The Correspondence of William Cowper *> \ the Correspondence of William Cowper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanticism and Evangelical Christianity in William Cowper's the at Sk Carol V

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1976 Romanticism and Evangelical Christianity in William Cowper's The aT sk Carol V. Johnson Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Johnson, Carol V., "Romanticism and Evangelical Christianity in William Cowper's The askT " (1976). Masters Theses. 3394. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3394 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROMANTICISM AND EVANGELICAL CHRISTIANITY I N WILLIAM COWPER'S THE TASK (TITLE) BY CAROL V. JOHNSON B. A., Eastern I llinois University, 1975 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE DATE PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have wr i tten formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. • The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to repr oduc e dissertations for inclusion in their library hold ings . Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a. -

Ecologies of Contemplation in British Romantic Poetry

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 2-2021 The Lodge in the Wilderness: Ecologies of Contemplation in British Romantic Poetry Sean M. Nolan The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4185 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE LODGE IN THE WILDERNESS: ECOLOGIES OF CONTEMPLATION IN BRITISH ROMANTIC POETRY by SEAN NOLAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2021 © 2020 Sean Nolan All Rights Reserved ii The Lodge in the Wilderness: Ecologies of Contemplation in British Romantic Poetry by Sean Nolan This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________ ____________________________________ Date Nancy Yousef Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ ____________________________________ Date Kandice Chuh Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Alexander Schlutz Alan Vardy Nancy Yousef THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Lodge in the Wilderness: Ecologies of Contemplation in British Romantic Poetry by Sean Nolan Advisor: Nancy Yousef This dissertation argues that contemplation is often overlooked in studies of British Romantic poetry. By the late 1700s, changing commercial and agricultural practices, industrialism, secularization, and utilitarianism emphasizing industriousness coalesced to uproot established discourses of selfhood and leisure, and effected crises of individuation in Romantic poetry and poetics. -

Calling William Cowper: a Visit to the Cowper and Newton Museum

Calling William Cowper: A visit to the Cowper and Newton Museum Your sea of troubles you have past, And found the peaceful shore These were the words I included in the March (Cambridgeshire) Grammar School magazine at the end of my last year there. Roman House were the champions. I was their house captain. Wonderful days! Yet it was the rest of the verse which always stuck in my mind: I tempest-toss’d and wreck’d at last, Come home to port no more. (‘To the Reverend Mr. Newton on his return from Ramsgate. October 1780’) Those words made me think more about the man himself. William Cowper, whose father, John Cowper, was chaplain to George the Third, suffered most of his life from what we know now as manic depression. The actor, Stephen Fry, has publicly shared with the media his own battle with such an affliction. When Cowper died in May, 1800, the funeral service at St. Mary Woolnoth in Lombard Street, London, was conducted by the Rev. John Newton. He said that ‘He [Cowper] could give comfort, though he could not receive any himself.’(The Life of John Newton by Richard Cecil). John Newton, author of the hymn ‘Amazing Grace’, was the curate of the church of St Peter and St Paul in Olney from 1764 to 1779. He was Cowper’s firm friend and mentor. They collaborated to write the Olney Hymns. I wanted to see for myself where Cowper lived, where he wrote his poems and letters, and what he did with his time. -

The Tradition of Theriophily in Cowper, Crabbe, and Burns

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 The rT adition of Theriophily in Cowper, Crabbe, and Burns. Rosemary Moody Canfield Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Canfield, Rosemary Moody, "The rT adition of Theriophily in Cowper, Crabbe, and Burns." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2034. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2034 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72-3470 CANFIELD, Rosemary Moody, 1927- THE TRADITION OF THERIOPHILY IN COWPER, CRABBE, AND BURNS. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, A \ERQX Company , Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED The Tradition of Theriophily in Cowper, Crabbe, and Burns A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Rosemary Moody Canfield B.A., University of Minnesota, 1949 M.A., University of Minnesota, 1952 August, 1971 PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages have indistinct print. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TITLE P A G E .............................................. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT........................................ ii ABSTRACT ............................................... iv I. INTRODUCTION....................................... 1 II. THERIOPHILY IN THE WORK OFWILLIAM COWPER . -

The Second Edition of Cowper's Homer

Widmer, M. (2019) The second edition of Cowper's Homer. Translation and Literature, 28(2-3), pp. 151-199. (doi:10.3366/tal.2019.0384) There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/199006/ Deposited on: 28 October 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 The Second Edition of Cowper’s Homer Matthias Widmer William Cowper’s 1791 translation of the Iliad and Odyssey is rarely read today even among academics. While it adds to the advances in the medium of blank verse that the poet had made with The Task, its literary significance pales by comparison with that of the monumental Pope translation it sought to replace, and as an attempt at rendering Homer it is marred by the unwholesome influence of Milton – or so the general consensus seems to be. As early as 1905, one editor pronounced the translation ‘dead’.1 Cowper’s efforts to revise the text, which continued until the end of his life, are even less well known; the second edition, published posthumously in 1802 by his kinsman John Johnson, has received almost no attention at all. When critics do discuss Cowper’s Homer, it is to the first edition that they refer. Matthew Arnold, although aware of the 1802 edition and Cowper’s dissatisfaction with his earlier work expressed in the preface to that volume, nevertheless quotes the original 1791 version to illustrate what he perceives as the translator’s ‘elaborate Miltonic manner, entirely alien to the flowing rapidity of Homer’:2 So num’rous seem’d those fires the bank between Of Xanthus, blazing, and the fleet of Greece, In prospect all of Troy3 In Arnold’s opinion, ‘the inversion and pregnant conciseness of Milton’ that Cowper imitates in this passage ‘are the very opposites of the directness and flowingness of Homer’ (p. -

Copyright © 2016 Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. All Rights Reserved. The

Copyright © 2016 Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. THE PREACHING OF JOHN NEWTON (1725-1807): A GOSPEL-CENTRIC, PASTORAL HOMILETIC OF BIBLICAL EXPOSITION __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. May 2016 APPROVAL SHEET THE PREACHING OF JOHN NEWTON (1725-1807): A GOSPEL-CENTRIC, PASTORAL HOMILETIC OF BIBLICAL EXPOSITION Larry Wren Sowders, Jr. Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Hershael W. York (Chair) __________________________________________ Robert A. Vogel __________________________________________ Michael A. G. Haykin Date______________________________ I dedicate this dissertation to my wife, Angela, whose faithfulness, diligence, and dedicated service to Christ and to others never cease to amaze and inspire me. “Many daughters have done nobly, but you excel them all.” (Prov 31:29) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . vi Chapter 1. THE STUDY OF JOHN NEWTON AND HIS PREACHING . 1 Introduction . 1 Thesis . 6 Background . 7 Methodology . 8 Summary of Content . 11 2. NEWTON’S LIFE AND MINISTRY . 14 Early Years and Life at Sea . 14 Africa and Conversion . 16 Marriage and Call to Ministry . 19 Ministry in Olney and London . 25 Final Years and Death . 33 3. NEWTON’S PREACHING AND THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY . 36 An Overview of Newton’s Preaching . 36 The Eighteenth-Century Context . 54 The Pulpit in Eighteenth-Century England . 58 4. -

George Herbert, William Cowper, and the Discourse of Dis/Ability1

‘Upon the Rack’: George Herbert, William Cowper, and the Discourse of Dis/ability1 In 1876, George Herbert and William Cowper were jointly memorialized on a window in St. George’s Chapel in Westminster Abbey2. This placement of the portraits of ‘Herbert at Bemerton, and Cowper at Olney’ side by side seems natural given their shared history as students at Westminster school and Cowper’s high regard for Herbert’s spiritual vision3. It is true that Cowper describes Herbert’s poetic style as ‘gothic and uncouth’ in his spiritual autobiography, Adelphi, echoing the late Augustan view of Herbert’s poems as outmoded and unpolished4. However, here and elsewhere, Cowper is adamant that Herbert’s poetry is therapeutic for those on the ‘Brink’ of ‘Ruin’5. Although Cowper shares the emotional volatility of John Donne – from whom his mother, Ann Donne, claimed descent – it is in the poems of Herbert that he finds a restorative agent for the suffering body and spirit6. During one of Cowper’s earliest depressive episodes, he describes suffering ‘day and night […] upon the rack, lying down in horrors and rising in despair’, finding a measure of relief only in the poems of Herbert. Immersing himself in them ‘all day long’, he finds ‘delight’ in their ‘strain of piety’7. Though Cowper admits that the poems do not completely cure his ailment, in the act of reading them, his dis/abled mind is ‘much alleviated’8. Cowper returns to Herbert’s poetry later in life when he finds his brother John near death and possibly damnation9. When John is so ill that ‘his case is clearly out of the Reach of Medicine’, Cowper again succumbs to a psychological panic that only Herbert can assuage. -

"Baptists and Independents in Olney to the Time of John Newton," 26-37

26 BAPTISTS AND INDEPENDENTS IN OLNEY TO THE TIME OF JOHN NEWTON Dissent in Olney owed its origin to John Gibbs, the ejected Rector of the neighbouring Newport Pagnell, who in 1669 was reported as leading an "Anabaptist" meeting in Olney. Gibbs was a man to be reckoned with, a man of convictions, with literary ability and political sense, and also the wherewithal to give expression to them. But he did not live in Olney. He settled in Newport as the minister of the Dissenting church in that town and remained there till his death in 1699, aged 72: his tombstone, with an inscription in Eng1ish, cut recently in place of the original Latin, which had decayed, may be seen outside the south wall of the parish church. Olney was only one of a number of places where Gibbs was active, and where a body of Dissenters, which sometimes persisted and sometimes died out, owed its existence to him. Newton Blossomville to the East of Olney and Astwood to the South-East, Cranfield in Bedfordshire and Roade in Northamptonshi~e were others. Gibbs was also in touch with the church in Bedford, and with Bunyan. The work at Olney was carried on by an apothecary associ ated with Gibbs, named Thomas Bere (Bear, Beard, Bard). In 1662 he had been elected one of the four elders of the church in Cambridge ministered to by Francis Holcroft (d.1692), the ejected Vicar of Bassingbourne; but he "fell under· som surcom stance that he left the church". "Oni church" then took him "into their sosieti". -

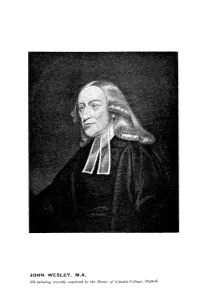

JOHN WESLEV, M.A. Oit Pat"Niing Yf'ceutly Acquired by the Rector of L£Ucoln College, Oxford

JOHN WESLEV, M.A. Oit pat"niing Yf'ceutly acquired by the Rector of L£ucoln College, Oxford. PROCitEDINGS, ANOTHER PORTRAIT OF JOHN WESLEY AT LINCOLN COLLEGE, OXFORD· The Rector of Lincoln College has recently acquired a portrait of John Wesley of which he kindly sends us a photograph. At present the name of the painter appears to be unknown. For purposes of comparison we have sent to Oxford copies of the best known portraits of Wesley in his later years, including two of Romney's (1789), Hamilton's (1789), and Jackson's well known synthetic portrait, painted in 1827. · The Rector suggest! that in some respects the newly discovered portrait resembles Hamilton's. The writer of this note asks : is it a replica by Jackson, or a copy of his original painting at the 1 Book Room '? It is uncertain who possessed it before it came into the hands of 1 a dealer'. Can any member of the W. H. S. throw light upon it? We have not yet seen the oil painting itself. If some reader is able to do so, with the Rector's permission, he will want to compare it with other portraits. The critic will know something of technique, of composition, and colour. He will be able to discern what pigments were used by the painter. He will enquire if on the painting, or canvass, or frame, there is any trace of a name, or date. He may recall Ruskin's saying (in Modern Painter1), 1 there is not the face which the painter may not make ideal if he choose ; but that subtle feeling which shall find out all of good that there is in any given countenance is not, except by concern for other things than art, to be acquired.' He will agree with P. -

Professor Ff Bruce, Ma, Dd the Inextinguishable Blaze

The Paternoster Ch11rch History, Vol. VII General Editor: PROFESSOR F. F. BRUCE, M.A., D.D. THE INEXTINGUISHABLE BLAZE In the Same Series: Vol. I. THE SPREADING FLAME The Rise and Progress of Christianity l!J Professor F. F. Bruce, M.A., D.D. Vol. II. THE GROWING STORM SketrhesofChurchHistoryfromA.D. 6ootoA.D. IJJO i!J G. S. M. Walker, M.A., B.D., Ph.D. Vol. III. THE MORNING STAR Wycliffe and the Dawn of the Reformation l!J G. H. W. Parker, M.A., M.Litt. Vol. VI. LIGHT IN THE NORTH The Story of the Scottish Covenanters l!J J. D. Douglas, M.A., B.D., S.T.M., Ph.D. Vol. VIII. THE LIGHT OF THE NATIONS Evangelical Renewal and Advance in the Nineteenth Century l!JJ. Edwin Orr, Ph.D., D. Phil. (Oxon), F.R.Hist.S. In Preparation: Vol. IV. THE GREAT LIGHT Luther and the Reformation l!J James Atkinson, M.A., M.Litt., D.Th. Vol. V. THE REFINING FIRE The Puritan Era l!J James Packer, M.A., D.Phil. THE INEXTINGUISHABLE BLAZE SpiritlltlJ Renewal and Advance in the Eighteenth Century by A. SKEVINGTON WOOD B.A., Ph.D., F.R.Hist.S. Then let it for Thy glory h11r11 With inextingllishahle bla:<.e,· And trembling to its source return, In humble prayer and fervent praise. Charles Wesley PATERNOSTER • THE PATERNOSTER PRESS C Copyright 1900 The Patm,oster Press Second impru.rion Mar,h 1967 AUSTRALIA: Emu Book Agmriu Pty., Ltd., pr, Kent Streit, Sydney, N.S.W. CANADA: Hom, E11angel Books Ltd., 2.5, Hobson A11enue, Toronto, 16 SOUTH AFRICA: Oxford University Prus, P.O.Box u41, Thibault Ho11.re, Thibault Square, Cape Town NEW ZEALAND: G. -

Private Sources at the National Archives

Private Sources at the National Archives Small Private Accessions 1972–1997 999/1–999/850 1 The attached finding-aid lists all those small collections received from private and institutional donors between the years 1972 and 1997. The accessioned records are of a miscellaneous nature covering testamentary collections, National School records, estate collections, private correspondence and much more. The accessioned records may range from one single item to a collection of many tens of documents. All are worthy of interest. The prefix 999 ceased to be used in 1997 and all accessions – whether large or small – are now given the relevant annual prefix. It is hoped that all users of this finding-aid will find something of interest in it. Paper print-outs of this finding-aid are to be found on the public shelves in the Niall McCarthy Reading Room of the National Archives. The records themselves are easily accessible. 2 999/1 DONATED 30 Nov. 1972 Dec. 1775 An alphabetical book or list of electors in the Queen’s County. 3 999/2 COPIED FROM A TEMPORARY DEPOSIT 6 Dec. 1972 19 century Three deeds Affecting the foundation of the Loreto Order of Nuns in Ireland. 4 999/3 DONATED 10 May 1973 Photocopies made in the Archivio del Ministerio de Estado, Spain Documents relating to the Wall family in Spain Particularly Santiago Wall, Conde de Armildez de Toledo died c. 1860 Son of General Santiago Wall, died 1835 Son of Edward Wall, died 1795 who left Carlow, 1793 5 999/4 DONATED 18 Jan. 1973 Vaughan Wills Photocopies of P.R.O.I. -

Faith@Work the Magazine of Glenrothes Baptist Church

faith@work the magazine of glenrothes baptist church march 2015 [1] Contents page THE PASTOR’S PAGES: LET US PRAY 1 HOLY WEEK SERVICES 8 BAPTISMS 9 FROM THE TREASURER 14 AN INTRODUCTION TO GBC 15 MISSION JAKARTA 18 SCOTTISH REFORMED CONFERENCE 26 ‘LORD, FOR THE YEARS’ 27 CONNECTED BY GRACE—JOHN THORNTON (2) 29 OUR ANNIVERSARY PREACHER 37 [2] The Pastor’s Pages LET US PRAY ur church is strong at many things. God Ohas given our church a heart to love and to reach out to others. We spend much time doing many great ministries and services to others within and without the church. We love the Word of God and proclaiming the gospel of Jesus Christ to the nations. We don’t shrink from proclaiming central doctrines, and ‘contending for the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints.’ We strive together to make disciples who make disciples. We seek to serve together using all of the different gifts of the body of the church, that Christ may be glorified. God is definitely at work among us. He is growing our church, and not only numerically. Souls are being saved, and all Christians (young & old) are growing in depth of insight and understanding in following Christ. However, I can’t help but think this is in spite of us— particularly when I consider our church’s heart for corporate prayer. Now, I’m not saying that we don’t pray. I’m sure as individuals and with friends we do pray a lot (I hope I’m not giving everyone the benefit of the doubt).