Wednesday evening Nov. 14, Ford- In Classic Battle with NYU University's Civil Defense Mobile First Aid Unit was stationed at post at Fordham Hospital, waiting to be called into action. By MM JACOBY In the Fordham unit, there were 184 personnel, consisting entirely of In the twenty-ninth renewal of the Fordham-NYU grid rivalry, ten •dents and faculty members of the® TELECAST FROM CHURCH Maroon Seniors will ring down the curtain on their college football armacy School. The unit was or The Fordham University Church careers this Saturday at Randall's Island. Taking the field for the last nized and under the direction o: will be the scene of a series of time will be such defensive stalwarts as end and Captain Chris Campbell, Leonard J. Piccoli, Professor o StudentsConfer nation-wide telecasts over the tackle Art Hickey, end Tom Bourke, halfback Bill Sullivan, end Dick lic Health of the Fordham Col- National Broadcasting Company fMotta, and guard Bill Snyder. The e of Pharmacy. The Medical Di during the month of'December. offensive stars who will bid adieu tor of the aid station is Dr. Josep! With Faculty The NBC television series, include Ed Kozdeba, extra-point s and the Chaplain is Rev. -

Metroplus MLTC Provider Directory Table of Contents

MetroPlus MLTC Provider Directory Table of Contents Introduction ..........................................................................................................................3 Adult Day Health Care .......................................................................................................5 AIDS Adult Day Health Care Centers ..............................................................................7 Audiology/Hearing ..............................................................................................................8 Certified Home Health Care ..............................................................................................9 Consumer Directed Personal Care Services ...............................................................11 Durable Medical Equipment (DME) ................................................................................12 Facility Based Occupational Therapy ............................................................................25 Facility Based Physical Therapy .....................................................................................26 Facility Based Speech Therapy ......................................................................................27 Home Delivered Meals / Congregate Meals .................................................................28 Non-Emergent Transportation ........................................................................................30 Orthotics and Prosthetics.................................................................................................34 -

HIV Testing Locations

HIV Testing Locations Site ID Agency ID Site Name 810 Office of the Manhattan Borough President Office of the Manhattan Borough President 53 Clinic - Lenox Avenue Clinic - Lenox Avenue 90 HHC Gouverneur Health HHC Gouverneur Health 167 NYC DOHMH TB Control Morrisania Chest Center Clinic 822 Bronx - Lebanon Hospital Center BronxCare Fulton Family Medicine 524 Community Health Action of Staten Island Community Health Action of Staten Island- (CHASI) Main Office 119 United Family Church-Iglesia De La Familia La Familia Unida Unida 605 Metroplus Healthplan Metroplus Healthplan 442 Transdiaspora Network Transdiaspora Network 542 New York Presbyterian Hospital NYP - Westchester Division 746 Greater Brooklyn Health Coalition Greater Brooklyn Health Coalition 495 Urban Justice Center (SWOP) Urban Justice Center 641 New York State Health Department New York State Health Department 452 Young Women of Color HIV/AIDS Coalition Young Women of Color HIV/AIDS Coalition 341 CAUSE-NY Jewish Community Relations CAUSE-NY Jewish Community Relations Council of New York Council of New York Page 1 of 533 09/30/2021 HIV Testing Locations Hours Monday Hours Tuesday 11:00 AM - 7:00 PM 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM 8:00 AM - 8:00 PM 8:00 AM - 8:00 PM CLOSED CLOSED 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM Page 2 of 533 09/30/2021 HIV Testing Locations Hours Wednesday Hours Thursday 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM 8:30 AM - 5:00 PM 8:00 AM - 8:00 PM 8:30 AM - 5:00 PM 8:30 AM - 5:00 PM 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM Page 3 of 533 09/30/2021 HIV Testing Locations Hours Friday -

August 9, 2021 RELIEF RESOURCES and SUPPORTIVE

September 24, 2021 RELIEF RESOURCES AND SUPPORTIVE INFORMATION1 • Health & Wellness • Housing • Workplace Support • Human Rights • Education • Bilingual and Culturally Competent Material • Beware of Scams • Volunteering • Utilities • Legal Assistance • City and State Services • Burial • Transportation • New York Forward/Reopening Guidance • Events HEALTH & WELLNESS • Financial Assistance and Coaching o COVID-19 Recovery Center : The City Comptroller has launched an online, multilingual, comprehensive guide to help New Yorkers navigate the many federal, state and city relief programs that you may qualify for. Whether you’re a tenant, homeowner, parent, small business owner, or excluded worker, this online guide offers information about a range of services and financial support. o New York City will be extending free tax assistance to help families claim their new federal child tax credit. As an investment in the long-term recovery from the pandemic, the federal American Rescue Plan made changes to the Child Tax Credit so families get half of the fully refundable credit—worth up to $3,600 per child—as monthly payments in 2021 and the other half as a part of their refund in 1 Compiled from multiple public sources 2022. Most families will automatically receive the advance payments, but 250,000+ New York City families with more than 400,000 children need to sign up with the IRS to receive the Credit. The Advance Child Tax Credits payments began on July 15, 2021 and most New Yorkers will receive their payments automatically. However, New Yorkers who have not submitted information to the IRS need to either file their taxes or enter their information with the IRS’ Child Tax Credit Non-Filer Sign-Up Tool For more information about the Advance Child Tax Credit including access to Multilingual flyer and poster—and NYC Free Tax Prep, visit nyc.gov/TaxPrep or call 311. -

Division of Community and Population Health Report

Division of Community and Population Health Report Table of Contents Expanding Our Reach to Help More Neighbors 1 Community and Population Health Leadership 2 About NewYork-Presbyterian 3 Division of Community and Population Health: Our Mission 4 Clinical Services: Ambulatory Care Network 6 Ambulatory Care Network Nursing 11 Telehealth 13 Community Health Programs 14 ANCHOR (Addressing the Needs of the Community Through Holistic, Organizational Relationships) 15 Behavioral Health Clinical Services (Outpatient) 16 Building Bridges, Knowledge and Health Coalition 18 Center for Community Health and Education 19 CCHE: Family Planning Program and Young Men’s Clinic 20 CCHE: School-Based Health Center Program 21 CCHE: Uptown Hub 22 Center for Community Health Navigation 24 Centering Pregnancy Program and The Carnegie Hall Lullaby Project 26 Collaborator Network Workforce Development and Training 27 Choosing Healthy & Active Lifestyles for Kids™ (CHALK) 28 Compass 30 Community-Based Sexual Health 31 Cultural Competency and Health Literacy Workgroup 35 Health & Housing 36 Health for Life 37 Health Home 38 Healthy City Kids 39 Lang Youth Medical Program 40 Manhattan Cancer Services Program 41 NewYork-Presbyterian Performing Provider System Impact Grants 42 Outreach Program 43 Reach Out and Read Program 44 The Family PEACE (Preventing Early Adverse Childhood Experiences) Trauma Treatment Center 45 Turn 2 Us (T2U) 46 Waiting Room As a Literacy & Learning Environment (WALLE) 47 Women, Infants, and Children Program (WIC) 48 Workforce Development and -

HAVAA Invitation

RD AWA XILIAN AN EMENT L AU D VOLUNTEER ACHIEV ITA SP HO D AR AW T EN EM V IE H C A R E E T N U The United Hospital Fund is dedicated to creating the health care system all of us want for ourselves, our families, and our neighbors. Please consider honoring one of today’s extraordinary volunteers or auxilians, and supporting the work of the Fund, by becoming a Patron or Sponsor. This unique awards program brings public attention to the invaluable contributions of our honorees, and the other 50,000 committed volunteers in our city, who make such an important difference to patients and their families and extend the ability of New York’s hospitals to provide the best care possible. Patrons and Sponsors will be recognized in the event’s Program and all gifts will be gratefully acknowledged. Please use the enclosed reply card to indicate your level of support. Please join us for tea at the Waldorf as the United Hospital Fund honors the 2009 recipients of the # HOSPITAL AUXILIAN and VOLUNTEER ACHIEVE#MENT AWARD Friday, March 6, 2009 1:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m The Grand Ballroom of The Waldorf-Astoria Park Avenue at 50th Street, New York City Special Guest Sade Baderinwa Co-anchor,WABC-TV Eyewitness News at 5:00 RSVP by February 10, 2009 on the enclosed card Generously underwritten by TD Bank United Hospital Fund The United Hospital Fund is a health services research and J. Barclay Collins II philanthropic organization whose Chairman mission is to shape positive change James R. -

Rethinking Private-Public Partnership in the Health Care Sector: The

This is a preprint of an accepted article scheduled to appear in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 93, no. 4 (Winter 2019). It has been copyedited but not paginated. Further edits are possible. Please check back for final article publication details. Rethinking Private-Public Partnership in the Health Care Sector: The Case of Municipal Hospital Affiliation MERLIN CHOWKWANYUN SUMMARY: By the late 1950s, New York City’s public hospital system—more extensive than any in the nation—was falling apart, with dilapidated buildings and personnel shortages. In response, Mayor Robert Wagner authorized an affiliation plan whereby the city paid private academic medical centers to oversee training programs, administrative tasks, and resource procurement. Affiliation sparked vigorous protest from critics, who saw it as both an incursion on the autonomy of community-oriented public hospitals and the steamrolling of private interests over public ones. In the wake of the New York City fiscal crisis of 1975, however, the viability of a purely public hospital system withered, given the new economic climate facing the city. In its place was a new institutional form: affiliation and the public-private provision of public health care. KEYWORDS: urban health, New York City, protest, hospitals, health services, health care, public health, public policy, private-public partnerships, academic medical centers 1 This is a preprint of an accepted article scheduled to appear in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 93, no. 4 (Winter 2019). It has been copyedited but not paginated. Further edits are possible. Please check back for final article publication details.