Pdf> [Accessed 9 May 2012]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2021 2019 Issueissue No.No

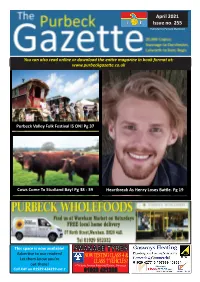

NovemberApril 2021 2019 IssueIssue no.no. 255238 Published by Purbeck Media Ltd FREE WHEREYou can DELIVERED also read. POSTAL online SUBSCRIPTION or download AVAILABLE the entire at: www.purbeckgazette.co.uk/catalogue.aspx magazine in book format at: Magazine Archive at: www.purbeckgazette.co.uk PurbeckPurbeckHelp Valley Christmas Save FolkRex TheChallenge!Festival Brave. IS PgPgON! 1223 Pg - 3737 Our Flag Is Now Official! Pg 16 CowsBanish Come Those To WinterStudland Blues! Bay! PgPg 2438 -- 3539 HeartbreakOtter Deaths As Henry On The Loses Increase. Battle. Pg Pg 37 19 SWANAGE & PURBECK TAXI SWANAGE TYRES This spaceCall Martin is now Williams available! Advertise to our readers! on 07969 927424 NOW TESTING CLASS 4 & Let them know you’re QUAY CARS TAXI CLASS 7 VEHICLES! 4-7 seater. Airportsout there! - Docks - Local Tours 6 Victoria Avenue Industrial Estate, Swanage CallCall: KAY07788 on 01929 2345424239 ext.145 01929 421398 2 The Purbeck Gazette Editor’s note... The Purbeck Gazette is elcome to the April 2021 edition of your Purbeck Gazette! delivered by: WFor the first time in our history we have not included one of our famous April Fools in this edition. Why? Our various correspondents had a We distribute 20,000 copies of the Purbeck Zoom meeting and couldn’t come up with anything Gazette every month to properties in Purbeck humourous - not because they are incapable or utilising Logiforce GPS-tracked delivery teams. unimaginative, but simply because this past year has not been a laughable matter, to be frank! Various ideas were mulled (Residents in blocks of flats, or who live up long driveways or in lesser over before the decision was made that we’d give this year a miss populated areas will not get a door-to-door delivery. -

Friday 13Th—Sunday 22Nd March 41St Lancaster Literature Festival Litfest 2020 Letter from the Chair

Friday 13th—Sunday 22nd March 41st Lancaster Literature Festival Litfest 2020 Letter from the Chair This year we celebrate the 41st Lancaster Literature Festival and we hope you will enjoy the programme we have to present to you. This year the festival will be running from the 13th March – 22nd March. We believe we have a programme which provides an excellent variety of events suitable for all ages. The festival will be launched on 13th March at the Priory and we welcome Professor Robert Barrett, Head of the Eden Project Learning to talk about the exciting plans for Eden North on Morecambe Bay. This is a fabulous opportunity to discover more about this project. We are delighted to bring to you two exhibitions during the festival which will be showcased at Lancaster Library. The first is called ‘Migrations’ and we are honoured to host this international exhibition in Lancaster which features the work of many artists from across the world exploring the subject of migration through illustrations. The second exhibition ‘In Pursuit of Peace and Hope’ has been created locally by young refugees covering three countries South Africa, Turkey and Uganda. The work has been led by Dr Melis Cin from Lancaster University. To bring the exhibitions to life we have our first Illustration Day featuring two illustrators. Illustration and the power of illustrations to tell compelling stories is something that Litfest wants to promote further in our programmes. We have an impressive array of authors and poets this year, beginning with best-selling Norwegian author Lars Mytting. We are also proud to showcase the work of eminent thinker A.C. -

Harrow House International College

HARROW HOUSE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE Beach Games London Excursion Tennis Coaching Oxford Excursion 2015 Swimming Pool and Durlston Residence Harrow House and Swanage Bay Education Building and Garden Harrow House Swanage occupies an elevated position in the centre of the town, enjoying splendid views of the surrounding Purbeck Hills, the sea and the Isle of Wight. The sandy beaches and the town's attractions are within 10 minutes’ walking distance. Harrow House is the only International College in Swanage Swanage and therefore our students are guaranteed integration with English people, their customs and the English way of life. Our Mission Statement We at Harrow House are dedicated to providing our students, employees and partners with the highest standards of learning and personal development in a fun and culturally diverse environment. With constant improvement of our programmes, facilities and services through continuous innovation and creativity, we are committed to being the Premier English Language, Education and Training Centre. Harrow House Together this creates a unique concept which we call ’The Harrow House Experience’. 25 18 13 17 24 14 16 5 21 26 12 15 3 4 23 2 11 6 20 22 1 10 19 9 7 8 34 33 2 Swanage Pier and Seafront Harrow House Students at the Beach Beach Games Swanage, the capital of the Isle of Purbeck and approximately 2.5 hours from London, is a popular seaside resort on the south coast of England, with long inviting expanses of sandy beaches, clear unpolluted water and breathtaking coastal scenery. The town provides a warm welcome to all visitors and retains an atmosphere of safety and tranquillity. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Wednesday Volume 689 24 February 2021 No. 179 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 24 February 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 897 24 FEBRUARY 2021 898 ThePresidentof COP26(AlokSharma):Wearedetermined House of Commons to build back better and greener as we recover from covid-19. The Prime Minister’s 10-point plan for a green Wednesday 24 February 2021 industrial revolution sets out the Government’s blueprint to grow the sunrise sector, support 250,000 green jobs and level up across the country. The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock Mark Menzies [V]: The north-west, as you are well PRAYERS aware, Mr Speaker,is the heart of the UK nuclear industry, including Westinghouse nuclear fuels in my constituency. [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] With the world increasingly focused on utilising low Virtual participation in proceedings commenced (Orders, carbon energy sources, what steps is my right hon. 4 June and 30 December 2020). Friend the President taking ahead of COP26 to promote [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] UK-based nuclear energy production satisfying our future energy needs and supporting countless high-skilled jobs Speaker’s Statement across the north-west? Mr Speaker: Her Majesty the Queen will, in less than Alok Sharma: My hon. Friend is absolutely right. one year from now, mark the 70th anniversary of her Nuclear power clearly has a part to play in our clean accession to the throne. -

Creative Writing on Place and Nature

Creative Writing on Place and Nature Jean Sprackland A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Published Work (Route 2) Department of English Manchester Metropolitan University 2016 i Abstract This PhD by Publication (Route 2) brings together a series of three books of which I am the sole author, and which share common ground in terms of theme and preoccupation. I seek to demonstrate how these three publications have contributed to the existing body of work in creative writing about place and nature, and specifically how they might be seen to address three key research questions. The submission includes my two most recent poetry collections, Tilt (2007) and Sleeping Keys (2013), both of which are characterised by an awareness of place and an acute attention to the natural world. These two collections explore two very different kinds of location: the poems in Tilt are mostly situated in the wide open spaces of the coast, whereas those in Sleeping Keys are largely located indoors, in the rooms of houses, occupied or abandoned. The third item in the submission is Strands: A Year of Discoveries on the Beach (2012), a book of essays or meditations which collectively describe a year’s walking on the wild estuarial beaches between Formby and Southport, charting the changing character of place through different weathers and seasons. This text might be classified as ‘creative non-fiction’ or ‘narrative non-fiction’ (neither of these terms is entirely uncontroversial or clearly defined). These three books have achieved a large and international readership. -

Dorset - South Coast Migration Special

Dorset - South Coast Migration Special Naturetrek Tour Report 12 - 14 October 2018 Great Egret Oak Rustic Lesser Yellowlegs Ruff Report and images by Simon Breeze Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Dorset - South Coast Migration Special Tour participants: Simon Breeze (Leader) with seven Naturetrek clients Summary The inaugural Dorset Coast autumn migration tour visited a suite of the county’s premier bird and wildlife locations in search of migration in action. From south-bound passerines and seabirds on passage, to incoming waders and wildfowl visiting our shores from northern climes, Dorset in autumn shows some of the very best in bird migration around UK shores. Despite high winds at the beginning of the tour from the tail of Storm Callum and some wet conditions the group managed to stay, for the most part, out of the brunt of the weather enabling us to go in search of a variety of rare, scarce and common migrant birds along with residents faithful to their autumnal foraging grounds. Day 1 Friday 12th October On a seasonally windy, overcast and mild afternoon the group checked in to the Morton’s House Hotel in Corfe Castle, where the castle and surrounding limestone clad village would be our surroundings for the weekend. Meeting in the sitting room Simon provided an introduction for tour ahead, including the sites to be visited, birds likely to be encountered and that we hoped to locate and a summary of the significance of Dorset’s geographical and geological locations and habitats. -

Interpretation Action Plan

INTERPRETATION ACTION PLAN March 2005 “We aspire to be the leading regional and national example of how achieving the conservation, understanding, enjoyment and sustainable use of the environment can also lead to social and economic development” (Dorset and East Devon Coast World Heritage Site Framework for Action) DORSET AND EAST DEVON COAST WORLD HERITAGE SITE JCWHS Interpretation Action Plan March 2005 1 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 3 2 CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................ 4 3 INTERPRETATION .................................................................................................................................... 7 4 JURASSIC COAST STORIES ....................................................................................................................... 9 5 THE ASPIRATION ....................................................................................................................................11 5.1 Site-wide projects ..........................................................................................................................11 5.2 Site-specific projects ......................................................................................................................16 6 MEANS OF DELIVERY..............................................................................................................................29 -

Beyond the Benchmark

Beyond the Benchmark Creative writing in higher education November 2013 Paul Munden Contents Section Page Foreword by Ian McMillan 4 Foreword from the Higher Education Academy 5 Acknowledgements 6 About the author 6 1. Introduction 7 1.1. Methodology 7 1.2. Statistics 8 1.3. Summary of other findings 8 1.4. Relevance and rewards 9 2. Programme structures 11 2.1. Staffing 11 2.2. Unique selling points 12 3. Recruitment and retention 14 3.1. Transition 15 3.2. The Creative Writing A-level 16 3.3. Study support 18 3.4. Satisfaction and retention 18 4. Teaching 20 4.1. The workshop 20 4.2. Size matters 21 4.3. Other strategies 21 4.4. Reading 23 4.5. Theory 24 4.6. Assessment 25 4.7. The worst offence 26 4.8. Teaching to teach 26 5. Research 28 5.1. Practice-based, practice-led 28 5.2. The financial imperative 29 5.3. Ethics 29 2 6. Employability 31 6.1. Professional development 31 6.2. Work placements 32 6.3. Publishing 32 6.4. Keeping track 33 7. Conclusions 34 7.1. The creative economy 35 7.2. Community value 36 7.3. Causes for concern 36 7.4 The next chapter 38 References 39 Appendix 41 3 Foreword by Ian McMillan I walk into Mad Geoff’s barber’s shop to get my hair cut. There’s a long queue snaking round the room and almost spilling out onto the pavement. People turn and look as I walk in and Geoff says, “We’re okay now: Ian’s here! We’ll all be writing poems soon!” I join in the laughter and of course I don’t get them all writing poems, although we do talk about poetry, and how it sometimes rhymes and sometimes doesn’t, and one man quotes Daffodils and one man gives us a scurrilous limerick about somebody from Leeds and I have a vision that one day Mad Geoff’s will be a branch of the world of creative writing and he’ll offer degrees and A-levels. -

HARROW HOUSE International College

2018 HARROW HOUSE International College English Language Courses for Young Learners, Juniors, Adults and Parents 5 9b 4 9a 8a 2 3 1 9f 6 8b 9g Welcome to Harrow House The complete English language experience Harrow House was founded in 1969 with the goal of providing an unrivalled English language experience. Regularly hosting students from as many as 40 different countries, we offer a unique combination of on-site facilities, College and Homestay accommodation in a safe, UNESCO seaside location. We at Harrow House are dedicated to providing students, employees and partners with the highest standards of learning and personal development in a fun and culturally diverse environment. With constant improvement of our courses, facilities and services through innovation and creativity, we are committed to offering the Premier English Language Experience. All this creates a unique concept that we call ‘The Harrow House Experience’. 2 Unrivalled on-site facilities 1 Education Department Building 5 Bayview Building includes includes • LookOut lounge including Wi-Fi, • Reception disco and social activities areas • Meeting room • Wessex room including Wi-Fi, TVs and • Academic office Wii games • IT office • Purbeck lecture hall, cinema, TV, piano 9c • Staff room • Restaurant • Staff resource room • Squash court, dance and yoga studio • 26 Classrooms with interactive • Fitness studio whiteboards and internet access on • Standard College bedrooms 9d 9e three floors 6 Studland Multipurpose Building • 24 computers with internet access in includes two -

Shoreline Makes It to the Top of the Empire State Building with Kay Solomon, Her Daughter and Granddaughter

AUTUMN 2014 WORLD WAR I AND II COMMEMORATIVE ISSUE FREE All the Fun Shoreline’s a Winner of the Fayre Page 3 Page 3 Photo Dorset Echo Family, Wartime and Growing up in Charmouth Page 22 Who’s Reading Charmouth Primary School Shoreline? Page 34 Page 4 Shoreline makes it to the top of the Empire State Building with Kay Solomon, her daughter and granddaughter Happy Days at the Charmouth Gardeners’ Show - Page 12 SHORELINE AUTUMN 2014 / ISSUE 26 1 Shoreline Autumn 2014 Award-Winning Hotel and Restaurant Four Luxury Suites, family friendly www.whitehousehotel.com 01297 560411 @charmouthhotel Nestled in the old town in Lyme Regis, we create delicious real ales in the traditional way using malted Fun, funky and barley, hops, yeast and water. The ever popular beers: Cobb, Lyme Gold, Town Mill Best, Black Ven and Revenge are available in pubs, shops and gorgeous gifts restaurants across the South West. Come in, watch us brew, taste our beers and have a pint or two. Drink in the atmosphere down at the Town Mill Brewery Tap. for everyone! For more information please visit www.townmillbrewery.com 01297 444354 [email protected] Next to Charmouth Stores (Nisa) The Street, Charmouth - Tel 01297 560304 If you don’t have any family to worry about, based on your home’s current value, while the ASK THE EXPERT then equity release may look like an attractive cost is based on its value at the end of the deal… proposition. Why struggle, or even deprive We are in our 60s and considering equity yourself of that holiday of a lifetime, when all But cost isn’t the only issue. -

Wordsworth, Memory, and Metaphor in Paul Farley's “Thorns”

“Never Some Easy Flashback” 6 DOI: 10.2478/abcsj-2013-0001 “NEVER SOME EASY FLASHBACK”: Wordsworth, Memory, and Metaphor in Paul Farley’s “Thorns” CHARLES ARMSTRONG University of Agder Abstract This paper provides a close reading of Paul Farley’s 160-line poem, “Thorns.” The poem is read in dialogue with William Wordsworth’s celebrated Romantic ballad “The Thorn.” Special attention is given to Farley’s treatment of memory and metaphor: It is shown how the first, exploratory part of the poem elaborates upon the interdependent nature of memory and metaphor, while the second part uses a more regulated form of imagery in its evocation of a generational memory linked to a particular place and time (the working-class Liverpool of the 1960s and 1970s). The tension between the two parts of the poem is reflected in the taut relationship between the poet and a confrontational alter ego. Wordsworth’s importance for Farley is shown to inhere not only in the Lake Poet’s use of personal memory, but also the close connection between his poetry and place, as well as a strongly self-reflective strain that results in an interminable process of self-determination. Farley’s independence as a poet also comes across, though, and is for instance in evidence in his desire to avoid the “booby trap” of too simple appropriation of the methods and motifs of his Romantic predecessor. Keywords: Paul Farley, William Wordsworth, contemporary poetry, Romantic poetry, literary influence, memory, metaphor, transcendence, class, political utopia The acclaimed, contemporary British poet Paul Farley was the writer in residence at The Wordsworth Trust in Grasmere between 2000 and 2002. -

Department of English Literature and Creative Writing Part I Module

Department of English Literature and Creative Writing Part I Module Booklet 2019-20 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Part I Reading lists ...................................................................................................................................... 2 ENGL100 English Literature Reading List ....................................................................................... 2 ENGL101 World Literature Reading List ......................................................................................... 3 General Information about the Reading Lists ................................................................................. 3 ENGL100: English Literature ................................................................................................................. 6 Course Outline ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Lecture Schedule ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Assessment................................................................................................................................................. 10 ENGL101: World Literature ................................................................................................................. 16