Who Killed Emmett Till?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viewers Recognize the Youth and Wholesomeness of Her Son Unsettle These

© 2010 KATE L. FLACH ALL RIGHTS RESERVED MAMIE TILL AND JULIA: BLACK WOMEN’S JOURNEY FROM REAL TO REALISTIC IN 1950S AND 60S TV A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of the University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, History Kate L. Flach December, 2010 MAMIE TILL AND JULIA: BLACK WOMEN’S JOURNEY FROM REAL TO REALISTIC IN 1950S AND 60S Kate L. Flach Thesis Approved: Accepted: ________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Tracey Jean Boisseau Dr. Chand Midha ________________________________ _________________________________ Co-Advisor Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Zachary Williams Dr. George R. Newkome ________________________________ _________________________________ Department Chair Date Dr. Michael Sheng ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................1 II. FROM REAL IMAGES TO REEL EXPOSURE ......................................................5 III. WATCH AND LEARN: ESTABLISHING BLACK MIDDLE CLASS-NESS THROUGH MEDIA ................................................................................................17 IV. COVERING POST-WAR MOTHERHOOD ON TELEVISION ...........................26 V. INTERUPTING I LOVE LUCY FOR THIS? The Televised Emmett Till Trial ..............34 VI. CROSSING ALL Ts AND DOTTING LOWER CASE Js ......................................41 VII. CONCLUSION:“Okay, she can be the mother…” julia, November 26, -

|||GET||| Writing to Save a Life the Louis Till File 1St Edition

WRITING TO SAVE A LIFE THE LOUIS TILL FILE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE John Edgar Wideman | 9781501147289 | | | | | Louis Till Just wow! Everybody knows the tragic story of Emmett Till, but I never really thought of his father before I began reading this book. It seemed to this reader Wideman leveraged the story of Emmett Till and his father Louis to tell his own story. Help carry the weight of hard years spent behind bars. Though we certainly know how. Categories : births deaths 20th-century executions by the United States military 20th-century executions of American people African-American military personnel American army personnel of World War II American male criminals American people convicted of murder American people convicted of rape American people executed abroad Executed African-American people Executed people from Missouri Murder in Italy People executed by the United States military by hanging People convicted of murder by the United States military People executed for murder People from New Madrid, Missouri United States Army soldiers. This one was not an easy read, not because Writing to Save a Life The Louis Till File 1st edition the subject matter, but because of the meandering way it seemed to me to read. As apparently back then the sins of the fathers were visited upon their children, the federal case was never pursued. I stuck with it because I have a ton Writing to Save a Life The Louis Till File 1st edition respect for John Edgar Wideman and loved many of his books. On June 27,near the Italian town of Civitavecchia, where American soldiers were camped nearby, sirens sounded a false alarm, gunfire erupted as searchlights scanned the dark night sky. -

Behold the Corpse: Violent Images and the Case of Emmett Till

Behold the Corpse: Violent Images and the Case of Emmett Till Harold, Christine. DeLuca, Kevin Michael. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, Volume 8, Number 2, Summer 2005, pp. 263-286 (Article) Published by Michigan State University Press DOI: 10.1353/rap.2005.0075 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/rap/summary/v008/8.2harold.html Access provided by Penn State Univ Libraries (18 Mar 2013 10:52 GMT) BEHOLD THE CORPSE: VIOLENT IMAGES AND THE CASE OF EMMETT TILL CHRISTINE HAROLD AND KEVIN MICHAEL DELUCA The widely disseminated image of Emmett Till’s mutilated corpse rhetorically transformed the lynched black body from a symbol of unmitigated white power to one illustrating the ugliness of racial violence and the aggregate power of the black community. This reconfiguration was, in part, an effect of the black community’s embracing and foregrounding Till’s abject body as a collective “souvenir” rather than allowing it to be safely exiled from public life. We do not know what the body can do. Spinoza Society is concerned to tame the Photograph, to temper the madness which keeps threatening to explode in the face of whoever looks at it. Roland Barthes If the men who killed Emmett Till had known his body would free a people, they would have let him live. Reverend Jesse Jackson Sr. “ had to get through this. There would be no second chance to get through Ithis. I noticed that none of Emmett’s body was scarred. It was bloated, the skin was loose, but there were no scars, no signs of violence anywhere. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 154 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, AUGUST 1, 2008 No. 130 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. environmental group based in the Mad families that their interests are impor- The Chaplain, the Reverend Daniel P. River Valley of Vermont. Formed in tant enough for this Congress to stay Coughlin, offered the following prayer: the fall of 2007 by three local environ- here and lower gas prices. Is God in the motion or in the static? mentalists, Carbon Shredders dedicates In conclusion, God bless our troops, Is God in the problem or in the re- its time to curbing local energy con- and we will never forget September the solve? sumption, helping Vermonters lower 11th. Godspeed for the future careers to Is God in the activity or in the rest? their energy costs, and working to- Second District staff members, Chirag Is God in the noise or in the silence? wards a clean energy future. The group Shah and Kori Lorick. Wherever You are, Lord God, be in challenges participants to alter their f our midst, both now and forever. lifestyles in ways consistent with the Amen. goal of reducing energy consumption. COMMEMORATING THE MIN- In March, three Vermont towns f NEAPOLIS I–35W BRIDGE COL- passed resolutions introduced by Car- LAPSE THE JOURNAL bon Shredders that call on residents (Mr. ELLISON asked and was given The SPEAKER. The Chair has exam- and businesses to reduce their carbon footprint by 10 percent by 2010. -

Emmett Till and the Modernization of Law Enforcement in Mississippi

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of San Diego San Diego Law Review Volume 46 | Issue 2 Article 6 5-1-2009 The ioleV nt Bear It Away: Emmett iT ll and the Modernization of Law Enforcement in Mississippi Anders Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/sdlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Anders Walker, The Violent Bear It Away: Emmett iT ll and the Modernization of Law Enforcement in Mississippi, 46 San Diego L. Rev. 459 (2009). Available at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/sdlr/vol46/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in San Diego Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WALKER_FINAL_ARTICLE[1] 7/8/2009 9:00:38 AM The Violent Bear It Away: Emmett Till and the Modernization of Law Enforcement in Mississippi ANDERS WALKER* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 460 II. LESSONS FROM THE PAST ................................................................................... 464 III. RESISTING “NULLIFICATION” ............................................................................. 468 IV. M IS FOR MISSISSIPPI AND MURDER.................................................................... 473 V. CENTRALIZING LAW ENFORCEMENT ................................................................. -

Mississippi Community Colleges Serve, Prepare, and Support Mississippians

Mississippi Community Colleges Serve, Prepare, and Support Mississippians January 2020 1 January 2020 Prepared by NSPARC / A unit of Mississippi State University 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary...............................................................................................................................1 Introduction.......................................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Institutional Profile...............................................................................................................................4 Student Enrollment...............................................................................................................................6 Community College Graduates.............................................................................................................9 Employment and Earnings Outcomes of Graduates..........................................................................11 Impact on the State Economy.............................................................................................................13 Appendix A: Workforce Training.........................................................................................................15 Appendix B: Degrees Awarded............................................................................................................16 -

The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till

Presents THE UNTOLD STORY OF EMMETT LOUIS TILL A Till Freedom Come Production A Film by Keith Beauchamp CAST AND CREW FEATURING Mamie Till-Mobley Reverend Wheeler Parker Simeon Wright Ruthie Mae Crawford Reverend Al Sharpton Roosevelt Crawford John Crawford Willie Reed Mary Johnson Dan Wakefield Willie Nesley Henry Lee Loggins PRODUCER-DIRECTOR Keith A. Beauchamp CO-PRODUCER Yolande Geralds EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Edgar E. Beauchamp Ceola J. Beauchamp Steven J. Laitmon Ali Bey Jacki Ochs ASSOCIATE PRODUCERS Ronnique Hawkins Steven Beer CAMERAS Rondrick Cowins Scott Marshall Sikay Tang EDITOR David Dessel, Metaphor Pictures LLC ORIGINAL SCORE Jim Papoulis SOUND EDIT & MIX Margret Crimmins Greg Smith Dog Bark Sound ARCHIVAL FOOTAGE A/P Wide World Photos CBS News Archives Fox Movietone News Jet Magazine/Johnson Library of Congress Publications Mississippi Department of Archives and History Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries UCLA Films and Television Archives VOCALS Odetta courtesy of Doug Yeager Productions LTD Maurice Laucher Caryl Papoulis MUSIC “The Death of Emmett Till” performed by Bob Dylan appears courtesy of Columbia Records/ Special Rider Music (SESAC) THE UNTOLD STORY OF EMMETT LOUIS TILL production notes – DRAFT, p. 2 of 8 ABOUT THE FILM THE UNTOLD STORY OF EMMETT LOUIS TILL is a documentary investigating the murder and subsequent injustice surrounding Emmett Louis Till’s death. Many consider this case to be the true catalyst for the American Civil Rights Movement. In August 1955, Mamie Till-Mobley of Chicago sent her only child, 14-year old Emmett Louis Till, to visit relatives in the Mississippi Delta. Little did she know that 8 days later, Emmett would be abducted from his Great-Uncle’s home, brutally beaten and murdered for one of the oldest Southern taboos: addressing a white woman in public. -

Race, Genre and Commodification in the Detective Fiction of Chester Himes

Pulping the Black Atlantic: Race, Genre and Commodification in the Detective Fiction of Chester Himes A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of PhD in the Faculty of Humanities 2010 William Turner School of Arts, Histories and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………... 3 Declaration/Copyright……………………………………………………………. 4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………… 5 Introduction: Chester Himes’s Harlem and the Politics of Potboiling…………………………. 6 Part One: Noir Atlantic 1. ‘I felt like a man without a country.’: Himes’s American Dilemma …………………………………………………….41 2. ‘What else can a black writer write about but being black?’: Himes’s Paradoxical Exile……………………………………………………….58 3. ‘Naturally, the Negro.’: Himes and the Noir Formula……………………………………………………..77 Part Two: ‘The crossroads of Black America.’ 4. ‘Stick in a hand and draw back a nub.’: The Aesthetics of Urban Pathology in Himes’s Harlem……………………….... 96 5. ‘If trouble was money…’: Harlem’s Hustling Ethic and the Politics of Commodification…………………116 6. ‘That’s how you got to look like Frankenstein’s Monster.’: Divided Detectives, Authorial Schisms………………………………………... 135 Part Three: Pulping the Black Aesthetic 7. ‘I became famous in a petit kind of way.’: American (Mis)recognition…………………………………………………….. 154 8. ‘That don’t make sense.’: Writing a Revolution Without a Plot…………………………………………… 175 Conclusion: Of Pulp and Protest……………………………………………………………...194 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………. 201 Word count: 85,936 3 Abstract The career path of African American novelist Chester Himes is often characterised as a u-turn. Himes grew to recognition in the 1940s as a writer of the Popular Front, and a pioneer of the era’s black ‘protest’ fiction. However, after falling out of domestic favour in the early 1950s, Himes emigrated to Paris, where he would go on to publish eight Harlem-set detective novels (1957-1969) for Gallimard’s La Série Noire. -

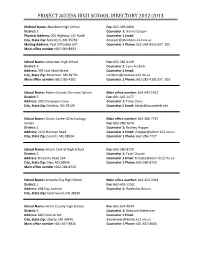

Project Access High School Directory 2012-2013

PROJECT ACCESS HIGH SCHOOL DIRECTORY 2012-2013 0School Name: Aberdeen High School Fax: 662-369-6004 District: 2 Counselor 1: Donna Cooper Physical Address: 205 Highway 145 North Counselor 1 Email: City, State Zip: Aberdeen, MS 39730 [email protected] Mailing Address: Post OfficeBox 607 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-369-8933 EXT. 205 Main office number: 662-369-8933 School Name: Ackerman High School Fax: 662-285-4149 District: 4 Counselor 1: Lynn Scribner Address: 393 East Main Street Counselor 1 Email: City, State Zip: Ackerman, MS 39735 [email protected] Main office number: 662-285-4101 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-285-4101 EXT. 103 School Name: Adams County Chrisitian School Main office number: 601-442-1422 District: 5 Fax: 601-442-1477 Address: 300 Chinquapin Lane Counselor 1: Tracy Davis City, State Zip: Natchez, MS 39120 Counselor 1 Email: [email protected] School Name: Alcorn Career &Technology Main office number: 662-286-7727 Center Fax: 662-286-5674 District: 2 Counselor 1: Rodney Hopper Address: 2101 Norman Road Counselor 1 Email: [email protected] City, State Zip: Corinth, MS 38834 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-286-7727 School Name: Alcorn Central High School Fax: 662-286-8720 District: 2 Counselor 1: Tazel Choate Address: 8 County Road 254 Counselor 1 Email: [email protected] City, State Zip: Glen, MS 38846 Counselor 1 Phone: 662-286-8720 Main office number: 662-286-8720 School Name: Amanda Elzy High School Main office number: 662-453-3394 District: 1 Fax: 662-453-1258 Address: 604 Elzy Avenue Counselor 1: -

Civil Rights Historical Investigations

CIVIL RIGHTS HISTORICAL INVESTIGATIONS A FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES PUBLICATION CIVIL RIGHTS HISTORICAL INVESTIGATIONS A FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES PUBLICATION Facing History and Ourselves is an international educational and professional development orga- nization whose mission is to engage students of diverse backgrounds in an examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism in order to promote the development of a more humane and informed citizenry. By studying the historical development of the Holocaust and other examples of genocide, students make the essential connection between history and the moral choices they confront in their own lives. For more information about Facing History and Ourselves, please visit our website at www.facinghistory.org. Copyright © 2010 by Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. Facing History and Ourselves® is a trademark registered in the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office. Facing History and Ourselves Headquarters 16 Hurd Road Brookline, MA 02445-6919 ABOUT FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES Facing History and Ourselves is a nonprofit educational organization whose mission is to engage students of diverse backgrounds in an examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism in order to promote a more humane and informed citizenry. As the name Facing History and Ourselves implies, the organization helps teachers and their students make the essential connections between history and the moral choices they confront in their own lives, and offers a framework and a vocabu- lary -

The Emmett Till Lynching and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Reporting the movement in black and white: the Emmett iT ll lynching and the Montgomery bus boycott John Craig Flournoy Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Flournoy, John Craig, "Reporting the movement in black and white: the Emmett iT ll lynching and the Montgomery bus boycott" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3023. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3023 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REPORTING THE MOVEMENT IN BLACK AND WHITE: THE EMMETT TILL LYNCHING AND THE MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Manship School of Mass Communication By Craig Flournoy B.A., University of New Orleans, 1975 M.A., Southern Methodist University, 1986 August 2003 Acknowledgements The researcher would like to thank several members of the faculty of the Manship School of Mass Communication at Louisiana State University for their help and inspiration in preparing this dissertation. Dr. Ralph Izard, who chaired the researcher’s dissertation committee, has been steady, tough and wise. In other words, Dr. -

Chapter 1: Background & Analysis

CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND & ANALYSIS G ENERAL F EATURES Location Greenwood is the county seat of Leflore County, Mississippi and is located at the eastern edge of the Mississippi Delta, approximately 96 miles north of Jackson, Mississippi and 130 miles south of Memphis, Tennessee. Natural Features The city has a total area of 9.5 square miles, of which 9.2 square miles is land and 0.3 square miles of it is water (3.15%). Greenwood is located where the Tallahatchie and Yalobusha rivers join to form the Yazoo River. In fact, Greenwood is one of the few places in the world where you can stand between two rivers, the Yazoo and the Tallahatchie Rivers, flowing in the opposite direction. The flood plain of the Mississippi River has long been an area rich in vegetation and wildlife, feeding off the Mississippi and its numerous tributaries. Long before Europeans migrated to America, the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indian nations settled in the Delta's marsh and swampland. In 1830, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was signed by Choctaw Chief Greenwood Leflore, opening the swampland to European settlers. Picture: Greenwood's Grand Boulevard once named one of America's ten most beautiful streets by the U.S. Chambers of Commerce and the Garden Clubs of America. History The first settlement on the banks of the Yazoo River was a trading post founded by John Williams in 1830 and known as Williams Landing. The settlement quickly blossomed, and in 1844 was incorporated as “Greenwood,” named after Chief Greenwood Leflore. Growing into a strong cotton market, the key to the city’s success was based on its strategic location in the heart of the Delta, on the easternmost point of the alluvial plain and astride the Tallahatchie River and the Yazoo River.