Aristotle's Philosophy and the Problem of Universals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Western Philosophy: the European Emergence

Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series I, Culture and Values, Volume 9 History of Western Philosophy by George F. McLean and Patrick J. Aspell Medieval Western Philosophy: The European Emergence By Patrick J. Aspell The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy 1 Copyright © 1999 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Gibbons Hall B-20 620 Michigan Avenue, NE Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Aspell, Patrick, J. Medieval western philosophy: the European emergence / Patrick J. Aspell. p.cm. — (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series I. Culture and values ; vol. 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Philosophy, Medieval. I. Title. III. Series. B721.A87 1997 97-20069 320.9171’7’090495—dc21 CIP ISBN 1-56518-094-1 (pbk.) 2 Table of Contents Chronology of Events and Persons Significant in and beyond the History of Medieval Europe Preface xiii Part One: The Origins of Medieval Philosophy 1 Chapter I. Augustine: The Lover of Truth 5 Chapter II. Universals According to Boethius, Peter Abelard, and Other Dialecticians 57 Chapter III. Christian Neoplatoists: John Scotus Erigena and Anselm of Canterbury 73 Part Two: The Maturity of Medieval Philosophy Chronology 97 Chapter IV. Bonaventure: Philosopher of the Exemplar 101 Chapter V. Thomas Aquinas: Philosopher of the Existential Act 155 Part Three: Critical Reflection And Reconstruction 237 Chapter VI. John Duns Scotus: Metaphysician of Essence 243 Chapter -

Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife Hyde Dawn Krista University of Missouri-St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Theses Graduate Works 4-16-2012 Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife Hyde Dawn Krista University of Missouri-St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Krista, Hyde Dawn, "Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife" (2012). Theses. 261. http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis/261 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife Krista Hyde M.L.A., Washington University in St. Louis, 2010 B.A., Philosophy, Southeast Missouri State University – Cape Girardeau, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to The Graduate School at the University of Missouri – St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Philosophy April 2012 Advisory Committee Gualtiero Piccinini, Ph.D. Chair Jon McGinnis, Ph.D. John Brunero, Ph.D. Copyright, Krista Hyde, 2012 Abstract Thomas Aquinas nearly succeeds in addressing the persistent problem of the mind-body relationship by redefining the human being as a body-soul (matter-form) composite. This redefinition makes the interaction problem of substance dualism inapplicable, because there is no soul “in” a body. However, he works around the mind- body problem only by sacrificing an immaterial afterlife, as well as the identity and separability of the soul after death. Additionally, Thomistic psychology has difficulty accounting for the transmission of universals, nor does it seem able to overcome the arguments for causal closure. -

Medieval Philosophy

| 1 Course Syllabus Medieval Philosophy INSTRUCTOR INFORMATION Dr. Wm Mark Smillie, Professor, Philosophy Department 142 St Charles Hall Email: [email protected]; Ph: 447 - 5416 Office Hours Spring 2017 : MW, 3:30 - 4:30; Th, 2:30 - 4:30; Fri, 2:00 - 3:30; & by appointment. For issues about this course, students can contact me before/after class, at my office hours (posted above), by phone or email (either Carroll email or through moodle email). I will respond to email and phone inquiries within one busine ss day (Saturdays and Sundays are not business days). I will post notifications about the course in the Moodle News Forum. Students should also be aware of the Moodle Calendar that announces assignment deadlines. COURSE INFORMATION PHIL202, Medieval Phil osophy Meets: Tuesday and Thursdays, 9:30 - 10:45, 102 O’Connell; 3 credit hours Course Description This course is an introductory survey of medieval philosophical thought. We will consider some philosophical questions and issues that were central to medieval discussion, including the relationship between faith and reason, the problem of evil, our abili ty to know God’s nature and describe it in human language, the implications of believing in God as a creator, and the famous “problem of universals.” Significant medieval philosophers studied in this course include St. Augustine, Boethius, Peter Abelard, St. Anselm, Avicenna, St. Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure. An effort will be made to convey general medieval life and values and their connection to medieval philosophy, as well as to relate the thought of the middle Ages to the philosophy of other historic al periods. -

![The Problem of Universals in Contemporary Philosophy∗ Scuola Normale Superiore [Pisa - July 5, 2010]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2044/the-problem-of-universals-in-contemporary-philosophy-scuola-normale-superiore-pisa-july-5-2010-612044.webp)

The Problem of Universals in Contemporary Philosophy∗ Scuola Normale Superiore [Pisa - July 5, 2010]

93 Reportage 7 novembre 2010 International conference on Ontology The problem of universals in contemporary philosophy∗ Scuola Normale Superiore [Pisa - July 5, 2010] Gianmarco Brunialti Masera Overview The three-day conference opened in the afternoon of July, 5 and, after taking a quick look at the programme and the names of the important thinkers standing out on it, one could have expected to find a crowded audience room. Actually that was not quite the case. What I could afford to follow and am going to write about here is only the first day of the conference. The debate started right on time, after a short introduction given by Gabriele Galluzzo, both organizer of the conference and member of the scientific board. I would ac- tually like to underline the word debate: each speech (about 40 minutes) was immediately followed by a short discussion of the issues introduced by the proponent. Unfortunately, de- spite of the accurate and punctual speeches, the little time dedicated to each is what most penalized the conference, in my opinion: this inevitably obliged both the speakers and the audience to be plunged in medias res, without standing too much on ceremonies. I take this to be ‘penalizing’, considering the debate on universals is a very wide one and composed by an incredibly great number of positions which can sometimes start from oppo- site sides and some other times depart at some specific middle point of one single theory of properties and relations. Moreover, most (if not all) of them entail a certain number of other metaphysical themes from which the specific problematics of universals cannot be cut off. -

Philosophy.Pdf

Philosophy 1 PHIL:1401 Matters of Life and Death 3 s.h. Contemporary ethical controversies with life and death Philosophy implications; topics may include famine, brain death, animal ethics, abortion, torture, terrorism, capital punishment. GE: Chair Values and Culture. • David Cunning PHIL:1636 Principles of Reasoning: Argument and Undergraduate major: philosophy (B.A.) Debate 3 s.h. Undergraduate minor: philosophy Critical thinking and its application to arguments and debates. Graduate degrees: M.A. in philosophy; Ph.D. in philosophy GE: Quantitative or Formal Reasoning. Faculty: https://clas.uiowa.edu/philosophy/people/faculty PHIL:1861 Introduction to Philosophy 3 s.h. Website: https://clas.uiowa.edu/philosophy/ Varied topics; may include personal identity, existence of The Department of Philosophy offers programs of study for God, philosophical skepticism, nature of mind and reality, undergraduate and graduate students. A major in philosophy time travel, and the good life; readings, films. GE: Values and develops abilities useful for careers in many fields and for any Culture. situation requiring clear, systematic thinking. PHIL:1902 Philosophy Lab: The Meaning of Life 1 s.h. Further exploration of PHIL:1033 course material with the The department also administers the interdisciplinary professor in a smaller group. undergraduate major in ethics and public policy, which it offers jointly with the Department of Economics and the PHIL:1904 Philosophy Lab: Liberty and the Pursuit of Department of Sociology and Criminology; see Ethics and Happiness 1 s.h. Public Policy in the Catalog. Further exploration of PHIL:1034 course material with the professor in a smaller group. Programs PHIL:1950 Philosophy Club 1-3 s.h. -

Philosophy 305 a Early Medieval Philosophy (4Th to the 12Th Century CE)

1 Philosophy 305 A Early Medieval Philosophy (4th to the 12th Century CE) This course begins with a brief presentation of the philosophies of Plato, Aristotle and Plotinus insofar as these were influential on medieval philosophical thought. It then considers major thinkers in the Christian traditions from the 4th to the 12th century CE, and includes a brief introduction to major Islamic and Jewish philosophers within that time period insofar as their speculations were influential on medieval Christian philosophy. Instructor: E-H. W. Kluge Office: CLE B313 Phone: (250)721-7519 e-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Mondays and Thursdays 10:00am - 11:20am Text: Arthur Hyman, James J. Walsh, & Thomas Williams, eds. Philosophy in the Middle Ages (3rd ed.) Cambridge, MA: Hackett. Formal Course Requirements and Grading Procedures Grades will be based on two mid-terms and a final examination. The mid-term examinations are fifty minutes long and the final examination is three hours in length. The mid-term examinations are each worth 20% of the course grade; the final examination is worth 60%. Students who have taken (and received a grade for) both mid-term examinations have the option of having the final examination count for 100% of their course grade. The mid-term examinations cover only the material that has not been tested before in the semester; the final examination is cumulative and covers all of the material dealt with in the course. Students are encouraged to discuss their mid- term examination with the instructor. Significant dates: - Mid-term examination #1: app. October 1 - Mid-term examination #2: app. -

Predication and the Problem of Universals Catherine Legg

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato Philosophical Papers Vol. 30, No. 2 (July 2001): 117-143 Predication and the Problem of Universals Catherine Legg Abstract: This paper contrasts the scholastic realists of David Armstrong and Charles Peirce. It is argued that the so-called 'problem of universals' is not a problem in pure ontology (concerning whether universals exist) as Armstrong construes it to be. Rather, it extends to issues concerning which predicates should be applied where, issues which Armstrong sets aside under the label of 'semantics', and which from a Peircean perspective encompass even the fundamentals of scientific methodology. It is argued that Peir ce's scholastic realism not only presents a more nuanced ontology (distinguishing the existent front the real) but also provides more of a sense of why realism should be a position worth fighting for. ... a realist is simply one who knows no more recondite reality than that which is represented in a true representation. C.S. Peirce Like many other philosophical problems, the grandly-named 'Problem of Universals' is difficult to define without begging the question that it raises. Laurence Goldstein, however, provides a helpful hands-off denotation of the problem by noting that it proceeds from what he calls The Trivial Obseruation:2 The observation is the seemingly incontrovertible claim that, 'sometimes some things have something in common'. The 1 Philosophical Writings of Peirce, ed. Justus Buehler (New York: Dover Publications, 1955), 248. 2 Laurence Goldstein, 'Scientific Scotism – The Emperor's New Trousers or Has Armstrong Made Some Real Strides?', Australasian Journal of Philosophy, vol 61, No. -

Introduction

Introduction At least four assumptions appear to be part of the common ground of inter pretation among scholars of Ockham. The first can be described as a kind of general methodological presupposition, in that it has become standard to explore the Franciscan as a potential contributor to current philosophical debates, such as the issue of externalism in the philosophy of language and in the philosophy of mind.1 The view that medieval philosophers – or at least, Ockham – are of interest only to historians and theologians does not enjoy great popularity, especially not among philosophers working in the tradition of analytic philosophy.2 Second, Ockham is usually labelled a nominalist. While nominalism is not a single unified position,3 Ockham can be called a nominalist insofar as he sub scribes to the view that there are only particular things in this world: he admits only of two kinds of things in his ontology, namely particular substances (Socrates, this apple) and particularized qualities (the wisdom of Socrates, the redness of this apple).4 It would perhaps be more fitting to call Ockham’s posi tion ‘particularistic’. He thereby takes a conceptual stance on the problem of universals.5 According to Ockham, universals are nothing but concepts exist ing in the intellect. There is nothing universal ‘out there’ in the world. That a concept such as whale or wisdom is universal means that whale is semantically 1 See for instance Peter King, ‘Rethinking Representation in the Middle Ages’, in H. Lagerlund (ed.), Representation and Objects of Thought in Medieval Philosophy, Hampshire, 2007; Calvin Normore, ‘Burge, Descartes and Us’, in M. -

Universals.Pdf

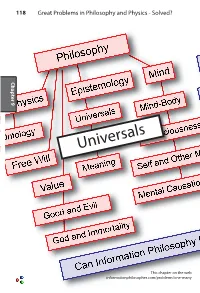

118 Great Problems in Philosophy and Physics - Solved? Chapter 9 Chapter Universals This chapter on the web informationphilosopher.com/problems/one-many Universals 119 Universals A “universal” in metaphysics is a property or attribute that is shared by many particular objects (or concepts). It has a subtle relationship to the problem of the one and the many. It is also the question of ontology.1 What exists in the world? Ontology is intimately connected with epistemology - how can we know what exists in the world? Knowledge about objects consists in describing the objects with properties and attributes, including their relations to other objects. Rarely are individual properties unique to an individual object. Although a “bundle of properties” may uniquely charac- 9 Chapter terize a particular individual, most properties are shared with many individuals. The “problem of universals” is the existential status of a given shared property. Does the one universal property exist apart from the many instances in particular objects? Plato thought it does. Aristotle thought it does not. Consider the property having the color red. Is there an abstract concept of redness or “being red?” Granted the idea of a concept of redness, in what way and where in particular does it exist? Nomi- nalists (sometimes called anti-realists) say that it exists only in the particular instances, and that redness is the name of this property. Conceptualists say that the concept of redness exists only in the minds of those persons who have grasped the concept of redness. They might exclude color-blind persons who cannot perceive red. -

William Ockham and Trope Nominalism

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department Classics and Religious Studies 1998 William Ockham and Trope Nominalism Stephen E. Lahey University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub Part of the Classics Commons Lahey, Stephen E., "William Ockham and Trope Nominalism" (1998). Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department. 85. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub/85 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. William Ockhsun and Trope Nominalism Can we take a medieval metaphysician out of his scholastic robes and force him into a metaphysical apparatus as seemingly foreign to him as a tuxedo might be? I believe that the terminological and conceptual differences that appear to prevent this can be overcome in many cases, and that one case most amenable to this project is the medieval problem of universals. After all, the problem for the medieval is, at base, the same as it is for contemporary philosophers, as for Plato: How do we account, ontologically, for many tokens of the same type? If one object has the property x and another, distinct object has the "same" property x, how to explain the apparent "samenessw of the property x? Is x one property or two? I will argue that William Ockharn's ontology, when considered in light of some contemporary philosophical thought, is remarkably fresh and vital, able seriously to be con- sidered as a tenable position, so long as we are clear about what Ockham is saying. -

P515 (§ 29794) Fall 2009 History of the Problem of Universals in the Middle Ages

P401 (§ 11962)/P515 (§ 29794) Fall 2009 History of the Problem of Universals in the Middle Ages Office Hours: E-mail: Title of the course: History of the Problem of Universals in the Middle Ages. This course is a combined undergraduate/graduate course, being offered under two simultaneous numbers: P401 for the undergraduate graduate version and P515 for the graduate version. The fact that we have two “instances” of what is in effect exactly the same course is perhaps an illustration of the very problem of universals that is the topic of this course. (I’ll say more about what that problem is in a moment.) But it’s not really exactly the same course. I will be expecting an appropriately more ambitious term-papers and examination answers from those of you taking this course under the graduate number. Handouts: (1) Syllabus Lectures: 2:30–3:45 PM Mondays & Wednesdays. Format: Lecture with some questions. Required Texts: Paul Vincent Spade, Five Texts on the Mediaeval Problem of Universals: Porphyry, Boethius, Abelard, Duns Scotus, Ockham, (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1994). Paul Vincent Spade, History of the Problem of Universals in the Middle Ages: Notes and Texts. A packet of materials containing additional notes on the translations in Five Texts, together with some further translations. It comes to 191 pages, and is available from Mr. Copy, 501 E. 10th St. (= 10th & Dunn) (334- 2679). ($29.90 plus tax.) 2 Bring these first two items to class with you regularly; I will be frequently referring to particular passages in them. Thomas Aquinas, On Being and Essence, Armand Maurer, tr. -

Predication and the Problem of Universals Catherine Legg

Philosophical Papers Vol. 30, No. 2 (July 2001): 117-143 Predication and the Problem of Universals Catherine Legg Abstract: This paper contrasts the scholastic realists of David Armstrong and Charles Peirce. It is argued that the so-called 'problem of universals' is not a problem in pure ontology (concerning whether universals exist) as Armstrong construes it to be. Rather, it extends to issues concerning which predicates should be applied where, issues which Armstrong sets aside under the label of 'semantics', and which from a Peircean perspective encompass even the fundamentals of scientific methodology. It is argued that Peir ce's scholastic realism not only presents a more nuanced ontology (distinguishing the existent front the real) but also provides more of a sense of why realism should be a position worth fighting for. ... a realist is simply one who knows no more recondite reality than that which is represented in a true representation. C.S. Peirce Like many other philosophical problems, the grandly-named 'Problem of Universals' is difficult to define without begging the question that it raises. Laurence Goldstein, however, provides a helpful hands-off denotation of the problem by noting that it proceeds from what he calls The Trivial Obseruation:2 The observation is the seemingly incontrovertible claim that, 'sometimes some things have something in common'. The 1 Philosophical Writings of Peirce, ed. Justus Buehler (New York: Dover Publications, 1955), 248. 2 Laurence Goldstein, 'Scientific Scotism – The Emperor's New Trousers or Has Armstrong Made Some Real Strides?', Australasian Journal of Philosophy, vol 61, No. 1 (March 1983), 40.