Thesis Hum 2012 Mabandla N.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Direction on Measures to Address, Prevent and Combat the Spread of COVID-19 in the Air Services for Adjusted Alert Level 3

Laws.Africa Legislation Commons South Africa Disaster Management Act, 2002 Direction on Measures to Address, Prevent and Combat the Spread of COVID-19 in the Air Services for Adjusted Alert Level 3 Legislation as at 2021-01-29. FRBR URI: /akn/za/act/gn/2021/63/eng@2021-01-29 PDF created on 2021-10-02 at 16:36. There may have been updates since this file was created. Check for updates About this collection The legislation in this collection has been reproduced as it was originally printed in the Government Gazette, with improved formatting and with minor typographical errors corrected. All amendments have been applied directly to the text and annotated. A scan of the original gazette of each piece of legislation (including amendments) is available for reference. This is a free download from the Laws.Africa Legislation Commons, a collection of African legislation that is digitised by Laws.Africa and made available for free. www.laws.africa [email protected] There is no copyright on the legislative content of this document. This PDF copy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (CC BY 4.0). Share widely and freely. Table of Contents South Africa Table of Contents Direction on Measures to Address, Prevent and Combat the Spread of COVID-19 in the Air Services for Adjusted Alert Level 3 3 Government Notice 63 of 2021 3 1. Definitions 3 2. Authority of directions 4 3. Purpose of directions 4 4. Application of directions 4 5. Provision of access to hygiene and disinfection control at airports designated as Ports of Entry 4 6. -

Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University: Training Doctors from and for Rural South African Communities

Original Scientific Articles Medical Education Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University: Training Doctors from and for Rural South African Communities Jehu E. Iputo, MBChB, PhD ABSTRACT Outcomes To date, 745 doctors (72% black Africans) have graduated Introduction The South African health system has disturbing in- from the program, and 511 students (83% black Africans) are currently equalities, namely few black doctors, a wide divide between urban enrolled. After the PBL/CBE curriculum was adopted, the attrition rate and rural sectors, and also between private and public services. Most for black students dropped from 23% to <10%. The progression rate medical training programs in the country consider only applicants with rose from 67% to >80%, and the proportion of students graduating higher-grade preparation in mathematics and physical science, while within the minimum period rose from 55% to >70%. Many graduates most secondary schools in black communities have limited capacity are still completing internships or post-graduate training, but prelimi- to teach these subjects and offer them at standard grade level. The nary research shows that 36% percent of graduates practice in small Faculty of Health Sciences at Walter Sisulu University (WSU) was towns and rural settings. Further research is underway to evaluate established in 1985 to help address these inequities and to produce the impact of their training on health services in rural Eastern Cape physicians capable of providing quality health care in rural South Af- Province and elsewhere in South Africa. rican communities. Conclusions The WSU program increased access to medical edu- Intervention Access to the physician training program was broad- cation for black students who lacked opportunities to take advanced ened by admitting students who obtained at least Grade C (60%) in math and science courses prior to enrolling in medical school. -

International Air Services (COVID-19 Restrictions on the Movement of Air Travel) Directions, 2020

Laws.Africa Legislation Commons South Africa Disaster Management Act, 2002 International Air Services (COVID-19 Restrictions on the movement of air travel) Directions, 2020 Legislation as at 2020-12-03. FRBR URI: /akn/za/act/gn/2020/415/eng@2020-12-03 PDF created on 2021-09-26 at 02:36. There may have been updates since this file was created. Check for updates About this collection The legislation in this collection has been reproduced as it was originally printed in the Government Gazette, with improved formatting and with minor typographical errors corrected. All amendments have been applied directly to the text and annotated. A scan of the original gazette of each piece of legislation (including amendments) is available for reference. This is a free download from the Laws.Africa Legislation Commons, a collection of African legislation that is digitised by Laws.Africa and made available for free. www.laws.africa [email protected] There is no copyright on the legislative content of this document. This PDF copy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (CC BY 4.0). Share widely and freely. Table of Contents South Africa Table of Contents International Air Services (COVID-19 Restrictions on the movement of air travel) Directions, 2020 3 Government Notice 415 of 2020 3 1. Definitions 3 2. Authority 4 3. Purpose of directions 4 4. Application of the directions 4 5. International flights and domestic flights 4 5A. Airport and airlines 7 5B. General aviation 7 5C. *** 8 5D. Compliance with the measures for the prevention of the spread of COVID-19 8 6. -

Download Brochure

PARADISE FOUND PARADISE FOUND WELCOME TO UMNGAZI HOTEL & SPA Umngazi Hotel & Spa is nestled alongside the Umngazi River, 20kms south of Port St Johns, on the Wild Coast, Eastern Cape. The area is untouched and naturally beautiful with plenty to keep you as busy or as lazy as you prefer to be. The resort oers all who visit, tasteful and spacious thatched rooms, delicious, fresh and wholesome food and a wide array of activities. A visit to this special part of the country will give you the chance to pause from life, reconnect and restore, and when you leave you will leave with a happy heart and a peaceful soul. ULTIMATE EXPERIENCE ULTIMATE EXPERIENCE YOUR TIME AND EXPERIENCE AT UMNGAZI WILL STAY IN YOUR HEART FOREVER The peace, beauty, stillness and tranquility you experience whilst staying at the hotel will keep you wanting to come back time and time again. The warmth and smiling faces of the sta, the amazing home away from home feeling, the understated comfort of the rooms and furnishings around the hotel, the abundance of food and award-winning wine list will rearm why Umngazi is such a well sought after resort in South Africa. Everyone’s experience at Umngazi is dierent – whether you are a young family looking for time out from the busy routine of home life; whether you are wanting to reconnect with loved ones again; a group of friends looking to create memories together; celebrating a special occasion or anniversary; the list is endless. COMPLETE COMFORT COMPLETE COMFORT UMNGAZI CELEBRATES COMFORT Comfort in accommodation. -

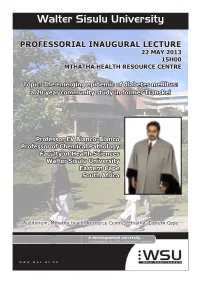

Walter Sisulu University

Walter Sisulu University PROFESSORIAL INAUGURAL LECTURE 22 MAY 2013 15H00 MTHATHA HEALTH RESOURCE CENTRE Topic: The emerging epidemic of diabetes mellitus: a 20 year community study in former Transkei Professor EV Blanco-Blanco Professor of Chemical Pathology Faculty of Health Sciences Walter Sisulu University Eastern Cape South Africa Auditorium, Mthatha Health Resource Centre, Mthatha, Eastern Cape www.wsu.ac.za WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY (WSU) DEPARTMENT OF CHEMICAL PATHOLOGY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES TOPIC “THE EMERGING EPIDEMIC OF DIABETES MELLITUS: A 20-YEAR COMMUNITY STUDY IN THE FORMER TRANSKEI” BY ERNESTO V. BLANCO-BLANCO PROFESSOR OF CHEMICAL PATHOLOGY DATE: 22 MAY 2013 VENUE: UMTATA HEALTH RESOURCE CENTRE 3 4 INTRODUCTION AND TOPIC MOTIVATION DIABETES MELLITUS Definition Historical background CLASSIFICATION OF DIABETES MELLITUS DIAGNOSIS OF DIABETES MELLITUS RISK FACTORS AND PREDISPOSING CONDITIONS FOR DIABETES COMPLICATIONS OF DIABETES MELLITUS THE GLOBAL PREVALENCE & GLOBAL BURDEN OF DIABETES THE AFRICAN BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS THE SOUTH AFRICAN BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS CONSEQUENCES OF THE BURDEN OF DIABETES IMPLICATIONS OF THE BURDEN OF DIABETES FOR HEALTH PLANNING DIABETES PREVENTION AS STRATEGY CONTROL OF THE CURRENT BURDEN OF DIABETES CONCLUSIONS REFERENCES 5 INTRODUCTION AND TOPIC MOTIVATION Chemical Pathology, Diabetes Mellitus and the Former Transkei I am a Chemical Pathologist by training. The term ‘pathology’ derives from the Greek words “pathos” meaning “disease” and “logos” meaning “a treatise”. Pathology is a major field of Medicine that deals with the essential nature of diseases, their processes and consequences. A medical doctor that specializes in pathology is known as ‘a pathologist’. Chemical Pathology is that branch of Pathology, which deals specially with the biochemical basis of diseases and the use of biochemical tests carried out at hospital laboratories on the blood and other body fluids to provide support to clinicians. -

The Power of Heritage to the People

How history Make the ARTS your BUSINESS becomes heritage Milestones in the national heritage programme The power of heritage to the people New poetry by Keorapetse Kgositsile, Interview with Sonwabile Mancotywa Barbara Schreiner and Frank Meintjies The Work of Art in a Changing Light: focus on Pitika Ntuli Exclusive book excerpt from Robert Sobukwe, in a class of his own ARTivist Magazine by Thami ka Plaatjie Issue 1 Vol. 1 2013 ISSN 2307-6577 01 heritage edition 9 772307 657003 Vusithemba Ndima He lectured at UNISA and joined DACST in 1997. He soon rose to Chief Director of Heritage. He was appointed DDG of Heritage and Archives in 2013 at DAC (Department of editorial Arts and Culture). Adv. Sonwabile Mancotywa He studied Law at the University of Transkei elcome to the Artivist. An artivist according to and was a student activist, became the Wikipedia is a portmanteau word combining youngest MEC in Arts and Culture. He was “art” and “activist”. appointed the first CEO of the National W Heritage Council. In It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop by M.K. Asante. Jr Asante writes that the artivist “merges commitment to freedom and Thami Ka Plaatjie justice with the pen, the lens, the brush, the voice, the body He is a political activist and leader, an and the imagination. The artivist knows that to make an academic, a historian and a writer. He is a observation is to have an obligation.” former history lecturer and registrar at Vista University. He was deputy chairperson of the SABC Board. He heads the Pan African In the South African context this also means that we cannot Foundation. -

2017/09/23 01 01Sd23092017 Saturday News 14

S at u r d a y 14 MINE PENSIONERS September 23, 2017 Sur name Name Member Office DOB Address Sur name Name Member Office DOB Address Nho C e ke n i M T H AT H A To claim from Teba offices: Ditanana Fa n t e s o M T H AT H A M ot h e Nondzaba M T H AT H A Live cases: 1: ID; 2: TEBA card (known as Makhuluskop); 3: Proof of M at h a b e l a Qhingeni M T H AT H A M g o b oz a William Q U E E N STO W N employment, like a leave certificate Tat a n a Bandana M T H AT H A N o m ya y i Ndazingani M T H AT H A Deceased Cases: 1: Beneficiary ID; 2: Death Certificate for deceased Alson G we l e MT FRERE Bangani Lungile M T H AT H A Mdungeni Manggumbo M T H AT H A 1 9 5 9 / 07 / 0 1 Qgakaza Bongeni M T H AT H A employee; 3: Proof of employment for deceased employee, like a leave Bat well Masikantsi M T H AT H A Jaf ta Tu s u LU S I K I S I K I 1945/12/10 JAMBENI A LOC cer tificate S i p h i wo Sakube M T H AT H A N kowa n a Mqumana M T H AT H A 1953/10/08 MZAMENI STORE (All names and addresses as supplied by Teba) Makhosandile Sithole LU S I K I S I K I Maraqa M s h i ye n i M T H AT H A 1960/02/09 NGCWANGUBA STORE N ko s i p h e n d u l e Nelani M T H AT H A Lilana N e we n e n e M T H AT H A 1955/03/10 MT PLEASANT STORE Sur name Name Member Office DOB Address Gosani D i n g i s wa yo M T H AT H A Qakumbana Light M T H AT H A 1945/01/10 QUANGUBA VILLAGE Gibson Xego M T H AT H A Putsetse M at o m e l a M T H AT H A N d we n d we Mbaqeni BUYISILE M T H AT H A 1950/02/03 BHUKWINI A/A Mbhodlana X h o l a yo M T H AT H A Zithulele Tot o B U T T E R W -

Lusikisiki Flagstaff and Port St Johns Sheriff Service Area

LLuussiikkiissiikkii FFllaaggssttaaffff aanndd PPoorrtt SStt JJoohhnnss SShheerriiffff SSeerrvviiccee AArreeaa DUNDEE Mandela IZILANGWE Gubhethuka SP Alfred SP OLYMPUS E'MATYENI Gxako Ncome A Siqhingeni Sithinteni Sirhoqobeni Ngwegweni SP Mruleni SP Izilangwe SP DELHI Gangala SP Mjaja SP Thembeni SP MURCHISON PORT SHEPSTONE ^ Gxako Ntlabeni SP Mpoza SP Mqhekezweni DUNDEE REVENHILL LOT SE BETHEL PORT NGWENGWENI Manzane SP Nhlanza SP LONG VALLEY PENRITH Gxaku Matyeni A SP Mkhandlweni SP Mmangweni SP HOT VALE HIGHLANDS Mbotsha SP ñ Mgungundlovu SP Ngwekazana SP Mvubini Mnqwane Xhama SP Siphethu Mahlubini SP NEW VALLEYS BRASFORT FLATS N2 SHEPSTONE Makolonini SP Matyeni B SP Ndzongiseni SP Mshisweni SP Godloza NEW ALVON PADDOCK ^ Nyandezulu SP LK MAKAULA-KWAB Nongidi Ndunu SP ALFREDIA OSLO Mampondomiseni SP SP Qungebe Nkantolo SP Gwala SP SP Mlozane ST HELENA B Ngcozana SP Natala SP SP Ezingoleni NU Nsangwini SP DLUDLU Ndakeni Ngwetsheni SP Qanqu Ntsizwa BETSHWANA Ntamonde SP SP Madadiyela SP Bonga SP Bhadalala SP SP ENKANTOLO Mbobeni SP UMuziwabantu NU Mbeni SP ZUMMAT R61 Umzimvubu NU Natala BETSHWANA ^ LKN2 Nsimbini SP ST Singqezi SIDOI Dumsi SP Mahlubini SP ROUNDABOUT D eMabheleni SP R405 Sihlahleni SP Mhlotsheni SP Mount Ayliff Mbongweni Mdikiso SP Nqwelombaso SP IZINGOLWENI Mbeni SP Chancele SP ST Ndakeni B SP INSIZWA NESTAU GAMALAKHE ^ ROTENBERG Mlenze A SIDOI MNCEBA Mcithwa !. Ndzimakwe SP R394 Amantshangase Mount Zion SP Isisele B SP Hlomendlini SP Qukanca Malongwe SP FIKENI-MAXE SP1 ST Shobashobane SP OLDENSTADT Hibiscus Rode ñ Nositha Nkandla Sibhozweni SP Sugarbush SP A/a G SP Nikwe SP KwaShoba MARAH Coast NU LION Uvongo Mgcantsi SP RODE Ndunge SP OLDENSTADT SP Qukanca SP Njijini SP Ntsongweni SP Mzinto Dutyini SP MAXESIBENI Lundzwana SP NTSHANGASE Nomlacu Dindini A SP Mtamvuna SP SP PLEYEL VALLEY Cabazi SP SP Cingweni Goso SP Emdozingana Sigodadeni SP Sikhepheni Sp MNCEBA DUTYENI Amantshangase Ludeke (Section BIZANA IMBEZANA UPLANDS !. -

Eastern Cape Algoa Park Port Elizabeth St Leonards Road Algoa Park Pharmacy (041) 4522036 6005411

CONTACT PRACTICE PROVINCE PHYSICAL SUBURB PHYSICAL TOWN PHYSICAL ADDRESS PHARMACY NAME NUMBER NUMBER EASTERN CAPE ALGOA PARK PORT ELIZABETH ST LEONARDS ROAD ALGOA PARK PHARMACY (041) 4522036 6005411 EASTERN CAPE ALIWAL NORTH ALIWAL NORTH 31 GREY STREET ALIWAL PHARMACY (051) 6333625 6037232 EASTERN CAPE ALIWAL NORTH ALIWAL NORTH CORNER OF ROBERTSON ROAD CLICKS PHARMACY ALIWAL (051) 6332449 670898 AND ALIWAL STREETS NORTH EASTERN CAPE ALIWAL NORTH ALIWAL NORTH 48 SOMERSET STREET DORANS PHARMACY (051) 6342434 6076920 EASTERN CAPE AMALINDA EAST LONDON MAIN ROAD MEDIRITE PHARMACY AMALINDA (043) 7412193 346292 EASTERN CAPE BEACON BAY EAST LONDON BONZA BAY ROAD BEACONHURST PHARMACY (043) 7482411 6003680 EASTERN CAPE BEACON BAY EAST LONDON BONZA BAY ROAD CLICKS PHARMACY BEACON BAY (043) 7485460 213462 EASTERN CAPE BEREA EAST LONDON 31 PEARCE STREET BEREA PHARMACY (043) 7211300 6003699 EASTERN CAPE BETHELSDORP PORT ELIZABETH STANFORD ROAD CLICKS PHARMACY CLEARY PARK (041) 4812300 192546 EASTERN CAPE BETHELSDORP PORT ELIZABETH CORNER STANFORD AND MEDIRITE PHARMACY (041) 4813121 245445 NORMAN MIDDELTON STREETS BETHELSDORP EASTERN CAPE BIZANA BIZANA 69 DAWN THOMSON DRIVE MBIZANA PHARMACY (039) 2510919 394696 EASTERN CAPE BLUEWATER BAY PORT ELIZABETH HILLCREST DRIVE KLINICARE BLUEWATER BAY (041) 4662662 95567 PHARMACY EASTERN CAPE BUTTERWORTH BUTTERWORTH 9B UMTATA STREET BUTTERWORTH PHARMACY (047) 4910976 6000428 EASTERN CAPE BUTTERWORTH BUTTERWORTH CORNER HIGH AND BELL KEI CHEMIST (047) 4910058 6069746 STREET GEMS SB NETWORK PHARMACY – EASTERN CAPE -

Where in the Eastern Cape Can I Purchase the Latest Diabetes Lifestyle Journal? Part 1

Where in the Eastern Cape can I purchase the latest Diabetes Lifestyle Journal? Part 1 City/Town Name of retail outlet Adelaide Winkle Adelaide Aliwal North Clicks Aliwal North Aliwal North Protea Kafee Bethelsdorp Clicks Kabega Park Blue Horizon Bay Spar Waterfront Cradock Spar Cradock East London Clicks Hemmingways East London Clicks Beacon Bay East London Clicks Vincent Park East London Clicks Amalinda East London Dis-Chem Pharm Hemmingsway East London Berea Pharmacy East London PicknPay Supermarket Southernwood East London Shoprite/Checkers Hemmingways Mall East London Shoprite/Checkers Nahoon East London Shoprite/Checkers Vincent East London Super Spar Spargs Fort Beaufort Spar Georgious Gonubie PicknPay Superm Gonubie Graaff-Reinet PicknPay Graaf Reinet Family Store Grahamstown Clicks Grahamstown Grahamstown Shoprite/Checkers Grahamstown Great Kei Rural Crossways Pharmacy Harding Harding Spar Jeffrey's Bay Dis-Chem Jeffreys Bay Jeffrey's Bay PicknPay Jeffreys Bay Jeffrey's Bay Shoprite/Checkers Jeffreys Bay Mall Jeffrey's Bay Shoprite/Checkers Jeffreys Bay Jeffrey's Bay Spar Jeffreys Bay Kenton-on-Sea Spar Sunshine Coast King William's Town PicknPay King Williams Town King William's Town Shoprite/Checkers Metlife Mall Maclear Spar Maclear Queen Rose Spar 1 Where in the Eastern Cape can I purchase the latest Diabetes Lifestyle Journal? Part 2 City/Town Name of retail outlet Mdantsane PicknPay Mdantsane Middelburg Spar Ons Handels Huis Mthatha Shoprite/Checkers Mthatha Mthatha Shoprite/Checkers Ngebs City Mthatha Super Spar Savoy -

Volunteer Manual

Volunteer Manual heTable of contents: Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................. 3Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................ Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. SUMMARY OF VOLUNTEER PROGRAM .............................. Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. VOLUNTEER ROLE ............................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. LOCATION ........................................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. ACCOMODATION ................................................................ Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. FOOD .................................................................................. Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. THINGS TO DO .................................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. FUNDRAISING ..................................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. HEALTH AND SAFETY .......................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. PACKING ............................................................................. Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. 2 Introduction Volunteering with us is more than being Part of a volunteer Program. It’s the oPPortunity to join the team of TransCape Non Profit Organization and become a member of our community. TransCape is based in the rural communities -

Explore the Eastern Cape Province

Cultural Guiding - Explore The Eastern Cape Province Former President Nelson Mandela, who was born and raised in the Transkei, once said: "After having travelled to many distant places, I still find the Eastern Cape to be a region full of rich, unused potential." 2 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Eastern Cape Module # 1 - Province Overview Component # 1 - Eastern Cape Province Overview Module # 2 - Cultural Overview Component # 1 - Eastern Cape Cultural Overview Module # 3 - Historical Overview Component # 1 - Eastern Cape Historical Overview Module # 4 - Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Component # 1 - Eastern Cape Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Module # 5 - Nelson Mandela Bay Metropole Component # 1 - Explore the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropole Module # 6 - Sarah Baartman District Municipality Component # 1 - Explore the Sarah Baartman District (Part 1) Component # 2 - Explore the Sarah Baartman District (Part 2) Component # 3 - Explore the Sarah Baartman District (Part 3) Component # 4 - Explore the Sarah Baartman District (Part 4) Module # 7 - Chris Hani District Municipality Component # 1 - Explore the Chris Hani District Module # 8 - Joe Gqabi District Municipality Component # 1 - Explore the Joe Gqabi District Module # 9 - Alfred Nzo District Municipality Component # 1 - Explore the Alfred Nzo District Module # 10 - OR Tambo District Municipality Component # 1 - Explore the OR Tambo District Eastern Cape Province Overview This course material is the copyrighted intellectual property of WildlifeCampus.