Rob Ninkovich, Linebacker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ty Law: Why This Pro Football Hall of Famer and Successful Entrepreneur Bets on Himself

SEEKING THE EXTRAORDINARY Ep 3 - Ty Law: Why this Pro Football Hall of Famer and Successful Entrepreneur Bets on Himself FEB 9, 2021 [00:00:00] Michael Nathanson: [00:00:00] Welcome fellow seekers of the extraordinary. Welcome to our shared quest, a quest, not for a thing, but for an ideal, a quest, not for a place, but into the inner unexplored regions of ourselves, a quest to understand how we can achieve our fullest potential by learning from others who have done or are doing exactly that. May we always have the courage and wisdom to learn from those who have something to teach. Join me now in seeking the extraordinary. I’m Michael Nathanson, your chief secret of the extraordinary. Today’s guest is the founder of the high- ly popular Launch trampoline parks, a serial entrepreneur. He’s now an equity owner of V1 vodka, but you may know him better for his 15 years in the NFL. He won three super bowls. As part of the New England Patriots, he was selected for five pro bowls and was a pro bowl MVP. His 53 career interceptions are among the [00:01:00] best in NFL history, making him one of the best cornerbacks of all time. He’s a member of the 2019 class of inductees into the NFL Hall of Fame, joining only 325 other members in this most special achievement, please welcome the extraordinary. Ty Law. Ty, welcome. Ty Law: [00:01:21] Thank you. I like the intro. I liked the intro. -

Instant Replay: a Round-Up of 1991 Clean up an Alleged Landfill, Spilled Tower on Lopez Road, an the British Invasion of Wilmington by Arlene Surprcnant MWRA

- ■' \s> Irtaksbunj - ffltlminqtiui 37TH YEAR NO 1 (508) 658-2346 PUB. NO. 635-340 WILMINGTON, MASS, JANUARY 1, 1992 ■* Copyright 1992. Wilmington News Co., Inc. 2VPAGES State approves historic district by Arlene Surprcnant Street down Middlesex Avenue and Wilmington's Center Village "a sure thing" for towns applying district and the number of schools as Historic District has been Church Street to Wildwood for the National Register. Cemetery. The 110 acre area well. These include the Buzzcll unanimously approved by the Along with Lafionatis, there arc School, the Swain School and the Massachusetts Historical Commis- encompasses 33 buildings and sites six other members on the William Blanchard Jr. House. Of all sion for inclusion into the National including the town pound and old commission. They are Chairman cemetery. the buildings within the area, 21 arc Register of Historic Places. The Carolyn Harris, Kevin Backman, owned by private citizens. Once the town's application will now be "I'm delighted about it," said Jim Murray, Jean Rowc, Jean Rylc district is placed in the National reviewed by Department of Interior Dorothy Lafionatis, a veteran and Frank West. Register, private owners with in Washington D.C. for final member of the local historical According to Harris, commis- income producing property arc approval. * commission which worked over sioners felt confident they could eligible for federal tax incentives The district covers the area several years to gain recognition for succeed with their application and rehabilitation aid. There arc surrounding Wilmington Town the district. Lafionatis pointed out mainly because of the number of also grants available for historic Common and runs from Adams that the state's acceptance usually is 18th and 19th century homes in the restoration. -

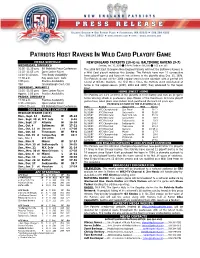

Patriots Host Ravens in Wild Card Playoff Game

PATRIOTS HOST RAVENS IN WILD CARD PLAYOFF GAME MEDIA SCHEDULE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (10-6) vs. BALTIMORE RAVENS (9-7) WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6 Sunday, Jan. 10, 2010 ¹ Gillette Stadium (68,756) ¹ 1:00 p.m. EDT 10:50 -11:10 a.m. Bill Belichick Press Conference The 2009 AFC East Champion New England Patriots will host the Baltimore Ravens in 11:10 -11:55 a.m. Open Locker Room a Wild Card playoff matchup this Sunday. The Patriots have won 11 consecutive 11:10-11:20 p.m. Tom Brady Availability home playoff games and have not lost at home in the playoffs since Dec. 31, 1978. 11:30 a.m. Ray Lewis Conf. Calls The Patriots closed out the 2009 regular-season home schedule with a perfect 8-0 1:05 p.m. Practice Availability record at Gillette Stadium. The first three times the Patriots went undefeated at TBA Jim Harbaugh Conf. Call home in the regular-season (2003, 2004 and 2007) they advanced to the Super THURSDAY, JANUARY 7 Bowl. 11:10 -11:55 p.m. Open Locker Room HOME SWEET HOME Approx. 1:00 p.m. Practice Availability The Patriots are 11-1 at home in the playoffs in their history and own an 11-game FRIDAY, JANUARY 8 home winning streak in postseason play. Eleven of the franchise’s 12 home playoff 11:30 a.m. Practice Availability games have taken place since Robert Kraft purchased the team 16 years ago. 1:15 -2:00 p.m. Open Locker Room PATRIOTS AT HOME IN THE PLAYOFFS (11-1) 2:00-2:15 p.m. -

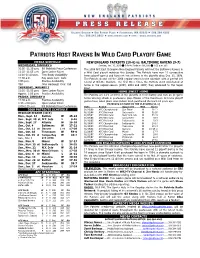

Patriots Host Ravens in Wild Card Playoff Game

PATRIOTS HOST RAVENS IN WILD CARD PLAYOFF GAME MEDIA SCHEDULE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (10-6) vs. BALTIMORE RAVENS (9-7) WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6 Sunday, Jan. 10, 2010 ¹ Gillette Stadium (68,756) ¹ 1:00 p.m. EDT 10:50 -11:10 a.m. Bill Belichick Press Conference The 2009 AFC East Champion New England Patriots will host the Baltimore Ravens in 11:10 -11:55 a.m. Open Locker Room a Wild Card playoff matchup this Sunday. The Patriots have won 11 consecutive 11:10-11:20 p.m. Tom Brady Availability home playoff games and have not lost at home in the playoffs since Dec. 31, 1978. 11:30 a.m. Ray Lewis Conf. Calls The Patriots closed out the 2009 regular-season home schedule with a perfect 8-0 1:05 p.m. Practice Availability record at Gillette Stadium. The first three times the Patriots went undefeated at TBA John Harbaugh Conf. Call home in the regular-season (2003, 2004 and 2007) they advanced to the Super THURSDAY, JANUARY 7 Bowl. 11:10 -11:55 p.m. Open Locker Room HOME SWEET HOME Approx. 1:00 p.m. Practice Availability The Patriots are 11-1 at home in the playoffs in their history and own an 11-game FRIDAY, JANUARY 8 home winning streak in postseason play. Eleven of the franchise’s 12 home playoff 11:30 a.m. Practice Availability games have taken place since Robert Kraft purchased the team 16 years ago. 1:15 -2:00 p.m. Open Locker Room PATRIOTS AT HOME IN THE PLAYOFFS (11-1) 2:00-2:15 p.m. -

African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: a Qualitative Study on Turning Points

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: A Qualitative Study on Turning Points Thaddeus Rivers University of Central Florida Part of the Educational Leadership Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rivers, Thaddeus, "African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: A Qualitative Study on Turning Points" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1469. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1469 AFRICAN AMERICAN HEAD FOOTBALL COACHES AT DIVISION I FBS SCHOOLS: A QUALITATIVE STUDY ON TURNING POINTS by THADDEUS A. RIVERS B.S. University of Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in the Department of Child, Family and Community Sciences in the College of Education and Human Performance at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2015 Major Professor: Rosa Cintrón © 2015 Thaddeus A. Rivers ii ABSTRACT This dissertation was centered on how the theory ‘turning points’ explained African American coaches ascension to Head Football Coach at a NCAA Division I FBS school. This work (1) identified traits and characteristics coaches felt they needed in order to become a head coach and (2) described the significant events and people (turning points) in their lives that have influenced their career. -

01 12 Recruiting.Indd

UUCLACLA - TThehe CCompleteomplete PPackageackage “UCLA has the most complete athletic program in the country” (Sports Illustrated On Campus - April ‘05 The Nation’s No. 1 Combined Academic, Social & Athletic Program Winner of more NCAA Championships than any other school; one of the nation’s top public universities; centrally located to beaches and mountains. An Outstanding Head Coach Jim Mora is a former NFC Coach of the Year with 25 seasons of NFL coaching experience. He has served as Head Coach of the Atlanta Falcons and the Seattle Seahawks and as the defen- sive coordinator of the San Francisco 49ers. Talented & Experienced Coaching Staff An experienced staff with diverse backgrounds, many with NFL experience as coaches and players. The goal of the staff is to develop greatness in UCLA’s student-athletes, both on and off the fi eld. Academic Support Learning specialists, tutoring aid, counseling and general assistance that is second to none. The Bruin Family UCLA provides a prosperous outlook for the future with internships, workshop mentoring programs and access to one of the world’s meccas of business, entertainment, media and networking. Media Rich Southern California USA Today, Fox Sports Net, NFL Network and ESPN have offi ces in LA. Seven local television stations and 13 area newspapers provide unparalleled coverage. The Next Step Over 25 Bruins populate NFL rosters on a yearly basis. At least one former Bruin has been on the roster of a Super Bowl team in 29 of the last 32 years. In 29 of the last 30 seasons, at least one Bruin has made a Pro Bowl roster. -

Rams Patriots Rams Offense Rams Defense

New England Patriots vs Los Angeles Rams Sunday, February 03, 2019 at Mercedes-Benz Stadium RAMS RAMS OFFENSE RAMS DEFENSE PATRIOTS No Name Pos WR 83 J.Reynolds 11 K.Hodge DE 90 M.Brockers 94 J.Franklin No Name Pos 4 Zuerlein, Greg K TE 89 T.Higbee 81 G.Everett 82 J.Mundt NT 93 N.Suh 92 T.Smart 69 S.Joseph 2 Hoyer, Brian QB 6 Hekker, Johnny P 3 Gostkowski, Stephen K 11 Hodge, Khadarel WR LT 77 A.Whitworth 70 J.Noteboom DT 99 A.Donald 95 E.Westbrooks 6 Allen, Ryan P 12 Cooks, Brandin WR LG 76 R.Saffold 64 J.Demby WILL 56 D.Fowler 96 M.Longacre 45 O.Okoronkwo 11 Edelman, Julian WR 14 Mannion, Sean QB 12 Brady, Tom QB 16 Goff, Jared QB C 65 J.Sullivan 55 Br.Allen OLB 50 S.Ebukam 53 J.Lawler 49 T.Young 13 Dorsett, Phillip WR 17 Woods, Robert WR RG 66 A.Blythe ILB 58 C.Littleton 54 B.Hager 59 M.Kiser 15 Hogan, Chris WR 19 Natson, JoJo WR 18 Slater, Matt WR 20 Joyner, Lamarcus S RT 79 R.Havenstein ILB 26 M.Barron 52 R.Wilson 21 Harmon, Duron DB 21 Talib, Aqib CB WR 12 B.Cooks 19 J.Natson LCB 22 M.Peters 37 S.Shields 31 D.Williams 22 Melifonwu, Obi DB 22 Peters, Marcus CB 23 Chung, Patrick S 23 Robey, Nickell CB WR 17 R.Woods RCB 21 A.Talib 32 T.Hill 23 N.Robey 24 Gilmore, Stephon CB 24 Countess, Blake DB QB 16 J.Goff 14 S.Mannion SS 43 J.Johnson 24 B.Countess 26 Michel, Sony RB 26 Barron, Mark LB 27 Jackson, J.C. -

2016 Florida Football Postgame Notes Tennessee 38, Florida 28 September 24, 2016

2016 Florida Football Postgame Notes Tennessee 38, Florida 28 September 24, 2016 Saturday’s Highlights Florida scored on its first drive of the game, a feat last accomplished October 15, 2015 vs Missouri (11 games) Florida’s second scoring drive was a season-long 93 yards In the last 13 quarters, opposing quarterbacks thrown six interceptions against Florida’s passing defense. In the past three seasons, Tennessee QBs have completed just 13 passes and been sacked seven times on third down vs Florida (Per ESPN Stats & Info) Florida Offense In his first career start for Florida, RS senior Austin Appleby threw for 296 yards, which is third-most for a UF quarterback in his first start since 1990. o Trailing Shane Matthews (332) and Tim Tebow (300) Jordan Cronkrite caught his first receiving touchdown since November 14, 2015 vs South Carolina (7 games) After scoring three touchdowns as a freshman, Jordan Scarlett has three rushing touchdowns through four games this season DeAndre Goolsby’s touchdown catch in the first quarter was his first of the season, and second of his career Freshman Tyrie Cleveland’s first career catch was a 36 yard pass in the second quarter Freshman Freddie Swain caught his second touchdown pass of the season With 134 receiving yards today, Antonio Callaway has now eclipsed 1,000 yards for his career (1,013 ) o Callaway is tied for the third-fastest player in Florida history to reach 1,000 receiving yards. (17 games) After only posting four passing plays of 50-plus yards in 2015, Florida already has 3 such passing plays this season. -

Tarvaris Jackson Can't Obtain Buffet 12 Times This Week If He's Going to Acquaint It Amongst the Game

Tarvaris Jackson can't obtain buffet 12 times this week if he's going to acquaint it amongst the game. (AP Photo/Elaine Thompson) (AP) Marshawn Lynch has struggled to find apartment to escape this season. (AP Photo/Elaine Thompson) (ASSOCIATED PRESS) Tony Romo wasn't great last week against the Eagles. (AP Photo/Michael Perez) (AP) DeMarcus Ware is an of the most dangerous pass rushers surrounded the NFL. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez, File) (ASSOCIATED PRESS) Miles Austin was quiet last week,anyhow the Seahawks ambition have their hands full with him aboard Sunday. (AP Photo/Sharon Ellman) (AP) Seahawks along Cowboys: 5 things to watch WHAT: Seattle Seahawks (2-5) along Dallas Cowboys (3-4) (Week nine) WHEN: 10 a.m. PT Sunday WHERE: Cowboys Stadium, Dallas, Texas TV/RADIO: FOX artery 13 among Seattle) / 710 AM, 97.three FM What to watch for 1,boise state football jersey. Protect the pectoral Tarvaris Jackson is probable to activity Sunday, so expect him to begin as quarterback as the Seahawks. But don??t be also surprised whether he can??t withstand the same volume and ferocity of hits we??ve become accustomed to seeing. Coach Pete Carroll indicated Friday that meantime Jackson is healthy enough to activity he??s still a ways from being after to where he was pre-injury. ??He does not feel great,?? Carroll said Friday. ??He??s but making it through practice.?? Of lesson ??barely?? making it is still making it, and with the access Charlie Whitehurst has performed this season, it??s likely that the Seahawks will do whatever they can to reserve Jackson on the field. -

Final Rosters

Rosters 2001 Final Rosters Injury Statuses: (-) = OK; P = Probable; Q = Questionable; D = Doubtful; O = Out; IR = On IR. Baltimore Hownds Owner: Zack Wilz-Knutson PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR There are no players on this team's week 17 roster. Houston Stallions Owner: Ian Wilz PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR Dave Brown QB ARI - Jake Plummer QB ARI - Tim Couch QB CLE - Duce Staley RB PHI - Ricky Watters RB SEA IR Ron Dayne RB NYG - Stanley Pritchett RB CHI - Zack Crockett RB OAK - Derrick Mason WR TEN - Johnnie Morton WR DET - Laveranues Coles WR NYJ - Willie Jackson WR NOR - Alge Crumpler TE ATL - Dave Moore TE TAM - Matt Stover K BAL - Paul Edinger K CHI - 2001 Final Rosters 1 Rosters Chicago Bears Defense CHI - Pittsburgh Steelers Defense PIT - Carolina Panthers Special Team CAR - Dallas Cowboys Special Team DAL - Dan Reeves Head Coach ATL - Dick Jauron Head Coach CHI - NYC Dark Force Owner: D.J. Wendell NFL ON PLAYER POSITION INJ STARTER RESERVE TEAM IR Aaron Brooks QB NOR - Daunte Culpepper QB MIN - Jeff Blake QB NOR - Bob Christian RB ATL - Emmitt Smith RB DAL - James Stewart RB DET - Jim Kleinsasser RB MIN - Warrick Dunn RB TAM - Cris Carter WR MIN - James Thrash WR PHI - Jerry Rice WR OAK - Travis Taylor WR BAL - Dwayne Carswell TE DEN - Jay Riemersma TE BUF - Jay Feely K ATL - Joe Nedney K TEN - San Francisco 49ers Defense SFO - Defense TAM - 2001 Final Rosters 2 Rosters Tampa Bay Buccaneers Minnesota Vikings Special Team MIN - Oakland Raiders Special Team OAK - Dick Vermeil Head Coach KAN - Steve Mariucci Head Coach SFO - Las Vegas Owner: ?? PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR There are no players on this team's week 17 roster. -

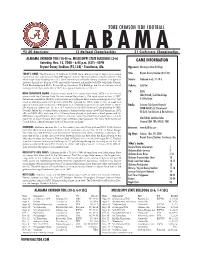

2008 Alabama FB Game Notes

2008 CRIMSON TIDE FOOTBALL 92 All-Americans ALABAMA12 National Championships 21 Conference Championships ALABAMA CRIMSON TIDE (10-0) vs. MISSISSIPPI STATE BULLDOGS (3-6) GAME INFORMATION Saturday, Nov. 15, 2008 - 6:45 p.m. (CST) - ESPN Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) - Tuscaloosa, Ala. Opponent: Mississippi State Bulldogs TODAY’S GAME: The University of Alabama football team returns home to begin a two-game Site: Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) homestand that will close out the 2008 regular season. The top-ranked Crimson Tide host the Mississippi State Bulldogs in a SEC West showdown at Bryant-Denny Stadium. The game is Series: Alabama leads, 71-18-3 slated to kickoff at 6:45 p.m. (CST) and will be televised nationally by ESPN with Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge and Holly Rowe calling the action. The Bulldogs are 3-6 on the season and Tickets: Sold Out coming off of a bye week after a 14-13 loss against Kentucky on Nov. 1. TV: ESPN HEAD COACH NICK SABAN: Alabama head coach Nick Saban (Kent State, 1973) is in his second season with the Crimson Tide. He was named the school’s 27th head coach on Jan. 3, 2007. Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge Saban has compiled a 108-48-1 (.691) record as a collegiate head coach, including an 17-6 (.739) & Holly Rowe mark at Alabama and a 10-0 record in 2008. He captured his 100th career victory in week two against Tulane and coached his 150th game as a collegiate head coach in week three vs. West- Radio: Crimson Tide Sports Network ern Kentucky. -

New York Jets Vs. New England Patriots

No. Name Pos. No. Name Pos. 3 David Fales QB 2 Mike Nugent K 4 Lachlan Edwards P 4 Jarrett Stidham QB 9 Sam Ficken K NEW YORK JETS VS. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS 7 Jake Bailey P 10 Braxton Berrios WR 10 Josh Gordon WR 11 Robby Anderson WR 11 Julian Edelman WR 14 Sam Darnold QB 12 Tom Brady QB 15 Josh Bellamy WR MONDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2019 • NEWYORKJETS.COM • @NYJETS • @NYJETSPR 13 Phillip Dorsett II WR 17 Vyncint Smith WR 16 Jakobi Meyers WR 18 Demaryius Thomas WR JETS OFFENSE JETS DEFENSE 18 Matthew Slater WR 20 Marcus Maye S 21 Duron Harmon DB WR 11 Robby Anderson 17 Vyncint Smith DL 92 Leonard Williams 94 Folorunso Fatukasi 60 Jordan Willisi 21 Nate Hairston CB 23 Patrick Chung S 22 Trumaine Johnson CB LT 68 Kelvin Beachum 69 Conor McDermott DL 99 Steve McLendon 95 Quinnen Williams 24 Stephon Gilmore CB 25 Trenton Cannon RB LG 70 Kelechi Osemele 71 Alex Lewis DL 96 Henry Anderson 98 Kyle Phillips 25 Terrence Brooks DB 26 Le’Veon Bell RB C 55 Ryan Kalil 78 Jonotthan Harrison OLB 48 Jordan Jenkins 93 Tarell Basham 26 Sony Michel RB 27 Darryl Roberts CB RG 67 Brian Winters 77 Tom Compton ILB 57 C.J. Mosley 47 Albert McClellan 27 J.C. Jackson DB 29 Bilal Powell RB RT 75 Chuma Edoga 72 Brandon Shell ILB 46 Neville Hewitt 53 Blake Cashman 28 James White RB 32 Blake Countess S 30 Jason McCourty CB TE 89 Chris Herndon 84 Ryan Griffin 87 Daniel Brown OLB 51 Brandon Copeland 44 Harvey Langi 33 Jamal Adams S 31 Jonathan Jones DB 34 Brian Poole CB 85 Trevon Wesco CB 22 Trumaine Johnson 21 Nate Hairston 32 Devin McCourty DB 41 Matthias Farley S WR 82 Jamison